Taylor and Bray, continued.

This is the third in a series of articles about the founding of the town of Clinton in 1828. The two men who made this happen, Archibald S. Taylor and John W. Bray, Jr., came to grief in a fairly short time. The Town succeeded, but the founders failed miserably, and their original friendship turned into a deep hostility. This article focuses on what happened to them after Bray’s misdeeds were discovered.1

The Outraged Sons

The behavior of John W. Bray following his bankruptcy outraged Taylor’s three sons: George W. Taylor (1808-1862), Lewis H. Taylor (1811-1908) and youngest son William J. Taylor (1815-1881). What offended them most was that Bray denied being the cause of their father’s ruin and could not be called to account in the legal system for the harm he had done, because A. S. Taylor refused to take Bray to court. Taylor, who shied away from appearing in public, reasoned that Bray was not able to restore the lost finances, so a trial was pointless and the exposure would be painful to him.

With legal recourse denied them, the sons took another approach. On October 27, 1835, the day that the sheriff’s sale of Taylor’s property was being held, they went searching for Bray in Elizabeth Town, where Bray was attending to the business of the Elizabeth & Somerville Railroad (of which he was one of the directors). When they found him crossing the main street, they knocked him over with a club and hit him several times while he was held down, and, according to the Newark Daily Advertiser, “cropped nearly two thirds of his right ear.”2 The paper reported that he was also stabbed several times in his right arm. This was done in broad daylight, in sight of witnesses. All of the Taylors were said to be armed with knives or pistols, and managed to escape before they could be arrested. Afterwards, their father wrote that this version of the attack was greatly exaggerated. (The Taylors’ version of the incident never got into print.)

The reporter explained that “these lawless youngsters” were seeking revenge for Bray’s involving his brother-in-law “by means of endorsements.” The editor wrote “we trust the public ear will be utterly closed to any flimsy pretence which may be urged in extenuation.” Apparently this sort of violent attack was not uncommon, and the writer felt it was time for the court to make an example of the Taylors.

Information about this attack and documents relating to the court case that followed came to me from John W. Kuhl. What first caught his attention was a version of the story published 48 years later, on August 13, 1883 in the Hunterdon County Democrat, quoting a writer in the Newark Advertiser, “whom we hope is truthful,” who “managed to pick up the gossip we never have seen in print or even hear of.” (If the Advertiser’s reporter had taken the trouble to search his paper’s back issues, he would have found a truer version of the story.)

“CUTTING OFF A NEGRO’S EAR. I passed the Taylor mansion which stands about a mile from Clinton. . . . My companion, an old resident of Somerset, told me that General [George W.] Taylor and his brother Lewis one day caught a negro on the road near New Brunswick, who was a great liar, and had formerly been in their employ; they took him and cut off one ear and let him go. They were indicted, but nothing further was ever done about it. A ‘nigger’s ear in those days was not of much consequence to courts when the question of the cost of trial was up.”

John Kuhl wrote that this bizarre version of the story shows “the danger of accepting newsprint as gospel,” but “that there is often a grain of truth in the most improbable of stories.”

Although intensely reluctant to appear in public, Archibald Taylor could not refrain from publishing a defense of his sons’ actions.3

TO THE PUBLIC. The undersigned, who is the father of the young men implicated in the late assault upon John W. Bray at Elizabeth Town, begs leave to address a few words to the public on that subject. It is not his intention to enter into a justification of the act—all he asks is, that the public will suspend their opinion as to the causes which led to it, until a publication can be made of the whole affair, when they will be able to judge for themselves, whether the aggravated and enormous wrongs sustained by an old, infirm and beloved father ; wrongs by which his sons have been goaded on to desperation, will not in some measure palliate their deed. For his own part, altho’ he has been hurled from affluence to poverty and dependance, and is now in his old age, and in the midst of his many infirmities, compelled to abandon his hearthstone to strangers and to quit the scene of all his former happiness, the birthplace of his children (one of whom died in the service of his country) and where every tree and every bush shares in his affection from having been planted and reared by his own hand; yet not withstanding all this, he desired no revenge, but was willing to leave the author of all his accumulated ills to the dealings of his own conscience and the justice of his Maker. The only object of this publication, he again remarks, is to solicit from the public a suspension of opinion until they know all. Where himself and his misfortunes are known, and where the hitherto unreproachable character of his sons is known, he feels confident that this appeal is now [un]necessary—It is to those at a distance, who know nothing, or whose ears have been poisoned by false accounts, that it is more particularly addressed. It is hardly necessary to say, that the published accounts of the assault are greatly exaggerated. [signed] Archibald S. Taylor, Lebanon, Hunterdon County, NJ.

The child who “died in the service of his country was Robert, a midshipman in the U. S. Navy, who died from yellow fever in 1823, at Key West, Florida. Taylor wrote “A publication . . . of the whole affair” in a long memorandum which I quoted from extensively in my previous articles. Unfortunately, it was not dated, and never appeared in print. He wrote it in order that “the foul aspersions which John W. Bray has sought to throw upon my integrity may be repelled and his conduct exposed to the odium it deserves.” Bray responded to Taylor’s “card” in a way that shows what sort of person he was, given so much evidence against him. He was living in Elizabethtown at that time. His reply was published in the Hunterdon Gazette on Dec. 2, 1835:

A WORD IN REPLY. In relation to the foregoing card [A. S. Taylor’s statement above] . . . the undersigned deems it necessary at this time only to oppose his unqualified denial to the gratuitous and injurious implication of his being “the author of all Mr. Taylor’s accumulated ills.” The insinuation is not true and in thus appealing to the sympathies of the public, Mr. Taylor has drawn largely upon his imagination for the purpose of averting just indignation towards his sons for their gross and brutal attack upon my person. The picture of his former affluence and present poverty is altogether exaggerated. Since, however, he has chosen to make the public a party to our private transactions, I propose to meet him at once on equal terms, and hereby offer to submit with him the whole history of our business intercourse to the arbitration of the Hon. Messrs. Frelinghuysen, Southard and Wall, and to abide by their decision.

This proposal was rejected by Taylor, who replied “there are no matters open between John W. Bray and myself of a nature to render an arbitration either necessary or proper.” And Bray replied to that statement by observing that “honorable men must of course regard [Taylor’s] ex parte assertions as the unauthorized abuse of a conscious slanderer.”4

The Legal Outcome

Soon after this, the Mayor of the Borough of Elizabeth offered a reward of $300 for the capture of George W. Taylor so that “he may be proceeded against upon the indictment found against him.” The notice described Taylor very carefully (I suspect it was written by John W. Bray):

George W. Taylor, formerly a midshipman, about 27 years of age, about 5 feet 9 inches in height, thick and rather curly black hair, heavy eyebrows, sharp black eyes, rather sunken in the head, with Whiskers, but probably they may be cut off, rather thin face, good person, genteel looking, with rather a dandy walk, has some marks with India ink on his arm or arms, the marks supposed to be of a naval character, dresses quite genteel, and has been in the habit of wearing a Spanish cloak made of olive cloth; he has usually put up at the American Hotel when in the city, it is believed that he will sail in some vessel for New Orleans, the West Indies, or Texas.5

All three sons were eventually arrested for their crime; they posted bail of $2,000 each and pleaded not guilty. The trial was held on April 14, 1836. The jury

“found the defendant George W. Taylor Guilty in manner and form as he stands charge in the second count in the Indictments against him and not Guilty upon the other counts in the said indictments and they find the defendants William J. Taylor and Lewis H. Taylor Guilty in manner and form as they stand charge upon the fourth count in the respective Indictments against them, not guilty in the other counts in said Indictment and so they say all and the Jury further recommended each of the said defendants to the mercy of the court.”6

The court did show mercy. In 1837 George W. Taylor appeared before the Court of Pardons, which consisted of the Governor and Council. This was back when the judiciary and the executive branches were not so clearly separated as they are today. The Court “remitted the imprisonment” that Taylor had been sentenced to, which was a mere twenty days. The Gazette announced this ruling on June 7, 1837, saying “The very great mitigating circumstances of this case, particularly the fact that the assault originated in no personal feeling, but from the injuries and injustice suffered by the father of the defendant, called for an unusual degree of lenity from the court.”

The expression “no personal feeling” seems not quite accurate—I image there was a lot of personal animosity toward Bray in the Taylor family. Apparently the plea by the Newark Daily Advertiser that the Taylor boys be given harsh sentences and made an example of fell on deaf ears. The verdict by the Court of Pardons seemed to show that Archibald Taylor had succeeded in creating sympathy for his plight and a consensus that Bray had greatly wronged him.

Postscript for John W. Bray

John W. Bray was never called to account for the disaster he created for his investors. (A. S. Taylor was not the only one who suffered from Bray’s folly.) However, he did get indicted for one particular offense—forgery. In 1836, John W. Bray was accused of forging the signature of his former friend, Asa C. Dunham, on a note given to the Easton bank. It was honored and thereby caused Dunham to go bankrupt. In fact, in late 1835, Dunham was imprisoned for debt.

The forgery trial, known as The State v. John W. Bray was held in the Hunterdon circuit of the Chancery Court, the Chief Justice presiding. The jurors chosen were Edward Welsted, James Waterhouse, Foster Vankirk, Peter H. Huffman, Jacob Johnston, Thomas Langstroth, John P. Yawger, Israel Smith, David Rockafellar, L. R. Titus, Peter Haver, and Stacy A. Paxson.

A very odd notice was published in the Newark Daily Advertiser on Nov. 1, 2, & 3, 1836, and the Hunterdon Gazette, Nov. 2d:

The subscribers, the Jurors empannelled, sworn and affirmed, for the trial of this Indictment, deem it proper to state, that the investigation of the case, upon the evidence, resulted in the unhesitating conviction, in their minds, of the entire innocence of the Defendant, of the charge brought against him,–and that there did not appear, upon the trial, the slightest ground to believe him guilty thereof. Flemington Oct. 27, 1836.

I have never seen a statement quite like this in the Hunterdon Gazette. It makes me wonder if John W. Bray did not have something to do with its publication. Asa Dunham was certainly not happy about the verdict. Here is his response:

TO THE PUBLIC. I HAVE seen with great surprise a statement signed by the jurors empanneled [sic] to try the indictment found by the grand jury of Hunterdon county against John W. Bray, for forgery. Had this statement been simply published without remark, I should have let the matter rest where the jury left it, but the defendant having seen fit to give it a caption in some of the papers where it has been inserted, evidently aimed injuriously at me, I have thought proper to place before the public the evidence submitted to the jury by the State.

I made application to the prosecuting attorney, William Halsted, Esq. for the notes of the evidence as taken by him at the trial, intending to publish it entirely, but was informed by him that they had been mislaid, and I am therefore obliged as the next and only resource, to publish the affidavits of the witnesses for the state sworn at the trial.

The only rebutting evidence offered by the defendant was that of Mr. John B. Taylor, his son-in-law, and partner in business at the time the note alleged to be a forgery was given, and of Mr. Howel, a clerk in the Easton Bank, who both stated that they believed the signature to be genuine. My own evidence was not admitted, being excluded by an old rule of law, which the chief justice stated that he himself was in favor of breaking down, but that as his associates were not on the bench, and as it was a circuit, he would not venture to do it alone, although in his opinion the rule was absurd, and often favored the escape of the offenders from justice.

The truth is, however, that no evidence would have been sufficient to ensure a conviction, as there was a capital defect to the indictment, which, the moment it was pointed out by the defendant’s counsel, induced the Court to put a stop to the proceedings and charge the jury to find the prisoner not guilty. [signed] Asa C. Dunham.7

The depositions were taken on Nov. 21, 1836 before Richard Coxe, Esq. As Dunham wrote, this step was necessary because the prosecutor had “mislaid” his notes. The deponents were his brother Azariah C. Dunham, Jonathan M. Welsted, Robert Foster, James R. Dunham and Alexander Bonnell, all well-regarded citizens of the neighborhood of Clinton.8 All of them stated that they knew the handwriting of Asa C. Dunham, and that the signature on the note was not his. Azariah Dunham, Jonathan M. Welsted and James R. Dunham also knew the handwriting of John W. Bray and deposed that the signature purporting to be that of Asa C. Dunham was written by Bray. When Alexander Bonnell was shown several signatures on notes given by the cashier of the Easton Bank, he quickly identified the one that was claimed to be the forgery.

Soon after this case was tried, John W. Bray, Jr. left New Jersey altogether. He appeared in the 1840 census living in Lafayette Co., Missouri with wife Mary and children, and a female in her 50s (most likely his mother-in-law, Mary Newell Grandin). He was still there in 1850, when he was 62 years old, working as a clerk, and living in the household of his son John G. Bray, a 36-year-old merchant, and his wife Frances. By 1870, the whole family had moved to Santa Clara County, California where Bray died on April 22, 1866, age 77.

Archibald S. Taylor’s Last Days

Although A. S. Taylor wrote that he was forced to abandon his hearthstone to strangers, I am not certain that that actually happened. After the courts had finished sorting out the debts incurred by John W. Bray, Archibald S. Taylor was able to return to his hearthstone.

Taylor’s assignees did put the property up for public sale on October 27, 1835. But there were complications, inasmuch as Taylor owned the property jointly with this brother John Allen Taylor, who resided in New York.9 This matter was still being sorted out in the 1850s when the two families sought for a partition of the property by the N. J. State Senate.10

Taylor was living with his son Lewis H. Taylor and family when the 1840 census for Lebanon Township was taken. It identified Lewis H. Taylor as head of household, in his 20s; living with him, along with wife and children, was an unnamed male in his 50s. (The 1840 census only named the heads of household.)

In 1849, George and Lewis Taylor were enticed to try their hands in the Gold Rush in California, probably in an attempt to restore their finances. This is born out by the census of 1850, which shows Archibald Taylor age 69 living with daughter-in-law Jane C. Taylor (wife of Lewis H. Taylor), age 37, and her children. Also in the household was Archibald Taylor’s youngest son William Johnston Taylor, who was an unmarried physician, age 35.11

Archibald S. Taylor wrote his will on August 17, 1854 at which time he was “of the Township of Clinton.” He named his sons George W. Taylor and Lewis H. Taylor his executors, so it is most likely they had returned from California by then. He also named his daughter Sarah Ann, wife of James R. Dunham, and his grandsons George and Archibald, sons of Lewis, both minors. The will was witnessed by William S. and Sylvester Seal. Archibald Taylor died on May 9, 1860 at his home, ‘Solitude’.

Taylor’s obituary appeared in the Hunterdon Republican on May 18, 1860. It is fascinating, not for what it says about Taylor so much, as for its description of life at Solitude House during the Revolution, so I am giving it here in its entirety:

DIED

At his residence, Solitude House, near High Bridge, Hunterdon County, N. J., May 9th, 1860, Archibald S. Taylor.

The deceased would have attained the age of 79 years had he lived until the 29th inst. His father, Robert Taylor, who died in the same house, and at nearly the same age, was born in County Londonderry, Ireland, in 1742, and died in 1821.

Archibald S. Taylor was familiar by tradition, as well as by personal knowledge, with the early history and residents of this county. He well remembered Brigadier General Maxwell, who made frequent and long visits at his father’s residence, and he could relate some droll anecdotes of this rough and brave old veteran of the Revolution. He also well remembered Colonel Stewart, A. A., Commissary General of Washington’s Army, whose place of residence was the Union Farm for some time during and after the Revolutionary struggle. He also remembered Colonel Aaron Burr, who visited his father’s when the subject of this notice was a boy. Col. Burr’s daughter Theodosia, afterward Mrs. Allston, (whose mysterious fate has never been revealed,) was at that time a visitor in the neighborhood.

Governor John Penn was for some time a resident (by compulsion) of the Solitude House, when occupied by Robert Taylor. Being inimical to the revolutionary movement, he was required by the Continental Congress to give his parole of honor, and retire to the interior, a State prisoner. He remained at the Solitude House for some time on his parole, in company with Benjamin Chew, Esq., who at the breaking out of the war was one of His Majesty’s Provincial Council for the Colony of Pennsylvania, and a large land-holder both in New Jersey and Pa.

The deceased has frequently of late expressed his conviction that he would not live through the Spring. He had marked symptoms of paralysis and apoplexy; but he looked to the end with rare composure and even cheerfulness. Soon after he was struck down, he fell into a deep sleep from which he never aroused, and apparently free from pain, died without a struggle. His mortal remains were interred in the Cemetery of the Presbyterian Church at Clinton, attended by a large concourse of truly mourning relatives, friends and neighbors, including a full score of aged men who had known and esteemed him more than half a century.

Of his cultivated mind, refined manners, and generous heart, all who knew him can testify with sad and cherished memories. Then like our dear departed friend, do thou, O reader,

“So live, that, when thy summons comes to join

The innumerable caravan, that moves

To that mysterious realm, where each shall take

His chamber in the silent halls of death,

Thou * * * * sustained and soothed

By an unfaltering trust, approach thy grave,

Like one who wraps the drapery of his couch

About him, and lies down to pleasant dreams.”

Philadelphia, May 14, 1860 [signed] T. T. J.12

It is interesting that the very public scandal that Taylor lived through got no mention. But this was the Victorian era, and that sort of thing was just not discussed in obituaries. Instead, the writer dwelled at length on Revolutionary War associations. In light of the attention being paid recently to the life of Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr, this visit from Burr is most interesting. I assume that since A. S. Taylor was “but a boy,” the visit probably took place before the duel with Hamilton.

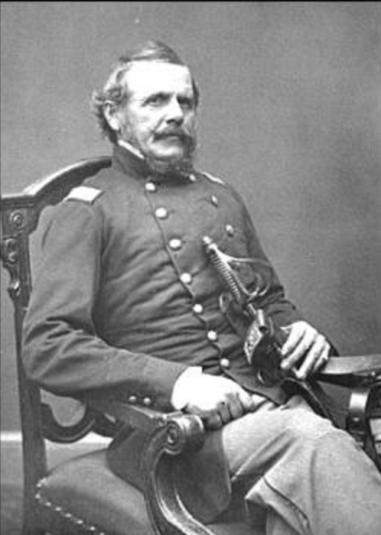

Taylor was spared the agony of a parent whose sons went to war. His third son, George W. Taylor, became a brigadier general and died on September 1, 1862. In the story of 1883, quoted above, the author wrote:

It will be remembered that General George Taylor was killed at the second battle of Bull Run. His courage and character are commemorated by a beautiful monument in the Clinton cemetery surrounded by a statue of Liberty.13

Footnotes:

- This article probably won’t make much sense unless you’ve read the previous one: “The Ruin of A. S. Taylor.” And that one will make more sense if you have read part one: “The Town of Clinton.” ↩

- Newark Daily Advertiser, Oct. 28, 1835, p.2. ↩

- It appeared in the Hunterdon Gazette on Nov. 18, 1835, and also in the Newark Daily Advertiser on Dec. 2, 1835. ↩

- Newark Daily Advertiser, Nov. 24 and 27, 1835. ↩

- Hunterdon Gazette, Dec. 2, 1835. ↩

- Court of Oyer & Terminer, Essex County, April 1836. ↩

- Hunterdon Gazette, Dec. 7, 1836. ↩

- A brief genealogical note: James Dunham (1754-1820) and Mary Elizabeth Cathcart (1760-1803) had sons Asa C. Dunham (1795-1876), Nehemiah Dunham (1797-1876), Aaron Dunham (1799-1825) and Azariah W. Dunham (1802-1863). They were grandsons of Hon. Nehemiah Dunham (1721-1802) and Mary Clarkson. James R. Dunham (1812-1875) was the son of Jacob Dunham MD and Elizabeth Lawson, and grandson of Azariah Dunham (1719-1790) and Mary Stone Ford (1730-1819). ↩

- To find out what happened to the Solitude House property, it is necessary to examine court papers on file at the Hunterdon County Archives, which I have not done. ↩

- See Senate Journal, 1851, pp. 209, 212. ↩

- Wm. Johnston Taylor is said to have married Jane Taylor Taitt, daughter of Samuel Taitt and Charlotte Johnston, but the Hunterdon Republican reported in 1859 that he had married Ella Knight, daughter of Samuel Knight, Esq. That marriage took place in Philadelphia, where Wm. Taylor spent the rest of his life. ↩

- The poem is Thanatopsis, by Wm. Cullen Bryant, written about 1810-15. The words that were left out were: Thou “go not, like the quarry-slave at night, Scourged to his dungeon, but,” . . . I have not succeeded in identifying who T. T. J. was, but he may have been related to Jane Crow Johnston, wife of A. S. Taylor’s son Lewis H. Taylor. Jane Johnston Taylor’s father was William Phillip Johnston (1767-1846) but I have not been able to identify his other children. ↩

- An excellent article, written by John W. Kuhl, on G. W. Taylor’s military career can by found in the Hunterdon Historical Newsletter, Winter 1980, p. 299. ↩

William Honachefsky Jr

August 7, 2016 @ 1:29 am

Well Done

Marfy Goodspeed

August 7, 2016 @ 8:05 am

Thank you, Bill.

Stephanie Stevens

August 8, 2016 @ 1:15 pm

Nice job, Marfy –

People just don’t change , do they?

Doreen Grieve

August 9, 2016 @ 4:16 pm

It is amazing how you can read through all the very dry and disconnected buried information and pull together a story that is interesting, enlightening and gives us a very realistic look at our past. Thank you!