In my previous post I wrote about the history of the Lambertville Iron Works, the company that constructed the Lockatong bridge. At that time, after several months of work and an initial bridge opening, the bridge was closed again in order to repair the repairs. It has since been reopened, and is definitely worth a visit. It is not exactly the bridge it used to be, but it has been beautifully restored, and all concerned should take pride in it.

So now to continue the story of the bridge and its builders:

After William Cowin

William Cowin, Director of the Lambertville Iron Works, was only 49 when he died in November 1874. His wife, Caroline Corson Welch, was determined to carry on the Iron Works, even though she was a 34-year-old widow with two small children (ages 9 and 7), and she had also to deal with the death of her mother, Mary Hannah Seabrook, the previous April.1 She may have been encouraged to hold on to the Iron Works by her father, the great engineer, Ashbel Welch, who was 65 years of age at the time, and living nearby.

In December, 1874, this notice appeared in the Hunterdon Republican:

Lambertville Iron Works. Since the death of William Cowin, the late proprietor of these works, arrangements have been made to continue the business in the name of Mrs. C. W. Cowin. The general Foundry and Machine business will be carried on, including the manufacture of Machinists’ Tools, Steam Engines, Iron Bridges {my emphasis}, Car Wheels, Railroad Work, Mill Work, etc. The establishment also has the right to manufacture and will keep on hand, the Eclipse Patent Sectional Safety Steam Boilers and Johnson’s Patent Universal Lathe Chuck. Circulars and prices will be furnished on application. By William Johnson, Manager.2

Note that Iron Bridges are listed among the products of the Iron Works. Note also that William Johnson had stepped in to act as manager of the company. The fact that Johnson was staying with the company probably convinced Caroline Cowin that she could carry on the business. Note also the reference to “the Eclipse Patent Sectional Safety Steam Boilers and Johnson’s Patent Universal Lathe Chuck.” No mention of Johnson’s earlier patent for ‘eccentrics’ on iron truss bridges (described in the previous article).3 William Johnson remained with the company during the 1870s. He was still there in 1880, when he was identified in the census as superintendent of Iron Works in Lambertville.

The Iron Works in the 1870s

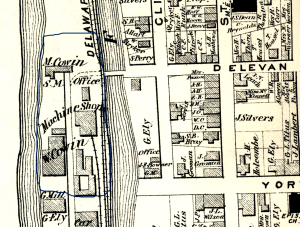

By 1873, the company had developed a significant infrastructure, as is shown in the Beers & Comstock Atlas of that year.4

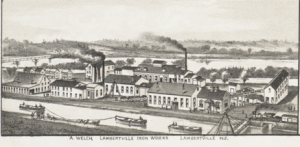

This map is fascinating because of all that is now missing. For instance, the map shows a bridge across the canal at Delavan Street. There is no such bridge today. Since Delavan Street was created in 1832, it seems likely that the street and the bridge had something to do with construction of the D&R Canal. The bridge led to a roadway that passed by the office and other buildings belonging to “W. Cowin.” This was the Lambertville Iron Works; why it should have been labeled W. Cowin instead of Lambertville Iron Works is a mystery to me. We can get a better view of the buildings from an aerial picture of Lambertville published ten years later, in 1883. The size of the plant appears to have expanded since 1873.

A visit to this site today will be disappointing. All that remains is the brick building, now vacant, once owned by the River Horse brewery. The Lambertville Master Plan of 2001 noted that the property was once the location of the Original Trenton Cracker Factory. Walking north from that building, all you find is a modern building, also vacant, with its parking lot, and beyond that a natural area with abandoned railroad tracks on the east. For sight-seers, the walk is worth it to see the highly decorated abandoned railroad car, a very colorful ruin.

Surviving the Panic of 1873

1873 was a notable year, because of “The Panic of 1873.” The country’s economic system went through one of those turbulent periods that survivors of 2008 will recognize. The end of the Civil War brought on a large dose of “irrational exuberance,” and a huge amount of investment was made in laying out railroad tracks. This investment came in large part from bonds that were purchased by ordinary workers and farmers, as well as loans from banks across the country and from Germany. Not only were railroad tracks being laid out, but large numbers of rail cars were being built by iron foundries like the Lambertville Iron Works.

But by 1873, money for railroad expansion was drying up, and Philadelphia investor Jay Cooke, who had been one of the driving forces in railroad investment, had to shut down his investment bank, which caused harsh ripple effects through the American economy. But there were also problems in Europe that fed into the crash, like the high cost of the Franco-Prussian War and Germany’s decision to stop minting silver coins, which mostly came from the United States. This hurt the U.S. economy, but so did the shrinkage of German investments in railroads.

So, banks began calling in loans, and stocks were sold to pay off those loans, causing the stock market to plummet. Deflation ensued and bankruptcy became widespread. Unemployment got as high as 25% and foreclosures became common. This Depression lasted for the whole decade. Hunterdon County felt the impact of the depression, just as the rest of the country did. Many people walked away from their homes, leaving them abandoned, and moved west looking for better employment opportunities, even though there were none there either.

Despite this disaster, or perhaps because of it, the Hunterdon Freeholders set about building bridges throughout the county. There are many requests for bids published in the local papers during the 1870s. Perhaps this was seen as a way to provide employment and stimulate the local economy. It would be interesting to see what impact all these bridges had on the tax structure during those years.

Hunterdon Bridges in the 1870s

On August 22, 1873, the freeholders published a notice that the contract for a bridge at Milford was being awarded to William Cowin of Lambertville Iron Works. And on August 11, 1874, the freeholders ordered a new bridge to be built over “Rio Grande” in Delaware township.5

In 1875, the freeholders supervised construction of a bridge at Riegelsville between Hunterdon and Warren Counties, a bridge on the South Branch of the Raritan between Clinton and Franklin Townships, and a bridge over the Neshanic by Kuhl’s Mills. In 1876, the new bridges were at Rockafellow and Ent’s Mills, at Hughesville between Warren and Hunterdon Counties, and one at “the Hook” in Lambertville.

1877 saw a continuation of work that had been begun in 1876, plus repairs to bridges damaged by bad weather. A new bridge was ordered to cross the South Branch at Chamberlain’s Mills and at Rowland’s Mills in Readington, also a bridge over the Musconetcong near Penwell. On October 25th, the Hunterdon Republican published the freeholders’ request for bids on two more bridges, one over the Capoolong Creek near Landsdown, and the other over the Lockatong in Delaware Township.

The Lambertville Iron Works obtained contracts for at least four of these bridges: the 1875 bridge over the Neshanic, the 1877 bridge near Chamberlain’s Mills, the 1877 bridge over the Capoolong and the one over the Lockatong.

The 1875 bridge over the Neshanic is interesting, as it was advertised to be partly cast iron and partly wrought iron, and would only cost $1,085.6 The bridge at Chamberlain’s Mills was meant to replace a covered bridge, which the freeholders offered for sale in the Hunterdon Republican on August 22, 1877.7 Work on the new bridge was awarded to Lambertville Iron Works on October 11, 1877.

The bridge over the Musconetcong presented an interesting situation. A bid was submitted by “Johnson & Co. of Lambertville” rather than the Lambertville Iron Works. The company bid $1300, but was outbid by the King Iron Bridge Co. of Cleveland, showing how competition for bridge building had increased significantly by this time. Other companies bidding were Kellogg & Morris of Pennsylvania, $1,215; Canton {Ohio} Bridge Co., $1,397.25 and Tupplett & Wood of Phillipsburg, $1,650.8 As for “Johnson & Co.,” this was the only reference I found in the Hunterdon Republican to that company name. Perhaps the writer meant the Lambertville Iron Works and knew that a reference to “Johnson & Co.” would be understood by his readers to mean the Lambertville Iron Works.

The Bridge Over the Lockatong

The Contract

The Hunterdon Republican reported on October 11, 1877 that a severe storm had crossed through Hunterdon County on October 4th, wiping out dams in Readington and at Mt. Airy, and flooding the streets of Lambertville.9

Oct 25, Hunterdon Republican, Local Affairs. The Board of Freeholders advertise in another column for proposals for a new iron bridge over the Capoolon Creek, near Landsdown Station, the bridge there having been carried away by the last freshet. The Board have also decided to build an iron bridge of 125 feet span over the Lackatong creek in Delaware township. This work is also made necessary by the flood a few weeks since.

As a result of the storm damage, James Callan of Lambertville and Jonathan M. Dilts of Delaware Township, two of the freeholders, called for the Board of Freeholders to examine a location where the bridge over the Lockatong had been “carried away by the recent high water.” This notice appeared in the Hunterdon Republican on November 1, 1877:

The Committee appointed by the Board of Chosen Freeholders of the county of Hunterdon for the erection of an Iron Bridge over the Lackatong Creek in the township of Delaware will receive proposals at the hotel of Sutton Hockenberry at Stockton for the erection of the said bridge, until Thursday, the 8th day of November, 1877, at 12 o’clock noon of said day.

The Bridge to be of all Wrought Iron, extreme length between abutments, one hundred and twenty-five (125) feet. The roadway to be sixteen (16) feet in the clear, planked with good White Oak Plank, 3 inches thick, clear of wane edge or sap. The Bridge to be built with a factor of four (4) for safety, proportioned to carry a distributive load of one hundred tons in addition to its own weight.

Signed: J. H. Boozer, J. M. Dilts, H. Lux, P. B. Goodfellow, J. Callen, B. Blackwell, Committee.

Despite the freeholders’ specifications, instead of being “all Wrought Iron,” the bridge that was built was part cast iron and part wrought iron, and that is one of the factors that makes it so important. The freeholders may have had a preference for wrought iron because it was flexible and strong, but it was also more expensive than cast iron. It appears that William Johnson managed to convince them he had a better plan, making use of both wrought iron and cast iron.

1877 Nov 22: “The Lambertville Iron Works have been awarded the contract for building two bridges in Hunterdon County,—one for $1,100 and one for $2,850. 10

As mentioned above, the Freeholders had advertised for bids on another bridge at the same time, “a new iron bridge” over the Capoolong. Lambertville Iron Works got both contracts. Johnson’s bid for the Capoolong bridge, only $1100, was much lower than for the Lockatong bridge, which suggests to me that if LIW did build a bridge there, it was not the one standing there today. The Historic Bridges website gives the credit for building that bridge to the Phoenix Bridge Co., and dates it to 1885. The Landsdown bridge is the only bridge over the Capoolong that is documented on their website.11

The Freeholders must have been satisfied with the work that Johnson did on the Neshanic and other bridges. Be that as it may, they pretty consistently chose a company that submitted the lowest bid. Although it must have been a challenge to produce quality work and still offer the lowest bid, it is clear that William Johnson built very good bridges. I imagine he did not use the technique that an unknown bridge building company used on a bridge at Locktown. Here is a report from 1873:

Accident. On 21 Sept. 1873, Andrew Bellis was going to church in Locktown in the evening, when he ran into a ditch in the road near that town. The ditch had been dug across the road for the purpose of putting up a bridge. His buggy was upset and he escaped with only a few scratches. When men dig ditches or pile up stones in the highway, they should put up some warning signs or post guards at night.12

Construction of the Bridge

Construction on the Lockatong Bridge probably began not long after the contract was awarded.13 The freeholders’ minutes for November 14, 1877 show that $1,697.65 was allotted to Delaware Township for bridge expenses.14

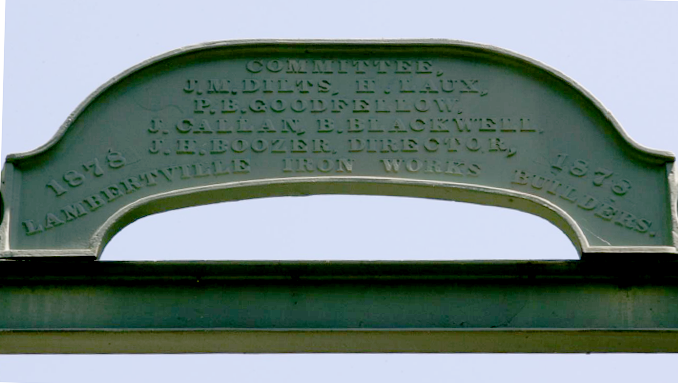

As we now know, in 1877-78, the Lambertville Iron Works was managed by William Johnson, and it is really to him that we owe thanks for this marvelous bridge. And it should also be pointed out that the owner of the company was a woman, Mrs. Caroline W. Cowin, widow of William Cowin and daughter of Ashbel Welch. As for who got credit for the bridge, the freeholders took top billing. Here is the sign that was erected over the top chord or cross-piece:

COMMITTEE,

J.M.DILTS, H. LAUX,

P.B. GOODFELLOW,

J. CALLAN, B. BLACKWELL

J.H. BOOZER, DIRECTOR,

1878 LAMBERTVILLE IRON WORKS BUILDERS. 1878

If I had my druthers, the sign on the bridge would include the names of Mrs. Caroline W. Cowin and William Johnson.

The “Committee” was the committee of freeholders assigned the job of overseeing the construction. J. H. Boozer was the Freeholder Director in 1877 when the contract was awarded. The other freeholders were Preston B. Goodfellow and James Callan, of Lambertville, Jonathan M. Dilts of Delaware Twp., Henry Loux of Frenchtown and Bloomfield Blackwell of West Amwell.

No doubt the name of the Freeholder Director, Joseph H. Boozer, has caught your attention. It did mine also, so I’ve researched him and his family. But his history is being saved for a separate article. He was present in Lambertville in 1860, age 26, and working as a clerk. He quickly rose to prominence in Lambertville, being elected mayor in 1871, and as freeholder from Lambertville in 1875.

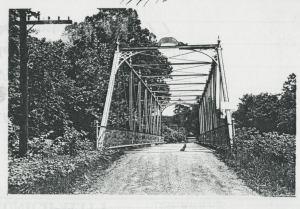

Outstanding Characteristics

It takes only one glance to see that this is an unusual, and unusually lovely, bridge. But there is more than beauty under its skin of green paint. It is outstanding because it was built by a local company making use of wrought iron for compression and cast iron for fastenings as well as decorative elements, and because it is the oldest bridge still in use in the United States that has its original Phoenix columns. And it was constructed as “a pre-fabricated metal truss bridge,” meaning that it could be taken apart and put back together, a blessing for the company recently hired by the Hunterdon freeholders to do the restoration work.15

The bridge is known by engineers as a nine-panel, pin-connected, Pratt through-truss bridge. It is one of the few bridges in Hunterdon built with material from the Phoenix Iron Works Company of Phoenixville, PA, and probably the earliest still in use.

Truss bridges were being built for hundreds of years because builders had discovered that triangles were a lot stronger than rectangles. When a heavy load passes over one of these bridges, the diagonals actually stretch and then return to shape afterwards. Early truss bridges were made of wood, which has the needed flexibility for compression. It also has the strength to resist tension, but as the years went on, wood became more expensive. The problem was solved in the 1840s when iron came into use. With that break-through, engineers rushed to design new types of truss bridges, all of them variations on the triangle, using diagonals and vertical posts, and top and bottom chords, or beams, to hold them together. One of those designs was the Howe truss using iron rods for vertical posts, and wood for for diagonal beams. An example of this can be seen today in the Green Sergeants Covered Bridge.

One of the early bridge designers in America was Caleb Pratt, whose truss bridge design was patented in 1844. It became a very popular because it could make use of iron for both tension and compression, and by the 1850s, iron was becoming much more affordable. The Lockatong bridge is called a “through truss” because the sides are joined at the top, obliging travelers to pass through the bridge rather than simply over it, the way one does on a “pony-truss” bridge.16

Phoenix Columns

Cast iron was easier to use for large items because it was made by heating the iron to a liquid state and then pouring it into molds. One of its shortcomings was that it was so brittle it could not be riveted. On the other hand, wrought iron had to be worked into desired shapes by heating iron until it was malleable.

Making the diagonals for a truss bridge out of wrought iron was preferable because it was flexible and could handle compression, but finding a way to do that economically was a challenge until the Phoenix Column was invented by Steven Reeves on June 17, 1862.17 Phoenix columns became very popular for building bridges and large buildings, but it only took a few years before wrought iron was replaced with steel. The Raven Rock Road bridge is one of the very few that still has its original wrought iron Phoenix columns.

According to A. G. Lichtenstein, “the genius of the Phoenix section is that it is stronger and more economical than its cast-iron counterpart and not prone to failure in compression.” 18 Cast iron was used to join the sections of wrought iron together in the Phoenix columns, and also used for the many decorative elements, like the ornate brackets and the finials. Thanks to its location on a lightly traveled road, the bridge has survived for 136 years, retaining features that soon went out of fashion. About ten years after it was built, the Phoenix Iron Works shifted production to steel, which became the preferred material from then on.19

The Phoenix Iron Works

This company, located in Phoenixville, Chester Co., Pennsylvania, has a long history. It was founded in 1790 as a nail factory by Benjamin Longstreath.20 This is one of those serendipitous moments that come along while doing research. Benjamin Longstreath was a miller who lived at Raven Rock from 1804 to 1806. He was probably in Hunterdon County earlier than that because he married Isabella Dennis here in 1801, and the marriage was performed by John Lambert Esq., acting as Justice of the Peace.21 Isabella Dennis was the daughter of Lambert’s second wife Hannah Dennis. So, it appears that Longstreath had sold his nail factory sometime before 1804.

In the 1820s, the factory was taken over by David and Benjamin Reeves, and James and Joseph Whitaker, creating a company known as Reeves & Whitaker. At first the company produced pig iron and wrought iron, but by 1825 it had expanded its plant to include furnaces powered by steam made from anthracite coal. In 1855, with its work focused on iron products for the railroads and structural beams, the company was renamed The Phoenix Iron Company.

By the time of the Civil War, the company had expanded enough to be a major supplier of cannon to the Union Army. In 1862, one of its owners, Samuel Reeves, patented the Phoenix Column, which became the company’s most successful product. You can learn more about the bridge on the website Historic Bridges.org where you can also see a nice photo of the bridge without its new guide rails. The site provides plenty of interesting information on the Phoenix Iron Co., manufacturers of the Phoenix columns.

Building the Bridge

I am now going to venture into the realm of speculation. There is no journal or news article that describes how the bridge was built. So I will use my imagination—take it for what it’s worth. The Lambertville Iron Works no doubt ordered the Phoenix Columns from the Phoenix Iron Works. We know that the Phoenix Iron Works produced the columns because they stamped their name on them, which you can easily see if you visit the bridge.

How the columns were delivered to the LIW is hard to say, but I have little doubt the Delaware River was involved. Phoenixville is just a short distance northwest of Valley Forge, PA, sitting on the Schuykill River. Another possibility is trucking the materials overland to the Delaware Canal.

The Lambertville Iron Works made all the cast iron pieces and took on the job of assembling the bridge. To get the columns and other parts to the bridge site, William Johnson had to either load them on heavy wagons pulled by teams of oxen, or load them onto canal boats and haul them up the feeder canal to the point where Federal Twist Road meets the canal, then put them on wagons to take them up the hill to the construction site.

This would have been possible, since canal boatmen had figured out how to allow boats going in opposite directions to pass each other. But boats pulled by mule teams would not have worked because the tow path did run further north than Brookville, which means steam-driven canal boats would have to be used. But this is entirely realistic, according to Linda J. Barth, and would have made the most sense for a company already located right on the canal.22

In the meantime, workmen would have been making repairs to the abutments that had been damaged in the flood of October 4, 1877, and removing what was left of the damaged bridge. This summer the TransSystems Company had the use of heavy trucks, paved roads, and modern technology to take down the bridge, repair it and reinstall it. Such was not the case in 1878. To think that the bridge was finished less than a year after the contract was awarded, without the use of modern equipment, makes the achievement even more impressive.

I rather doubt there was a ceremony when the bridge was completed. New bridges were not unusual during this time period, and people probably did not thinks so much about photo opportunities as they do today. I’d like to imagine Mrs. Cowin breaking a bottle of champagne over one of the Phoenix columns to declare the bridge officially opened, but I am pretty certain that never happened. It should have.

Afterword

The Lambertville Iron Works, Carolyn Cowin and William Johnson

By 1880, Mrs. Cowin had handed over the business to her younger brother, Ashbel Welch Jr. (1854-1944). In describing the company, Snell wrote that The Lambertville Iron-Works “are now in the possession of Ashbel Welch Jr. The principal business consists in making of patent axles, of the patent Eclipse safety-boilers, and of steam-engines. The making of axles, which is a new branch of business in this establishment, is steadily increasing.”23

It is noteworthy that the description makes no mention of iron truss bridges. This may be because shortly after the 1880 census, William Johnson had departed. In 1880 he was 49 years old, a resident of Lambertville, employed as Superintendent of the Iron Works. With him was his wife Sarah (age 46) and four of their seven children (Kate, Gertrude, Herbert and Walter). By 1900, William Johnson had given up the hard work of running an iron foundry and become a professional—he was a patent lawyer. No doubt his experience acquiring patents served him in good stead. In 1900 he was 69 years old and widowed, living in Chicago (Ward 32) with his daughter Gertrude Curtis, also widowed, and her children.24

When the 1880 census was taken, Mrs. Caroline Cowin had moved out of her grand mansion on 119 North Union Street and was living at 135 North Union. Her children, Lucy 15 and Walter 12, were both at school. In a separate household at the same address were James D. Hann 28 and Mary C. Hann 24, servants. Across the street at No. 134 was her brother Ashbel Welch Jr. age 26 (no occupation given), his wife Emma D. Finney, age 24, and their baby Russell 11 months (born July), with Bridget Thompson 27 and Kate Hunt 18, servants.25

Twenty years later, Caroline Cowin had moved away from Lambertville. She was living in Trenton with her daughter Lucy, age 25, and son-in-law Nelson Oliphant, age 43, a physician. Mrs. Cowin was a 56-year-old widow. Her son Walter had moved to Philadelphia where he was employed as an electrician. In 1905, Carolyn Cowin sold her husband’s Union Street mansion to George W. Prall for $8500.26 She died on February 25, 1918 in Trenton, and was buried next to her husband in the Mount Hope Cemetery.

Ashbel Welch Jr. and the LIW

By 1883, Ashbel Welch was actively promoting the Iron Works. He published an “Illustrated Catalogue of the Lambertville Iron Works” that year.27 He also managed to find a new partner. This notice appeared in “The American Engineer:”

Lambertville Iron Works, Lambertville, N.J.—We have received the following circular:

Lambertville, N.J., Dec. 1, 1883. Gentlemen:–We beg to announce that we have purchased the interest of Mr. Ashbel Welch in the Lambertville Iron Works and expect to continue the business as heretofore conducted, including the manufacture of the Lambertville Iron Works Patent Automatic Cut-off Engine and other engines and machinery. With our increased facilities we will be able to fill any orders entrusted to our care with promptness and satisfaction and it will be our aim to maintain the high standard of excellence which has always characterized the work of this establishment. Thanking you in the name of Mr. Welch for past favors, we solicit a share of you business for the future, / Yours respectfully, LAMBERTVILLE IRON WORKS / John Finney President, Ashbel Welch, Treasurer.

John Finney was an extremely successful lumberman, who had probably cut all the lumber there was to be cut in south Hunterdon by this time, and may have been looking for another outlet for his energies. It should also be noted that John Finney was the father-in-law of Ashbel Welch Jr. His daughter was Emma Delia Finney (1855-1926), who married Ashbel Welch on Jan. 1, 1878. However, this new partnership did not succeed in finding its niche. As of August 2, 1886, the charter for the Lambertville Iron Works was no longer in force.28

By 1900, Ashbel Welch Jr. had, like William Johnson, moved away from Lambertville. He was living in Gynedd, Pennsylvania that year, and in 1920, he and wife Emma had moved to Philadelphia. She died there in 1926. During his later years, Ashbel Welch traveled to Barbados at least twice, and died there in 1944. Both of them are buried in the Mount Hope Cemetery in Lambertville.

———————————

Thanks to Barbara Plunkett for sharing with me the application she made to put this bridge on the National Register. Also thanks to Charles Taylor for attempting to educate me on the subject of cast and wrought iron, and to Linda Barth for background on the workings of the D&R Canal.

Footnotes:

- Through her mother, Caroline Welch Cowin was the great granddaughter of Sen. John Lambert (1746-1823). See Snell’s History of Hunterdon County, p. 290. ↩

- Hunterdon Republican, Dec. 3, 1874, as abstracted by William Hartman. ↩

- There was another patent for this company that got some attention in Scientific American magazine; it was called “The Lambertville Iron Works Automatic Cut-Off Engine” (article is behind a paywall). ↩

- In the Beacon Light by Sharon Bisaha (2012) states that the Lambertville Iron Works was founded in 1873. We know that is not the case, as it was functioning as early as 1866 under William Cowin. ↩

- I have not examined the freeholders’ minutes to see who got that contract, and the location of this “Rio Grande” remains a mystery; it must be either the Wickecheoke or Lockatong Creeks, unless the name was tongue-in-cheek for a much smaller creek. ↩

- Hunterdon Republican, July 31, 1875. ↩

- Hunterdon Republican, Aug. 23, 1877. ↩

- Hunterdon Republican, Oct. 4, 1877. ↩

- I looked online to see if a hurricane had come through at this time, or least a tropical storm, but the only storms of record came through about a week before and a week after October 4th. ↩

- from Bucks Co. Gazette. ↩

- Landsdowne Bridge, Lower Landsdown Road over Capoolong Creek, metal 5-panel pin-connected Pratt through truss, 94.2 feet, built 1885 by Phoenix Bridge Co. of Phoenixville PA. It is similar in appearance to the Raven Rock Rd. bridge, but not as pretty. ↩

- Hunterdon Republican, 25 Sep 1873, as abstracted by William Hartman. ↩

- Note that the “bridge card” for bridge D300 in the County Road Department states that the bridge was built in 1876. This is not correct. ↩

- Taken from the Plunkett application to the National Register. ↩

- Matthew J. Kriegl wrote a dissertation on “The Preservation of Single-Lane, Metal Truss Bridges in Hunterdon County” in 2011. He included this bridge in his “Category 1,” bridges eligible to be listed on the National Register. The dissertation can be found online and at the NJ State Library. ↩

- Apologies to engineers out there for my very simple descriptions; I’m writing for people like me who are mostly clueless about these things. ↩

- I had hoped to find a copy of the Reeves patent online, but did not succeed. ↩

- See New Jersey Department of Transportation, The New Jersey Historic Bridge Survey, prepared by A.G. Lichtenstein & Associates, Inc., 1994. ↩

- Charles S. Taylor, Letter to John Glynn, County Road Dept., June 1, 2012. ↩

- Historical Society of the Phoenixville Area, “Phoenix Iron and Phoenix Steel Co.” ↩

- Hiram Deats, Marriage Records, Hunterdon County, 1795-1875, p. 81; Hunterdon Co. Marriage Records, Hunterdon Co. Clerk’s Office, Bk 1 p. 63. ↩

- Thanks to Linda for sharing her extensive knowledge of the history of the D&R Canal. I encourage readers to visit her website, buy her books and attend her lectures. ↩

- Snell, 1881, p. 283; He also stated that the Iron Works were “first established here by Laver & Cowin in the spring of 1849.” This date is incorrect, since the partnership was not announced in the paper until 1857. Many future writers would repeat Snell’s mistake about the year 1849. ↩

- It is frustrating that I was not able to find any more information about Johnson online, not even a death notice. It does not help that his name is so common. ↩

- The Census of 1880 included street names and addresses for towns like Lambertville. But a search for 119 North Union Street, the home of William Cowin in 1870, turned up empty. Perhaps there was no one living there in 1880. ↩

- Deed 276-697. ↩

- I found a reference to this online but have not seen a copy. ↩

- from Corporations of New Jersey, p. 818. ↩

Andrew Pearce

April 16, 2015 @ 3:43 pm

Thank you for part two of this great essay. You’ve done a ton of research and seem as enthusiastic about Hunterdon County history as I am. Regretfully, you continue to state that the Raven Rock Road bridge is the oldest Phoenix Column bridge in the county. Perhaps Tom Mathews, whom I’ve known for years, told you this. Regardless, there are at least two that are older. The School Street bridge in Glen Gardner dates to 1870, and the Shoddy Mill Road bridge in New Hampton dates to 1868. Both built by Cowin’s company, both designed by Francis Lowthorp.

The use of both cast iron and wrought iron was the thesis of Francis Lowthorp, who also designed the 1870 iron bridge in Clinton, also built by Wm. Cowin company. Cast iron had been used worldwide in many bridges up to that point, but several major disasters frightened people away from cast iron. Lowthorp figured out that wrought iron was stronger in tension (stretching) while cast iron was stronger in compression, and built his bridge that way. Steel is far stronger than either for both, but steel rusts through, whereas iron rusts on the surface and then stops. Thanks to the Bessemer Process, steel became inexpensive by the 1880s, and the rest is history.

Once the 1857 Fink Truss bridge on Hamden Rd south of Clinton over the South Branch was accidentally destroyed in 1978, these 3 became the oldest bridges in the county.

Speaking of history, the story of the Phoenix Column is a great one, figuratively beating swords into plowshares. The Phoenix Iron Company built the strongest cannons used in the Civil War. They were made from laminated wrought iron, hot sheets rolled around a mandrel in layers like a scroll. Faster to build than casting iron, they also had a singular advantage of NEVER blowing up. That same skill, perhaps even the same machines, later bent sheets of wrought iron into lipped quarter round lengths, riveted together on site to become columns. These things are older than I beams, and were used to make buildings as well as bridges.

As much as I admire the Raven Rock Rd bridge, my personal favorites in the county are the 1900 Rockafella Mills Rd one in Flemington, and the 1885 Lower Landsdown Rd Phoenix column one just south of Clinton.

Marfy Goodspeed

April 16, 2015 @ 5:09 pm

Andrew, thank you for this very well-informed comment, and for setting the record straight. The other two bridges you mention are indeed lovely and admirable bridges. I’ll put them on my list of subjects to write about.

Art S.

December 25, 2019 @ 10:28 pm

Andrew and Marfy,

The Rosemont – Raven Rock Bridge (D300) is the oldest standing Phoenix Column bridge extant in Hunterdon County. The other Corwin bridges Andrew mentioned (of which there are actually three, not two) have cast iron compression members rather than Phoenix Columns.

Phoenix Columns were an early solution to enable wrought iron to be to replace cast iron for compression (the thick pieces) in addition to tension members (the thin, string-like pieces). The eventual evolution of wrought compression members is the rolled I-beam.

Although the connection blocks for the Phoenix Columns, the bridges shoes and portal decorations are cast iron, at the time, it would have been considered fully wrought iron due to the Phoenix Columns rather than the cast iron columns of the Corwin bridges.

Sincerely,

Art S.

Pamela Jean Milam AKA Brenna

February 23, 2016 @ 11:52 pm

ANDREW,

Is there no picture of the Brookville drawbridge in Trenton, New Jersey around 1889. I found one that claims to be that bridge, however I can’t figure out what in the photo is the bridge. It just looks like a lot of people standing around and is also 1936. Nellie and Katie Lockerbie were living in Stockton, NJ at the time. Their father, a mason, was Robert Lockerbie, straight from Scotland. Their mother was Catherine Ruthven Lockerbie. Robert’s sister was my great grandmother, Jane B. Lockerby(ie) Wilson. She lived in Manhattan. There is an article, which I have most of, though I can’t find it on line. I did find their obituary. Nellie almost 9 was carrying

2 year old Katie across that bridge, and their 8 year old brother was witness to the event. They fell into the Delaware River and David ran for help. They were pulled out, but of course were drowned. This was April 6th 1890. To make matters worse, Jane and John S. Wilson must cave come for the funeral and to help out, and while there, on July 7th 1890, the baby carriage somehow rolled into the river in Stockton and they were both lost. They were less than 8 months old. I have a letter from Robert to Jane detailing the head and foot stones he was carving for the girls. All my mother’s life she heard stories of the deaths, so she took a trip to Stockton to attempt to find them. She located the footstones in the Holcomb River Cemetery, but never found the headstones. My computer and I found them in the Sandy Ridge Cemetery. I guess Robert never got them moved. He died on September 17th 1892 of TB. I have photos of both footstones, small and large. Foot stone photos taken by my mother, and the others on “Find a Grave” By November 7th, she and her remaining children were arriving in Liverpool November of 1992. She had borne 10 children in 11 years. She went home with the remaining children. They numbered 5. She spent her remaining days cleaning a pub in Scotland. How hopeful she must have been upon coming to America. She must have thought shed escaped from hell when she returned home. So you can see why I want what ever I can find including the bridge. I hope I haven’t bored you. I haven’t even a photo of any of the children.

Art S.

June 3, 2019 @ 7:23 pm

Here is an image of the bridge at Penwell: http://bridgehunter.com/nj/hunterdon/bh71802/ hat you reference in your article. it is a bowsting truss. A form that went extinct in New Jersey in the 1990s although some still exist in surrounding states.

I would be very interested to read whatever you would be able to research on the Fink truss as it was one of the earliest and was the last through truss of its type in existence. After the accident the parts were recovered, documented and stored but it is believed that they have since been scrapped.