Be forewarned—this article is not for the squeamish.

As we watch the leaves die and the days get colder and shorter, it is natural to think about death. Why else would ghosts, skeletons and other creepy things be hanging from trees and cobwebs be draping our porches? Death is frightening. Celebrating Halloween is one way we cope with it.

Death is ever present. In the 19th century it was especially so. We can learn a lot about death and dying back then by looking at the Mortality Schedule for the 1850 census.

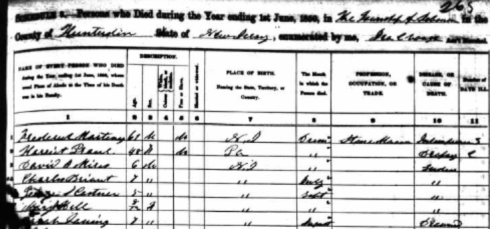

In 1850, the seventh U. S. Federal Census assembled a far more detailed listing of American residents and their characteristics than had ever been done before. Previously, the only information gathered was the name of the head of household, the number of members of the household, and their approximate ages. In 1850, for the first time, everyone was named, their exact ages were given, the place of their birth, their gender and race, their occupations and the value of their property. But the census went beyond all of that to study, in separate schedules, agriculture, industry, veterans and mortality.

Why a mortality schedule?

Most states did not have death registers in 1850, so there was no way to understand how many people were dying and why. The mortality schedule was an attempt to compensate for that. The official report for the 1870 mortality schedule stated that the information was gathered to “deduce the effect of the various conditions of life upon the duration of life.” In ante-bellum America, life was getting more complex, there was more urbanization, more immigration and more industrialization than ever before. The simple government of the 18th-century was no longer up to the challenge; more bureaucratization was needed, and census records were the foundation on which bureaucracies were built.

These are the questions that were asked for the mortality schedule: age at time of death, whether married or widowed, race, place of birth, occupation, month of death, cause of death, and duration of illness.

The deaths took place in the 12 months preceding June 1, 1850 (June 1, 1849 to May 31, 1850). But we can be certain that not everyone who died during that year got listed in the mortality schedule. The information was provided by the head of household, whose knowledge was not always accurate. And if the person who died was the head of household, then most likely that information was lost.

Causes of Death

It is clear from these lists that people did not understand illness very well. Some terms for illness were very vague, and in several cases, the cause of death was simply unknown—there were about 34 deaths from unknown causes. In later years, physicians were recruited to review the list of causes and “correct a defective classification.”1

One of the surprising causes of death was “erysipelas”—known as St. Anthony’s Fire in earlier times. It is an acute streptococcal skin infection which could spread to the lymph nodes. It was indeed fatal in severe cases, right up through the early 20th century.

Other old-fashioned diseases were dropsy, pleurisy, palsy, brain fever or inflammation of the brain, croup, and “fits.” Dropsy is fluid retention in kidneys or heart, otherwise known as edema or congestive heart failure. Pleurisy is inflammation of the lining of the chest cavity. Palsy is loss of muscle control (probably Parkinson’s). Croup is Diphtheria. As for the fits, perhaps that was epilepsy, perhaps not.

Today, most of these diseases have effective treatments. Instead, we die of cancer, heart disease and stroke, automobile accidents and shootings. Note—no one died of a bullet wound in 1850’s Hunterdon County. Or at least, none was reported. However, there were four accidents (two involving horses or wagons) and 8 “sudden” deaths. Those could be accidents, heart attacks, apoplexy, or possibly gun shots.

The most common and deadly diseases were fevers of various kinds and inflammations, sometimes specified as inflammation of the brain, or of the lungs, or of the bowels. (31 deaths were due to “fever.”) The fevers could very well have been malaria. September had more deaths from fever than any other month except February which had the same number—4.

Another term was “congestive fever,” and that was definitely malaria. 16 people died of it. There were 30 deaths from consumption, 9 deaths from cholera, and 19 from dysentery, to which one could add the 4 cases of diarrhea. Most of the deaths from dysentery were children. Another cause of children’s deaths was drowning; 3 children drowned, all during the summer, of course.

There was one case of cancer (Elizabeth Brittain 65), one of apoplexy (Rebecca Hill, 47), one of an abscess (Elizabeth Fisher, 62), one of “bilious colic” (Hannah Henry, 60), and one of gout (George Heath, 47, who suffered from it for 3 years). Mahlon Hoff, a 41-year-old farmer, died of “insanity,” which he suffered from for six years. It’s hard to know how insanity can kill a person, unless Hoff committed suicide. Hoff was buried in the Kingwood Presbyterian Cemetery, age 41 years 10 months and 23 days.

One reason to think that Hoff committed suicide is the example of James Wilson who lived near Headquarters. He committed suicide in August 1865 by slitting his throat. The Hunterdon Republican reported that “he had been subject to fits of insanity.”2

No one died of suicide in 1850, probably because it was considered shameful. The usual phrase used for suicides was “not having the fear of God before his eyes, but being moved & seduced by the instigation of the Devil . . .”3 I suspect that one or two of those sudden deaths were suicides.

Two people died of “intemperance”: John Slater 54, school teacher of Lebanon twp., who suffered for four days. And Frederick Martenez, also of Lebanon, a stone mason, age 61, who died after 3 days.

Philip Young, 73, of Amwell, widower, was the only person to die of jaundice, after four days. Elizabeth Rockafellow, 62 (1788), of Alexandria Twp. (married) was the only one to die of palpitation of the heart. She may have been the wife of John Rockafellar Jr. of Alexandria Township who was born on Dec. 5, 1779. But the mortality schedule said that Elizabeth was married, and John Rockafellar died about August 1811. Perhaps that was a clerical error, or I misread the schedule.

Elizabeth Shafer 41 of Alexandria (married) appears to have died of “quinsy,” which is an abscess in the mouth, usually associated with tonsillitis. Another horrible way to die.

Who was most likely to die?

The age range was from 1 month old to 99 years old. The most likely to die were children age 7 and younger. The next most likely were age 65. Otherwise, the death rate was pretty even throughout the age range.

But the number of children who died compared to the rest is terrible. 45 children died in their first year of life. 20 died the next year and 10 the year after that. That’s 75 deaths in infants and children through their third year. Or 28% out of a total of 271 people. One of the most common childhood diseases was scarlet fever; 8 children died of it, but no adults. Another common cause was croup, of which 14 children died, and also one adult: Arthur Williamson of Raritan Twp., age 75.

The fatalities among babies is extremely sad. There were 8 babies who died one month or less of age, mostly of unknown causes. Two-month-olds got more diagnoses: diarrhea, dysentery, erysipelas and fever, and two unknown. By three months they were dying of croup and cholera, inflammation and scarlet fever. The death rate dropped after three months from 7 to 8 at each month of life down to 2-5 for those 4 to 11 months of age, until the first birthday, when 20 died. That was the deadliest year, and I really don’t know why. Perhaps by that time the babies were walking and getting exposed to more germs.

When were they most likely to die?

Deaths were seasonal. I charted the months in which people died and discovered something that most people do not expect. We all tend to think that winter is the most hazardous time of year. But the lowest number of deaths took place in November. January, February and December were also very low. The second most fatal, people tend to think, is summer, but July had the second fewest deaths, June the third fewest.

It turns out that Spring and Fall were the most dangerous. In March, April and May the most common causes of death were consumption, fever and inflammation, erysipelas, dysentery and old age. Far worse was the fall, specifically September, with the highest number of deaths (33) and October with the next highest (30). In those months people died mostly of dysentery, followed by consumption, fevers and inflammations, croup (for the young) and old age.4

Mortality then and now

I wanted to compare the death rate for 1850 in Hunterdon to the death rate in America today. According to the National Center for Health Statistics, the death rate in the United States for 2010 was 798.7 per 100,000 people.

In 1850, 271 deaths were recorded in the mortality schedule for Hunterdon County, and a total population of 28,981. That’s a death rate of less than one percent.

Here’s another way to look at it: if the population of Hunterdon County were still 28,891 people, then in 2010 only 231.5 people would have died, compared to 271 in 1850. I thought there would be an even bigger difference, but it is certainly significant. Most of the difference can be explained by the improvement in childhood mortality.

The Oldest People to Die in 1850:

Of these long-lived people, 7 men died and 9 women, which seems like a much more even match than today. Many of these people are hard to identify. Once they grew old, they lived with families and were no longer head of households. They were not listed in the main census for 1850. Many were too old to have estates recorded. So information on them is scarce. Some of these folks can be found on Find-a-Grave, but definitely not all of them.

Mary Compton of Franklin twp., 80 (born c.1770), died of “old age” after 35 days. She died on March 9, 1850, age 77 years and 7 days (somewhat less than 80). She was buried in the Grandin Cemetery, Bethlehem Township. She was a widow, and may have been married to a son of Henry Compton and Rebecca McPherson. Find-a-Grave had no Compton listed who died before 1850; no obit in the Gazette or the Democrat.

John Pursel of Alexandria twp., 81 (born c.1769), farmer, cause unknown. Find-a-Grave lists a John Pursel born on Sept. 23, 1768 who died on March 28, 1850 in Greenwich twp., Warren Co. His widow was Mary Haughawout, and he left 14 children. He was buried in the Old Presbyterian Burial Ground in Hackettstown. He was probably the son of Jonathan Pursell and Esther Moon, Quakers who moved from Philadelphia to Hunterdon County. His wife survived him. The month of his death was not given in the schedule. No obit in the Gazette of 1849 or 1850, or the Democrat.

Mary Alpaugh of Tewskbury, 82 (born c. 1768), unmarried, died Feb. 1850 of old age. Two Mary Alpaughs who died in 1850 were listed in Find-a-Grave. The mostly likely one was the Mary Alpaugh buried in the Old Lebanon Reformed Church Cemetery, who died on Feb. 12, 1850. The mortality schedule stated that the 82-year-old Mary died in February. From the Gazette, Feb. 20, 1850: DIED, Near Cokesbury, on the 13th inst., Mary Alpaugh, aged 83 years. An obit was also published in the Democrat on Feb. 20, 1850, but added no further information.

Elizabeth Young of Amwell, 84 (p. 13, line 32), born c.1766, unmarried, died in March 1850 of old age after 7 days. On the same page, a few lines down, another Elizabeth Young of Amwell was listed, age 86, (p. 13, line 23) who died in October 1849, of old age. There is only one Elizabeth Young in Find-a-Grave, and she was born on Jan. 1. 1767, died on March 7, 1850. She was buried in Amwell Ridge Cemetery. Was there a second Elizabeth Young the same age or was this just a duplication based on faulty information? No obit for Elizabeth who died in 1849 in the Gazette or the Democrat, nor for 1850.

The database information on Ancestry.com for the 1850 Mortality Schedule advises researchers to check the main census to get more details on the people who died. But I could not find Elizabeth Young there. In fact, none of the people listed here appeared in the main census. This practice must have been followed in later years, not in 1850.

There is only one Elizabeth Young who died in 1850 listed in the main census report. But she lived in Alexandria Twp., and her age was given as 87. She was the head of a household that included Mary Fitz Young age 52, and nine unrelated people, including the Samuel Eckel family. A much younger Elizabeth Young, age 62 in 1850, was living in Amwell (East & West) with the Jacob F. Prall family.

My best guess is that she was the unmarried daughter of John and Catharine Young of Amwell. John Young wrote his will on Dec. 6, 1803, naming daughter Elizabeth, along with the rest of his 12 children.

Philip Anthony of Lebanon 84, died May 1850 of old age. He was born in Sussex County on July 21, 1756, according to Find-a-Grave, and died on May 8, 1850 (age-93-9-18, considerably older than the age given in the census; it is most likely the inscription was misread and should be 83-9-18). He was the son of Philip Anthony and Elizabeth DeWitt, according to Donna Lamerson. He married Mary Moore who died in 1851. He was buried in Spruce Run Cemetery. No obit in the Gazette or the Democrat.

Samuel Phillips of Amwell, 84, farmer, died Dec. 1849, of palsy after 10 days. I did not find a listing for him on Find-a-Grave, and there was no obit in the Gazette or the Democrat. There was a rule to bar creditors from the Orphans Court published on May 29, 1850 that mentions Israel Wilson, sole executor of Samuel Phillips dec’d.5 All I know is that he is supposed to be the son of Samuel Philips (1722-1770) and wife Ruth.

Prime Moore of Amwell, black, 85 (born 1765), fiddler, died June 1850? of “chronic” after 2 months. No record of him on Find-a-Grave; no obit in the Gazette or the Democrat.

Sarah Fishbough of Bethlehem, 85, died Sep. 1849 of old age. No record of her on Find-a-Grave; no obit in the Gazette or the Democrat.

Thomas Pidcock of Amwell, 87 (born c.1763), died Dec. 1849 of dropsy after 21 days. No record of him on Find-a-Grave. I believe that his first wife was Anna Butterfoss (born Feb. 1, 1776), daughter of Daniel Butterfoss Sr. and Esther Ent. Thomas was the son of Philip Pidcock of Solebury, Bucks County. Thomas and Ann had six children, of whom I know nothing. His second wife, Hannah, was the granddaughter of Walter Wilson, whose will dated 1823 left a house and lot of land to Hannah and her husband Thomas Pidcock. No obit in the Gazette or the Democrat.

Rachel West of Kingwood, 87, died in August 1849 of dysentery after 2 weeks. No record of her on Find-a-Grave. She may have been Rachel Hoagland, born in England about 1768, wife of Thomas West of Scotland. They settled in Alexandria Township and had 8 children. She may have been the Rachel who married Edward West, born about 1757 Kingwood and died after September 1850. This Rachel died in August 1850 in Kingwood. No obit in the Gazette.

Sarah Kline? of Kingwood, 88 (born c. 1762), died Oct. 1849 of dysentery after 3 weeks. No record of her on Find-a-Grave; no obit in the Gazette or the Democrat.

John Ent of Delaware twp., 88 (born c.1762), died of fever after 20 days. He died on January 8, 1850 and was buried in the Sandy Ridge Cemetery in Delaware Twp. There are 24 other Ents buried there. John Ent was the son of Daniel and Elizabeth Ent. He married wife Rebecca about 1785 and they had five children (Susan, John, Catharine, William and Ury Ann). He wrote a will, but I have not seen it. Wife Rebecca died in 1855, age 92. No obit in the Gazette or the Democrat.

Rebecca Runkle of Amwell, 89 (born c.1761), died in May 1850, cause of death unknown, 5 days. No Rebecca in Find-a-Grave; no obit in the Gazette or the Democrat.

Tunis Trimmer of Franklin, 90 (born c.1760), died Sept. 1849, of “dry metroperitonitis,”6 after 120 days. Not in Find-a-Grave; no obit in the Gazette or the Democrat. However, there was a Henry Trimmer, born Dec. 3, 1767, died Oct. 5, 1850, who was buried in the Lower Amwell Cemetery, Old Yard. This was not the same person because he died after June 1, 1850. It appears that the Trimmers were long-lived people.

Lena Schamp of Readington, 96 (born c.1754), died in July 1849, of fits. I do not have information on her, and did not find her in Find-a-Grave; no obit in the Gazette or the Democrat.

and the winner in the longevity race: Margaret Sheppard of Raritan Twp., 99 years old (born c.1751), married, who died of old age in October 1849 after only 3 days. I thought she might have been married to Richard Shepherd of Amwell (Delaware twp) who died in 1830, but his wife was Mary Servis, daughter of John Jurien Servis. Perhaps this Richard had a second wife we do not know about. On Find-a-Grave, a Richard Shepherd who died in 1830 is listed in the Harbourton Cemetery, husband of Mary Servis, and son of John Shepherd and Margaret Shepherd Wambough Bearder. That Margaret was buried in Amwell Ridge in 1800. Margaret Sheppard did not have an obit in the Gazette, but on Oct. 3, 1849, the Democrat reported the death of Mrs. Margaret Sheppard, “on Monday morning last, near Flemington, aged 100 years.” No other information.

Postscript:

The Democrat published (on Jan. 1, 1851) a list of the oldest citizens counted in the Census of 1850, as follows:

- East and West Amwell: Andrew Butterfoss 97, Peter Wilson 87, Ellen Yorks 90, Letitia Cook 89.

- Lambertville: John Holcombe 81, Esther Davis 95.

- Delaware: Edward West 93, Sarah Bolt 93.

- Raritan: Daniel Moore 87, Jane Carman 91.

- Kingwood: Richard Heath 90, Sarah Taylor 100.

- Franklin: Christy Little 89 (since deceased), Usida {?} Deats 84.

- Alexandria: William Case 89, Rosannah Ellicott 94.

- Bethlehem: H. W. Hunt 81, Catharine Vansyckel 88

- Clinton: Thomas Leonard 92, Sarah Johnson 97.

- Readington: John T. Van Fleet 88, Margaret Latourette 93.

- Tewksbury: Daniel Potter 88, Catharine Henry 92.

- Lebanon: Henry Hann 87, Mary Dilts 92.

Addendum:

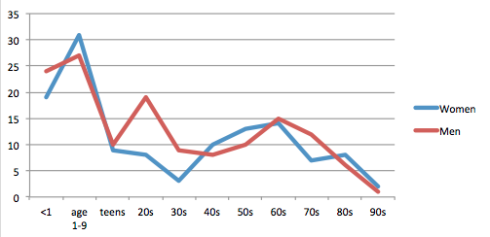

In response to Kay’s comment, here is a chart showing the comparative ages of men and women when they died in 1849-50. The left-hand column shows the number of people who died at each age bracket.

Footnotes:

- From the article “Mortality Schedules: Unlocking the Mystery” by Echo King AG, published on the Ancestry.com website. ↩

- H. C. Republican, Sept. 1, 1865, as abstracted by William Hartman. ↩

- From the coroner’s report on the death of Isaac Vancamp in 1809, report #830, Hunterdon Co. Surrogate’s Court. ↩

- This phenomenon is described in John Demos’ very interesting book Circles and Lines; The Shape of Life in Early America (on p. 14). I recommend it. ↩

- I searched for both Phillips and Philips. ↩

- That is how the Ancestry.com indexer read it, which is better than I could do, but does not sound right. ↩

Sharon Moore Colquhoun

October 31, 2014 @ 7:02 am

Marfy, I’m always amazed at the people who lived to be over 100! Penelope Stout of Hopewell lived to tell her descendants about her times with the Native Americans. I have another great grandmother in Orange County, New York, who also lived to be over 100. By the time of their deaths, they each had over 300 descendants. I also have TWO ancestors (one on each side!) who escaped the “Indians” by hiding in a tree. One of those was Penelope Stout. The other one was Zopher Hawkins of Setauket, Long Island. Then, my Moores supposedly lived in a tree while building their house. And many kids today think history is boring.

Marfy Goodspeed

October 31, 2014 @ 10:13 am

Sharon, I also have an ancestor who was hid from the Indians as a little girl, beside a log instead of in it, and this was near Lake Ontario. She also lived to a ripe old age. Perhaps surviving childhood diseases made people stronger.

Kay Larsen

October 31, 2014 @ 8:00 am

Thank you, Marfy, for another really interesting article. I am always amazed at the people today who say (with great certainty and a certain amount of arrogance) things like “people only lived to be about fifty or sixty in the 1800’s”. Obviously the term “AVERAGE life span” does not resonate with them. I come from a long line of ancestors of whom most lived to be in their eighties and one, born in the very early 16th century (a direct Connecticut ancestor), made it well into the first decade of the eighteenth century, dying at 103 yrs. of age.

I was surprised to note that there were no deaths from childbirth listed in your article, though I have found in my own research that if a woman lived a few days or a couple of weeks after the birth, her death was often attributed to other causes, which they did not seem to connect with the birth itself, at least not on paper, but which today would be listed as a complication of childbirth. Have you ever noticed that in your own research?

Marfy Goodspeed

October 31, 2014 @ 10:14 am

Hi Kay,

Actually there was one death from “child bed,” which no doubt is what you are referring to. But only one, which surprised me. Both my grandmother and great-grandmother died of it. Perhaps 1849-50 was just a lucky year for women. Which reminds me–I forgot to see how many men v. women died altogether.

Kay Larsen

October 31, 2014 @ 5:41 pm

To me dying in childbed means dying during labor or in the immediate post-partum period (a day or two). I am referring to women who died not in the immediate period after labor, but say within the first six weeks. For instance, my great-grandmother’s sister died a few weeks after the birth of her child and the cause of death is listed as “Marasmus” which was defined in that time as “wasting or decay of the entire body and vital forces, as from long continued pain, loss of sleep, starvation, etc. [Appleton1904”. Today it is associated more with the child than the mother. At any rate, no mention on her death certificate was made of her having borne a child recently. I am thinking that the birth had to have had something to do with that (possibly a severe post-partum depression). And I am thinking of women who may have been diagnosed with pneumonia or a heart problem several weeks after delivery who may actually have died from a pulmonary embolism. I’ve seen several death certificates of women who died within weeks of the birth of babies, but the deaths are not listed as childbirth related. Too coincidental.

Neil Cubberley

November 1, 2014 @ 11:48 pm

A lot has to do with the “lifestyle”. In 1850 Hunterdon County was much more rural than the cities. They were predominately farmers who got a lot of exercise and ate and sold natural foods.

Then you have to look at conditions and diseases. My grandparents and great grandparents all lost multiple children from being stillborn, the flu and cerebral palsy. all of which are rare now.

Mercedes Hayes

October 31, 2014 @ 10:10 am

Great article, Marfy. What a terrific snapshot of rural America.

Ron Warrick

October 31, 2014 @ 1:21 pm

The CDC has national death rate tables going back to 1900, at which point the rate was 1,719.1 per 100,000. The rate was dropping over time and was down to 1468.0 by 1910, still without benefit of antibiotics, so we can expect that the death rate in 1850 was significantly higher than than 1719 per 100,000. If Hunterdon County’s rate was less than 1% in 1850, it was a relatively very healthy place to live.

http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/mortality/hist290.htm

Kay Larsen

October 31, 2014 @ 4:44 pm

My bet is that, relatively speaking, any rural area was a healthier place to live than in the crowded cities with sewage and sanitary facilities less than adequate. The crowding itself certainly leant to the spread of whatever disease was going round at the time.