Most people who decide to research their properties head straight to the Search Room in the County Clerk’s Office to find the earliest deed they can. I understand the impulse—that’s exactly what I did over 30 years ago. But experience has taught me there is a better way to get started. I recently gave a talk on this subject for the Hunterdon County 300th Anniversary speakers’ series. It gave me a chance to boil down my approach to a few simple rules. Here they are:

Step One. Visit people and get their stories.

Step Two. Study your architecture and your location.

Step Three. Establish your Chain of Title.

Step Three & a Half. Find the “Missing Links.”

Step Four. Flesh Out the Story.

Step Five. Put it All Together.

That’s it. You will probably find yourself working on more than one step at a time. But first you need to know what the steps are. So, let’s break it down.

Step One: The People and Their Stories.

Seek out the old-timers, the people who are now in their 70s or 80s or even 90s who might have spent their childhoods in your house or in your neighborhoods. Their recollections are priceless, and once those people go—which they will all too soon—their memories will be lost. They are a sadly neglected and yet very important resource. So start with them. You don’t know how much time they have left, so don’t put it off, and be sure to bring your smart phone or tape recorder (rather obsolete now) and record the interview.

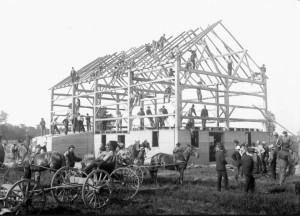

Chances are you will be greatly entertained by the visit, and, if you’re lucky, they might have old photographs they can share with you.

Step Two. Architecture and Location

Photographs

An early photograph of your house is a priceless gift. You will quickly see how different houses looked in the 19th or early 20th century from how they look now—even if previous owners made no significant changes to the structure. This is why it is sometimes hard to estimate the age of a house by its exterior. An old photograph could give you some very important clues.

Architecture

Try to educate yourself on architectural styles, and the components of older houses. Learn the difference between post and beam and balloon-frame construction. Look for original materials like floor-boards and nails, especially nails. Study the woodwork if it’s original to the house.

One important thing to keep in mind is that we live in what might be considered a backwater. New architectural styles were first used in more developed areas, closer to New York and Philadelphia, while Hunterdon carpenters and builders preferred to stick to the older styles, long after they went out of fashion.

There are many good books on the subject. My favorites are by Eric Sloane, like Our Vanishing Landscape and A Reverence for Wood. These are not exhaustive professional studies of colonial architecture, but they are fun to read, and Sloane’s drawings are wonderful.

When it gets right down to it, if there is any question about the age of your house there are two ways to get good answers, and they both cost money. First—get a bone fide architectural historian to visit your house and give you a report, verbal or written. You will learn a lot about your house, but will probably not get an exact date of its construction. For that you need to have a dendrochronology test done. This involves boring into a beam, right through its core, and studying the sample to count the rings in the wood. It is surprisingly accurate, but it is also expensive and takes a long time to do. However, if you think you have a real historical gem of a house, I strongly recommend that you do it. There is just one caution–the date of the beam will be the date that the tree was harvested. There are many cases in which a house was built using materials from an earlier house. Caution is advised, as always.

With a sense of the time-frame of your house, your work in the Search Room will be more accurate and focused. You’ll need this because you are not going to find a record on file of when your house was constructed. Certificates of Occupancy, builder’s permits, approved site plans and all the other bureaucratic records that are required today did not exist until the mid 20th century. So we have to find another way.

Maps

Along with a sense of your house’s architecture, you need the information that old maps can provide, along with a good map of your property’s location. These are the most important maps to find:

1) Your Tax Map

Get the map for your block and lot and for surrounding blocks. Visit the County Clerk’s office to get the size that is printed on 11 by 17” paper; it is the most useful, and since they have a complete collection for the entire county, you can easily get maps for surrounding areas. (Getting them copied onto 11×17 paper will take some assistance from the clerks.)

One caveat—these maps are current, which means they show all the subdivisions. But you are more interested in what your area looked like before all the subdividing was done. Ask your municipal clerk if there are any older tax maps on file. If not, you can entertain yourselves by whiting out subdivision lines. Just be careful not to white out older lot lines.

2) Aerial Photographs

Both wide focus and close in.

These are invaluable for displaying hedgerows, which are often old lot lines that may have disappeared from the tax map. They can also give you hints of old roads. Fortunately, you can get these easily with Google Maps. Be sure to print out copies.

Not only can you get your aerial photo from Google Earth, you can go to a new website called History Mapping (www.historymapping.org) and find tax maps overlaid with aerials as well as the major historical maps for Hunterdon County. Definitely check this out.

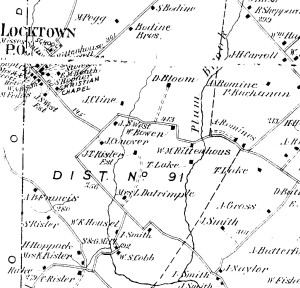

3) The Beers Atlas of 1873

This is one of three major 19th century maps to show property owners or residents in Hunterdon County. This one comes in several formats, but the most useful is in book form, with a page for each municipality. You can find the Atlas at the Historical Society or the County Library. Get a good photocopy or take a photograph. At this time, the Historical Society has only two copies for sale. If you decide you want to purchase one and they’ve sold out, be sure to let the executive director Linda Hahola know that you’d like the trustees to order new copies for sale, and be sure to give her your contact information. Alternatively, you can find the Atlas online through the Hunterdon County Library’s website (high resolution tif images).

4) Philadelphia and Environs, 1860

Unfortunately, as far as I know, this map has not been reproduced for purchase. There are several original copies to be found; one is at the County Library and another at the Historical Society. Others are owned by private collectors. Because they are originals, they have darkened with age and can be hard to read. But they’re still worth seeking out. You can try to capture a photo—good lighting is essential.

5) The Cornell Map of 1851

This is the first of the historic maps that indicates property owners by name. There are earlier maps of Hunterdon County, but this is the first with farmhouses located. You can get a copy of this map from the Hunterdon County Historical Society. You can also find it online from the “American Memory” page of the Library of Congress.

6) Sanborn Insurance Maps

The Cornell, Philadelphia and Beers maps don’t help much if your house is in a town like Clinton. Especially with the 1851 map, the houses are too close together to be depicted. The Sanborn Insurance Maps come to the rescue, at least for the late 19th century. They show small town lot lines and structures in surprising detail, along with names of owners. They were published at different times—Clinton 1886-1939; Flemington 1885-1921; Lambertville 1885-1923, etc. They are available at the County Historical Society. Like the Beers Atlas, you can find images of the Sanborn Maps online, made available by the Princeton Library.1

7) And finally, the Hammond Maps

For the earliest landowners (but not necessarily residents), get a copy of the Hammond map for your area. These maps were drawn by D. Stanton Hammond in 1963, based on the earliest surveys and land purchases on file at the State Archives.2 The maps are invaluable for getting back to the first owner of your property. They don’t have the answers for everyone, especially for north Hunterdon, where land transactions were far less well-documented. But anyone researching their house must take a look at them. I frequently make use of them on my website.3

The maps are available at the County Library and the Historical Society. You can purchase your own set of maps from the Genealogical Society of N.J.

Step Three: The Chain of Title

Now you know something about your property’s 20th century owners, you know who was in residence in 1851, 1860 and 1873, and you have a good idea of your property’s lot lines and configuration. Finally, you’re ready for the search room.

Think of a chain with many links. Each link is a transaction in which the ownership of your property changed. You hold the last link. Your challenge is to find all the links all the way back to the first one in the chain.

To do this, you need to learn how to read a deed, how to recognize what is essential information versus boilerplate. But also, you need to know what boilerplate can be ignored and what is important. If you are really interested, study real estate law—it can be an eye opener. Some of the ancient phrases found in deeds are down-right poetic, like “to have and to hold. . . ” Makes you realize that for hundreds of years, marriage ceremonies were more about property than romance. In fact, land ownership law still has vestiges of the feudal system from which it emerged.

You will soon discover that for deeds recorded before around 1920, land was measured not in feet and inches but in chains and links. Time to learn about a Gunter’s Chain, which was 66 feet long and had 100 links, each link being 7.92 inches. This was the gold-standard for measuring land ever since 1620 when it was introduced by Edmund Gunter in England.4

Abstract Your Deeds

Get a copy of Phyllis D’Autrechy’s book House Plans for good advice on what is important in a deed and what you can ignore. As it turns out, not that much. As Phyllis wrote: “Don’t be in a hurry to dash to the next deed. A hurried job will make a . . poor research project. There aren’t any short cuts.” This is excellent advice—and very difficult advice to take. You’ll probably learn the hard way, and have to go back and start over. I’ve done it myself. It would take an entire post to describe how to read a deed. Instead, I refer to House Plans for a good introductory course.5

Plot Your Deeds

You will never be completely certain that you have the right deeds in your chain of title unless you plot out the deeds and locate the property on the tax map. If you don’t plot your deeds you could end up on a wild goose chase, researching a completely different property.

To plot a deed, that is, to draw out the lines described in the metes and bounds, you will need a protractor, a sharp pencil, some graph paper and a nice metal ruler. You will also need a scale to translate the chains and links into a size suitable for 8-1/2” by 11” paper. I have found that a very useful scale for matching chains and links to the usual tax map on 11” by 17” paper is 0.2 cm = one chain, give or take. There are software programs that do this work for you. Last time I checked, the good ones were pretty expensive, and the affordable ones were pretty inaccurate. That may have changed. If you find a good one, it will make your work a lot easier.

Once you’ve become familiar with the way deeds are written, recorded and kept in the Search Room, you can research earlier deeds by visiting the website Family Search where they list microfilmed copies of the deed indexes up through 1955 and the deed books up through book 300. Obviously a great time saver, but remember, you still must visit the Search Room for the other land records they have there.

Step 3-1/2: Find the Missing Links

This step is really a part of Step Three. One of the essential parts of a deed is the recital. The recital explains who the seller bought the property from and takes you back to the previous deed. Not all deeds have recitals. When the recital is missing, you have to scramble to get back to the previous owner.

Here’s one example: a sale in 1866 by Peter Rockafellow to William Bodine, and no recital. So who did Rockafellow get it from? First thing to do is look for Peter Rockafellow in the Grantee Index to see what properties he purchased before 1866. If it turns out he has many deeds, you will have a lot of work on your hands checking each one out. But it must be done.

A tip: Watch out for those dates in the index books. They are the dates when the deeds were recorded, not the actual deed dates. Sometimes people did not record their deeds until the owner had died and the estate needed to be settled.

So, let’s say there are a lot of deeds for Peter Rockafellow. What to do? Go back to your maps. The 1860 map shows “P. Rockafellow” at the location of our property. Good. But the 1851 map shows “A. Holcombe” there. Even better. Now you can look for a deed in which an A. Holcombe sold land to Peter Rockafellow. There could be an intervening owner, but chances are this approach will get you to the next deed in your chain of title. It just shows how invaluable those old maps are.

Do not forget to check on mortgages while you’re in the Search Room. For some 18th century owners, the deed never got recorded but the mortgage did.

Sheriffs’ Sales and Estates

Phyllis D’Autrechy’s book House Plans is an excellent guide to dealing with these sticky situations. One of her techniques covers cases when the owner was taken to court for unpaid debts and had his property confiscated. If it’s a Sheriff’s sale, chances are the previous owner was the defendant who is usually identified in such deeds. With the name of the defendant, you can head back to the index books.

Sometimes the lack of a recital is explained by there being a transfer of ownership in the family after an owner has died, in which case, the next owner will probably not show up in the deed index. The solution is to research the genealogy of the last known owner (to be discussed in a subsequent post) or to examine the deeds of bordering owners for clues to your owner.

Keep Track of Your Research

Researching a house can take a long time, and you will probably find your project interrupted by such trivial matters as work, vacations, family emergencies. It is easy to lose track of what you’ve done, especially if you have to take a break of several months or more.

Keep a Research Log in a notebook

And take your notebook with you every time you venture forth. For every research excursion, make note of the following:

- Place and date of visit

- Name of person you are researching

- Document searched, with detailed information that you can use in citations

- Results, whether positive or negative

- Indicate whether you made a photocopy or took a photograph or just made notes

Make copies of every relevant document you find—do not trust your notes. And if you found information in a book and made copies from it, be sure to copy both the title page and the copyright page.

Make a Chronological Chain of Title

This chronology will be your basic structure for the history of your house. It will be your guide from here on. For each link in your chain, note down the bare essentials, like date, grantor, grantee, acreage, cost and, of course, the source.

When you get new information pertaining to the owners of your house, slot it into your chronology, and you will find that you are creating the basis for an actual house history.

The bare facts can show you some interesting things. For instance, it was a common practice for large farms of 300 acres or more to get divided into smaller parcels as families tried to pass on the farm to their children. By knowing the amount paid and the amount of acreage, you can calculate the cost per acre. Then look to see if there were big changes between deeds in the value of your property. This can be an important clue as to when your house was built.

This is enough for now. Steps Four and Five will appear in the next post.

Footnotes:

- Thanks to Michael Dox for providing links to the Beers Atlas, the Cornell Map and the Sanborn Maps. ↩

- Dean Stanton Hammond died in 1992. I had long thought he was part of the Hammond map-making family, but now I am not so sure. He was for many years a principal of a public school in Paterson, and died there. But he must have spent some time in Hunterdon to become so interested in its early landowners. ↩

- You can see the Hammond Maps overlain on aerial photos by going to www.historymapping.org. ↩

- One good place to learn more about this is Measuring the Land by Andro Linklater (Penguin, 2003), especially Ch. 1, Invention of Landed Property. ↩

- Copies of the D’Autrechy book are available at the Hunterdon County Cultural & Heritage Commission. If they are sold out, ask them to republish, and in the meantime, visit the County Library to see a copy. Phyllis D’Autrechy served as County Archivist from the 1970s through the 1990s. During the course of her tenure she made huge amounts of information available to researchers, first by a complete reorganization of the county records, and by her three books, which are listed in the Basic Resources section of Basic Sources page of this website. ↩

Pamelyn Bush

March 30, 2014 @ 1:18 pm

Hi Marfy, I can add a correction to the footnote about Dr. Hammond who died Jan. 22, 1982. His name was Daniel Stanton Hammond III, but went by the name of Stanton to his friends. There is an “appreciation” of him in the Genealogical Magazine of NJ, Vol. 57, No. 3, September 1982, pp. 97-98 by Kenn Stryker-Rodda. He was born Sept. 22, 1887 in Brooklyn, the son of Daniel Stanton Hammond II and Helyne Myra Scott. He moved to NJ at the age of 5, graduating from Ridgewood H.S. and Trenton State Normal School. Along with many other towns in NJ where he taught, he was principal of a grammar school in Flemington which is where he began his interest in Hunterdon deeds. He and Deats were both active early members of GSNJ and would have had in common, their love for genealogy. He earned a J.D. degree from NYU in 1923 which is how he earned the title Dr. Hammond. His greatest contribution to GSNJ of which he was a trustee, was the making of genealogical maps, not only Hunterdon, but Bergen, Gloucester, Cumberland and Burlington counties as well. The creator of the Hammond Map company was Caleb Stillson Hammond, also born in NYC, but if they were related, it was remotely because they have different fathers and grandfathers. I once found myself seated next to Dr. Hammond at a genealogical seminar in 1978 or 1979, and asked him if he was connected to the founder of the Hammond Map Corp in Maplewood. He replied but for the life of me, I can’t remember what he said.

Pam Bush

Marfy Goodspeed

March 30, 2014 @ 5:03 pm

Pamelyn, This is wonderful information. I have always wondered about Hammond’s life and antecedents. Thank you so much for the biography.

Sharon Sweazey

March 31, 2014 @ 12:07 pm

Dear Marfy,

I have been so interested in the history of our home(207 March Blvd. Phillipsburg NJ). A lot harder than I thought- No info at all at our Municipal/ Tax office,no info @ P’burg library, spent countless hours online. I only know that my home is a Sears kit from 1935ish, spent 3 hrs. researching Sears Home designs, not a big seller in NJ, but photos of different Sears homes found in Southern states, none of my design found. I know the name of the couple(deceased prior to purchase) who lived in our home. The couple worked @ Bethlehem Steel. Any advice? Thank you, Sharon (908)859-8511

Marfy Goodspeed

March 31, 2014 @ 2:02 pm

Sharon, I regret to say I have no experience researching the type of house you have. I am surprised you haven’t been able to find a building permit or certificate of occupancy, but perhaps regulations for that were not in effect in the 1930s. I believe that people have been lately doing a lot to get information about Sears homes, so perhaps you could get some help from them. I just did a Google search using the terms “1930s sears house” and got a lot of links to check out. Sorry I can’t help you more. Perhaps some of my readers might have suggestions.

Lara

January 2, 2015 @ 6:43 am

Hi, Sharon! I came across your post in a Google search. NJ had loads of Sears houses since there was a plant in Newark. Bethlehem Steel was also known for constructing Sears houses for its workers.

If you’d like to send me photos of your house, I can help you identify it. The reason you cannot find the model might be because it may not be from Sears at all–the vast majority of people who are told they have a Sears house don’t have one.

Lara

Sears Homes of Chicagoland

sears-homes.com

Marfy This Month: April 2014 | Hunterdon County Historical Society

April 1, 2014 @ 10:39 am

[…] “March 29 I gave a talk on doing house histories. It was part of the Hunterdon County 300th Anniversary speakers series. I had a lot to say on this subject, so it seems like a good idea to publish a version of that talk on the website. This should be considered an introductory lesson on how to research your property. But it’s still long enough to be published in two parts. I hope this will help get you started on your own house history.” The Secrets to a Great House History. […]

Cynthia Bruning

June 3, 2014 @ 5:39 pm

Hello Marfy, I have been trying to research a property on Lambertville Headquarters Road. I did exactly what you said – ran to the records room at the county. I was able to track the deeds back to the early 1800’s. I did get stumped when the grantee purchased 2 properties and could not determine which one was the correct property. I was told the house was built in 1798 and was hoping to find the first owners. The house sits far back from the road and the owner had heard something about there being a road which may have been an extension of Zentek Road at some time. A few of the deeds refer to the Whitehall marker. I was hoping to find some historical information about the area during its initial settlement. Any suggestions would be helpful and appreciated. Thanks Cindy

Marfy Goodspeed

June 25, 2014 @ 2:31 am

In order to figure out what the two properties are, you need to plot out the metes & bounds and compare them to the tax map or to an aerial photo to see where they are located. This problem turns up fairly often–several lots sold in one deed. You may end up following more than one trail back through the chain of title.