The following is one in a series of articles that Mr. Bush wrote in which grand old trees were the primary theme. Those magnificent trees are no longer around to inspire us the way they did Mr. Bush. Seeing the world through his eyes reminds us of what has been lost.

The following is one in a series of articles that Mr. Bush wrote in which grand old trees were the primary theme. Those magnificent trees are no longer around to inspire us the way they did Mr. Bush. Seeing the world through his eyes reminds us of what has been lost.

“California” A Paradise for Birds’, Boys, Berry Pickers

Magnificent Oaks Were Sacrificed for Ship Timbers.

One Old Resident Remains

by Egbert T. Bush, Stockton, N. J.

published by the Hunterdon Co. Democrat, March 13, 1930To most people the name California suggests immense trees and great orange orchards; to a few of us it more forcibly brings up mental pictures of big stumps and thrifty patches of blackberry briers. As seen in memory’s mirror, these are scattered over a big inclosure of at least 150 acres of ground that had lately been covered with magnificent oaks and other varieties of timber that grew so luxuriantly in the “Great Swamp.”

We find that the “California farm,” of which this inclosure was a part, as conveyed by Albertus K. Wood, Susan B. Button, Sarah C. Roll and George W. Roll to George A. Rea and Runkle Rea, of Flemington, by deed date May 17, 1881, contained 250 acres: “Beginning at a corner in the public road leading from the Klinesville Schoolhouse to Baptisttown, &c. Being the same that was devised to Phoebe Wood, her heirs and assigns, by Jeremiah King by his last will and testament dated August 27, 1821; and the parties of the first part being the only children and heirs at law of the said Phoebe Wood who has departed this life intestate.”

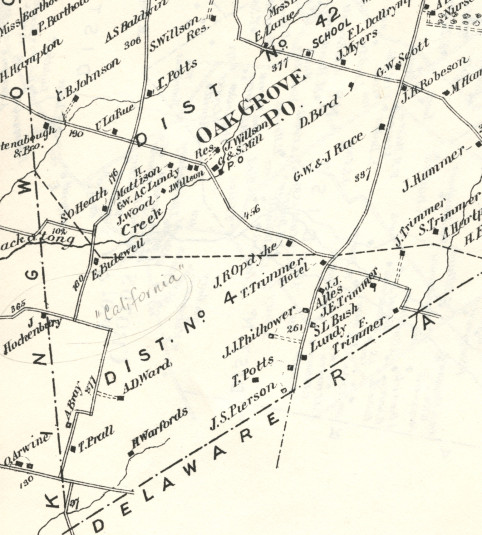

The Great Swamp, as Mr. Bush knew it, is now identified as the Croton Plateau, running from Quakertown south to the hills overlooking Route 523. The farm sold by Wood, Button, and Roll to George and Runkle Rea was located near the Locktatong Creek just south of the Oak Grove Post Office, as shown on the Beers Atlas map for Franklin Township. The deed mentioned by Mr. Bush was recorded in Book 193 on page 86. Bordering owners of the Wood farm were Asher D. Ward, Jacob J. Philhower and Josiah Wilson. Also G. W. A. C. Lundy, C. B. .Johnson and E. Bidewell. These names appear on the Beers map.

Mr. Bush made a reference to the Wood tract in another article, titled “Franklin: Charred Ruins Recall Memories of a Bygone Day,” published April 7, 1932: “By deed dated March 26, 1867, William L. King conveyed the original farm of 155.70 acres, “Beginning at a corner to lands of G. W. A. C. Lundy in John Wood’s line” (the old California line) . . .”

Mr. Bush made a reference to the Wood tract in another article, titled “Franklin: Charred Ruins Recall Memories of a Bygone Day,” published April 7, 1932: “By deed dated March 26, 1867, William L. King conveyed the original farm of 155.70 acres, “Beginning at a corner to lands of G. W. A. C. Lundy in John Wood’s line” (the old California line) . . .”

What I do not see on the Beers map is a school nearby. The school district number shown on the Beers map seems to have been truncated; I assume it is supposed to be 41 or 43, but I cannot find a schoolhouse in that district. There is a school further north between E. Larue and J. Myers, though, part of District 42.

In his history of Hunterdon County, James P. Snell did not mention a Klinesville School in Kingwood Township. Here is his description of District 42 in Franklin township: “Franklin,” No. 42, was formed chiefly from the lower part of the Quakertown District, though it is probable that district-lines received but little attention at that day. The fist house, a small log structure, was built in 1826. The first teacher was Amos Lundy. . . . From the circumstance of its [present] location this school is sometimes called “Maple Grove.” A new schoolhouse was built in 1871, at which Mr. Bush was one of the teachers, which leads me to conclude this is not the schoolhouse known as Klinesville.1

What is surprising is that Mr. Bush does not give us a clear reason why the name California came to be used for this bit of swampy ground. Anyone who had actually been to California would not think of choosing such a name for this place. But then Califon, also said to be named for California, is not very likely either. It was not the place itself so much as the aspirations of its residents. Califon’s name came “from Jacob Neighbor’s enthusiasm in the milling business about the time the California gold-fever broke out.”2 Perhaps the Woods or their neighbors had a similar motive. Mr. Bush continues:

We further find that by deed dated May 1, 1792, Elizabeth Cadwallader conveyed 480 acres, of which “California” is a part, “Lying in the Great Swamp, Beginning where a beach tree formerly stood near a Brook called Laokalong, Marked A. S. and being one of the corners of the 5,000 acre survey made by Amos Steckle.”

That “Amos Steckle” was actually Amos Strettle, who had a tract of 5000 acres surveyed in 1711, just north of Croton on the west side of Rte 579.

It then ran along lands of James Willson, at that time the owner of the Oak Grove farm and mill property of later days. At the time of gathering memories of the big inclosure, it touched the farms of Jacob J. Philhower and Daniel Sebold and, for a short distance, the public road above mentioned. But why that many-angled, roundabout road was ever called the road leading from the Klinesville School House to Baptisttown, is hard to understand.

It is also hard for me to understand, as the Beers Atlas does not show a school in the vicinity of the Woods’ farm. But then, I’m rather fuzzy about the location of Klinesville, and welcome any readers’ suggestions.

Mr. Bush proceeds to describe what it was like to view a large area that had been timbered in the late 19th or early 20th century. It must have been quite a sight.

California Trees

The writer never saw the California trees in all their glory, or even as their glory was departing. When he first saw the tract there was but one tree left on all that large area of stumps and briers. That was a vigorous young gum, growing in solitary grandeur several hundreds yards from any other tree. And how popular it was as a resting station for various kinds of birds! The redheaded woodpeckers then so plentiful and now so scarce, were particularly fond of that restful station. So plentiful were these birds that not to have seen several in any day of the bird season would have been remarkable; if we see one in a whole summer now, we tell proudly of our good fortune. It seems, that even the Woodpecker has his little day, and must then pass from the stage to be seen no more. But is not this the law of life?

It is evident, then, that the writer must depend, for the glory of primitive “California,” upon three things; namely, the stories that were told by those who knew, the stumps which still bore evidence of great girths, and his own imagination—lively enough, no doubt, but restricted by knowledge of the trees then remaining on near-by tracts of fine timber. The stories may have grown somewhat, as stories have a curious habit of doing, but the stumps had not; and imagination of such things cannot go far beyond the realities by which it is surrounded.

Huge Stumps

Some of the stumps were already well rotted; others appeared to be perfectly sound. Here and there were the remains of some monster trunk that must have fallen long before violent hands were laid upon its neighbors. And how the briers did flourish around those rotting stumps and rotten logs! “Stump dirt” was the accepted name for such decayed wood, after it had reached the right condition to be used as a fertilizer for flowers and other choice plants. This and what remained in the soil from the decaying leaves of ages, always left “new ground” rich in materials necessary to the growth of certain crops. Nowhere else would buckwheat grow so vigorously, throwing out those tremendous branches which the plant is so capable of loading with beautiful bloom and profitable harvest.

Old-timers often rehearsed a story that may be of interest here. A farmer, who{se} name is now forgotten, tho familiar then, had three or four acres of new ground “scratched over” and ready for sowing. For some reason he was suddenly called away from his work. So he said to his son—a mere lad—”You’ll have to sow that buckwheat.” And away he went without giving the necessary instructions, as was still the perplexing habit in days somewhat later. It was the boy’s business to know, as some of you may understand.

When the father came home, the boy informed him. that all was done as ordered, and -proudly added: “Lucky, ain’t it? It’s goin’ to rain, sure.”

“How much seed did you sow?” “Almost a bushel.” “What! Almost a bushel when it should have been four! The birds will take a lot of that little, and we’ll have no buckwheat. Too bad!”

It did rain, and they were unable to remedy the mistake. But the crop was not quite ruined. The one bushel yielded 101 at the harvest—a story that lasted for generations as showing the greatest yield ever known from that amount of seed; and all within the bounds of probability.

The Woods Owned California

California was then lying in the name of John Wood, who had married Phoebe, daughter of Jeremiah King. The name Wood became quite familiar, tho the family lived at Linden, N. J., and were rarely seen here. The Woods sold off the timber but kept the land, and developed the business of herding on the big inclosure from 50 to 75 head of cattle during the summer. How the cattle were disposed of, we never knew. They came each spring and were taken out each fall. That was enough for us to know. I remember how we watched for the arrival of “Wood’s cattle,” to be driven thru the long Philhower lanes to their destination, this going across saving some two miles of travel for weary men and perhaps still more weary cattle. In later years the name became “Roll’s cattle,” George W. Roll having married Wood’s daughter, Mary C., and apparently taken over the cattle business.

Jeremiah King (1736-1822) and wife Sarah Rittenhouse (1761-1849) had 11 children, including Phoebe King (born March 9, 1794), who married John Wood on January 29, 1814. In 1821, Phoebe’s father Jeremiah wrote his will leaving to daughter Phebe Wood, wife of John Wood, a tract of 250 acres, part of the Lambert tract purchased from Elizabeth Cadwallader.

Jeremiah King’s first wife is said to have been Phoebe Craig, whom King married in 1759. But she died childless in 1778. King must have married Sarah Rittenhouse almost immediately, because their first child, John, was born on July 17, 1779.

California was an ideal place for that purpose. It seemed to have “all the modern conveniences.” Plenty of water for drink and for luxurious bovine baths was furnished by the Lackatong creek, which ran thru the northwest corner of the inclosure. The stream was shaded by trees that had been left growing on both banks, probably for this special purpose. Cattle could feast on grass and then loll in the shade or wade into the water and splash to their hearts’ content. What more could bovine taste, or bovine whim demand?

Some of us in early childhood became well acquainted with that big inclosure of stumps and briers, and with the cattle that roamed over it. How people dared risk small children in such wilds and among cattle of unknown dispositions, has been a wonder for later days. But perhaps we should remember two things; that children did not amount to so much then, and that the little which they could earn by gathering nuts or berries probably justified a risk so slight in hope of greater gain. Anyhow, no child was ever injured there, so far as is now known, and none was ever hopelessly lost. If one did, on a certain occasion, become confused, climb over the wrong fence and go west instead of east, what of it? Children must learn to shift for themselves, you know, at least, according to the older code. But to be lost does cost a fearful waste of heartbeats and something else that cannot be described. Let us forget all about it.

A Dollar Looked Big

Conditions just suiting them blackberries grew in California as nowhere else in that vicinity. Berries were needed for home use. They grew here in profusion and were free to all. Why not have us get a share? We got them for a few years, and then something happened—something big. Word came that the Croton merchant was agent to buy berries for the city market. That was news—big Wall Street News. The price was four cents a quart delivered at Croton, the merchant to do the measuring and be the judge of salability. There was nothing unfair about that, unless it was the price. But little was thought about that. Two or three children in a family could earn something worth having. But it was slow money, indeed. If berries were plenty, so were pickers, especially after the market opened. It cost many a weary day for very little money. Perhaps the best thing about it was, that it made a dollar look so big.

The Courtney [sic] Boys

The newspaper employee in charge of making up headlines for the sections of Mr. Bush’s articles was not reading very closely. This heading should read: “The Roberson Boys”.

Of course there was a tenant farmer on the California property; but he never bothered the pickers. “Help yourselves” was the rule; and everybody observed it. Charles Roberson was the tenant there for several years. He had a, family of four boys—John, Thomas, Stacy and Courtney. Thomas and Stacy died single soon after reaching manhood. John bought the still-house farm at Quakertown, but never did any distilling, and died there several years ago. Courtney bought the William Mathews property adjoining the Snyder poor farm southwest of Quakertown, and died there a few years ago.

Charles Roberson, born c.1815, married Dec. 30, 1843 Sarah Stout, and had 4 children (John, Thomas, Stacy and Wm. Augustus). Mr. Bush wrote that they also had a son Courtney. This was in fact William Augustus Courtney Robinson, generally known as Court Robinson, born 26 October 1853, died 1910 in Franklin Twp. His first wife was Ann Elizabeth (Lizzie) Trimmer (1859-1885), daughter of Servis Trimmer and Ann Anderson. They had one daughter, Jennie, born on Aug 14, 1878, who married Albert A. Leaver, and died on Feb. 12, 1945. Court Robinson’s second wife was Susan A. Hartpence (1858-1939), daughter of Enoch Hartpence and Esther Holcombe, and widow of Israel P. Trimmer (1854-1888).

I was unable to link Charles Roberson to the Roberson family of Kingwood. The articles of J. Bellis did not shed any light, nor did the extensive genealogy of the Robeson/Roberson families by Althea F. Courtot and Louise H. Tunison, published in 1986.

Stacy Roberson is remembered as an expert player in good old “corner ball”. Some of you remember how the ball was tossed from corner to corner until all had been served, and must then go diagonally before it could be considered legally “hot.” You remember also how the corner man with a hot ball was likely to “warm” somebody within. Stacy’s forte was in not getting “warmed.” He never wanted to be far from the thrower and never faced him. Tall, straight, and thin, he stood sideways to his antagonist, keeping a sharp eye on him, and presenting the narrowest possible target for the marksman. No matter how skillfully the ball was thrown, the chances were about ten to one that Stacy would not be there when the ball arrived; and yet he never showed much motion; just a slight movement backward or forward, and the ball sped past, leaving Stacy untouched. It was the best exhibition of coordinated sight calculation and action that I have ever seen to this day.

Stacy (or Stacey) Roberson was born about 1851, died in Franklin Township on 8 Nov 1872, age 21. The death record on Ancestry.com did not give a cause of death.Ship Timber from Big Trees

The writer cannot vouch for all that was told of what “we did when we cleared off California.” The stories were largely about getting out “ship knees,” “keels” and various kinds of “ship timbers;” all terms never heard from woodsmen of the later days. Steel soon took the place of oak, and knees for ships were no longer matters of interest or conversation. It appeared that the natural angle formed by a great limb, with the bole of the tree was used to avoid “cross-grain” in the knee; and that great roots were sometimes used in the same way. All talkers and listeners seemed to agree that this was the only way to make reliable “ship knees,” tho it required much labor and great skill to work out a part of the bole and a part of the limb or the root in the same crooked stick; and especially to find and work out numbers of them with the same angle.

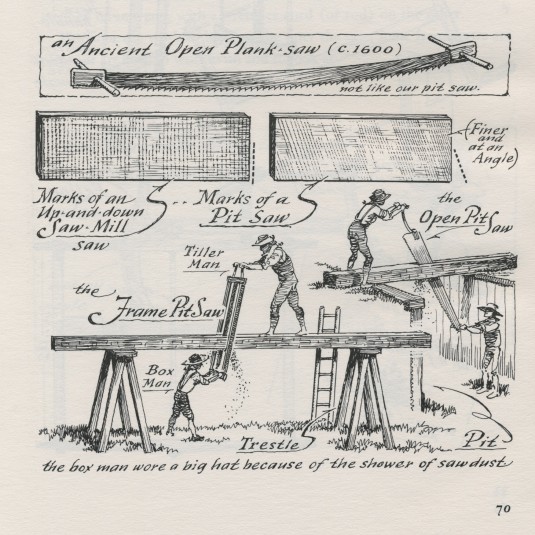

That looked reasonable; but the early manner of sawing pieces from logs too big or too long for the mills of those days, has always been a puzzle. Yet memory is very clear as to the process described. The great log was raised by derricks and securely fastened so far above the ground that a man could stand anywhere under it. When ready, it was the work of special sawyers—an “upper sawyer” and an “under sawyer,” one standing on the log and the other under it—to saw it from end to end as often as required for making a keel or keel-piece for some great ship. So far as known, this costly primitive method—if actually as represented—went out of use before the writer’s day; but it is interesting to wonder over even yet.

Time Has Worked Changes

Time, aided by man’s genius for destruction, has made many changes during the years since California became the neighborhood berry patch. Probably the big inclosure has not kept pace with the changes, but its surroundings have. Then, within a mile of its borders, lay hundreds of acres covered by fine virgin forests; find five acres there now if you can. Then the farms of the vicinity all appeared prosperous; now evidences of agricultural prosperity are the exception. Then farm machinery was scarce, simple and well protected; now there is machinery for everything—plentiful, complicated and neglected. Then old-time families were all about it; now few such families have any representative there. The old people are gone, of course, and the young of those days have mostly followed them. Of all those who then lived within a mile of the big inclosure, only one is to be found there now.

Sharon Moore Colquhoun

May 8, 2015 @ 6:19 pm

Very nice article. I love Eric Sloane’s drawings and I knew Althea Courtot; she was a lovely person and we all called her “Robin.” We both worked at the Roselle Public Library in Union County NJ. That was back in the olden days of the 1970s when genealogy had to be done without computers. We actually discussed and compared family trees alth0ugh my tree was rather slim then!

Virginia Johnson

May 8, 2015 @ 11:19 pm

Klinesville is in Raritan Township. The easiest way to locate it today is to reference Cervenka’s Farm Stand. Generally it is Oak Grove Road to the south, Featherbed to the west, a little north of Allen’s Corner, and Klinesville Road/617 to the east. On the 1873 map it is School District 80. The school appears to the on the west side of Featherbed across from A. Sheppard, probably on the corner with Oak Grove. (I believe this is Andrew who was instrumental in building the Hemlock Church). In his article about the Cherryville school Bush says that there are four schools within “two miles” of the rake factory: Cherryville, Klinesville, Drybrook, and Hardscrabble. Looking at today’s map I think the road Bush thinks should have been called Klinesville School-Baptistown Road is probably Oak Grove which does go through what was Strettle’s 5,000.

Marfy Goodspeed

May 9, 2015 @ 6:07 am

Thank you Virginia! Just looked at Raritan Twp. on the Beers Atlas, and there it is, larger than life.