Observers of Hunterdon history on Facebook have called our attention to the anniversary of the fire that destroyed the Hunterdon County Courthouse on February 13, 1828. This inspired me to look at the Hunterdon Gazette for 1828 to see how people reacted to this disaster.

The Gazette was published on Wednesdays, but the fire happened on a Wednesday, so obviously the edition for February 13th said nothing about the event. But the next edition, on February 20th, was full of the news. This was the editorial:

FIRE. – On Wednesday night [February 13th] the people of this town and neighborhood were roused from their midnight slumbers by the alarm of fire. It was soon ascertained that our county Court House was on fire, and by the time we had assembled on the ground, the flames were issuing from the roof near the southwest corner of the building. The want of an effective Fire Engine and its accompanying apparatus necessary on such an occasion, soon convinced us that all attempts to rescue the Court House from the devouring element would be futile; all attention was therefore directed to the preservation of the adjacent buildings, and not without fearful apprehensions for the issue. Favored as we were by almost a dead calm, and having abundance of water at command, exertions were directed with such effects as to keep the stores and public offices, and other buildings most exposed to danger, constantly wet and completely saved them. In the meantime the fire raged within the walls of the house with great fury – the cupola and bell were soon dislodged from their fastenings, and precipitated to the interior of the building – the roof soon followed, and before daylight of Thursday morning, there was little to be seen of our venerable old court House but the naked walls, and the smoking embers of its ponderous timbers.

Keep in mind that the building that was destroyed that night was built in 1790-91, when the capital of Hunterdon County was moved north from Trenton to Flemington. Apparently the reason for that was Flemington’s more central location, since the county at that time extended from Trenton all the way north to the Musconetcong River.

The original courthouse was 60 by 35 feet, two stories, the first 9 feet high, the second 14 feet, and resembled Joseph Reading’s house, built in Delaware Township in 1787, although I am not certain that it was built with stone the way the Reading house was.1

The story could have been of a much greater disaster, as the Gazette’s editor, Charles George,2 relates:

To the calmness of the night we are indebted, under Divine Providence, for the preservation of our town. Had the wind been high, and the flames been communicated to the dwellings and contiguous stabling on either side the street, there is reason to believe most of the central buildings of our town would have been laid in ruins. The public records, we are happy to state, are all safe. The clerk of the court, perceiving the imminent danger to which they were exposed, caused the books and papers belonging to his office to be removed to a place of greater safety; and it will cost him some time and much labor to replace them in their wonted order.

Here the editor gives us a glimpse into the workings of the clerk’s office, in which people would leave their deeds to be copied by the clerk, but take their time to come retrieve them. Keep in mind, it was the purchasers of properties who needed the deeds to prove they had title to their properties.

This labor [of putting deeds back in order] is needlessly augmented, by the circumstance of a great number of deeds, &c. remaining in the office, which ought long ago to have been called for by their proprietors. Had these papers, with the records of them, fallen a product to the flames, their owners might have burned their fingers in searching for their titles to property among the smoldering ruins. – Those interested would do well to take the hint.

How was the fire started? According to Mr. George, “There is some reason to believe the fire was the work of design.” But nothing was said about who the perpetrator might have been. As a friend of mine observed, “that’s one very cold case.” Perhaps it had to do with the fact that the jail was attached to the courthouse. It was also destroyed, leaving the “keeper of the jail” Steven Albro, homeless in the middle of winter. No prisoners were injured, and the Somerset County jail was able to take them in.

As for a functioning courthouse, the trustees of the Methodist Episcopal Congregation of Flemington stepped in to save the day, offering their meeting house for the use of the county courts, until a new courthouse could be built. It is worth noting here that the Methodists were only returning a favor done to them. The first Methodist meeting held in Flemington took place in 1822 in the county courthouse, and the first meeting house was not constructed until 1826.3

Consequences

The destruction of the Flemington Courthouse brought a simmering controversy to the boil. It concerned the location of the county seat. For a long time, apparently, citizens of Lambertville and others had been agitating for the removal of the county seat to Lambertville.

This is very interesting when one thinks about the history of Lambertville, how construction of the D&R Canal in 1834 had triggered a spurt of development, and then the Belvidere-Delaware Railroad in 1851 gave it an even bigger spurt. But what made Lambertville feel its importance in 1828? It was a growing community, ever since 1814, when two important events took place: 1) the bridge across the Delaware opened for traffic and 2) the town got a post office. Also, Capt. John Lambert had opened his inn to accommodate traffic coming across the river and down from New Brunswick along the York Road. Still, Lambertville was relatively undeveloped at that time.

The editor of the Gazette took a dim view of this business:

We learned that our neighbors of Lambertsville are putting forth all their energies for the procurement of a law to take a vote of the county on the subject of a removal of the Courthouse. – The opponents of such speak without calculation when we state, as our opinion, that a large majority of the people in the county are opposed to any removal. The main objection we have to the decision by a general vote is, that it would occasion unnecessary delay in rebuilding the Courthouse. We need scarcely add, that our columns are open to a liberal discussion of the subject.

Residents of Lambertville had been submitting petitions to the legislature for a county vote on the issue, and now new petitions were submitted. There were letters to the editor of the Gazette on both sides, with all sorts of nasty motives impugned. The pros and cons of the two locations, Flemington and Lambertville, were hotly debated. In late February, “Citizens of Flemington” submitted a “Memorial and Remonstrance” to the State Legislature with this introduction:

That for several years past the inhabitants of the village of Lambertsville [as the town was then called], in this county, have been circulating petitions for the removal of the seat of Justice of the county to that place; during which time they have labored assiduously to satisfy themselves of the propriety of the measure, and convince the public that they would in some way or other be benefited by that change. By dint of unwearied patience and perseverance they have, as is usual in such cases, succeeded in obtaining their own approbation, and the signatures of a large number of persons, some feeling a deep interest in the prosperity of that particular place, and others feeling little or no interest at all in that or any other location; but who could not resist continued and importunate solicitation to subscribe their names to a petition. From the time and pains that have been bestowed on the object, it would not have been surprising if they had obtained the names of half the people, young and old, in the county, which contains about 30,000 inhabitants. But your memorialists apprehend their signatures still fall vastly short of that number.

Some three or four years ago, having obtained a sufficient number of subscribers to give countenance to the measure, they ventured to present petitions, and bearing on the subject before your honorable body, and a bill was actually reported, which upon farther reflection however was abandoned by them, as hopeless and chimerical; and so the project is still considered by the great body of substantial yeomanry of the county, and by many of the most respectable citizens of their own neighborhood. The Legislature have not since been troubled with it until lately, when some fortuitous circumstances, entirely unconnected with their claims on the one hand, or the public interest on the other; but backed by the recent destruction of part of the public buildings at this place, have again encouraged them to press the subject on the attention of your honorable body.

Flemington in 1828

The Remonstrance then presented the Flemington side of the argument, including these interesting tidbits:

In pursuance of an act passed in May 1790, the seat of Justice of the county of Hunterdon was, by a large majority (upwards of three-fifth) of all the votes of the county, at an election held in October in that year, located at Flemington. The place at that time contained about 10 or 12 houses; since which time all the property in the village has changed hands at advanced prices, and about 35 new dwelling-houses have been erected, on the faith of the seat of Justice having been established at this place – which now contains, besides 3 churches, and the county offices, (yet uninjured) between 40 and 50 dwelling houses, all occupied, several of them with two families each; besides store houses, shops, and out buildings. There are in the place 4 Taverns, 4 Stores, a Post Office, Printing Office, an Earthen Manufactory, 20 Mechanics of different occupations, 11 Professional Men, and the county officers, besides other citizens – to all of whom a removal would be a sacrifice. And we hesitate not to declare, that Flemington, within the circuit of the village, contains more buildings, public and private, than Lambertsville, and considerably more inhabitants. Some buildings in the latter place, erected some years ago on speculation, remaining to this day unoccupied.

The public buildings in Flemington were erected in 1791, plain, substantial, and sufficiently large for the accommodation of the county; although the court room was not arranged to the best advantage for the convenience of the Court and Bar; and on this account only was an application made by the members of the Bar to the board of Freeholders, for some alterations. . . .

It is true, that some eight or ten years ago, the citizens of Flemington had the water brought to the village in pipes, from a fountain on the adjoining hill; the pipes have been neglected, and finally fallen into disuse, from the circumstance that the town was otherwise well supplied with pure and wholesome water, not to be exceeded in any part of the county. There are within from 100 to 200 yards on each side of the street leading through the village, a number of springs of pure water, three of which have never been known to fail. There are also a number of wells of excellent water in the village, some of which have never failed; besides a never-failing stream of spring water that flows at the foot of the village, not a quarter of a mile from the Court House. Owing to these circumstances or some other cause, for which your memorialists feel thankful, Flemington has always been distinguished as one of the most healthy situations in the county. The town is built on elevated ground, not barren or sterile, but bountifully fertile and productive; and which, like other soils of the same description, is liable no doubt to get muddy in rainy seasons, and dusty in extreme drought – an objection to the site of a county town, which we confess has the advantage of novelty at least, as we never before understood it to be essential to a county town more than any other, that should be built upon the sand.

The Remonstrance also pointed out how Flemington was far more centrally located than Lambertville was. The County had a north-south length of 42 miles, with Flemington being “at least 12 miles nearer” to the central point than Lambertville. When your mode of transportation is horse and buggy, every mile matters.

This was answered by “A Citizen of Lambertsville,” as the town was then called, noting that “I unhesitatingly aver, that a new court house, jail, and public offices can be erected at some thousands less expense at Lambertsville than at Flemington: this fact is so obvious as to defy refutation.” It’s not really all that obvious, but perhaps it had to do with the cost of transporting timbers.

The Assembly bill to hold a county election on the location of the county seat was reported out of committee for a vote, which took place on March 5th. It lost, by 22 to 21, a much closer vote than was predicted by Flemington’s supporters. The Gazette’s editor concluded: “The court house will of course be rebuilt at this place.”

Designing a Courthouse

As mentioned previously, the argument for avoiding a referendum was based on the claim that it could delay construction of the courthouse for up to two years. The Freeholders were not about to put up with that. This item appeared in the March 12th edition:

The Board of Chosen Freeholders for this county met in this place on Monday, and adjourned yesterday. We . . . learn incidentally, that they have resolved to proceed in the election of a Court House and Jail with convenient dispatch; and have made arrangements for obtaining the most eligible plan for the building. We understand they propose building on the site of the old house, by placing the Jail some distance in the rear, to be constructed of the stone now on the ground, and putting up a handsome brick edifice in front for the accommodation of the Courts – the whole to be removed a short distance back from the range of the main street. The board have appointed a committee to visit some other court houses recently erected in other counties in the state, with the view of getting a knowledge of the best models.

So the Freeholders had some idea of what they wanted in a new courthouse, but others also had opinions. In the March 26th edition, a person identifying himself as “Hunterdon” wrote to the Gazette, asking “What kind of men are most competent on a building committee for this purpose?”4

All will concede that the new edifice should be one that will comport with a population, wealth and comparative importance of the county of Hunterdon, and at the same time one that, in its accommodation and finish, will give an assurance of permanent location, and be in accordance with the taste of the age in which it is constructed.

There are few men who have architectural gift beyond the common order. That talent is a rare one, and much sought after in our country: and without any disparagement to a good practical building talent, the latter is not sufficient to unite convenience with permanency, taste, and elegance in structure.

If this be so, would it not be advisable for the board, at their next meeting, to institute a correspondence with Mr. Stricklund or Mr. Haviland, two of the first architects and designers in our country, and obtain from them a draft of such a building as may be proposed. These gentlemen have given assurances of their talent in the beautiful structures which we find in the principal cities of our country; and that their draft would be such as good mechanics could readily work after – it would facilitate the labors of the committee while the building is erecting, and it would prevent some of those strange blunders which sometimes occur when a building is more than half finished.

The architects that the writer named were most likely William Strickland and John Haviland. Strickland, born 1788 in Middletown Twp., NJ, was a prominent Philadelphia architect who often worked “in the Greek style.” Haviland, born 1792 in England but also a Philadelphia resident, was “a major figure in American Neo-Classical architecture, author of The Builder’s Assistant, an important early book on American architecture. Did either of them contribute plans for the courthouse? The results suggest that one of them did. Mr. “Hunterdon” continued:

The expense of this draft would not, in all probability, exceed the sum of $100, which in a building that in the whole will not exceed the sum of $20,000, is a matter of no moment. . . . Our county begins to feel its comparative importance; and when it is known that Monmouth, Burlington, Warren, Morris and others, have public buildings which are the pride of these counties, Hunterdon is not disposed to fall below them in a liberal appropriation for this purpose.

With respect to the committee, all I will say, Sir, is – shew me three man of integrity, who have the qualifications of experience, judgment, industry, taste, liberality, and a spice of that principle called expedition, and you have my man.

[signed] Hunterdon.

Although the names of those who did the actual construction are probably tucked away in a file somewhere, at least we know who one of the stone masons was: John E. Trimmer. This according to Frank Burd who wrote his recollections of the Courthouse in the Hunterdon Historical Newsletter.5 John E. Trimmer (1790-1880), son of Herbert Trimmer and Maria/Martha Thatcher, married Elizabeth Smith in 1814 and had eight children, from 1815 to 1835. The family lived in the vicinity of the Gary Rake Factory, up in “The Swamp.” (Egbert T. Bush wrote that he lived a half mile east of the Frog Tavern.) According to Mr. Burd, in his later years, Trimmer would come to town and point at the building, saying to anyone passing by, “I carried up the southeast corner of that building and there she still stands just as plumb as the day she was laid up.”

Perhaps Mr. Burd got the story from Egbert T. Bush who wrote:

John E. Trimmer should be remembered as a mason who, in 1828, carried up one corner of the now famous Hunterdon County Court House at Flemington. I used to enjoy hearing him tell about walking to and from the job. How proud of his good work he seemed to be! “There it stands, perfect to this day,” was a favorite ending to the tale. One can scarcely help wishing that he could see that corner and its surroundings now but perhaps it is better otherwise. Nothing but that perpendicular corner would be real to him.6

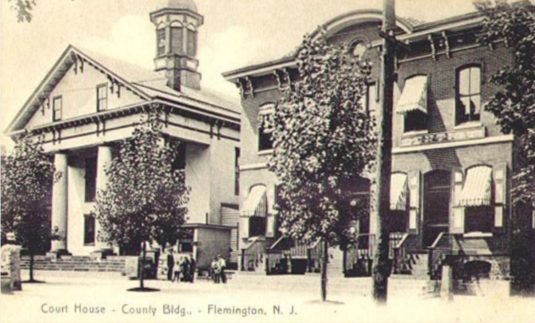

According to Frank Burd, in his youth (c.1900), the first floor of the courthouse was used as the county jail. Court was held on the second floor, the floor with the high ceilings. The frame building connected on the side (which can barely be seen in the photo below, provided by Richard Higgins on Facebook) was the jail kitchen. Also accommodated in the building was the Sheriff’s office and living quarters for him and his family. But apparently the County Clerk had to live elsewhere. And there was also a law library, and room to sequester jurors.

It did not take long to decide on a design and an architect. On May 7, 1828, the cornerstone was laid “with considerable ceremony.” It contained a bible, a copy of the Laws of New Jersey, and a brass plate with the names of the architect and members of the building committee.7

One of the earliest descriptions of the new courthouse appeared in an advertisement in the Gazette by a young attorney named Samuel G. Opdycke.

“Ascending!

FINDING the room on the first floor of the Court House rather too much confined for an office, and the passage too much obstructed by lockage for the free ingress and egress of clients, I have selected, for a summer office, a beautiful airy chamber in the extreme front of the building. This pleasant apartment is situated immediately over the portico of this lofty edifice, and overlooks the main street of the village; After rising three inclined planes, clients will arrive at the summit level of my office; the door opens toward the east between two windows; No toll demanded until they arrive at the summit. – Passage back, free of expense; Samuel G. Opdycke, Flemington, May 19, 1830.”

Consequence of a Consequence

While the Freeholders were pondering the design of a new courthouse, another interesting development was taking place, probably triggered by the failure of the bill to vote on moving the county seat to Lambertville. On March 26, 1828, the Gazette reported that the Legislature received petitions from “Hunterdon, Somerset and Middlesex and Burlington in favor of a new county [Mercer], to be set off from parts of said counties.”

Apparently the petitions did not move the Legislature to draft a law creating a new county. The subject was left to ripen until 1833 when it came to the fore again. But it took another five years before the Legislature finally took action and created the County of Mercer. There was one intriguing item in the Gazette about the negotiations over the boundaries of the county.

The New County bill has passed the Assembly. We have not seen the bill; but we understand it takes from us all the township of Hopewell, with the exception of that fertile district which skirts Sourland Mountain, which may have been left to us for the purpose of becoming our seat of justice, in case the removal of our court-house shall ever become a question. This was very considerate and kind to Old Hunterdon.8

The Election of 1828

As the year progressed, another controversy took up space in the Gazette: the Presidential campaign of 1828, with “The Administration,” headed by John Quincy Adams, and the opposition, headed by Andrew Jackson. This was a very interesting period in American politics, when the political parties we are familiar with today had not yet taken shape. But this campaign was probably the fiercest that Hunterdon residents had ever experienced. It was so fierce that the Gazette’s editor felt obliged to publish this admonishment:

We wish our correspondents to bear in mind that we have not opened our columns to that illiberal cant which characterizes so much of the discussion (so called) of the presidential question. Nor are we willing to make them the medium of circulation to recriminatory remarks, by which the remnant of good feeling amongst us might be obliterated, and the asperity of party zealots unnecessarily indulged without the prospect of an equivalent advantage to the community, either present or future. With the imputation of ‘corruption’ in which one is so prone to dabble, we will have nothing to do, unless personal identity and positive proof be furnished to sustain its application. – A word to the wise ought to suffice, as we wish not to be more particular.9

Sound familiar?

By the end of 1828, the jail was just about completed, with space for “the accommodation of debtors. The Freeholders met for the first time in the new Courthouse at the end of March 1829. The cost of construction had been $13,513.86,”10 which was far less than the $20,000 anticipated.

The design speaks for itself, having a truly timeless quality. The actual construction must have been carefully done, as the building is still standing and still in use, 192 years later.

Footnotes:

- For an interesting discussion of construction of this original courthouse, see the Hunterdon Historical Newsletter, published by the Hunterdon Co. Historical Society, vol. 14, no. 1, Winter 1978, “Our Courthouse.” ↩

- I have written about Charles George in the past. See “Charles George & the Hunterdon Gazette” and “Chas. George & the Gazette, part two.” ↩

- Frank L. Greenagel, Less Stately Mansions, 2002, 2014, p. 266. ↩

- I cannot say who the members of the Building Committee were. The Gazette did not name them, nor did articles in the Hunterdon Historical Newsletter and Snell’s History of Hunterdon. I imagine the names can be found in the County Archives. ↩

- Frank Burd, “Our Courthouse,” HHN, Fall 1978, vol. 14, no. 3, p. 265-69. ↩

- E. T. Bush, “Father Abbey’s Will Peculiar Document,” Hunterdon Co. Democrat, March 11, 1937. Not sure what Bush meant by how the courthouse looked when he wrote this, but it was most likely a reference to the tumult created by the Lindbergh Trial in 1935. ↩

- Snell, Flemington Village, pp. 324-342. “The Courthouse,” p. 202. The chapter did not name the building committee or architect. ↩

- Hunterdon Gazette, February 7, 1838. ↩

- No. 184. Wednesday, September 24, 1828. ↩

- Hunterdon County webpage. ↩