Epilogue

The story of Little Jim is not quite over.1 There was the execution itself in Flemington, and then the aftermath, the way people processed these disturbing events. The court’s decision was so controversial it turned up in a modern U. S. Supreme Court case.

In the Courts

The previous article in this series brought up the issue of treating a child as an adult in a criminal case. This was, in fact, the law in the 19th century. And even in the 20th century, very little progress had been made. Not until 1954 did the NJ Supreme Court decide that a child under the age of 16 could not be tried in a regular court for a serious crime.

In December 1966, in the case of “In re Gault,” the U. S. Supreme Court ruled that juvenile defendants must be allowed “the constitutional right to due process of law” even in juvenile court. One of the dissenters was Justice Potter Stewart. His concern was that criminal trials were not appropriate for a juvenile court, because “their object is correction of a condition, not conviction and punishment.” Stewart wrote:

. . . to impose the Court’s long catalog of requirements upon juvenile proceedings in every area of the country is to invite a long step backwards into the nineteenth century. In that era there were no juvenile proceedings, and a child was tried in a conventional criminal court with all the trappings of a conventional criminal trial. So it was that a 12-year-old boy named James Guild was tried in New Jersey for killing Catharine Beakes. [my emphasis] A jury found him guilty of murder, and he was sentenced to death by hanging. The sentence was executed. It was all very constitutional.2

It wasn’t until 1988 that the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the execution of a 15-year-old is cruel and unusual punishment (by a vote of 5-3). In 2005, it raised the age for execution to 18 (by a vote of 5-4).3

In the Legislature

On November 12, 1828, two months after the appeal of Little Jim’s conviction failed, this item appeared in The Fredonian, a New Brunswick newspaper, under the heading of “Legislature of NJ”: “The consideration of the bill concerning James Guild, a coloured boy, convicted of murder, was resumed, the first section disagreed to, and the bill dismissed.” No mention of what was in the bill or who introduced it.

However, a query to the New Jersey State Law Library turned up the Minutes of the New Jersey State Assembly for 1828, and this item for November 4th (p. 17):

Mr. Potts presented the petition of the counsel of James Guild, a black boy, convicted of murder, in Hunterdon county, and under sentence of death for said offence; and also the petition of sundry other persons of said county; together praying, for divers reasons given, that the punishment of death may not be inflicted on said boy, but that it may be commuted into banishment, imprisonment for life, or foreign slavery.

This item answered the question I raised in part two—what was the motive of the four attorneys for taking on the defense of a person who would never be able to pay them. It appears that did it because of a principle, a consciousness that the death penalty would be entirely inappropriate for a 12-year-old boy. And they were not alone, as the bill was urged by “sundry other persons.” So, at the last minute, they turned to the legislature to save Jim’s life. Hats off to Messrs. Nathaniel Saxton, Peter I. Clark, Joseph W. Scott and Zachur Prall Esq.’s.

Unfortunately, according to the Assembly Minutes for November 6 (p. 62), “The bill entitled, An act concerning James Guild, a coloured boy, convicted of the crime of murder, Was read a second time, and postponed.” Apparently it was taken up sometime before Nov. 12th when the Freedonian reported that it had been dismissed.

As for the alternatives proposed for Little Jim, they were not gentle. Banishment seems odd, imprisonment for life is more in line with today’s thinking, but “foreign slavery” is inhuman. Certainly not much of an improvement over hanging.

The Execution

The execution of James Guild by hanging took place on November 28, 1828. Various sources describe the location as: “. . . in a field about 40 rods W. of the village, on the N. side of the road to Centre Bridge”;4 or “in a field west of the village of Flemington, near the road to Centre Bridge.”5 The clearest description stated that it took place on

“a scaffold near where the Reading Academy was later built; An empty field back then, the Reading Academy was later built there and was Flemington’s only public school from 1862-1915 ; the site is now the Bonnell Street entrance of the Reading-Fleming Intermediate School.6

Another matter that the sources agreed on was that there was a large crowd in attendance. But nothing in these sources mentions how Jim comported himself. Did he finally realize that all his posturing was for naught? Did this large crowd cheer when it happened, or was there a moment of silence? I suspect, judging from the bill proposed to the legislature, that there were many in the audience who understood that this was wrong. And the sight of a small boy hanging from the scaffold must have had a sobering effect on those who were feeling vindictive. Judging by the way his body was treated after the execution, I suspect there was more than a little uneasiness about the whole matter.

After the Execution

Jim was not allowed to rest in peace. Quite the contrary. There are even more stories about what happened afterwards than there were about the execution itself. I shall begin with the least gruesome, a version related by Frank Burd:7

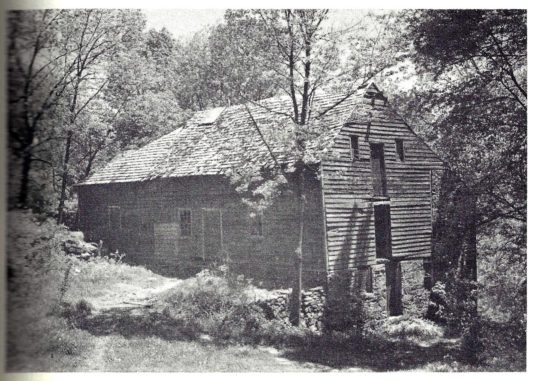

. . . his body was carted off in a spring wagon to Runk’s Mill, in what is now Idell, where by the light of a lantern, Dr. Coryell, proceeded to cut the little fellow up, just what he expected to find I never found out.

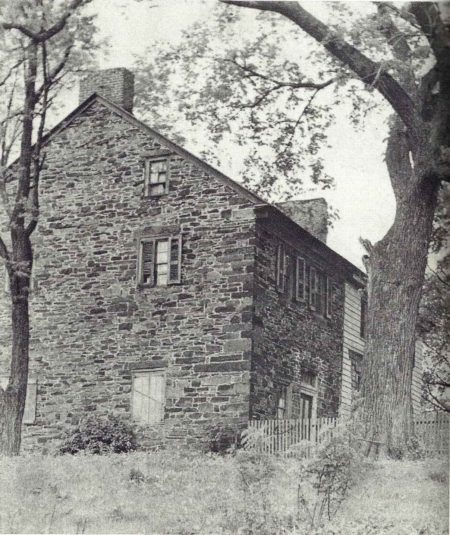

According to the Raritan Twp. Bicentennial booklet, “Dr. Israel Coriell, who boarded with the mill owner, claimed the body for scientific study.” I suspect the body was kept in the mill building, not in the house. Let’s take a closer look at Runk’s Mill and Dr. Coriell.

Runk’s Mill was owned by Samuel Runk who was present in the village of Milltown (Idell) for several years before the Revolution. By 1828, his son John (1791-1872) was running the mill for him. John also happened to be one of the Hunterdon County Freeholders at the time of the execution, so it is more than likely he was present to see it. John Runk became Hunterdon County Sheriff in 1836.8

Runk’s boarder at the mill property, Dr. Israel Lindsley Coriell, was born in Basking Ridge in 1799. During his short life, he became a highly regarded physician in Hunterdon County. He was a political ally of his landlord John Runk in the “party of the Administration,” i.e., of Pres. John Quincy Adams. In 1828, Coriell, Runk and John Waterhouse, Jr. were named to a committee to draft resolutions “expressive of the sentiments” of those attending the Administration Meeting in Kingwood. Runk and Coriell, together with John Cowdrick were also named to a committee to draft resolutions for a meeting held in Kingwood in support of the proposed Delaware & Raritan Canal.

When a fourth of July celebration was held in Lambertville in 1828, Dr. Coriell was appointed President of the gathering, which was certainly an indication of the high regard in which he was held. Later in October, he was present at a meeting at the House of James Kugler in Kingwood to support President Adams in the election that year.

Why Dr. Coriell thought he would learn something about human behavior by dissecting James Guild’s body is not easy to answer. It does reflect on the primitive state of medicine at the time.

Arrangements were made to transport the body of Little Jim to Runk’s Mill. A wagon was hired and a driver found, but his name is not known. His was not an enviable job. According to Frank Burd:

The story is told that on the way to Runk’s Mill, the driver of the wagon stopped at the tavern in Sergeantsville, presumably for a nip to steady his nerves a little. While he was inside some boys from around the neighborhood, being curious, of course, lifted up one corner of the canvas which had been thrown over the corpse to see what he looked like. What they saw nearly scared them out of a year’s growth.

Let’s just say that hanging does not improve one’s facial features. I gather that Mr. Burd picked up this story from word of mouth. There is some thought that Dr. Coriell never carried out the autopsy.

As for what happened to the body after it was taken to Runks Mill, the legends and superstitious notions are many. For instance, Dr. Coriell’s very promising career was brought to an abrupt halt by his sudden death in August, 1829. There were more than a few who thought it was some kind of retribution. Here is his obituary in the Hunterdon Gazette of August 12, 1829:

MELANCHOLY ACCIDENT. – Doctor Israel L. Coriell, of Kingwood, was killed on Saturday, by the upsetting of his sulkey, on the road about a mile below the Kingwood meeting house; he was found dead in the road, with the sulkey overturned and lying upon his head, and the horse standing quietly near him. His death was doubtless occasioned by the injury received in the head and neck. Dr. Coriell was from Basking Ridge – he has resided several years in Kingwood, and had obtained considerable business in the line of his profession. He was a useful citizen, generous in his disposition, polite and affable in his deportment, unaffected in his friendship.

There were several stories of Jim’s body being misused, most involving the placing of the body either on someone’s front porch or leaning out of an upper story window. Needless to say, if and wherever this happened, the neighbors were disturbed and insisted that the body be buried. But information as to where it was buried has not survived the years.

Wherever it was, people seemed to think that Little Jim would not rest easy until he had frightened the community out of its wits. According to Frank Burd:

After the hanging there were a lot of yarns and myths that grew up concerning little Jim’s ghost. I forget all the details but one was that his spirit, for some reason, was supposed to haunt the area around Pittstown much to the discomfiture of the Pittstowners.

That is odd, since Pittstown is not at all close to Runk’s mill. It was also said that Jim’s spirit “was subsequently seen on bridges and roads from Flemington to Goat Hill.”9 I am a little surprised that I found no stories of hauntings in the neighborhood of Bonnell Street where the hanging took place. As Mr. Burd wrote: “It was, of course, all a lot of poppycock but it made something to talk about on the long winter evenings.”

The Burial of Catharine Beakes

Despite the fact that her husband Samuel Beakes and his first wife Hannah were buried in the Pennington cemetery, there is no headstone for Catharine, there or anywhere else in the area. One might expect her to be buried next to her husband, especially since he had died only two months before she did. I hope that this neglect was not the result of ghoulish people digging her body up or of shame on the part of her family for the way she died. Her only surviving relative was her son Jonathan Vankirk, but little is known of him after this time.

The fact that the graves of both Catharine Beakes and her murderer, James Guild, have been consigned to oblivion speaks volumes to me of the tragedy of both their lives.

This has been a long, sad story. But it tells us much about how people behaved in 1828, what their ideas about crime and punishment were, and how superstitious some of them were. They were living in a different time, but really, they were not very different from us.

Some Sources

Although I consulted many sources for these articles, I suspect that there are still some versions of the event that I have not discovered. It seemed to me that since this story got repeated so often, it made sense to list the versions I did find, along with some relevant sources.

“An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery” (15 February 1804), electronically transcribed text of act of the New Jersey State Legislature published by the New Jersey Digital Legal Library (hosted by Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey).

Hubert G. Schmidt, “Slavery and Attitudes on Slavery in Hunterdon County, New Jersey,” pamphlet published by the Hunterdon County Historical Society, 1941.

Hunterdon Gazette, 1828. Brief notices concerning the trial. Also, articles on the recently destroyed courthouse and its rebuilding.

New Jersey Supreme Court, September Term 1828, “State V. Guild,” pp. 163-190.

Gordon’s Gazetteer of the State of NJ, 1834, pp. 68-73. Description of the NJ court system.

Barber & Howe, Historical Collections of the State of NJ, 1845, p. 253. The name was mistakenly given as James Bunn, age 14.

Hunterdon Republican, Jan. 2, 1879, Article on “Homicides and Hangings.” James Guild was properly named, but the age given was 14 rather than 12.

Trenton Evening Times, May 12, 1897. For “Talk of the Town; Somewhat Concerning a Distinguished Trentonian—Col. Wm. Halstead.”

The First 300 Years of Hunterdon County, page 21, and the 2014 update.

Hunterdon Historical Newsletter, Fall-Spring 1978, “Our Courthouse.” A three-part series with information about the time when James Guild was imprisoned in the Flemington jail, along with Frank Burd’s recollection of the Guild story.

“Raritan Township Flemington & Environs, A Pictorial & Narrative History,” Raritan Twp. Bicentennial Committee, 1976, p. 23, “The Story of ‘Little Jim.’” [no author listed].

Phyllis D’Autrechy & Roxanne Carkhuff, Some Records of Old Hunterdon County, p. 143, “Slavery in Hunterdon County.”

D’Autrechy, Phyllis, More Records of Old Hunterdon County, vols. 1 and vol. 2.

James P. Snell, History of Hunterdon and Somerset Counties, 1881.

John W. Lequear, Traditions of our Ancestors, pp. 75-80.

Footnotes:

- Little Jim, part one and two. ↩

- “In re Gault, Dec. 1966, p. 79-80, including footnote 2. For the entire opinion see In re Gault. I first learned of this reference to the Guild trial in the booklet “Raritan Township Flemington & Environs, A Pictorial & Narrative History,” Raritan Twp. Bicentennial Committee, 1976, p. 23, “The Story of ‘Little Jim.’” (no author identified). ↩

- Thanks to Dick Zimmer for this information. ↩

- Barber & Howe, Historical Collections of the State of New Jersey, 1845, p. 253. ↩

- James P. Snell’s History of Hunterdon County, p. 200. ↩

- From the 2014 update to First 300 Years of Hunterdon County, p. 21. ↩

- In Hunterdon Historical Newsletter, Fall 1978, p. 265. ↩

- There is much more to say about Hon. John Runk, but it will have to wait for another time. For more information see Kingwood Township of Yesterday by Barbara and Alexander Farnham, 1988. Thanks to Dennis Bertland for alerting me to this information. ↩

- From “Raritan Township Flemington & Environs.” ↩