Hunterdon County probably holds the record for the most 19th century iron truss bridges that are still in use. In Delaware Township alone there are nine iron truss bridges, not including the Covered Bridge, which is also a truss bridge. The most important of these iron truss bridges is the one crossing the Lockatong Creek on Rosemont-Raven Rock Road. That bridge is an outstanding example of the urge to lend some grandeur to a very functional structure. None of the other township bridges quite matches it.

There is another one almost as good crossing the Lockatong Creek on Strimples Mill Road. It was built in 1897 by the Wrought Iron Bridge Co. of Canton, Ohio, and seems to have been designed to mimic the more elaborate bridge nearby.1

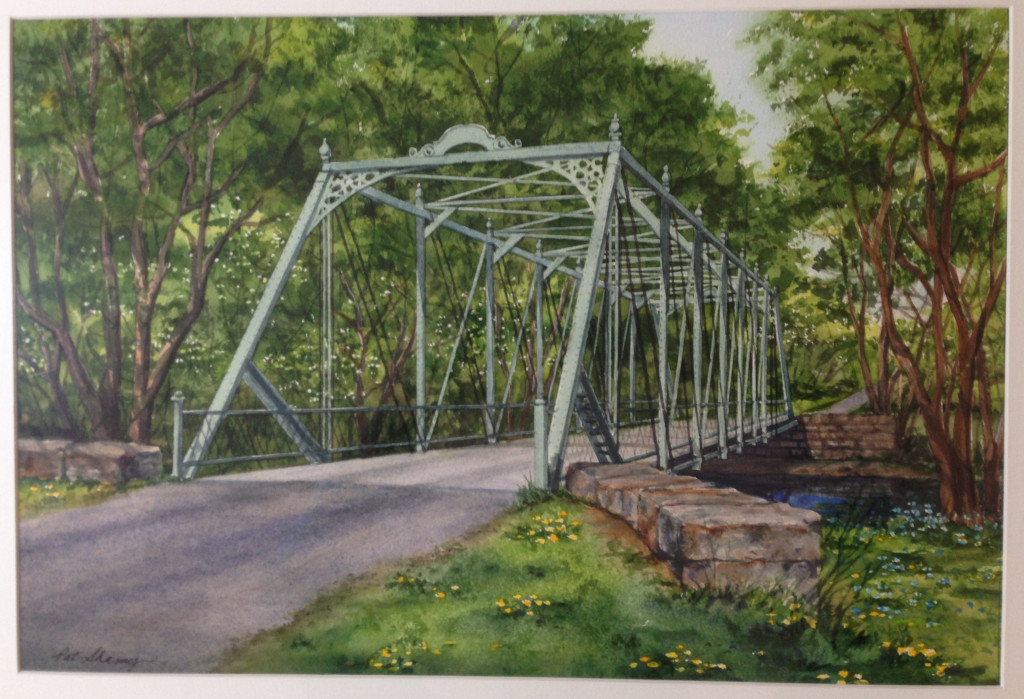

The bridge on Raven Rock Road has gotten some attention this year because the County acquired a grant to take it apart and put it back together in order to improve its carrying capacity and repair damage to the structure over the years. Despite the care that has been taken, the bridge will never look quite the same again. Thanks to Pat Shamy who made a lovely water color of the bridge several years ago, I have a way to remember how it once looked.2

It must be said that the County did take special care to maintain as much of the original structure as possible. However, the county engineer insisted that guide rails must be added on the inside of the metal trusses, and that changes the look of the bridge significantly. But at least they did not widen the roadway, as they have done in most other cases. Recently, an article about the bridge and the work being done on it was published in the Hunterdon Democrat, by long-time reporter Terry Wright. It is an excellent story, and if you missed it, you can find it here on NJ.com.

A few years ago, an application was made to put this bridge on the National Register of Historic Places. The application was prepared by Barbara Plunkett in 2005. Although it did not get all the way through the approval process, the county road department treated the bridge as if it were actually listed on the Register. Even an engineer can tell that this bridge is something special.

The bridge was re-opened for business this past month, but soon afterwards, a crack in the new work was discovered and the bridge was closed on July 29th. The engineers are taking no chances. It is fervently hoped that the bridge will again be open in time for a celebration in September. In the meantime, I’ve been learning about the people and companies involved in its construction.3

The Lambertville Iron Works

featuring John Laver, William Cowin and William Johnson

To understand how the Raven Rock Road Bridge came to be built, we must learn about the lives of William Cowin and John Laver. This may seem odd because neither of them were alive when the bridge was built. But their company, the Lambertville Iron Works, got the contract for the bridge, and that would not have happened unless Laver and Cowin had established a company that the freeholders could trust.

Most articles describing this company state that it was organized in 1849 as the partnership of Laver & Cowin. The source for this date appears to be the article on Lambertville in Snell’s History of Hunterdon County (p. 283). This date got repeated in Hubert G. Schmidt’s Rural Hunterdon (p. 219), and in Iris H. Naylor’s “City firm built Lockatong Creek bridge,” a column published in “The Beacon” of Lambertville in 1997. It also showed up in the New Jersey Historic Bridge Survey compiled by A. G. Lichstenstein. But a little digging has shown that the date is wrong. Here is the history that I have found.

Laver & Cowin

John Laver and William Cowin Jr. established the partnership of “Laver & Cowin” in 1857. Both men were born in England, and were present in Lambertville when the census of 1850 was made.

William Cowin was born in Yorkshire, England on March 19, 1825.4 He was the son of William Cowin Sr. and Sarah Mackin and emigrated with them to America about 1849, when he was 24. Cowin’s obituary states that he came to America in 1849. He was naturalized on Sept. 24, 1852.5

When the family was counted in the 1850 census for Lambertville, William Cowin Sr. was a 48-year-old “moulder,” and his wife Sarah was 47. Living with them was Sarah’s father, Charles Mackin, age 69, as well as their children, William 25, working as a “pattern maker,” Eliza 20, Charles 11 (born in Pennsylvania), and Frances 6 (born in NJ, about 1844).6

As a “moulder,” William Cowin Sr. poured moulten iron into various molds; in other words, he was making items of cast iron. His son the “pattern maker” was employed in designing the mold that would be used.7 All kinds of machinery and building elements made of iron had to go through this process. The railroads were just beginning to be built at this time, and demand for machinery was ratcheting up. New techniques for producing cast iron were developing, along with a better understanding of the properties of both cast iron and wrought iron, which will be discussed further in part two of this story. With these kinds of skills, the Cowins were very desirable immigrants.

John Laver was born in England in 1807, but was present for the Lambertville census of 1850, when he was 43 years old, also identified as a “moulder,” like William Cowin Sr. I suspect that the Laver and Cowin families came to America together because John Laver was married to Hannah Mackin, the daughter of Charles Mackin, and sister of Sarah Mackin, wife of William Cowin. Hannah Mackin Laver was born in England in 1805, and died on April 26, 1854. It is likely that John Laver and Hannah Mackin married in England; there is no record of their marriage in New Jersey. The 1850 census for Lambertville also showed that Elizabeth Mackin, age 40, and Emmala Cowen, age 8, both born England, were living with the Lavers. Elizabeth was almost certainly another daughter of Charles Mackin; she apparently never married. Emmala may have been the daughter of Sarah and William Cowin, but she did not appear in the census for 1860.

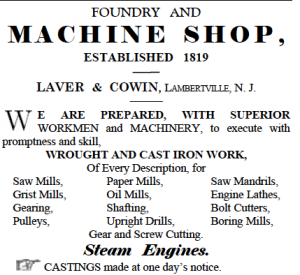

John Laver operated a foundry in Lambertville that had been in business since 1819,8 and it seems likely William Cowin, Sr. and Jr., found employment there. Certainly William Cowin Jr. made a positive impression on his uncle John Laver, for by July 1857, the two had joined in a partnership known as Laver & Cowin of Lambertville. They published an advertisement on July 1st as depicted in Bill Hartman’s compilations of the Hunterdon Gazette:

I am fairly certain it was William Cowin Jr. who partnered with John Laver, rather than his father. In 1857, William Sr. was 55 years old, John Laver was 50, and William Cowin Jr. was 32. William Sr. must have died between 1850 and 1860, for he is missing from the census of 1860.

1857 was the year that the area of Lambertville around Union Street, Jefferson St., Clinton Street and what was called Delaware Avenue (now Delaware St.) was being developed, after a ruling by James Wilson Esq., master of chancery, on the estate of John Holcombe dec’d. Union Street was being extended north. Two new streets were Jefferson St. (originally called Washington Street) and Clinton Street, “an extension of Canal Street.”9 This was where Cowin & Laver bought property.

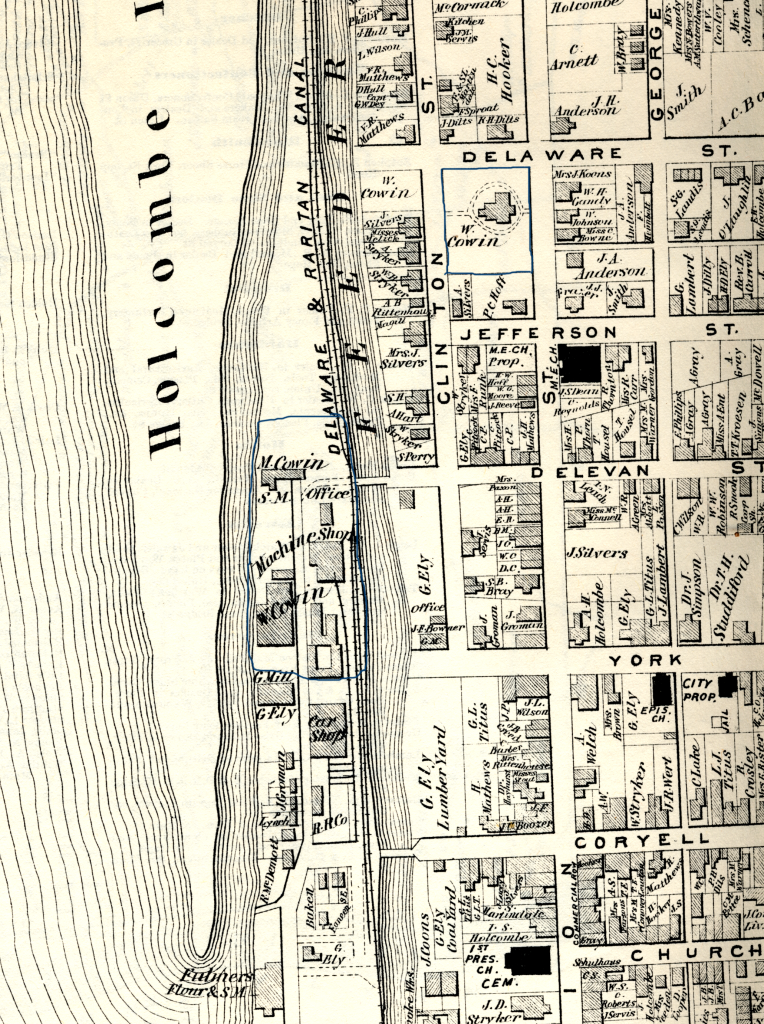

In March 1853, Laver & Cowin purchased two of the many lots of land in Lambertville owned by John Coryell. In June 1856 they bought another lot from Coryell, and again in 1858.10 They also purchased a lot from what had been land of John Holcombe in the same vicinity.11 By that time, the Belvidere-Delaware Railroad had been built parallel to the D&R Canal, and machine shops had sprung up along the tracks to build locomotives and railroad cars and maintain them.12 This is where Laver & Cowin set up shop, as shown in the 1873 Beers & Comstock Atlas of Hunterdon County (look for “Wm Cowin” along the canal, and for his handsome house at Delaware St. and North Union):

I have lightly outlined in blue the location of William Cowin’s home and of the Lambertville Iron Works, which were designated on the map as “W. Cowin.”

By 1858, when he was 33, William Cowin was making a name for himself in Lambertville. On April 21st of that year, he was elected as one of the town’s “Counselors.” At the same time, John Laver was chosen to be one of the Inspectors of Elections. On Jan. 19, 1859, William Cowin was elected treasurer of the Lambertville Building and Loan Association.

The partnership of Laver & Cowin did not last long. It came to an end in February 1859, when William Cowin paid $10,000 to buy out John Laver’s interest in the real estate they held jointly. The deed was dated February 16, 1859, and the property consisted of several lots amounting to 2.48 acres which Laver and Cowin had purchased jointly from John Coryell.13 An announcement of the end of the partnership was published in March:

Dissolution of Partnership. Notice is hereby given that the partnership heretofore existing between the subscribers, under the firm of Laver & Cowin, is by mutual consent, this day dissolved. All the business of the late firm will be settled by Wm. Cowin. [signed] John Laver, Wm. Cowin, Lambertville, Feb. 16, ’59.14

Most likely the reason for the dissolution was that John Laver was ill. He died four months later, on June 10, 1859. His wife Hannah had predeceased him, dying on April 26, 1854. The Lavers were buried at the Mt. Hope Cemetery in Lambertville.15

John Laver wrote his will on April 6, 1859, leaving bequests to Miss Emily Laver Makin (perhaps his daughter?) and to his sister-in-law Miss Betsey Makin ($2500 each), and also to Betsey Makin his half share of the house he was living in in Lambertville.16 He left $100 to Charles Makin, probably his father-in-law. He ordered his executor to sell his 25 shares of capital stock of the Lambertville Bank and distribute the proceeds, after paying funeral expenses and other debts, to people whose names I could barely read: Mrs Clara Cowen Wells, Mrs Claice{?} Makin Wells, Mrs Emily Seymour {?}, Miss Francis Angel{?} Cowin and Charles Makin Cowin. The will was recorded on July 7, 1859 when it was sworn to by the executor, George Gaddis.17 The Inventory taken on July 1, 1859 by John Runk and Ingham Coryell totaled $10,720., of which $10,000 consisted of a bond & mortgage given to Laver by William Cowin on February 16, 1859.18 The furnishings were typical of a Victorian brownstone, with front and back parlor, kitchen, bedrooms, stair hall, office. The item I am most fond of is the “Wat Not” in the front parlor, worth $5. It may have been a piece of furniture designed to hold what we would now call “what-nots,” or it could have been some objet d’art, probably sitting on the next item on the list, a marble-top table valued at $10. Also listed were 5 shares in the Lambertville Gass {sic} Company, but there was nothing related to Cowin’s foundry company (later to be known as Lambertville Iron Works).

John Laver’s estate was managed by his executor, George W. Gaddis, one-time tavern owner at Sergeantsville who moved to Lambertville about 1850, to continue as an innkeeper there. He was identified as such in the 1860 census, age 53, living with wife Lorania, and their six children. I am surprised that Laver chose Gaddis to be his executor, rather than his former partner and nephew, William Cowin. Perhaps that was because Cowin owed money to Laver.

In July 1859, Gaddis applied to bar creditors from making claims against the estate of John Laver. It is surprising that the estate was not sufficient to pay its debts, given that William Cowin had given Laver a mortgage of $10,000.

Cowin & Cowin

Along with the announcement in March 1859 of the dissolution of the partnership of Laver & Cowin was this addendum:

The Foundry and Machine business hereafter, will be continued at the old stand in Lambertville by the subscribers, Wm. & Chas. Cowin. Lambertville, Mar. 30, ’59.19

This Charles Cowin was the brother of William Cowin. He was born on Dec. 20, 1832.20 Possibly the first big job for this new operation came along on May 10, 1859, when the Board of Freeholders met at Moore’s Hotel in Lambertville and ordered a bridge contract to William and Charles Cowin, to build a bridge over Swan Creek where it crossed Union Street. As seen in the earlier advertisement by Laver & Cowin, bridge building was not on their agenda. But technology had changed by this time, making bridges built of both cast and wrought iron far superior to the old wooden bridges, and William Cowin was ready to take advantage of that development.

Once again, this partnership was tragically short-lived, as was Charles Cowin himself. Only six months after the partnership was announced, Charles Cowin was dead.

Death from Tetanus. On 13 Sept. 1859, Charles Cowin of Lambertville, aged 26 years, 8 months and 24 days. Mr. Cowin was returning from a hunting trip on 11 Sept., when his horse became frightened and started to run. The horse then kicked the front of the wagon and struck Mr. Cowin on the leg. He was brought home and treated but Tetanus developed and death resulted.21

This must have been a devastating set-back for William Cowin, at least personally. It does not seem to have hurt his business operations. By 1860 he was a wealthy man, having real estate worth $9,600 and personal property worth $13,000.22 At this time he was 35 and still single; his occupation was “foundry & machinist.” Living with him were his mother Sarah age 57, his grandfather Charles Makin age 78, and his sister Fanny, age 17. Missing from the household was William’s father, William Cowin Sr., who must have died sometime in the 1850s. (I have not found an obituary for him, but there might be a record in the NJ Vital Records.)

In 1860, William Cowin was elected to the Lambertville town council. But during the Civil War, he stayed out of politics. But he he did pay his taxes, which were substantial given his business success. He was taxed on a carriage, a piano and a watch; taxed on income of $4,400 and $2,638 (two separate businesses ?), and taxed as a manufacturer. But he did not serve in the military. Cowin was a Democrat. He was a delegate to Democratic conventions in 1860 and 1861, so he was probably not sympathetic with “Lincoln’s War.” He apparently was not subjected to the draft.

Up until 1864, William Cowin remained a bachelor. But that year, on May 3rd, he married Caroline Corson Welch (1840-1918), the daughter of renowned engineer and builder, Ashbel Welch. Since William Cowin and Ashbel Welch were both very prominent in Lambertville and both in related lines of work and active in Lambertville’s civic affairs, it is not surprising that they became acquainted. It is somewhat surprising that Cowin married a woman who was 15 years his junior, but that was not unheard of. They had two children, Lucy, born March 1865, and Walter, born June 14, 1867.

Most likely it was at this time that William Cowin built his ‘stately mansion’ at the corner of North Union and Delaware Streets. It was (and still is) a house designed to reflect the social status of this very successful man.

After the Civil War ended, Cowin again entered politics. In 1866 he was elected to the town council, and in 1867 was elected Mayor of Lambertville. This only lasted one year. In 1868, the new mayor was Joseph H. Boozer, who will appear in part two of this story.23

Sometime between 1859 and 1866, Cowin established his business under the name of Lambertville Iron Works. This name was being used as early as 1866, when the company appeared in the New Jersey State Business Directory for that year. The company was listed under “iron works” and under “iron founders, forges etc.” It advertised “all kinds of iron work,” including coal and freight cars and iron bridges (my emphasis).24

William Johnson’s Patent

Listed next to the Cowin family in the 1860 census was William Johnson (family #320-332), age 29, born in New York State, who was working as a machinist. I have little doubt he was employed by William Cowin since Johnson later became general manager of the company. Johnson’s real estate was worth $3,500 and his personal property was only $200. He was living with his wife Sarah 26 (born in England about 1834), their daughter Sarah F. age 7, born in New York, and son William age 2, born in New Jersey. The Johnsons may have come from the same part of England as the Lavers and Cowins. They were not related to the old Hunterdon Johnson family who owned large acreage near Raven Rock.

William Johnson was present in Lambertville by June 1, 1857, when he bought a lot from John Silvers.25 This was located in the new area of Lambertville that was opening up, along North Union Street and was adjacent to the lot where William Cowin built his grand house. There cannot have been a house on the lot of 0.32 acres at the time because it cost only $385. The fact that William Johnson was setting up in Lambertville by 1857 makes me suspect he was brought in to work at the Laver & Cowin foundry at this early date.

By 1870, Johnson was a 39-year-old master machinist whose real estate was worth $3,000, and personal property $500. His wife Sarah was 36; they had six children, all born in New Jersey, except the eldest, Sarah F. Johnson age 17 (born in New York State about 1853). The next eldest child, William M. Johnson was 12, born in New Jersey about 1858.26 In the census, the next family listed was Henry Gallagher, age 36, foreman in a foundry—no doubt another employee of William Cowin’s.27

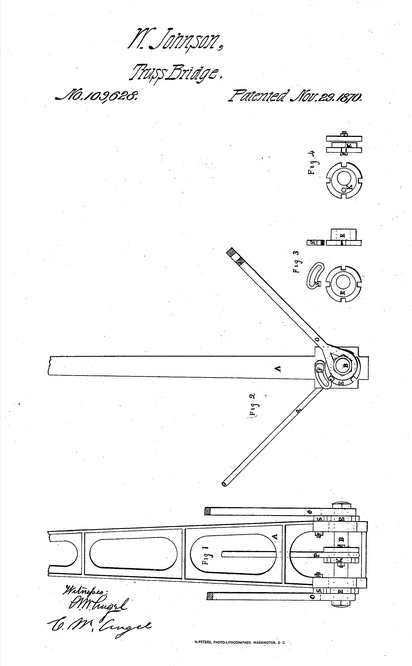

It is clear that by 1870, Johnson had developed some expertise in the construction of iron truss bridges. He filed a patent for “Improvement in Truss Bridges” on November 29, 1870.28 It described the use of “eccentrics” to tighten up the diagonal posts and to replace unreliable screw-nuts. Johnson’s patent appears to have been in use at least a year before it was granted. On March 31, 1869, William Cowin sent a bill to Joseph Smith & Co. for Iron Bridges, coal and freight cars, mill irons, machinist’s tools, and Johnson’s Patent Hangers. 29

The Bridges of Lambertville Iron Works

By the late 1860s, bridge projects had become an important part of William Cowin’s business. In 1868, the Lambertville Iron Works built a bridge spanning the Musconetcong River at New Hampton. In 1870, the company built a bridge at Glen Gardner, and most importantly, the lovely bridge over the South Branch at Clinton. This bridge must have established William Cowin as the pre-eminent builder of iron truss bridges in Hunterdon County.30

All three bridges were designed with cast iron for compression and wrought iron for tension, and are still standing. They are “composite cast and wrought iron Pratt pony trusses based on the patents of Francis C. Lowthorp, a well-known engineer of Trenton, NJ.”31

In June 1870, the freeholders advertised for bids on the construction of a bridge at Frenchtown, which was to be similar to “the one now in public use at Lambertville, near the gas works.” I do not know which bridge this was, but it seems likely this was another of the bridges built by Lambertville Iron Works. It was to be of wrought iron, with a span of 45 feet, and feature a sidewalk on one side made of pine planks.32 The freeholders expected the bridge to be open by September 20, 1870.

That year, according to the Industrial Schedule of the federal census, the Lambertville Iron Works employed 80 people, which made it the largest employer in Lambertville.33

On August 22, 1873, a contract was awarded to William Cowin of Lambertville Iron Works to build “a new iron bridge” at Milford. The notice in the Hunterdon Republican stated: “This firm has a good reputation, for reasonable prices and excellence of workmanship.”34

One of Cowin’s side businesses was the Amwell Mills Company, which was chartered on April 6, 1866, with William Cowin as president. The company produced cotton thread, but unlike the Iron Works, it barely survived the depression of the 1870s.35

William Cowin Departs

In 1870, Cowin was elected a director of the Lambertville Water Works,36 just another feather in his cap. By 1870, William Cowin was a very wealthy man. The census for that year, dated July 20th, showed Cowin as a foundryman, age 45, born in England, and having real estate worth $56,000 and personal property worth $60,500. His wife Caroline, known at that time as ‘Carrie,’ was 29. They had two children, Lucy age 5 and Walter age 3. Also living with them were two servants, Anna Reynolds 23 (born in NJ) and Bridget Costelyou 21 (born in Ireland).37

Being this rich made one vulnerable, as these two items in the Hunterdon Republican of 1872 demonstrate:

March 28, Stolen property recovered, a few weeks since. The valuable India shawl, which among other articles, was stolen from the house of William Cowin, of Lambertville, was recovered at a pawn-broker’s shop in Philadelphia, PA, where it had been pawned for a small sum.

May 16, Attempted robbery. On May 9, 1872, an attempt to rob the house of William Cowin, in Lambertville, was thwarted by an alarm which Mr. Cowin had put in his house since the robbery in February last.

In 1873, William Cowin took his family to England, perhaps to visit his birthplace and the relatives who had remained behind, but also in hopes of recovering from an unknown illness. His passport provides some information about him. He applied for his passport on October 2, 1873, with plans to travel to Great Britain with wife Caroline age 32, children Lucy 8 and Walter 6. Cowin was 47 years old, 5 feet 7 inches tall, medium forehead, blue eyes, straight nose, large mouth, medium chin, gray hair, fair complexion, and a long face. He was born in England on March 19, 1825, and was naturalized by the Hunterdon Court of Common Pleas, but no date was given for that.38

As things turned out, Cowin’s trip to England did nothing to improve his failing health. He died on November 10, 1874 at Lambertville, at the age of 49, and was buried at Mt. Hope Cemetery.39 The following obituary for him appeared in the Hunterdon Republican, on November 19, 1784:

Mr. William Cowin, proprietor of the “Lambertville Iron Works,” and one of the most prominent citizens of the place, died at his residence in that city on Tuesday of last week. Mr. Cowin settled in Lambertville in 1849, and shortly after established the iron works which have contributed so much to the business and prosperity of the place. About three years ago his health commenced failing, and all attempts at restoration, by travel and otherwise, have proved unavailing. The Beacon in noting his death, says:

“Few men have been held in high esteem in any community. Although outspoken and decided in the expression of his opinions, and never tolerant of wrong, so far as we know, he died without an enemy. A generous, true and warm-hearted friend, he experienced warm friendship in return, and without the least appearance of design, attached others to himself in bond of esteem and affection which death itself cannot sever.

“He was one of the most active and public-spirited of our citizens, ready at all times to promote the prosperity of our city. He served in the several offices of Mayor, Treasurer and Superintendent of Public Schools in such a manner as seemed the approbation of all good men. This community—any community—can ill afford to lose such a man. The Church, whose financial and benevolent interests as Trustee and Treasurer he so much promoted, can ill afford it.”

Such a fulsome obituary was not often seen in papers of that time. William Cowin died too soon. He was not among the Lambertville businessmen who had their portraits included in Snell’s History of Hunterdon County. Had he survived about five more years I have no doubt he would have appeared there. Fortunately, his obituary helps to fill that void.

Much to my surprise, I found that there is no will recorded for William Cowin in the Hunterdon County Surrogate’s Court, even though he was probably one of the richest men in Lambertville. His wife Caroline survived him by many years. A deed of hers dated December 22, 1905 increases the mystery. In that deed, Mrs. Cowin, widow of William Cowin, conveyed to George W. Prall for $8,500 a lot of ¾ of an acre, bordering North Union Street, Delaware Ave. and Clinton Street.40 She was identified as the sole legatee of her husband, and in the recital, the deed stated that Cowin had written his last will and testament which had been proved (recorded) “before the ordinary of the State of New Jersey November 24th 1874,” in which he devised all his real estate to his widow. When Mrs. Cowin acknowledged the deed, she did it before S. D. Oliphant, Master of Chancery, in Mercer County. Mr. Oliphant was the brother of Dr. Nelson Oliphant, husband of Caroline’s daughter Lucy, with whom she had gone to live in Trenton some time before the 1900 census.

I would love to see Wm. Cowin’s will and inventory, which may be on file with the State Archives. It would be of great interest to those of us interested in the Lambertville Iron Works. In part two, I will discuss the magnificent bridge that this company built.

Footnotes:

- June 30, 1897, Hunterdon Republican: The Cost of a Bridge. Sealed proposals for the steel bridge to be built over the Lackatong Creek at Strimple’s mill, west of Sergeantsville, were opened by a Committee of Freeholders last Saturday. Ten iron companies bid and the lowest was $850 by the Canton, Ohio, Wrought Iron Co. The mason work went to Mr. J. C. Wyckoff, of Annandale at $4.10 per cubic yard and the lumber contract was jointly awarded to Joseph Williamson and William Hartpence, each bidding $3.40 per hundred feet. The amount of lumber necessary is 3,232 ft., costing $109.89. ↩

- The painting hangs in my office. You can also find some good pictures at the Historic Bridges website. ↩

- One item that confused me was by Egbert T. Bush in “Story of Green Sergeants Covered Bridge and Its Builders,” June 30, 1935, in which he stated that Charles Ogden Holcombe built the bridge “spanning the Lackatong Creek at Hoffman’s, near the Delaware River” in 1870, but this cannot be the bridge being discussed here. He may have been referring to a bridge, crossing a tributary of the Lockatong, closer to Rosemont, where John Huffman lived. Bill Hartman found a reference to such a bridge in the Hunterdon Republican, but its exact location is uncertain. ↩

- His birthdate comes from his passport in 1873. ↩

- D’Autrechy, More Records of Old Hunterdon County, vol. 1, p. 135, citing Record Group 276, Hunterdon Co. Archives. Mrs. D’Autrechy did not find a record of naturalization for John Laver. ↩

- Lambertville census, Aug. 28, family #204-229. ↩

- These occupations still exist today. To learn more about the process, see this article from the National Center for Preservation of Technology and Training. ↩

- The year 1819 was stated in the advertisement of 1857, below. But Laver could not have been involved as he was only 12 years old at the time. Presumably he bought an existing foundry, but there is no deed recorded for such a purchase. ↩

- from Deed 116-537. Canal Street no longer exists. ↩

- Deeds 104-490, 114-310 and 118-318. ↩

- Deed 116-540. ↩

- Historic Preservation Master Plan Element, Lambertville City Planning Board, adopted September 5, 2001, p. 7. ↩

- Deed 119-629. ↩

- Hunterdon Gazette, March 16, 1859. ↩

- Also buried in the Mount Hope Cemetery were Robert Laver (1840-1919) and Emily Laver (1841-1916). Emily may have been the wife of Robert Laver, although there are no marriage records for Lavers in Deats’ Hunterdon Marriages. One would expect Robert Laver to be living with his parents in the 1850 census, being only 8 years old then, but I have not been able to locate him. There was a Robert Leaver, born in England 1842, immigrated in 1850, and living with his daughter in Trenton in 1910, but the 1850 census showed no children living with John and Hannah Laver. ↩

- Hunterdon County Surrogate’s Court, Wills Bk 10 p. 199. In 1862, William Cowin was named guardian of Emily Laver Makin, “late a minor.” This was repeated in January 1863. I have not examined the guardianship papers. ↩

- Wills vol. 10 p. 199. ↩

- Hunterdon County Surrogate’s Court, Inventory vol. 12 pp. 218-220. ↩

- Hunterdon Gazette, March 16, 1859. ↩

- That birth date is derived from the age given at the time of his death. However, if he was also the same as the Charles Cowin who was 11 years old and living with William Cowin (Sr.) in 1850, then there is a mistake somewhere. His gravestone seems to read 1838 rather than 1832. ↩

- Hunterdon Republican, Sept. 21, 1859, as abstracted by William Hartman. ↩

- U.S. Census for Lambertville, family #319-331. ↩

- This information can be found in “The Hunterdon Republican.” ↩

- NJ State Business Directory for 1866, Talbot and Blood, publishers and compilers, New York: Printed by C. A. Alvord, 15 Vandewater St., 1866. p. 150, Listed under Iron Founders, Forges &c., “Lambertville Iron Works, William Cowin (see card)” Listed under Iron Works, p. 151. A book titled In The Beacon Light, Lambertville NJ 1860 to 1900 claims that the company was founded in 1873, but I do not know what that is based on. ↩

- Deed 116-537. ↩

- U. S. Federal Census, Lambertville, family #555. ↩

- It appears that William Johnson built a house at 111 North Union Street in 1864, according to “The City of Lambertville Celebrates 150 Years of Its History,” published by Friends of the Sesquicentennial Committee in 1999, unpaginated. The notice states that Johnson sold this house in 1867 to P. C. Hoff, who can be seen on the Beers Map just south of William Cowin’s house. ↩

- Patent No. 109,628. ↩

- Lambertville Historical Society, box 54, #54-3632. ↩

- See The Bridges of New Jersey; Portraits of Garden State Crossings by Steven M. Richman, Rutgers Univ. Press, 2005, p. 61-63 . Richman states that the 1868 bridge was built by Wm. & Charles Cowin, but it is my understanding that Charles Cowin had died in 1859. ↩

- from Landmark American Bridges by Eric DeLony, p. 59. DeLony wrote that the Clinton bridge made use of “a tension adjuster patented by WilliamJohnson (my emphasis) in 1870.”[31. This had to be the patent described above; there is no other patent for William Johnson in 1870, but DeLoy’s description does not seem to match the drawing that accompanied the patent application. He wrote: “The drawing shows the intricate details of the castings for the vertical posts, the octagonal upper chord member and the railing that attests to the skill of the pattern maker as much as the engineer.” ↩

- Notice from the Hunterdon Republican, June 16, 1870. ↩

- I have not seen the U.S. Federal Census, Industrial Schedule for 1870 myself. This information came from the Plunckett application to the National Register. I did find the NJ Industrial Schedule for 1870 on microfilm at the Hunterdon Co. Library. It’s almost illegible, but it does list William Cowin producing “Carr Wheels” with capital invested of $25,000. It states he had 30 machines, but I wonder if that might have been an error, since there was no figure given for employees, which is the next column. I know there is a lot more information on that form, but I just can’t read it. I am surprised there was no mention of the Lambertville Iron Works. ↩

- Hunterdon Republican, August 28 1873. ↩

- Snell, p. 284. ↩

- Hunterdon Republican, Aug. 4, 1870. ↩

- U.S. Federal Census for Lambertville, family #638-685. ↩

- Passport No. 35348. Record dated Oct. 3, 1873; image from Ancestry.com. ↩

- Oddly enough, there is no listing in Find-a-Grave for his parents, William and Sarah Cowin in the cemetery; perhaps their stones are missing. ↩

- Deed 276-697. ↩

Sharon Moore Colquhoun

August 22, 2014 @ 7:58 pm

Marfy, I laughed at your comment about the two Johnson families not being related. My friend at the State Archives is thrilled when I look up ancestors such as Readings or Updikes or Holcombes. “Wow, someone with money who might have a will!” We can glean lots of info from the wills! Thanks for the article.

Sharon Moore Colquhoun

August 22, 2014 @ 8:00 pm

And Phyllis D’Autrechy would be loving my research from the Archives! Phyllis was my 6th grade teacher.

Ron Warrick

August 22, 2014 @ 9:17 pm

Great article, Marfy. It’s curious that two children in the Cowin household were born in America in 1839 and 1844 if the family only emigrated to America in 1849, though.

Marfy Goodspeed

August 31, 2014 @ 11:40 am

Nice catch, Ron. Yes, that is curious.

Ron Warrick

August 22, 2014 @ 9:23 pm

“Even an engineer can tell that this bridge is something special.”

Speaking for us engineers, just what is that supposed to mean?! :-)

Marfy Goodspeed

August 31, 2014 @ 11:42 am

Tongue in cheek, Ron. I’m sure you know how engineers see safety and utility issues before aesthetics ever cross their minds. Or even consider that widening a road or bridge actually increases traffic speeds. Don’t get me started. But hey–some of my best friends are engineers, so there you go!

Carolyn

August 23, 2014 @ 12:08 pm

A timely and terrific article on the history of the creators of our lovely

Raven Rock-Rosement Bridge. I was delighted to hear of the connection of Caroline Cowin with the notable Ashbel Welch. So many people – so many stories.

Thank you! Can’t wait to read Part Two.

Art S.

June 3, 2019 @ 6:05 pm

Here is a photo of the bridge you referenced in Milford: http://bridgehunter.com/nj/hunterdon/bh83169/ I added the build date based on your work.

Isolation Photo Project, Day 103 by Khürt Williams on Island in the Net

July 4, 2020 @ 10:08 am

[…] The Lockatong Bridge on Raven Rock Road, part one […]