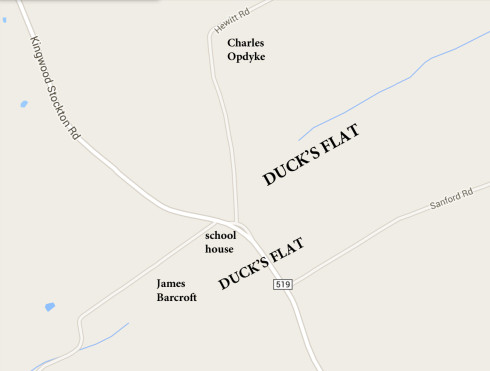

Last week I posted a continuation of Egbert T. Bush’s article “The ‘Oregon’ and Other Schools,” focusing on the neighborhood once known as Ducks’ Flat. Mr. Bush wrote about Duck’s Flat in 1930. This was two years before a surprising event took place there. Given that the participants stayed at the Stockton Inn, near where Mr. Bush lived, I can’t help but think he knew about the goings-on. But he did not write about it. It wasn’t until 1996 that another talented writer described what happened at Ducks’ Flat—an early experiment in rocket science, which took place on November 12, 1932.

The writer was Bruce Palmer, and his tale was published in the Lambertville Beacon on November 13, 1996. (Note that Mr. Palmer’s article is in italics, and my comments are not.)

Stockton center of rocket science—long ago

Mention space flights, rockets or astronauts and the names that pop up include Cape Canaveral, Houston Control Center and maybe Peenemunde, the launch site for V-2 rockets fired by Nazi Germany against England in WWII. But for one shining moment—actually more like 15 seconds—the center of rocket and space science was a windy farm field north of Stockton. Sixty-four years ago, four members of the American Interplanetary Society and the wife of the organization’s first president ran a static test on a gleaming, sleek projectile they called Rocket #1.

The five members of the Experimental Committee of AIS (later renamed the American Rocket Society) were weekend guests at Colligan’s Inn, now known as the Stockton Inn.

The five members were Gawain Edward Pendray, science editor of the New York Herald-Tribune, Hugh Franklin Pierce, an engineer, Dr. William Lemkin, David Lasser (president of the AIS), and Mrs. Pendray, introduced as Laetitia Gregory, Pendray’s executive secretary

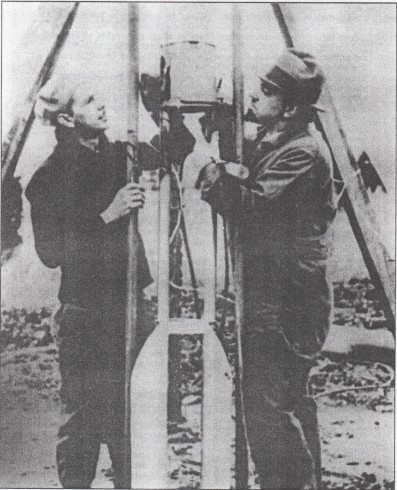

The steel launching rack had been fabricated by Anton ‘Tony’ Schuck at the garage in Stockton now operated by his son, Richard. The angle-iron and channel were hauled by wagon to what was then called Holbrooke’s farm near Rosemont, welded together and braced upright with four wide-spread wooden legs.

In the middle of the field, two “bomb proofs”—shallow pits fronted with sandbags—had been gouged out of the cold mud.

A photographer had been persuaded to be there in order to record the event, just like the Wright brothers’ exploit at Kitty Hawk.

Rocket #1 , co-designed by Gawain Edward Pendray and Hugh Franklin Pierce, had been hand made in New York City of near-pure aluminum, just then coming into its own as the ideal lightweight metal for aircraft construction.

It was 9 inches in diameter and stood 7 feet tall on tubular legs tipped with large, flat fins. The device was remarkably light; loaded with gasoline under 90 pounds square inch pressure and liquid oxygen, it tipped in at only 15 pounds.

Not one member of the AIS launch team at what Mr. Pendray rather grandly called “the proving ground at Stockton” had actually test-fired or launched a liquid-fueled rocket. Hence the “bomb-proofs,” crude shelter in case of an explosion. The motor itself, a cast aluminum combustion chamber only 3 inches by 6 inches, had never been tested either.

Nov. 12, 1932 was a cold, windy day, with rain in the afternoon. The experimenters were delayed by a dozen unexpected glitches. Most critical was the remote control ignition system, a number of gauges and switches mounted on a plywood pane and connected to a 6-volt battery. Somehow, it shorted out in the rain and refused to work.

The “bomb-proofs” were filling up with icy water as the rain came down. Mr. Pendray was wearing a suit, tie and trilby hat. The others were not any better prepared. The photo-journalist from “Acme Newsphoto” was ready to leave, but Mr. Pendray, a larger-than-life personality, persuaded him to wait a little longer. The rain, wind and fading light made a rocket launch impossible, but the rocket motor could still be tested, and it might be spectacular.

The “bomb-proofs” were filling up with icy water as the rain came down. Mr. Pendray was wearing a suit, tie and trilby hat. The others were not any better prepared. The photo-journalist from “Acme Newsphoto” was ready to leave, but Mr. Pendray, a larger-than-life personality, persuaded him to wait a little longer. The rain, wind and fading light made a rocket launch impossible, but the rocket motor could still be tested, and it might be spectacular.

November was not a good time of year for such work. It had originally been planned for August, but things kept going wrong. Pierce, who preferred the name Frank, in honor of his ancestor, President Franklin Pierce, used drawings that Pendray had obtained from German scientists to design a new and improved motor. Except he had never built a rocket motor before, and every part had to be custom made.

Mr. Palmer was unable to find out who chose Stockton and Ducks’ Flat for this event. But it made sense. It was convenient for New Yorkers who could take the train to Trenton and then get the Bel-Del rail line north to Stockton, the location of the only decent hotel along the Delaware (today’s Stockton Inn). Even better, there was a convenient garage to supply gasoline and extra parts. Surrounding Stockton was a large area of open, mostly unpopulated farmland, ideal for a test site.

Why not postpone the experiment until spring? Pendray was too eager for recognition. He was in competition with the famous, but reclusive, scientist, Robert Goddard, and a big headline would bring Pendray the attention he wanted. Mr. Palmer continues:

Back in 1926, Dr. Goddard had flown his own version of a liquid-fueled spacecraft for a grand total of 2.5 seconds before the motor melted. The rocket had lifted 56 feet into the air. Burn-out was a problem, but Mr. Pierce and Mr. Pendray had reason to believe they might have a solution.

It was still Prohibition in 1932, but Bill Colligan kept his bar. Where there’s a bar, there’s crushed ice. The AIS launch team needed crushed ice. The combustion chamber locked into a cooling jacket that was to be packed with ice. Mr. Pendray bought a thermos bottle for $1 on the morning of the launch, presumably to get the ice from Colligan’s to the launch site. . . .

The late Eugene Reading, born and raised in Rosemont, was then a teen-ager, living next door to Colligan’s. He remembered “the well-dressed strangers from New York,” but believed the chief figure to have been Dr. Goddard, for whom Mr. Reading later worked during the early years of NASA.

This just shows how easy it is to mis-remember things. Mr. Reading had no recollection of Frank Pierce, but Palmer deduced that Pierce had been to Stockton a couple weeks earlier and presented his drawings to Anton Schuck for construction of a “launching rack.” He may also have met Egil Hohe, who was identified in notes as the “site contact man.” Such an unusual name—who could he have been?

Although the AIS kept detailed financial records on costs, there is no indication that the organization paid any sort of rent or fee for the use of the field. A single $10 bill for “materials labor and services” may have covered everything supplied by Schuck’s Garage.

“My dad never talked too much about it,” Richard Schuck remembered. “It wasn’t that important. The launch frame was easy work for a competent welder, although it was custom-built and had to be hauled to the field. People in town seemed to have thought these people were no more than friendly crackpots, willing to spend some money, presumably harmless, who were just fooling around at something.”

This would explain why Egbert T. Bush never bothered to write about the ‘friendly crackpots.’

“The steel and lumber was hauled up to what is now the Michelenko property,” Mr. Reading remembered. “I was dying to go watch it all with some pals of mine. It was deer season, and I had done some hunting up in that area, of course. But my mother got wind of it and wouldn’t let me out of the house. On a Saturday, too! Word had gotten around that these New York folks were going to explode some sort of bomb up there, and she was certain that I’d get too close and be blown to bits!”

Nobody from Stockton, not even the property owners, seems to have observed what actually happened. Mr. Pendray’s papers say that since the electrical igniter did not work, David Lasser volunteered to touch off the motor fuse, using a crude torch made of rags soaked in gasoline. One of the Acme photos shows Mr. Lasser, in his shirt-sleeves, torch in hand, running for cover, the motor already spewing flames.

“In an instant,” Mr. Pendray wrote, “there was a great flare, as the pure oxygen struck the burning fuel . . . The gasoline was also pouring into the rocket motor. With a furious, hissing roar, a bluish-white sword of flame about 20 inches in length shot from the nozzle . . . and the rocket lunged upward against the retaining spring.”

The small group of experimenters was so excited by this, Mr. Pendray admitted, that they all “forgot to count the seconds, as they passed, in that downward-pouring cascade of flame.”

Mr. Pendray made some claims about the success of the test, but they were “roughly 10 times longer, bigger or better than anything Dr. Goddard (or the Germans) had yet achieved.” The following day, the weather continued bad, and the rocket had been blown off its platform, so further tests were cancelled, and the group left Stockton Sunday evening to return to New York.

All except Frank Pierce, who waited until Monday to bring the rocket paraphernalia back by train. Adding the cost of Pierce’s rail freight and his extra room and board brought the total expenditure to $99. The AIS received $98 in royalties from sale of the photographs taken of the test. Bruce Palmer asked:

Was the Stockton test worth doing? It would seem so.

Mr. Pierce noted that the fuel lines had nearly clogged with frozen vapor, a promise of high-altitude engine failure unless somehow solved. The aluminum nozzle that concentrated the thrust had partly melted, despite the ice jacket cooling.

The AIS urged that liquid oxygen be used to prevent meltdown. That idea was promptly adopted, in this country by Dr. Goddard, and by scientists abroad, including a promising young graduate student in Berlin, named Wehrner von Braun, creator of the V-2 ballistic rocket a decade later.

What happened to Rocket #1? The following spring, repaired, improved and renamed Rocket #2, it rose from Red Hook, N.Y., reaching a height of 200 feet, an unofficial world record at that time.

But it blew up, a grim precursor of all the rocket disasters the world has witnessed since.

G. Edward Pendray was born on May 19, 1901 in Omaha, Nebraska, but he lived in Jamesburg, NJ for many years, and died on Sept. 15, 1987 at Cranbury, NJ. He and wife Leatrice M. Gregory married in 1927. After the New York Herald-Tribune, he was science editor for Literary Digest until 1936 when he was hired by Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Co., with responsibility for public relations at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York. While there, he coined the word ‘laundromat.’

Pendray, despite his competition with Robert Goddard, ended up editing Goddard’s papers with his widow. The American Rocket Society, formerly the American Interplanetary Society, in turn became the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA), which gives out the “G. Edward Pendray Award.” In the 1950s, Pendray was involved with the Guggenheim Institute of Flight Structures at Columbia University, and the establishment of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.1

Unlike Mr. Pendray, I found very little about Hugh Franklin Pierce online, except for one important fact. In 1941, Frank Pierce joined with Lovell Lawrence, Jr., John Shesta and James Wylde to create a company called Reaction Motors, Inc. and acquire a Navy contract to develop rockets. The company eventually built the XLR-11 rocket engine that broke the sound barrier in 1947.2

What became of Frank Pierce after that I cannot say.

Bruce Palmer was born one month after the rocket test at Ducks’ Flat, in Boston, Massachusetts. He lived in Stockton for many years while teaching in various schools in New Jersey. He was an author whose books included “They Shall Not Pass” about the Spanish Civil War, “Last Bull Run” and “Chancellorsville.” He also wrote articles for local newspapers, including the Lambertville Beacon. Bruce Palmer died on November 7, 2014 at the age of 82, five days before the 82d anniversary of the rocket test. I’ve had this article sitting in a drawer for several years now, thinking to someday write about this wonderful incident, but it never occurred to me to speak with Bruce Palmer. I am three months too late.

Mr. Palmer ended his essay with this question:

Why isn’t Rocket Day at least a local holiday in the borough [of Stockton]? Surely such an historic near-event should not be forgotten.

No, it should not. I am marking my calendar for November 12, 2015, and planning on a trip to Ducks’ Flat to make a toast with some less explosive, but still effervescent liquid fuel. Anyone want to join me?

Post Script: The eastern fringes of Ducks’ Flat may become far less peaceful if plans for a natural gas pipeline get approved. The proposed route will run along the abandoned part of old Hewitt Road, close to the home of Tommy Robinson, then down the east side of Ducks’ Flat on its way toward Rosemont. If this should come to pass, there will be some lamentations at the celebration.

Footnotes:

- From the article on Pendray in Wikipedia. ↩

- NASA Image Gallery. ↩