In his diary, Benjamin Ellicott made several references to his father-in-law, Elisha Warford. Warford is a legendary figure in the history of the Locktown-Croton vicinity, so it seems appropriate to publish Mr. Bush’s recollections of the man. He was a controversial figure, extremely wealthy, and extremely litigious. He never hesitated to take his debtors to court, as the papers in the Warford Collection at the Hunterdon County Historical Society will attest. Warford was a difficult personality that Mr. Bush managed to write about without casting aspersions. But then Egbert T. Bush was always a gentleman. As usual, I will take the liberty of making comments and annotations.

Elisha Warford, Wealthiest Citizen of Croton Village

Stern Old Resident Accumulated a Large Fortune and 1,000 Acres

Bought Piano for Daughter

by Egbert T. Bush, Stockton, NJ

published by the Hunterdon Co. Democrat, July 2, 1931

For various reasons, I wanted to visit Croton. My young friend, Frank Carver of Rosemont, probably mistrusting uneasiness, volunteered to take me wherever I wanted to go. So Croton it was. I wanted to see the ruin wrought by the recent fire, to sympathize with the people and with the good old place for the frequent losses by the same agency. I wanted to see again some of the heirlooms held by the Ellicott family, as well as the antiques rescued from the fire and others gathered from numerous sources. But most of all, I wanted to gather data on the life and activities of that remarkable old man, Elisha Warford, memory of whom is still fresh after three score years.

The reason Frank Carver did not want Mr. Bush to go to Croton on his own was probably the fact that at this time, Mr. Bush was 83 years old, and probably getting a little frail. Frank Carver was a 27-year-old school teacher who lived in Rosemont with his wife Dora Reading. He was the son of William S. Carver and Laura B. Emmons.

Among the many family relics is found an interesting old piano, one of the finest of its day, made over a hundred years ago by a German named Hoppman, whose factory was in Baltimore, and who took pride in making fine instruments for those who could afford them. Two pianos and only two were made just alike and called the “Dolly Madison.” One of these went into the White House, then the home of President Madison; the other was bought later by Elisha Warford for his daughter, Mary Ann, then nine years old and living with a relative named Rachel Colvin in the city of Baltimore. The price paid was $1,000—a big sum for that day. But it was a fine instrument of exquisite workmanship, with a lion carved from wood and couchant at the feet of the player.

Rachel Colvin was born about 1745. I have struggled to find out exactly how she was related to the Warford family, but have not found anything definitive yet. The common relatives were James Warford (1751-1822) and wife Rachel Cain (c.1755-c.1834). After Rachel Colvin’s death, both Warfords and Cains claimed to be heirs-at-law. My best guess is that her parents were John Colvin (c.1715-1771) and Elizabeth Warford (1723-1777), daughter of John Warford and Elizabeth Stout. Elizabeth Warford was the great aunt of Elisha Warford, making Rachel Colvin and Elisha Warford first cousins once removed. John and Elizabeth Warford Colvin moved to Hampshire County, Virginia around 1742, so Rachel Colvin was probably born there.

Many Fires at Croton

Croton has suffered much from fires during its life as a busy hamlet. In 1847 the store house and all its contents were destroyed. The upper story was filled with flax dressed and ready for the city market. This is said to have made it a spectacular fire. But the dwelling house only a few feet away was saved. The property was then owned by John Hockenbury, who immediately built another house on the old foundation. This was burned down some sixty years later, and again the dwelling house was saved. The wheelwright shop on the southeast corner, so long labeled “Jersey Square” in bold and symmetrical letters by an unknown artist, was burned down in 1885. Here Holcombe Warford, son of Elijah, worked at this trade from 1838 and for many years kept the post office. He rebuilt the shop near the site of the old one, but died soon after. In 1886 the property was sold to George W. Ellicott, whose brother-in-law, George Cronce, kept a store there for many years and was then succeeded by his son, Lambert T. [sic] Cronce.

John Hockenbury has appeared frequently in previous posts. (I suggest entering his name in the search box above to find all the articles.)

Holcombe Warford was born about 1812, the only child of Elijah Warford and Amanda Holcombe, making him the nephew of Elisha Warford. He married Margaret Case (c.1812-bef 1880), daughter of George Case. Margaret Warford Case must have died before the 1880 census, for in that year, Warford was living with his daughter Emeline and her husband William R. Cronce. He was 68 years old, widowed, and still a wheelwright. He died on October 11, 1886, age 75 years 6 months.1 His wife Margaret seems to have died on January 11, 1879 and was buried as Margaret Case, wife of Holcomb Warford, in the cemetery at Cherryville.2

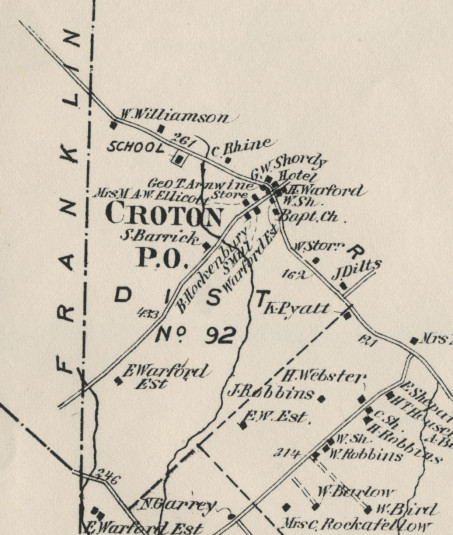

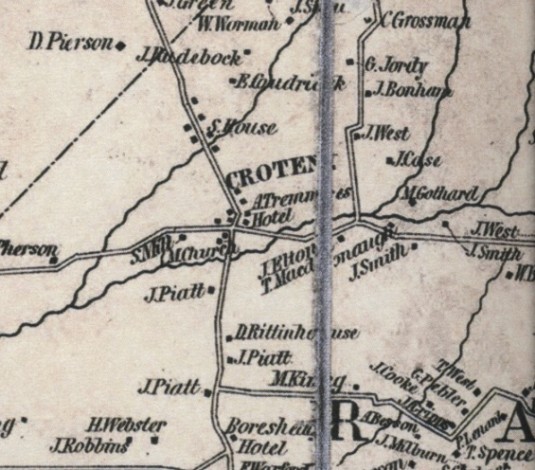

The 1851 Cornell map shows that the hotel and residence of G. W. Shordy was occupied by A. Trimmer; the school appears to be on the Raritan twp. side of Rte 579, and also shown were the mill and the church.

George W. Ellicott (1858-after 1930) was the grandson of Elisha Warford, youngest child of Benjamin H. Ellicott and Mary Ann Warford. Lambert T. Cronce was actually Lambert P. Cronce (1866-1941), according to his gravestone. (The only census record that shows his initial is the 1940 census, but to me the initial is unreadable.) The connection between Cronce and G. W. Ellicott is that George W. Ellicott was married to Sarah M. Baker, sister of Mary Ellen Baker who married George Cronce, and had son Lambert P. Cronce. The sisters’ parents were Peter H. Baker and wife Matilda Dilts.

Other fires in and near the hamlet have been too numerous for comfort. But the most destructive of all was the fire of February 3, 1931, which broke out in the barn on the old sawmill property. From this the southwest wind carried sparks or burning fragments a hundred yards to the big Ellicott barn, which was destroyed with contents valued at $7,000, mostly antiques. From this barn the fire was carried to the old one on the original store property. This too was entirely destroyed, but again the dwelling house was spared. Ellicott had partial insurance on his building but none on the contents. He takes his loss philosophically, and rejoices that the house did not burn with its many precious relics, tho the sparks flew over the house and started fires between it and the barn.

Elisha Warford

However, the chief object of this visit was to find matters relating to the life and family of Elisha Warford, so well known over a wide circle in the earlier days for his appearance, his disregard for conventionalities in dress and language and for his remarkable success as a speculator in local real estate.

Mr. Bush is not playing fair with us—having mentioned Warford’s appearance, he should have told us more. (For a man of such prominence, it is surprising we do not have a portrait of him.) And what about his language? In what way did he disregard conventionalities?

Elisha Warford was a son of James Warford, whose wife was Rachel Cain, daughter of Walter Cain, living on a farm west of the Boarshead Tavern. Elisha was born in Kingwood Township, October 20, 1785, on the homestead farm west of Locktown. In 1806 he married Mary Arnwine. For some reason the Family Bible records their ages as well as their names: his age as 20 years and six months; hers as 30 years and five months. 3

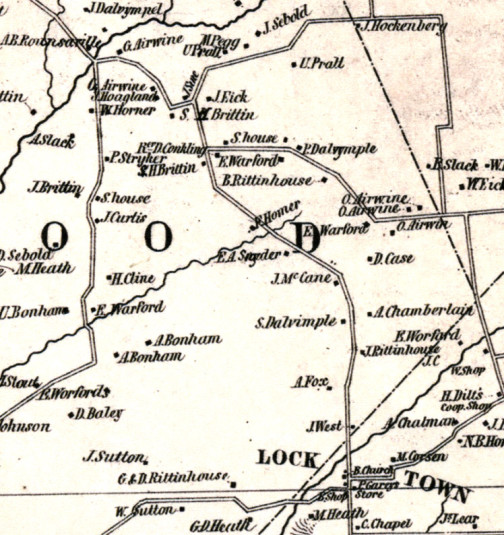

They settled on a 50-acre farm east of Slack’s School-House in the vicinity often called Slacktown. There he carried on farming in connection with his trade as a wheelwright and maker of plows with wooden mouldboards. We are told that two such plows were a day’s work for the ambitious young man, while a forgotten number of “cuts” was a day’s work at spinning for the equally ambitious wife. Here they worked and saved for ten years, at the end of which the accumulation amounted to $10,000. How could they? We have no details. Some of that money was made by hard work and some by strict economy; and no doubt a considerable part by shrewd speculation. Certainly none of it was made by dashing aimlessly about in fine cars, or even indulging in showy carriages and fine teams or any other extravagances.

As Mr. Bush wrote, Elisha Warford married Mary Arnwine in 1806. She was born on March 30, 1775, the daughter of John Arnwine Sr. and Elizabeth Opdycke. They had at least three children, two of whom died as infants (Rachel and James). The third was daughter Mary Ann, born on December 11, 1815. Mary Arnwine Warford died, age 43, on December 15, 1818.

Married B. H. Ellicott

They had five children, but only one lived beyond early childhood. This was the daughter Mary Ann, who grew up in Baltimore and married Benjamin H. Ellicott, of Ellicott’s Mills near Baltimore, where she lived until 1861. Then she returned to Hunterdon County with her husband and family. Two years later, while engaged in remodeling the Warford dwelling as a home for them all, Ellicott was taken with a fever and died September 23, 1863. His wife died February 25, 1892.

Elisha used to say that after saving the first $10,000, financial matters were easy. But the path of life was not all rosy. December 15, 1818, the wife, Mary Arnwine Warford, died. Elisha then broke up housekeeping and went with his little daughter to live with his mother on the homestead farm near Locktown. There he remained for three or four years. Meanwhile he married Elizabeth Arnwine Carrell, widow of Samuel Carrell and sister to his first wife. The only child born to them was Rachel Margaret, born February 22, 1822; died very young.

When Mr. Bush states the Elisha Warford and daughter Mary Ann went “to live with his mother on the homestead farm near Locktown,” I assume he meant the farm somewhat west of Locktown where James and Rachel Cain Warford lived, near Slacktown.

The Cornell Map of 1851 shows “E. Warford” at a few locations at or near Slacktown and on the road to Barbertown. A deed search would be required to pinpoint the location of this parents’ homestead.

James Warford wrote his will in 1813. His will left his farm to his widow and named his sons Elisha and Elijah as executors. But the will was not proved until 1822. Perhaps Elisha and daughter did not move to the home until after that year.

When Elisha Warford brought his daughter Mary Ann to Baltimore to live with cousin Rachel Colvin, he was probably preparing to marry his second wife. But that second wife, Elizabeth Arnwine, was already the child’s aunt, so one wouldn’t expect there to be any particular problem. It is merely suggestive.

Warford Active Many Years

In 1855, Elisha Warford bought of Elizabeth Cowdrick the old Aller property at Croton, to which he soon after removed. He was then 70 years old, but kept up an active business along his chosen line for a long time thereafter. He died at his Croton home May 16, 1872, leaving a large landed estate. It was said that at one time he could walk from Croton to Locktown, all of the way on his own land, a distance of about three miles. This block covered 1,000 acres or more, without counting his many scattered tracts. He now lies at rest in the neglected old Opdyke Burying Ground near Headquarters. How this first came to be selected as a place of burial is told in this interesting story:

“Old John Opdyke,” the wealthy builder of the Headquarters Mill and Mansion House, as well as of other mills and mansions in Amwell Township, was strolling [with his wife] one summer day over their wide acres of prosperous farm land. Coming to a fine shade tree then on this spot, they halted for rest, and the wife said: “John, I want to be buried under this tree when I die.”

The wife died, and John remembered. She was buried here, and here she now rests with her husband and many others. But the tree was gone long ago. There is plenty of shade, such as it is; but it is far from being the fine shade and the pleasant verdure which her eyes beheld, and which her imagination pictured for the future. John set aside a liberal area, and had all surrounded with the conventional stone walls. He provided for a perpetual right of way to and from the grounds. The pity is that he did not, out of his abundance, establish a fund for perpetual care of the grounds, the fences and the graves.4

Warford’s First Money

But we were talking of Elisha Warford, rather than of his final resting place. He used to tell how he got the first money he ever had. His father gave the boy Elisha what stools of timothy5 remained along the fences after the crop was gathered. The boy took a knife, clipped the stools one by one or as they happened to stand, dried the heads and threshed out the seed, winnowing it no doubt in nature’s broad mill, with an old sheet for a floor and the passing breeze to carry out the chaff. Then he sold the seed, and was on his way. That was his start in making and saving money; and he kept on making and saving during all of his long life.

This recalls a later gathering of timothy seed in the same way. But there are differences. This time the boy [Mr. Bush is referring to himself] did not sell the seed, did not get a cent or even a word of encouragement, and did not start then or at any other time on the way to fortune. Yet it did seem worth while then, and does so seem today. The stools were so tall and straight and the heads so fine and full and beautiful! Really it does appear that money, tho so necessary, is not the chief benefit to be received from honest labor.

Much Interest In Daughter

In spite of deep absorption in business, Elisha Warford always took much interest in his only daughter, tho he could see very little of her because she lived so far away— “away down in Baltimore.” As the wealthy unmarried members of the Colvin family died, Rachel Colvin with whom Mary Ann had spent most of her young life, grew richer and richer. It is said that she made her will, giving Mary Ann a liberal share of her estate. But as she grew feeble, a year or so before her death, some distant relative was thought to have induced her to make another will, giving him the lion’s share.

The will favoring Mary Ann was made in 1845, after Miss Colvin had suffered a bout of illness. The second will was made in 1848, when Richard Colvin Warford had moved into the house, and before Miss Colvin was ruled a lunatic.

As this developed after the death of Rachel Colvin, the fighting blood of Elisha Warford was thoroly [sic] aroused. The matter got into the Court and became a famous “will contest.” Warford left no stone unturned. He made three trips to Ohio in connection with this business, each time riding the same horse. From the third trip, tho Elisha came back all right, the horse never returned. It became necessary for Warford to go down the Ohio to find certain parties. Leaving the horse, as he supposed in good hands, he took a steamer, went about his business and returned three weeks later. It was night and the stable was dark, but Warford must visit his horse before attending to anything else. As he opened the door, he was greeted by a plaintive whinny from the animal. He went into the hall and questioned with his hands how the horse had fared during his absence. The answer was plainly given by the prominent ribs and outstanding hips. That was enough. He sought the proprietor and expressed himself with characteristic emphasis. The man grew angry, rushed out and threw a half bushel of oats, as nearly as could be learned later, into the box for the starving horse. Next morning the horse was dead. Soon two men came around with a knife and a pair of pincers. “What are you going to do?” they were asked. “Take off the skin an’ the shoes; no use feedin’ them to the fishes,” was the bantering reply.

Horse Floated Down the Ohio

“No you don’t!” roared Elisha. “That horse belongs to me just as he is, and he goes floating down the Ohio that way. Don’t you dare touch him!” And they did not. Then he paid others well to take the carcass out to the middle of the stream and throw it overboard. And that was characteristic of that stern old man, “ ‘Lish Warford.”

How odd that the sentimental thing to do was to dump the entire horse into the river. Apparently that was the ordinary way of disposing of dead horses, and other kinds of livestock. Imagine what it must have been like down-river.

When the trial of the will case came up, Warford was there and so was the best counsel to be had. He had spent thousands of dollars already, and was determined to fight it out. It became quite a noted case, as I well remember from hearing discussions of the reports as they came up from Baltimore. Elisha won the suit. But for some reason not understood here, the order was that the sum involved should be held in Court for a certain length of time. We are told that the matter was not fully adjusted until after Elisha Warford’s death.

The initial case was heard in the County Circuit Court of Baltimore and reported at length in the Baltimore Sun. A great deal of information was provided about the habits and personalities involved, which seems to have fascinated the Sun’s readers. What Elisha Warford attempted to do was have the estate divided among the heirs-at-law, rather than go almost entirely to Richard Colvin Warford.

Had Three Children

Benjamin H. Ellicott and Mary Ann had three children: Rachell W., who never married, died during the great flu epidemic; Benjamin W., now a lawyer of Dover, N.J., married Mrs. Amelia Masterson, a stepdaughter of Rev. A. F. Love, pastor of the Croton Baptist Church, 1875 to 1884; and George W., who married Sarah M., daughter of Peter H. Baker. They have had two children: a daughter Mary, who died at the age of five years; and Benjamin H., who married first a daughter of Judiah Ewing by whom he had a son, Warren E., who married Rachel Slack, lives at Croton and does the expert mechanical work in repairing antiques for his grandfather. The first wife died, and Benjamin H. married Elizabeth, daughter of William W. Case, the accountant, and now lives in Flemington.

It is natural that a man like Elisha Warford should have severe critics. He had them, but he also had friends and defenders. No doubt he had his faults—and who has not? He surely had his good qualities also. One thing stands out clearly in my memory concerning Elisha Warford and how his critics spoke of him. Among the most severe of these, I never saw one that would not make this concession which was almost certain to be offered by some one if not volunteered by the critic: “But he will never distress an honest tenant.”

Like charity, that covereth a multitude of—mistakes and idiosyncrasies. Let this be our conception of an appropriate epitaph over his lonely grave: “He Never Distressed an Honest Tenant.”

Footnotes:

- Ancestry.com database of NJ Death Certificates. ↩

- Find-a-Grave gives the death date as 1889, which is incorrect, and birth date as 1831, which is impossible since she was married in 1834. ↩

- I looked for the family bible at the Hunterdon Co. Historical Society, but was unable to find it. ↩

- For a description of the known graves, see “The Opdycke Cemetery.” ↩

- A stool of timothy is a clump of timothy grass in the ground. ↩

Susan Pena

May 1, 2015 @ 9:41 am

Marfy, great job done on this post. He was a colorful person. One correction. Elizabeth Arnwine Carrell Warford, his second wife, is the widow of Daniel Carrell. Another interesting thing is Rachel Margaret is a name given to a family member in the Daniel Carrell who married Keturah Burd family Bible. She was the second child of this couple born March 14, 1846. This Daniel is the youngest son of Daniel and Elizabeth Arnwine Carroll born March 6, 1815. He was 2 when his father died. Spelling of Carroll was later changed to Carrell. Daniel II had to go to court to get his orphan inheritance from the then husband of his mother Elizabeth. I have the document. These are my grandparents.

Marfy Goodspeed

May 1, 2015 @ 9:48 am

Thanks, Susan. I was aware of Elizabeth Arnwine’s first marriage, but left it out as it would have opened a whole new storyline. You can see what I’ve written about this family by going to “Families” and clicking on “Carrell”.

Ruth Hindleu

May 1, 2015 @ 11:19 pm

Hi, thanks for the great in on the Watford family. James & Rachel Cain Wardord were my great… grands ;-) so now I know more abouty great….uncle’s family.

Ruth

Virginia Johnson

May 9, 2015 @ 6:25 pm

When the Cornell map was drawn in 1851 the schoolhouse was on the Raritan Township side of 579. Bush attended there when it was in Raritan Township. Sometime after that the school needed to be rebuilt, so they moved it across the road. At some point the name was became official as the Croton School. Today it is a cute little yellow house used as a private residence.

Sheila Moore

May 11, 2015 @ 5:12 pm

Hello Virginia, I realize this is a long shot but just thought it couldn’t hurt to ask. My husband Richard H. Moore is a descendant of David and Permelia Johnson Moore (1800’s). We recently discovered the family bible which lists so many family members. Are you possibly connected to her Johnson family, father John and mother Ann? Alternatively, my son’s wife had an Erin Johnson family who migrated to Illinois. Any knowledge of him at all? We know that

David and Permelia as well as many other Moore’s are buried at the Sandbrook church cemetery.

Thank you.

Sharon Moore Colquhoun

June 20, 2015 @ 10:27 am

Hi,

Please see my reply on the original message. David and Permelia are part of my family as David is my third cousin, 3x removed.

Ron Warrick

June 11, 2015 @ 9:08 pm

Very interesting. Some of this may help me trace my 6g-grandfather, who was a contemporary of Elisha Warford. He named one of his sons Warford. Since he doesn’t seem to have owned property until later in life in New York, perhaps he was one of Warford’s “undistressed” honest tenents for a time.

Sharon Moore Colquhoun

June 20, 2015 @ 10:27 am

Hi, Sheila Moore! Your David Moore (married to Permelia Johnson) is my third cousin, 3x removed. Yes, they’re buried in Sand Brook. Have you ever been there? As far as I know, David’s parents were Hiram Moore and Amanda Holcombe. Although I have lots of Holcombe ancestors, I don’t have any more info than the names of the parents. I don’t have Ann’s surname. I’d love to know what’s in your Bible!

Rick Moore

September 26, 2015 @ 1:57 pm

Hi Sharon! I’m Sheila’s son. I’ve been doing a lot of research on our Moore ancestors over the past several months. We have been to Sand Brook cemetery and the family burying ground. I really enjoyed visiting them.

It’s my best guess that Permelia’s father and mother we’re John Johnson and either Mary Anne or Ann. I think John married Ann after Mary Anne passed away. I think Permelia had a half brother named James who moved to Delaware.

If David M. was your third cousin 3x removed, I think it means that our common great grandfather is Daniel Moore. That wouldn’t surprise me since he had 20 children. I’d be curious to know your Moore pedigree and any other info you have on our ancestors.

Please email me at rickymoore44@gmail.com if you’d like to connect. We know very little about our Moore ancestors beyond David M. I can also provide you a transcript and pictures of David and Permelia’s bible pages.

larry hill

September 20, 2015 @ 10:09 am

I wrote a book on the Warford family in the 199o’s. Elisha also had an unmarried son, Mahlon Warford 1818-1871. Elisha had bros. Elijah and David. Elijah had: Amelia, Holcombe and Theodore. Elisha’s mother, Rachel Cain, was daughter of Walter & Mary Ann (Hall) Cain. His aunt, Rachel Warford, m his uncle, Daniel Cain. Rachel Colvin who d 1853 Baltimore, MD was their cousin, through her mother (Cain).