Published in The Bridge (newsletter for Delaware Twp.) in August 2001

Some time ago, I gave a talk about how Delaware Township’s villages came into existence. It seems appropriate to adapt that talk to the newsletter, in several installments, since villages are still, despite our 21st century way of life, important to our township.

Villages don’t just happen. There’s a reason why each one comes into existence, although sometimes not much of a reason. Villages might start with a location where two trails intersected, or at a good fishing spot. A ferry attracted a tavern, a mill attracted a store, and soon there would be a village. The first villages were created by the Lenape and the more ancient native peoples who preceded them. Lenape villages were of two types, the permanent and the seasonal. The only permanent village in this area was located at northern Lambertville, at the mouth of the Alexauken Creek. Evidence of the Lenape in other areas in Delaware Township (and there is lots of evidence) indicate seasonal fishing and hunting locations, temporary villages, especially at the mouths of the Wickecheoke and the Lockatong Creeks, but also inland at good deer hunting locations.

Some of these Lenape villages were adopted by the later European settlers. There was often a cleared area where the Lenape gardened, and cleared areas were always attractive to Europeans. 18th century villages were modest. But following the Revolution, village life became very active. Stores and shops of all kinds increased significantly and post offices were opened. In 1834, Thomas Gordon identified only Prallsville as a village, with one store, one tavern, some 6 or 8 dwellings, a grist mill, and “a fine bridge erected over the Delaware.” Obviously he had combined Prallsville and Stockton, but at that time Stockton didn’t exist. Gordon did make note of a post office at Sergeantsville.1 By 1844, Barber and Howe identified Sergeantsville, Headquarters and Raven Rock, in addition to Prallsville, as recognizable villages.

Villages were the center of the neighborhood, the place where people gathered to take care of business, share their experiences and just have a good time. They were lively places, especially on Saturday nights. But once the automobile arrived, especially following World War II, America became a different place, a place that no longer had much need for villages. Local post offices were closed, small stores yielded to larger ones further away, and soon there was no longer any reason to congregate in a village. Today Delaware is one of the few townships left in New Jersey that still has recognizable villages.

These are the ingredients for an 18th century village in Delaware Township: a ferry, a tavern, a mill, and a store. A blacksmith shop would also be an attraction as well as a church, a school and an intersection of roads. Such intersections were important for the simple reason that there were so few of them. The roads that did exist were not much more than dirt paths. Because traveling was so difficult, people did it only when necessary. Milling was an unavoidable necessity. Whereas farmers managed to be self-sufficient in most things, the ability to grind one’s grain or full cloth or press oil were not skills that every farmer could manage. The earliest settlers of West New Jersey had to grind their grain with hand mills or pound their corn with a mortar and pestle in the Lenape style. So it is not surprising that mills were built very soon after people began to settle in this area. About 1680, Mahlon Stacy built the first mill in West New Jersey at Trenton.

Not counting Daniel Howell’s mill at Prallsville, which was probably built about 1710, the first known mill in Delaware Township was constructed at Headquarters by John Opdycke or his brother-in-law Benjamin Severns in 1735. It was rebuilt in 1754 by John Opdycke and in 1876 by John Carrell. It remains a beautifully built and sound structure, whereas nearly all the other mills are gone, excepting the mill at Prallsville, the sawmill on Strimple’s Mill Road and the Rittenhouse/Myers Mill on Old Mill Road, the latter being converted to a residence. The mill on Strimples Mill Road is the only one left that is still operating as a mill.

This is a big change from 1840 when Barber & Howe found six gristmills, six sawmills, and one oil mill in Delaware Township. Jonathan Hoppock wrote that the Wickecheoke Creek alone powered four grist mills, six sawmills, one oil mill and one fulling mill.

In 1851, a map of Hunterdon County was published which showed property owners and businesses. There were five sawmills listed, at Croton, the Myers mill on Old Mill Road, the Sergeants mill at the covered bridge, the sawmill on Strimples Mill Road and a sawmill and clover mill at the Rittenhouse farm on Reading Road. Grist Mills were the Myers Mill on Old Mill Road, the Sergeants Mill, Conover’s mill at Headquarters, Hiram Moore’s Mill at Sand Brook, J. P. Hunt’s mill on the west side of Buchanan Road, Hiram Deats’ mill at Brookville and the mill at Prallsville. In 1873, the Beers Atlas served the same purpose as the 1851 map, but with more detail. Mills were shown at Croton and Prallsville, a sawmill at Brookville, a saw & grist mill on Old Mill Road, Sergeant’s saw & grist mill, Carrell’s grist mill at Headquarters, and sawmills on Strimples Mill Road and Reading Road.

The Cornell Map of 1851 and the Beers Atlas of 1873 both indicated locations of mills in the township as follows:

Brookville: 1851 “H. Deats Mill,” 1873 “S. Mill.”

Buchanan Road: 1851 “J. P. Hunt’s Gr Mill,” 1873 nothing.

Covered Bridge: 1851 “G. Mill, S. Mill” (separate locations), 1873 “G. Sergeants’ Mill.”

Croton: 1851 “S. Mill,” 1873 “S. Mill.”

Headquarters: 1851 “G. Mill,” 1873 “ Conovers G. Mill.”

Old Mill Road: 1851 “G & S Mill,” 1873 “S & G Mill”

Prallsville: 1851 “G. Mill,” 1873 “Kessler & Co. Quarries, mill, store, office.”

Reading Road: 1851 “Wm [sic] Rittenhouse S & Clover Mill,” 1873 “S. Mill.”

Sand Brook: 1851 “H. Moore’s Gr. Mill,” 1873 nothing.

Strimples Mill Road: 1851 “D. Carles Mill”, 1873 nothing.

Clearly, Delaware was well equipped with mills. Some of the mills listed above were associated with villages, but others were not, specifically, the Strimples Mill, the Myers Mill, the Rittenhouse Mill and Hunt’s Mill. There were at least another two mills not listed in the 19th century maps. One was the Thatcher Sawmill which Jacob Thatcher operated on his farm north of Sand Brook. The Cornell Map shows a “J. Thatcher” owning property along the east side of Route 579 where the Mason Farm was later. The other mill belonged to Elnathan Werts, brother of George Werts. He ran a sawmill from the waters of the Wickecheoke Creek that ran through his farm near Whiskey Lane. Another interesting mill was the Lawshe Cider Mill on the original homestead of the Covenhoven family in Headquarters. But that gets into the subject of distilleries, of which there were also many. A discussion of distilleries will take place in a future article, along with the many saw and grist mills that have been listed here. Future articles will also describe the other institutions found in villages—stores, taverns, schools, churches, etc. If you have any questions or information to share, please add a comment.

Postscript, 1/14/2022: That prediction of articles to be published was a little optimistic. Since 2010 I have not published nearly as much as I expected to, simply because there is so much to write about.

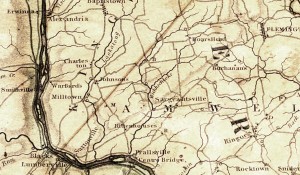

- The detail of Thomas Gordon’s Map of 1834 was part of the original post. ↩