Who Put the Lock in Locktown?

The Kingwood Baptist Church and the Second Great Awakening

This article is based on an article published many years ago in “Friends Report,” the newsletter of the Friends of the Locktown Stone Church. I have added information and made some major corrections.

The Swamp Meeting House

In the village of Locktown, in Delaware Township, there is a handsome stone church constructed in 1819 in the federal style.

There had been a church building in this location as early as the mid-18th- century, but the place was not known as Locktown until 1856. Before then it was routinely designated “The Swamp Meeting House.” The ‘swamp’ was the Croton Plateau where water drains very poorly. Roads would go from or to the Swamp Meeting House, and might be known as, for instance, “the road from the Swamp Meeting House to Baptisttown” (now called the Locktown-Sergeantsville Road).

The Meeting House, or church, was one of two buildings used by the Kingwood Baptist congregation, which was founded in 1745. It was designated as the lower meeting house, as opposed to the original upper house in Baptistown (where else?).1

The Locktown stone church is a beautifully elegant building even though it was built to suit the needs of a Baptist congregation that frowned on extravagance or display. So how to explain this gorgeous door pediment? And the interior of the church is just as pleasing (though certainly not extravagant).

When the church was built, supervision of the project was given to Elisha Rittenhouse (1768-1846), who lived nearby on Old Mill Road in a lovely stone house, also in the federal style. He was clearly a man of taste. I sometimes wonder if Mr. Rittenhouse was also inspired by the character of the new pastor. On December 28, 1817, as one of the members of a church committee, Elisha Rittenhouse reported that “Mr. David Bateman answered the call to be pastor for one year.”2

Rev. David Bateman

Rev. David Bateman was born in Fairfield, Cumberland County on February 19, 1778. His father was Isaac Bateman, but I have not found his mother’s name. About the year 1800 David Bateman married widow Ruth Sheppard. They had three sons, Isaac, Daniel and David. Following the death of Ruth Sheppard Bateman in 1807, Rev. Bateman and his sons moved to Ohio.3 He later returned to New Jersey where he married second Sara McVaugn, and thirdly Mary Cox.4

How did the Kingwood Baptists learn of David Bateman? I wish I knew. Perhaps he reached out to them. Perhaps the family of his third wife, Mary Cox, introduced him to this part of New Jersey which was so far north of his home in Cumberland County. In any case, Bateman answered the call, and on April 5, 1818, the minutes stated “Mr. Bateman commenced ministerial service for one year.” He was hired again in January 1819, and agreed to preach in both the upper and lower meeting houses.

On January 2, 1819, the church decided to “build a new meetinghouse in the lower part of the Congregation near M. Wm Dilses.” In April, Daniel Rittenhouse deeded a small lot for the new meeting house and also for an expansion of the existing burying ground. On September 19, 1819, the minutes reported that pastor Bateman and his wife Mary were “received by letter.” This was apparently a formality since Bateman had been ministering to the congregation for five months. Then in October, the new meeting house was completed and used for the first time.

During these first two years of Rev. Bateman’s pastorate, a religious revival began. According to the Baptist chronicler, Rev. William Curtis:

. . . it “appeared to be general thruout the congregation, and continued more than two years. In which time more than one hundred were added to the church by baptism. Those that were baptised were of all ages, from the youth to the aged. After this the revival appeared to be over, until the latter part of the year 1822, at which time a revival commenced among the youth.”5

It is hard to say from this whether the revival was prompted by Rev. Bateman, or if he was simply a beneficiary of it. Revival or not, the congregation had trouble raising the funds to provide Rev. Bateman the kind of salary he expected. In October, the minutes noted that James Pyatt was to circulate a subscription to pay the pastor’s salary.

In 1821, Bateman asked for $300 per year and that was agreed to, but the next year it was not. The minutes are not clear about whether some other arrangement was reached, but the subject of subscriptions for raising a salary for the pastor reappeared over and over in the minute book. Still, the trustees could not complain about the job Rev. Bateman was doing. On Feb. 28, 1824, it was reported that there were 206 members in good standing.

Rev. Bateman was much loved by his congregation, so this parsimoniousness with his salary can only be attributed to the shortage of funds in the neighborhood.

The Second Great Awakening

The addition of so many new members and the religious fervor that prompted this seemed to trigger a re-evaluation of beliefs among the Baptists. There were two lines of thought, both of them intensified by the Second Great Awakening. One was traditional, Calvinistic, and known as the “American Particular Baptists.” They strongly believed in being separate from both the established church and from the state, and in being as decentralized as possible. They also held strongly to the idea of predestination, meaning that only those who were ‘called’ could belong to the church.

Another group felt the need for a more centralized organization, and more outreach in the form of missions to the American Indians and to natives of “foreign lands.” They also favored “protracted meetings,” evangelical pursuits, and support for the growing temperance movement. During the pastorship of Rev. Bateman, a balance was maintained between the two philosophies, even though a large part of the congregation preferred the Calvinistic approach.

The Death of Rev. Bateman

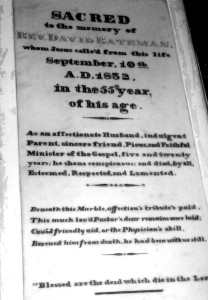

Rev. Bateman’s successful career as a preacher was halted when he retired in August 1832. He must have been ill, because he wrote his will on August 20, 1832. A month later, on September 10th, Rev. Bateman died at the age of 55, according to his gravestone. He was buried in the ground under the pulpit of the stone church,6 and his gravestone set into an altar table, with an inscription that showed the love he inspired in his congregants.

Sacred / to the memory of / Rev. David Bateman, / whom Jesus calle’d from this life / September, 1oth / A.D. 1832, / in the 55th year / of his age.

As an affectionate Husband, indulgent / Parent, sincere friend, Pious and Faithful / Minister of the Gospel, five and twenty / years; he shown conspicuous; and died, By all, / Esteemed, Respected and Lamented.

Beneath this Marble, affection’s tribute’s paid. / This much lov’d Pastor’s dear remains were laid; / Could friendly aid, or the Physician’s skill / Rescued him from death, he had been with us still. / “Blessed are the dead which die in the Lord.”

In his will, Rev. Bateman left very specific bequests to his wife Mary. He also left funds for “the maintenance and education” of his two daughters, who were unnamed, but presumably underage if they still needed an education. His bequest to wife Mary was unusually generous. Normally, a testator would declare that bequests to their widows would be cancelled if they should remarry. But in Mary Bateman’s case, she would still receive the sum of $1,000 to be put to interest for her support. Mary must have been well-educated herself, because Bateman also left her “all that part of my library which she had when I married her & to remain in her care.”

Bateman left to the church several books on religious topics “provided the Church will appoint a Libraryan to take charge of them. If not complyed with I give & bequeath them to the church at Sandy Ridge.” I suppose that was meant to be an incentive for the Kingwood Baptists to get themselves a “Libraryan.”

Bateman left his wearing apparel to sons Daniel S. and David Bateman, and his watch to son Moses Bateman. His property was to be sold and the proceeds divided between his sons Daniel and David. Apparently Moses had already been provided for. Witnesses to the will were James Pyatt, John Prall and John Sebold. His inventory was made on September 19th and 20th by Dr. James Pyatt and Alanson Rittenhouse, and totalled $1465.38, which was very satisfactory for a humble country pastor.

Rev. Bateman was succeeded first by William Curtis, who wrote the short history of the Baptist Church in 1833 that I quoted above. He left after six months, apparently being out of sympathy with the congregation. A local man, Thomas Risler, took up the preaching until a new pastor was recruited.

The year that Rev. Bateman died, a group of conservative Baptists from the eastern states met at Black Rock, Maryland to compose a general address in which they declared their resolve to withdraw fellowship from the liberal doctrines and practices of missions, education, tract societies, Bible societies and protracted meetings. They announced a “unitive consciousness of being the true, primitive, or old school Baptist church.” This sort of thing had happened long before when the Puritans broke away from the Church of England; it was the same sort of impulse, to get back to the “Primitive” or earliest church practices. The movement grew in strength, and found sympathizers in the Kingwood Church. It was in this context that a new pastor was recruited.

Rev. James W. Wigg

On August 30, 1834, “Brother James W. Wigg of New York” answered the call to replace the beloved Rev. Bateman. James Wigg was probably born in England around 1800. How he got to Hunterdon County is not known to me. He was welcomed to the church the previous June, when he was “received by letter,” which means he had previously been a member of a Baptist church in another location.

Around the time Elder Wigg was called to be pastor, divisions in the church had become pronounced. The situation was described by Thomas W. Lequear, in a history of the Hunterdon Baptists he wrote in 1887, published in the Hunterdon Republican:

Soon after Mr. Wigg, entered upon his pastorate, anti-mission and anti-temperance spirit crept into this church, leading the minds of many of the members from the adopted principles of the Philadelphia Association. This spirit was fostered and encouraged by the preaching of Elder Beebe, of the State of New York and by the circulation of a monthly publication, edited by him, called the “Signs of the Times.” This anti-mission, anti-temperance sentiment soon sought to control the church and in 1835, she resolved to withdraw from the Philadelphia Association, declaring they could no longer fellowship comfortably with it and soon after united with the Delaware River Baptist Association.

The Philadelphia Association of Baptist Churches, founded in 1707, was the over-reaching organization for Baptist Churches in the Mid-Atlantic region. It was sympathetic with ideas that sprung from the Second Great Awakening, reaching out for converts rather than waiting for them to come to the church, and promoting temperance through societies organized for that purpose. It favored missions, education, tract societies, Bible societies and protracted meetings.

The Delaware River Baptist Association mentioned above by Mr. Lequear consisted of the First Hopewell Church, the Second Hopewell Church (in Harbourton), the Southhampton Church (in Bucks County) and the Canton church in Camden County.

Rev. Wigg Gets Married

In the midst of all this controversy, Elder Wigg married Hulda Bray Rittenhouse on May 24, 1835. The marriage announcement in the Hunterdon Gazette read:

“Married, In Philadelphia, on the 24th ultimo, by the Rev. Thomas J. Kitts, the Rev. James W. Wigg of Kingwood, to Miss Huldah B. Rittenhouse, of Philadelphia.”

Huldah may have been living in Philadelphia at the time, but she was from a very old Hunterdon family. In fact, she was the granddaughter of Gen. Daniel Bray of Revolutionary War fame, and first cousin twice removed of the church builder, Elisha Rittenhouse. James and Huldah Wigg had one son, William B. Wigg, born December 1836, and possibly some daughters whose names I have not found.

Huldah Bray Rittenhouse was born April 9, 1808, the fifth of nine children, to Jonathan Rittenhouse and Delilah Bray. Huldah had been a member of the Kingwood Baptist Church since her admission on December 23, 1823. Prior to her marriage, from about 1828 on, Huldah’s parents were living on the farm of Charles Sergeant (now the Pauch farm)7, but Sergeant’s will ordered that the farm be sold to benefit his heirs. It was sold in 1833, but not to Jonathan Rittenhouse, so the family moved to the home farm of Huldah’s grandfather, Gen. Daniel Bray, in Kingwood.8

Conflict in the Kingwood Baptist Church

Rev. Wigg was in a difficult position, for although a little less than half the congregation favored the Philadelphia Association, the other half was strongly attached to the beliefs of the Delaware River Baptist Association. In 1836, Wigg was asked to write a circular letter to the churches of the Delaware River Association, which he did. But he made the mistake of stating that it was important to have a thorough acquaintance with the Scriptures. In other words, people should read the Bible for themselves. But the Association thought this was “truth unguarded,” and let Rev. Wigg know he had gone too far.

In January 1838, the church voted on whether to keep Brother Wigg on a pastor for the coming year. He won the vote by only a “small majority.” He was voted the same salary as in the past, $300, to be raised by subscription from “the neighbourhood of Centre bridge,” now Stockton. This is surprising, as Centre Bridge is some distance from the Swamp Meeting House. But it shows how wide an area the Kingwood Baptist Congregation covered.

Shortly after this, Rev. Wigg invited an evangelist preacher, Elder Ketchum, to attend a series of protracted meetings in December 1838 and January 1839. Protracted meetings were ecumenical in nature, probably having a bit of the flavor of revival meetings. For the conservative half of his congregation, this was the last straw, especially when the regular business meeting had to be cancelled twice in favor of the special meetings.

On February 2, 1839, the congregation met and passed a resolution

“that from this time on, Elder Wigg is dismissed from being pastor of this church in consequence of his departure from the doctrines and practices of this church, and his taking liberties with the church which she never gave him. Therefore from this day the church is considered destitute of a regular pastor, and Elder Wigg will not be permitted expected to preach in either meeting house or administer ordinances without permission from the church.”

It was also voted to have the keys of both church buildings “delivered into the hands of the deacons of said Church.”

The minutes went on to justify this extraordinary action, stating that Elder Wigg had been “advocating the principles and practices of the new school Baptists.” It was thought that the purpose of the protracted meeting with W. Ketchem was to gain time to get more converts and thereby a majority of church members to vote for the ‘New School’ policies.

After the vote was taken to dismiss Elder Wigg, one of the congregants rose to make more charges against him. Wigg refused to answer and “went immediately out of the house, and most of his party followed him.”9

At the next business meeting of the Church, on February 13, 1839, held “at the new meeting house” in Locktown, it was “Agreed to not receive any new members into this church without every member present being agreed to it” and also “Agreed that we hold Elder Wigg and all those that side with him in his departure from the doctrines and practice of this church in suspense.”

At a meeting held a week later on February 19th “at the Swamp meeting house,” more resolutions were made. It was “Agreed that the church alone do her own business and choose her trustees without the congregation agreeably to former practice.” Presumably, Rev. Wigg had instituted a more democratic voting procedure. Then this resolution:

Whereas James W. Wigg was on the 2nd Inst. dismissed from being pastor of this church for his departing from the doctrine and practice of this church &c and Whereas he is still persisting in his course in opposition to the church and denying her authority therefore agreed that he be excluded from all the privileges of the church. so from this day he is no more a member thereof. br’s [brothers] Mires & Sheppard to carry him the notice.

Following this was a list of names of church members who had “associated themselves” with Rev. Wigg. The minutes stated that since these members

have, associated themselves together in what they call a conference, contrary to the Government of this church. Therefore agreed that the above named persons and as many more as shall be found to have Joined the aforesaid conference be held in suspence [sic] or church censure until they return to the church and make acknowledgement for their departure and if they do not return they will be excluded.

Oddly enough, Rev. Wigg’s wife Huldah was not excluded from the church until eight months later, on October 26, 1839.

The church’s “librarian,” Deacon Samuel Dalrymple, was ordered to collect “the books belonging to the church and take them in his possession until they shall be wanted by a pastor of this church.” Brothers James and Benjamin Rittenhouse were appointed to go with him, lest, I suppose, there should be any trouble. This librarian held his position thanks to the will of David Bateman.

Locked Out

The next business meeting was set for March 2, 1839, a date to be remembered. It appears that Elder Wigg and his followers were not yet willing to accept their dismissal and showed it in a surprising way. As reported in the church minutes, on the date of the scheduled meeting,

The Church [the Old Schoolers] met agreeably to appointment at the meeting house in the township of Delaware. But the house being locked we could did not go in. Therefore we chose Samuel Dalrymple moderator and adjourned to br. George Dalrymples house.

Note the distinction between ‘could not go in’ and ‘did not go in.’

What is odd about this is that the Old Schoolers had voted to have the keys to both churches handed over to the church deacons. Apparently that hadn’t happened yet.

As for George Dalrymple’s house, that was the tavern next door later known as the Locktown Hotel. I do not know whether Samuel and George Dalrymple were related, but they were both among those opposed to the Wigg faction. Therefore, it was permissible to assemble at George Dalrymple’s house. It was also permissible because the Old Schoolers disapproved of the temperance movement. It is thought that they were already in the habit of visiting the tavern on Sabbath days, as a way to fortify themselves in the winter for the performance of a 3 or 4-hour-long sermon in an under-heated church.

This incident must have been one of the most exciting to occur in this very quiet village ever since construction of the church itself. Tradition says that one of the Old Schoolers placed another lock on the door to keep Rev. Wigg and his partisans out. Tradition also says that the tavern keeper, George ‘Derumple,’ had a sign made up for his tavern that featured three locks. By the time a post office was established in the village in 1856, the name Locktown had become standard usage.

Rev. Wigg and his followers had their own meeting the next month, which I will describe in the next installment. Meanwhile, here is an alphabetical list of church members who allied themselves with Rev. Wigg, as of 1841.10

Jacob Bieggle deceased 1843

Mary Bird died 1840

Elisha R. Bird

John Bird, died 1843

Jonathan Bird/Burd Dis Lett 1841

Moses Bird

Nancy Bird

Miss Sarah Bird

Susan Bird

Samuel Carcoff excluded 4/24/1841

Mrs. Mary Burd, w/o Jonathan, died 1840

Elizabeth Case (Dec’d 1843)

John Case

Mahlon Chamberlin

Elizabeth Dalrymple

Hannah Dalrymple

John Dalrymple

W. Peter and Mrs. Mary Ann Dalrymple, dism by lttr Mar 1842

Miss Sarah Dalrymple

Susan Dalrymple

Mrs Mary Dills (Dec’d 1840)

William Dills Died Oct 21, 1840

Mrs. Jane Dyke [sic], dism. by letter 1843

Catharine Everitt

Ezekiel Everitt Excluded Apr 1840, restored

Mary Everett

Dinah Fox

David Harden

Elizabeth Harden

Edward and Susan Haydock, dism. by letter 9 Mar 1844

W. S? B. Higgins, Dism. by Lttr 1841

Catharine Hoff

Jeremiah Hoff

Mr. Jonathan Hoff, died Apr 1845

Rachel Hoff [crossed out]

Catharine Hoffman excluded 1840; joined the old church

Elijah Hommel

Parmelia Howell

Sarah King

Elizabeth Lair

Sarah Larrison

Esther Lee

Francis R. Lee

Wm. Lee, dism. by letter 1845

Evan G. Mattison, excluded and restored

Hannah Manning

Hannah Mattison

Sarah McClary, excluded Feb 24, 1844

Westly McClary, excluded Mar 1842

Mrs Mary McPherson

Cornelius Mires, Dism. by Letter, 1843

Jesse Mires, Dism. by letter Mar 1842

Mr. Josiah Mires, Dsm. by Lttr 1841

Mrs. Mary Miers Dis Lett 1841

Mrs Sarah Mieers

Eliza Opdycke

Ann Pierson

Eli Pierce?, dism. by letter 1844

Daniel Pierson

James Pyatt

Mrs. Mary Ann Randolph, Dism. by letter Mar 1842

Stelle F. Randolph, excluded Mar 1842

Eremenah Risler

Daniel Rittenhouse

Daniel B. Rittenhouse

Racheal M. Rettenhouse

Mrs. Sarah Rettenhouse, Dis. by Letter 1841

Watson J. Rettenhouse Dis. L. 1841

Mrs. Wm. Robbins, died 1839

Mrs. Elizabeth Robbins, died May 1844

Daniel & Jane Roberson, dism. by letter 9 Mar 1844

Mordecai Roberts

Rebecca Roberts

Daniel Seabold (Suspended 1841; excluded Mar 1842; 1843; Feb 1844)

Phebe Seabold

Lydia Stout excluded 1840

Zebulon Stout excluded 184_?

Miss Susan Taylor, died 1840

Magdalene Tensman

Mrs. Catharine Thatcher, died 1843

Miss Eliz. Wagner, excluded Mar 1842

Elizabeth Warford

John Warick

Hugh Webster

Henry R. Wert excluded Apr 1841

Joseph West

Mrs. Pemely White, dism. by Lttr, 1841

Huldah B. Wiggs by letter 184_?; excluded Mar 1842

J. W. Wigg Dismissed by Letter 1841

Footnotes:

- For a basic history of the Kingwood Baptist Church, see Steven Zdepski, “Baptists in Kingwood, New Jersey.” Available at the Hunterdon Co. Historical Society and Hunterdon Co. Library. ↩

- Minutes of the Kingwood Baptist Church, as published in Phyllis D’Autrechy’s Some Records of Old Hunterdon, pp. 101-112. This first volume of the Minutes ends with 1823. ↩

- From History and Genealogy of Fenwick’s Colony, p. 206; this information came from the chapter on the Sheppard family and gave no further information about David Bateman. ↩

- I do not have definite proof of these marriages. They are not listed in Marriages Records of New Jersey, 1665-1800. ↩

- From “Century Old History of the Baptist Church at Kingwood,” by William Curtis, 1833, published by Hiram Deats, available at the Hunterdon Co. Historical Society. ↩

- In the 1980s, when the church was being restored by the Friends of the Locktown Stone Church, the floor was removed in order to replace the rotting joists. In the process, the grave of Rev. Bateman was discovered, right where it should be, directly underneath the pulpit. ↩

- Hunterdon Co. Deed Book 56 p.59. ↩

- On Nov. 18, 1840, the Bray farm was advertised in the Hunterdon Gazette as in possession of Jonathan Rittenhouse. ↩

- These quotes are taken from the original minute book of the Kingwood Baptists, at the Hunterdon Co. Historical Society. ↩

- “Minutes of the Missionary Particular Baptist Church of Kingwood,” Hunterdon Co. Historical Society, Ms #937. ↩

Frank Greenagel

February 21, 2014 @ 9:15 am

Wonderful detail! I had not heard that it was called the Swamp church.

Geoff Raike

February 21, 2014 @ 3:47 pm

Hi Marfy

I always enjoy reading your stories. In regards to having a hard time collecting fund for Rev. Bateman in 1821. The people may have been still recovering from the 1819 Economic crisis and depression. I’m sure everyone was tight on funds in a time when everything was bartered and money was scare. Just a thought.

Marfy Goodspeed

February 21, 2014 @ 4:32 pm

Good thought, Geoff. Yes, it was a slow recovery from the Panic of 1819. And cash was scarce in Hunterdon even in the best of times.

Kathie Kirkpatrick

February 22, 2014 @ 12:32 am

Once again, thank you for providing us with wonderful information.

Stephanie Stevens

February 22, 2014 @ 11:32 am

Hi Marfy,

Good story – I,too, had not heard of it as the “Swamp Church”. Your research is excellent

All the best,

Stephanie

Anne Philbrick

April 15, 2015 @ 7:04 pm

Great article! New Jersey marriage records indicate that David married Ruth on 31 Dec 1799 in Cumberland County. Massachusetts (based on newspapers) marriage records indicate that he married Mary in 1818 (prob March) in Millhill, New Jersey.