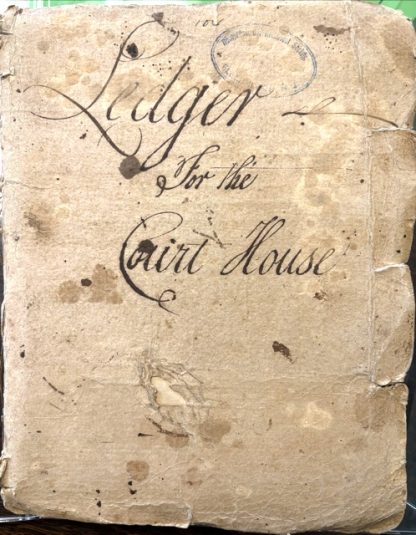

PART 3 of THE COUNTY HOUSE

During the years 1791-1793, a new courthouse for Hunterdon County was constructed in Flemington. Before it was finished, a complication emerged that connected the courthouse lot with Alexander’s tavern on Main Street.

Construction began after June 1, 1791, when a large gathering took place in Flemington to celebrate. The event was reported on June 22, 1791 in The Gazette of United States.1

This day the High Sheriff of the county assisted by the managers, viz. Mrssrs, William Chamberlin, Thomas Stout Esq. and Joseph Atkinson, and a very great number of inhabitants from all parts of the country assembled on the occasion–with sentiments of real joy, laid the first stone of Hunterdon county court House, appointed by law to be erected in this town : M. James Alexander [wrong, it was George Alexander] generously made a donation of the ground to the public to establish this much desired building–and the following is a copy of the inscription on the foundation stone.

IN THE YEAR OF CHRIST,

1791

GEORGE WASHINGTON,

PRESIDENT

of the United States of

AMERICA :

Happily ruling with the esteem of

ALL MEN,

WILLIAM PATERSON, Esq.

GOVERNOR

OF THE STATE OF

NEW JERSEY.

With the concurrence of the

Council and Assembly,

And the unanimous voice of the free citizens of

HUNTERDON COUNTY,

Have generously founded this

BUILDING,

For the administration of justice, the

Protection of innocence, and

Upholding the rights of mankind.JAMES KINSEY, ESQ.

Chief Judge,

ISAAC SMITH and JOHN CHETWOOD, Esq’s.Associate Judges

JOSEPH BLOOMFIELD ESQ.

Attorney-General.

ELISHA BOUDINOT, Es. Clerk

Of the Circuits.

JOSEPH READING, Esq. one of the Justices

Of the Court of Common Pleas.

SAMUEL W. STOCKTON, Clerk of the Court.

WILLIAM LOWREY, Esq. Sheriff.May the Almighty God prosper

This undertaking,

and influence the hearts of all ruling with

mercy, justice and equity,

And bless

the inhabitants of

HUNTERDON COUNTY.

The county sheriff and the managers were present for this event. The notables listed on the foundation stone were not. The expression that the President and Governor had “generously founded” the building, along with the Council, Assembly and “unanimous voice of the free citizens of Hunterdon County,” is an interesting way to describe how the courthouse came to be in that location. But then, the country was still quite young (Washington had been President for less than two years) and still sorting out the process of governing itself.

It would be almost two more years before meetings would take place in the new courthouse.

In the meantime, the Hunterdon County Freeholders held their meetings in Meldrum’s Tavern in Ringoes. That tavern seemed to suit the Freeholders better than other Hunterdon taverns, including the only one left in Flemington, the one operated by George Alexander. I suspect the Freeholders did not meet there because it was not big enough. Back in 1775 when its owner advertised it for sale, he described the house as three rooms “well finished.” That is a modest size for a house, and a small size for a tavern, especially if you needed enough space to accommodate 34 people, i.e., the Judges, Justices of the Peace and two Freeholders for each of the ten townships in the county.

There had been three taverns in the town in 1777, but it appears that the tavern on the north end of town run by Cornelius Waldron and the one that later became the Union Hotel, owned by Joseph Mattison, were not open for business in the late 1790s. This would explain the ambitions of Joseph Atkinson.

The Atkinson Hotel

In early 1792, Joseph Atkinson, one of the managers of the courthouse construction, was building “a new House.”

(Note: In the 18th and early 19th centuries, when documents refer to someone’s House they generally do not mean an ordinary dwelling. If it is a dwelling, that’s what it’s called. If it was a House, then it was most likely a public inn or tavern.)

We know of Atkinson’s project from a letter written by Isaac Passand to an unnamed recipient on May 4, 1792.2 Isaac Matthew Passand (1780-1826) was an English immigrant who may have come to Flemington with other prominent English immigrants like Thomas Lowrey and Thomas Capner. Passand owned a large tract of land bordering Alexander’s tavern lot on the west.

The letter from Passand is not easy to read. Here is Dennis Bertland’s transcript, with original spelling:

“Mr. Atkinson has finishd, his new House, that he was building wen you left us & has let it for £50 a year. It is as compleat an In as aney in the countrey — theres a great many well finishd, lodging Rooms in it & all made private – there is too roas of them – the length of the building & a passage betwixt – were the Doores, that have Locks & are numbered open into – . . .

there is to be Cort . . . will Commence on the 1 or 2 of May, so there will be thronging at this new Tavern [my emphasis], which made it needful for this Anderson who has taken it – to Com and lay in a stock of the best wine & porter that Philadelphia could afford.”

Mr. Anderson has not been identified. However, what impressed Bertland was the description of the hotel, with its private numbered rooms along a passageway, with doors that could lock, a real innovation for the time. It seems possible that the tavern was located near Elnathan Moore’s tavern of 1818, at the point where Flemington’s Main Street divides into North Main and East Main.

The type of “thronging” Atkinson was thinking of was described by Kathleen J. Schreiner when she wrote about the history of the courthouse: “In these days, the court sessions often had a carnival atmosphere, and laws had to be passed outlawing gaming, horseracing and cock-fighting near the courthouse.”3

Aside from the carnival-type activities, many visitors from distant parts of the county would need a place to stay for a day or two while their business was transacted with the court, county clerk or the Freeholders. They might stay at George Alexander’s inn (in contemporary records, George Alexander was identified as an innkeeper rather than a tavernkeeper). But Atkinson probably thought that Alexander’s inn would not meet the new demand.

Joseph Atkinson, born about 1744, was the son of Thomas Atkinson & Hannah Doddridge of Kingwood. He married three times. His first wife, Jemima Prall (c.1743-1783), was the daughter of Aaron Prall & Margaret Whitaker of Amwell. Their son was Asher Atkinson (1770-1857) who married Agnes Mattison (1778-1863).

Joseph Atkinson married second, at the Quaker Meeting in Philadelphia, Susanna Rakestraw (1757-1792). His third marriage was to Sarah Alexander (c.1770-1844), daughter of tavern-owner George Alexander & Mary Fleming. That marriage took place about the time that Atkinson was appointed one of the courthouse managers.4

Balancing the Books

As one of the three men appointed by the Freeholders to manage the courthouse construction, Joseph Atkinson kept the books and reported on expenses to the Freeholders.5

As one of the three men appointed by the Freeholders to manage the courthouse construction, Joseph Atkinson kept the books and reported on expenses to the Freeholders.5

I cannot say what role the other two managers, Freeholder William Chamberlin and Thomas Stout, Esq., played in the courthouse construction.

This first courthouse was not the masonry building with pillars we see today. It was built of boards, shingles and stone (no doubt for the foundation). Materials hauled to the site included sand, lime, stone, boards and shingles. Other items on Atkinson’s ledger were nails, glue, lime, sand, timber, brick, a cord of wood, and 117 feet of inch & a half plank.

A partial list of purchases includes paint, window weights, a broom, white lead, “Spanish brown,” oil, a quire of paper. Also, a pint of spirits, bacon, veal, butter, 2 gal. spirits, rum, more bacon, rye flour,

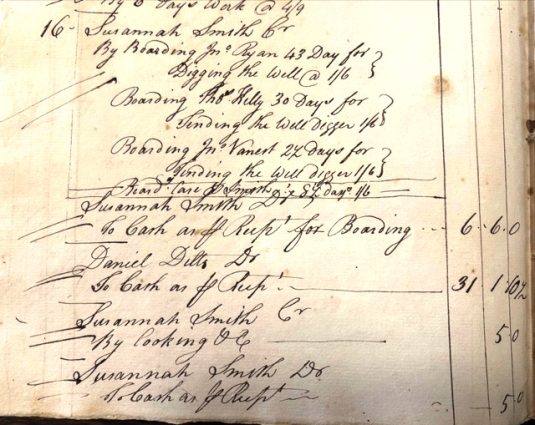

Services provided were boating, portage, carting, hauling, iron work, digging the well, masonry, carpentry and turning the bannisters.6

Atkinson paid the workers on a more or less weekly basis. He sometimes paid workers in “hard cash” and sometimes in “paper.” The amounts paid were in pounds, shillings & pence, not in dollars and cents. It was not until after 1800 that the English currency was discontinued.

One of people paid for their services was Susanna Smith. According to Atkinson’s accounts, in 1791, Smith provided boarding for certain workers, i.e., 43 days for Jno Ryan who was digging the well, 30 days for Thomas Kelly and 27 days for Jno Vanest for ‘sending’ [?] the well digger. She was paid “three pounds paper currency for Boarding David Thomas” and for “washing & Scrubbing Court House &c &c in Fleming town.” She was also paid for cooking and cleaning.

Atkinson’s final account for August 1792 listed a total payment to Susanna Smith of £10.18.3, in both cash and paper. She was the only person on Atkinson’s list to provide boarding, cleaning and cooking.

Atkinson’s final account for August 1792 listed a total payment to Susanna Smith of £10.18.3, in both cash and paper. She was the only person on Atkinson’s list to provide boarding, cleaning and cooking.

A Legal Surprise

Returning to the Freeholders’ meeting at Meldrum’s Tavern on August 27, 1792:

The Minutes of the last meeting having been Read over, the Moderator laid a Letter before the Board from Samuel R. Stewart attorney for Susanna Smith, who claimed a Right of Dower in the Lot of Land whereon the Court House & goal & yard is Erected in Flemington and gave it as his Oppinion [sic], that the Claim is well founded in Law, and suggested to the board that they would make the widow an offer, of such Sum as they may think Reasonable.7

I have puzzled over how to present this story. It requires a certain amount of speculation, and I worry that readers might assume that I have proven all of what I am about to write, when I have not. But I really like my theory, so here goes:

Susanna Smith was the lady who had been boarding, cooking and cleaning for the courthouse construction workers. Why did she have a right of dower in the courthouse property? Because she was the widow of the former owner, the absconding Loyalist Joseph Smith. (See Part One for his story.)

The timing of Susanna’s claim is curious. Did it mean that she had just gotten word that husband Joseph had died? There is no record of him after he left in December 1776, and the Freeholder Minutes say nothing about him. We do not know what happened to either Susanna or Joseph during the sixteen years between 1776 when Joseph left to join the British and 1792.

Susanna Smith did not claim a right of dower when the Smith property, including what would become the courthouse lot, was sold to George Alexander in 1779. I thought perhaps it was because Joseph Smith had not yet died. But Leonard Lance informed me that because the Smith property had been seized by the Sheriff due to unpaid debts, “the government had clear title” to sell it. The only way Susannah could have “stymied the transfer from her husband” was to first pay the outstanding debt. If she did so, she would still have to go to court to get a declaration of death, which she did not do.

Even so, the Freeholders took her claim seriously. I suspect that it took an enterprising young attorney to encourage Susanna to make her claim–perhaps someone who perceived that the Smith property was far more valuable with a courthouse on it.

Samuel R. Stewart

Samuel Robert Stewart, the son of Irish immigrant and Revolutionary War Colonel, Charles Stewart and his wife Mary O. Johnson, was born at his parents’ home in Landsdown, in Kingwood (later Franklin) Township, on October 10, 1765.

He graduated from the College of New Jersey (Princeton) in 1786. The next year, he got an introduction to county bureaucracy when he acted as administrator for the estate of his older brother Charles Alexander Stewart, who had died at the age of 24 on August 1, 1785. (Administration of the estate was not granted until April 13, 1787. The other administrator was Aaron Dunham. Stewart’s father, Charles Stewart, acted as ‘fellowbondsman’ or surety.) This experience might have inspired Samuel to obtain a law degree; he was admitted to the Bar in 1790, the year that Flemington was chosen to be the site for the county courthouse.8

The Freeholders responded to Stewart’s letter by naming a committee to settle with Susanna Smith in exchange for her claim of a dower right. This was the practice for extinguishing a spouse’s rights of ownership in a particular property. As the Minutes report:

Whereupon [it was] ordered that John Gregg, Joseph Hankerson & Thomas Reading, Esq’r do wait on the widow Smith and settle her Right of Dower and take her Quit Claim for sd Lott of Land. — Also agreed to give them an order on the County Collector to draw any Sum of money that may be Sufficient for them to agree for the Quit Claim

And they are to make their report with the Quit Claim unto the Board of Justices and Freeholders at their next meeting.

This was just one of many items on the Freeholders’ agenda for August 27th, but it was the first one. The rest of the meeting was concerned with the amounts of money owed by the various townships to fill their quotas for funding the courthouse construction. Several were “in arrears.” The Freeholders also settled Meldrum’s bill of £10.11.3 for services rendered.

It took nearly a year for the Freeholders to resolve the issue with Susanna Smith. In the meantime, on May 8, 1793, the Board of Freeholders held their first meeting in the new courthouse.

Generally speaking, the Freeholders only met twice a year, in May and August, which was meant to accommodate the work demands of Hunterdon’s residents, most of whom were farmers. It also avoided the difficulty of traveling in winter. This is why the freeholders did not meet again until August.

The Settlement

At the Freeholders’ meeting on August 5, 1793, they settled with John Yard, black smith for “work done for the use of the gaol at Trenton” and with David Wrighter, gaoler, for candles, Cryer’s fees, etc.

(Note: The spelling of goal/gaol is discussed in Part Two. It is fairly ancient. The modern spelling of jail did not become common until the 19th century. The two spellings, goal & gaol, were both in use in official documents.)

Then the Freeholders turned their attention to the matter of Susanna Smith, as shown in the Freeholder Minutes for this date (with original spelling, but paragraph breaks added):

John Greeg and Joseph Hankenson, two of the Commite appointed by the Board at their meeting the 27th of August 1792 to agree with Susanna Smith for her Right of Dower in the Lot of Land Whereon the Court House is Erected at Flemington reported that they had agreed with her for and in Consideration of the Sum of Four Pounds five Shillings & four Pence [£4.5.4]

And Produced her Quit Claim for said Lot of Land, with a Receipt from Jasper Smith Esq’r Attorney at Law for drawing sd Quit Claim amounting to Eight Shillings which said Report was agreed to —

And it was agreed by the board that John Gregg take Charge of the above said Quit Claim until further orders — by order of the Board [signed] John Lambert Clk.

John Gregg no doubt took charge of “the above said quit claim,” but he never bothered to record it. Normally, when a spouse conveys her dower right to a purchaser of her husband’s property, a deed is recorded. It is necessary if the purchaser wants to have a ‘clear title’ to that property. To my frustration, no deed from Susanna Smith or Samuel R. Stewart to the Freeholders was recorded. Neither was one for Smith or Stewart to George Alexander. Very unorthodox. But the Freeholders probably assumed that the courthouse lot would never be sold, so the matter of clear title was irrelevant.

Recording the Courthouse Deed

Another deed that had not yet been recorded was the original conveyance to the Freeholders by George Alexander. No action was taken until the Freeholders’ meeting for September 30, 1793.

The Managers Joseph Atkinson & Thomas Stout present the Deed for the Lot of Land whereon the Court House Gaol & Yard is Erected, which being Read over It was Approved and Ordered that the above said Committee take Charge thereof and get It Recorded by the Clerk of the County and to Return the same to the Board at their next Meeting for to be under the direction of the Board–by order of the Board. John Lambert, Clk.

It is a little odd that the deed presented to the Freeholders was two and a half years old. It had been signed on March 15, 1791, over a year before Smith made her claim. It appears that they were waiting for the construction to be finished, but I do not know why that was necessary.

Although the deed from George Alexander did finally get recorded, on Nov. 2, 1793, nothing in the Freeholder Minutes shows that the original deed was returned to the Board as specified in the meeting of Sept. 30, 1793.

Note: Snell wrote that even though the entire courthouse burned down on Feb. 13, 1828, “the county records were saved, the clerk, perceiving the imminent danger of their destruction, having removed them to a place of safety.” Imagine trying to do that today, with the huge amount of records in the County Clerk’s office. Impossible.

Snell did not write anything about whether the original foundation stone had been preserved. In fact, he did not write anything at all about the foundation stone.

Stewart, Smith & Alexander

While Susanna Smith’s claim for her dower right was under consideration, her attorney, Samuel R. Smith, was taking steps to become a Counsellor at Law, which happened in 1794. (To become a Counsellor at Law, Stewart had to be a licensed attorney for at least three years and take a second exam. This allowed him to appear before the State Supreme Court.)

And now I return to the realm of conjecture.

James P. Snell wrote that on October 16, 1795, Charles S. Stewart was born in Flemington to Samuel R. Stewart.9 Snell did not name the mother because Samuel R. Stewart was not married. It was not until two months before the birth of his second child, Robert S. Stewart on June 15, 1799 that he married his children’s mother. Her name was Anna Smith.

Who was Anna Smith? Her parentage is not provided in any record I have of her. But consider this: in order to have a child in 1795, she was probably born about 1775. That would make it possible for her to be the child of the absconding debtor Joseph Smith and of Sam’l R. Stewart’s client, Susannah Smith, widow of Joseph.10

Granted, Smith is a very common name. I have no proof for this theory, but it fits together too neatly to be ignored.

The Alexander Household

Recall that Joseph Smith abandoned his property in 1776. It seems likely that he also abandoned his wife, because Susanna was living on her own in Flemington in 1791. What happened to her after Joseph left? She must have remained in the house that Joseph built, unless someone evicted her. I suspect that did not happen.

A few months after Joseph Smith departed, George Alexander applied for a tavern license, but not for the one his father-in-law, Samuel Fleming, had run, because that year it was operated by Cornelius Waldron. Where else would Alexander have run a tavern? More than likely in the house that he purchased two years later, in 1779, the house that Joseph Smith built, where Susanna was probably living, perhaps with her young daughter.

George Alexander was the father of three children, the youngest of whom, Thomas, was born in 1775. His wife, Mary Fleming, may have died soon afterwards. There is no record of her death. In fact, there is no record of where she and George were buried. Which strongly suggests to me that they were buried with Mary’s parents, Samuel & Esther Fleming, whose burial location is also unknown.

If Mary died soon after giving birth to son Thomas, then George Alexander was a widower with three children in 1777 and Susanna Smith was an abandoned wife with a small daughter, living in the house that Alexander turned into a tavern. In the tax returns for 1784, there were eight people living on Alexander’s property, six of whom could have been George, Susanna and their children, (leaving two unaccounted for).

If in fact Susanna Smith did remain in George Alexander’s house with daughter Anna, then by 1791, Anna would have been old enough to help out in the tavern, and would have become acquainted with the tavern’s visitors, including the young attorney, Samuel R. Stewart, who probably came to discuss Susanna’s dower right. Anna would also have been able to assist her mother with the extra work of boarding, cooking and cleaning for courthouse construction workers.

All these ‘what if’s’ rely on the recorded fact that Anna Smith and Samuel R. Stewart were married on April 9, 1799 by Rev. Thomas Grant of the Flemington Presbyterian Church, which was located on a small lot near property acquired by Samuel R. Stewart in 1795.11

Why did the couple wait so long to marry? Consider this: Samuel’s father was the wealthy and well-known patriot, Col. Charles Stewart. Samuel was Charles’ only surviving son. Were Samuel to announce a marriage to the daughter of an absconding Loyalist, it might have caused his father great unhappiness and embarrassment.

On the other hand, there does not seem to have been any effort to conceal Samuel’s situation.12

There is a great deal more to say about Samuel R. Stewart and his father Charles. But I must postpone it for the next post.

Footnotes:

- HCHS Ms. Box for Courthouse records. Note on the back: “folder 980 / 24 inch shelves.” The frequent use of ‘f’ for ‘s’ makes it hard to read, so I have replaced the ‘f’s with ‘s’s. It also used ‘vix’ instead of ‘viz.’ Note: I had originally missed the note on the back of the page identifying the source. ↩

- The letter was found by Dennis Bertland in the Capner papers at the Hunterdon County Historical Society: HCHS, Capner Papers, Box 3, folder 89. ↩

- Hunterdon Historical Newsletter, Winter 1978, p.3-4. ↩

- There is nothing in Deats’ Marriages or NJA Marriages for Joseph Atkinson. ↩

- The notebooks Atkinson used for monitoring the expenses have been preserved and are kept at the Hunterdon County Historical Society. Ms. Collection, 3.002-0389 & 3.002-0391. ↩

- There is a surprisingly long list of people who contributed labor and /or services. A list of their names can be found in Kathleen J. Schreiner’s article on the Courthouse history. ↩

- Freeholder Minutes, August 27, 1792; also James P. Snell’s History of Hunterdon County, pp. 201-202. Much to my regret, that letter from S. R. Stewart to the Freeholders has not survived. ↩

- James P. Snell, History of Hunterdon County, 1881, p.207. There is no mention of Samuel R. Stewart in Snell’s section on “The Bench & Bar in Hunterdon County.” Contemporary lawyers were Jasper Smith, Richard Stockton, Lucius H. Stockton of Trenton, Richard Howell, Samuel Leake, Thomas P. Johnson, Geo. C. Maxwell. Also, Lucius W. Stockton. ↩

- Snell, p.207. ↩

- Find-a-Grave identifies the wife of Samuel R. Stewart and mother of Charles S. Stewart as Anna Gray Stewart, died 22 March 1806, burial location unknown. It does not explain where the name Gray comes from. I believe this is a mistake. ↩

- Vol. 1 p.31, Hunterdon County Marriage Records. ↩

- The Stewart family also mystified John W. Kuhl. See “Charles Samuel Stewart (1795-1870), Navy Chaplain,” by John W. Kuhl, Hunterdon Historical Newsletter, Spring 2009, Vol. 45, No.2, p.1059. ↩

Drew Pearce

January 22, 2026 @ 7:23 pm

Another well written and well researched post. Thank you!