Many years ago, Bob Dilts wrote an article entitled “Sergeantsville’s a Nicer Name.”1 While describing George Fisher’s harness shop (pictured below), on the southeast corner of the main intersection, Dilts wrote a paragraph that really caught my attention:

“It is also thought that the upper floor was used as a lodge room by the Wicheoechee [sic] Tribe of Red Men before that organization moved to Flemington. A story, related by Frank Burd, is that a boy climbed a nearby tree to look in on the Red Men’s initiation one night and came down wondering what grown men were doing running around the room with feathers on their heads.”

I have long wondered what the “Wicheoechee Tribe of Red Men” was. The real “red men” had long since left Hunterdon County. These were obviously adult white men pretending to be Indians. But why?

The Name ‘Wickcheoche’

Before I go further, an explanation of the name “Wicheoechee” is in order. I’m sure many readers are familiar with the name Wickecheoke, which designates a Hunterdon County trout stream of great beauty running from Franklin and Kingwood Townships southwest through Delaware Township until it empties into the Delaware River at Prallsville. The name is unusual, but its source is the same as most of the creeks and rivers in New Jersey—from the Native Americans who first lived here. There are theories about what it means, but I discount those because the spelling we use today is a corruption of what the Indians were saying. The creek shows up in early 18th century proprietary records spelled as Quachechecake, among many other variants—all of which start with a Q. Even after the Q was switched to a W, there was no agreement on how to spell it. The Tribe of Red Men spelled the name “Wickcheoche,” and that is the spelling that is still preferred by them.

Addendum, 12/31/15: I discovered in a deed of 1812 (Book 19 p. 248) another spelling for the creek: “Witchitchechoke.” Try pronouncing that!

The Improved Order of Red Men

And as for the “Tribe of Red Men,” it turns out the men with “feathers on their heads” were members of a fraternal organization known as the I. O. R. M., or Improved Order of Red Men. I have learned, to my surprise, that the I. O. R. M. is still in existence. According to the organization’s website, its roots go back to secret societies such as The Sons of Liberty (responsible for the famous Boston Tea Party, dressed as they were, as Indians) and The Sons of St. Tammany.

Most interesting to me is that “St. Tamany” was actually Tamanend, a Lenape sachem who negotiated with William Penn in 1683 (as depicted in the painting by Benjamin West, above), and is most famous for stating that the Lenape and the English colonists would “live in peace as long as the waters run in the rivers and creeks and as long as the stars and moon endure.” From this he gained a reputation in Philadelphia as a peace-maker (hence the “saint”), and in 1772 the first Tamany society was formed there. Soon there were Tamany societies throughout the colonies, which is odd considering that their members were preparing to go to war with Great Britain.

Most interesting to me is that “St. Tamany” was actually Tamanend, a Lenape sachem who negotiated with William Penn in 1683 (as depicted in the painting by Benjamin West, above), and is most famous for stating that the Lenape and the English colonists would “live in peace as long as the waters run in the rivers and creeks and as long as the stars and moon endure.” From this he gained a reputation in Philadelphia as a peace-maker (hence the “saint”), and in 1772 the first Tamany society was formed there. Soon there were Tamany societies throughout the colonies, which is odd considering that their members were preparing to go to war with Great Britain.

After the Revolution had ended, these various societies continued to grow. Their members were often veterans seeking to maintain the bonds that had been created during the war. This was the American urge to associate which De Tocqueville found so amazing during his trip to America in 1831. The Order claims that it is the first fraternal organization of American origin, which is true if one accepts that its roots go back to the Sons of Liberty.

It took another war, the War of 1812, to bring all the separate groups together. In 1813, at Fort Mifflin near Philadelphia, a meeting was held in which a new organization was formed called “The Society of Red Men.” Later, in 1834, the named was modified to “The Improved Order of Red Men.” The local branches of this club were called tribes, hence The Wickcheoche Tribe of Red Men.

In 1847, the national organization reorganized itself at a meeting in Baltimore. The various “tribes” agreed to create “The Grand Council of the United States,” and later on Great Councils in the states were created. By the 1920s, membership had grown to a half million in 46 states. And this included the Wickcheoche Tribe of Red Men, No. 24, which organized in Sergeantsville in March 1871.2

The Wickcheoche Tribe

There were 29 original members, but the list of their names has been lost. However, the first officers (and probably the men most responsible for recruiting the first members) were: William A. Hoff, S. R. Bodine, Jonathan Kitchen, J. M. Cox, Lt. Warman, and William Wencel [sic].

William A. Hoff. It has been a challenge getting information about William A. Hoff. From what I can tell, he was the son of Rev. Jacob Hoff and Sarah Hoffman, who moved to Delaware Township from Tewksbury around 1860. He was born about 1837, and on May 22, 1860 married Mary A. Prall of Quakertown, daughter of Samuel Prall and Sarah Ann King. In the 1860 census, William and Mary were living with William’s parents in Delaware Township, William working as a farmer. I cannot say if William and Mary had children because I have been unable to find them in the subsequent census records. But William does appear in the list of those to be drafted from Delaware Township in 1864.

S. R. Bodine. This was Samuel Reading Bodine, born 1846 to William Bodine and Delilah Ann Rittenhouse. He married Sarah L. Larison, daughter of Benjamin and Hannah Larison, about 1872.3 They had two children, Mary Hannah, in 1874, and Lucy L. Bodine, in 1876. Samuel R. Bodine grew up on his grandfather Benjamin Bodine’s farm in Delaware Township, and continued to live there after he married. He was a farmer all his life, and died age 75 in 1920. His wife Sarah died the same year and both were buried in the Sandy Ridge Cemetery.

Jonathan Kitchen. He should not be confused (and I was for awhile) with Jonathan P. Kitchen, a shoemaker, born about 1816 to Charles and Sarah Kitchen, who married Catharine Agin in 1838, and died intestate in 1860 (his estate was administered by Ely Kitchen). The Jonathan Kitchen who belonged to the Wickcheoche Tribe of Red Men was a blacksmith, born 1820/21, but I have not identified his parents. He married Cornelia Groenendycke in 1844. In the 1850 census for Delaware Township he was a blacksmith with wife and three children (Nelson, William and Mary); in 1860, he was in Everittstown, with two new children, Catharine and Alwilda); in 1870 he was in Frenchtown and in 1880 in Franklin Township. He became a Justice of the Peace for Clinton Boro in 1888, and was nominated for Assembly by the Prohibition Party in 1890. He died in 1893 but I have not located his grave.

J. M. Cox was James Morgan Cox, son of Rev. Morgan R. Cox and Mary Bray Rittenhouse. He was born in 1841 and married Mary Jennie Rittenhouse, daughter of neighbors Wilson B. and Rachel Rittenhouse, in 1872. They had no children. James M. Cox lived on his parents’ farm on Rittenhouse Road, and continued to live there after their deaths. He was a poultry farmer in 1891, as attested by this item in the news:

James M. Cox of Delaware Tp., near Sandy Ridge, has 140 hens that laid 3,700 eggs from 1 Jan. 1891 up to 16 Mar. 1891. There were 1,088 in January, 1,000 in February and the rest in March. At 25 cents a dozen, he would realize $72 for the eggs.4

Like his father, James M. Cox was a devoted Baptist, and was very active in the Sabbath School (later called Sunday School) movement, and in the Sandy Ridge Baptist Church. His wife Jennie died in 1900 and he survived to 1922, dying at age 80. They were both buried in the Sandy Ridge cemetery.

Lt. Warman was William S. Warman, son of Jacob Warman and Sarah E. Bodine (making him a first cousin once removed to Samuel R. Bodine, above).5 He was born January 1828. His wife was named Catherine, but I have not found her parents. She was born in 1823, and they must have married about 1863, although I have not found a marriage record for them. Like most of the other original members of the Wickcheoche Tribe of Red Men, Warman was a Delaware Twp. farmer, but was identified as a married cooper, age 36, in 1863 when he registered for the draft. William and Catherine had two children, Jacob C. Warman, born 1865, and Theodore A. Warman, born 1868. William Warman died in 1908 and was buried in the Barber Cemetery. His wife moved to Sergeantsville and survived him until 1926 when she died and was buried next to him.

William Wencel was William Wenzel, born in Germany in 1834. He came to America in 1849 and was naturalized. In 1854, he married Hannah H. Bowne, daughter of John D. Bowne and Sarah Cronce, and they had three daughters. Although he was living in Delaware Township in 1870, he had moved to Raritan Township by 1900. Hannah Wenzel died in 1872, and was buried in the cemetery of the Presbyterian Church in Flemington. William married second Esther Butterfoss (born 1832) in 1874. They had a daughter Elizabeth, who married William C. Cook of Trenton in 1899. William Wenzel was a farmer all his life, but he dabbled in politics in the 1890s when he helped organize the Hunterdon County Taxpayers’ League. He ran as a Democrat for the Raritan Township Committee in 1898, but was defeated by Asa H. Fisher. William Wenzel was still involved with the Wickcheoche Tribe of Red Men in 1883 when the lodge elected its new officers. He died in 1915 at the home of his daughter Anna and son-in-law Joseph Alvater in Flemington. He was 81 years old, and was buried at Prospect Hill Cemetery next to wife Esther.

The Wickcheoche Tribe of Red Men first organized in Sergeantsville, but in 1880 they decided to move to Flemington, probably because more of their members were coming from that vicinity. The view that the young boy had at Fisher’s Harness Store must have taken place between 1871 and 1880, so he was probably born not long after the Civil War ended.

Why Red Men?

It is rather ironic that white Americans, who were responsible for creating so much devastation among Native American communities, would be paying tribute to their social organization and their freedom from contamination by corrupt European American civilization. Here’s some more irony—at the time that the Improved Order of Red Men was reorganizing and becoming more popular, President Jackson was doing his best to remove Cherokee and Creek Indians from their ancient homelands, and did so in a very brutal way.6 One wonders how Native Americans felt about being mimicked by these white men’s social organizations. It is complicated. One has to remember that attitudes in the 19th century were very different from today. In fact, in 1892 an actual American Indian became a member.

“The first Indian ever initiated into a lodge of Red Men in New Jersey was admitted into Red Jacket Lodge, of Lambertville, last week. He is James McAdams, a dry goods clerk and graduate of the Indian School at Carlisle, PA.”7

I have long been bemused and befuddled by the ceremonies and rituals of secret organizations for men only. (By the way, there is a parallel group for women called “The Degree of Pocahontas.”) David Lintz reminded me that “All fraternal groups had secret ceremonies. That is what set them apart from other membership organizations.” Secretiveness was justified, in part, by the need to preserve special rituals, like wearing Indian costumes and feathered headdresses, and, no doubt, dancing and chanting during initiation ceremonies.8

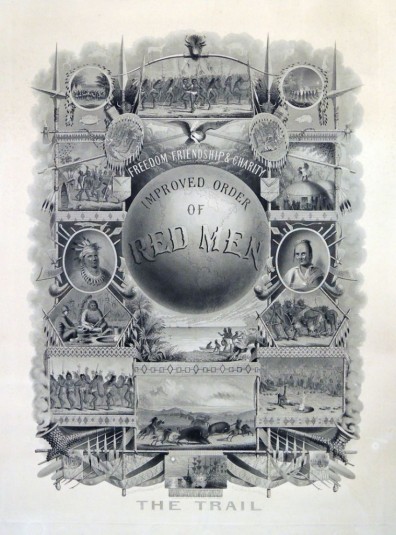

In 1888, a broadside entitled “The Trail. Freedom, Friendship & Charity. Improved Order of Red Men” was published, and the cover is so marvelous, I had to include it here.9

For some groups, the primary motivation for joining was the opportunity for social events. I was charmed to read Egbert T. Bush observe that the Delaware Vigilant Society, which was organized in the early 19th century to insure members against the loss of horses from theft, ended up being just an excuse to have a nice monthly dinner together. “The Red Men of Flemington” were probably similar. In May 1886,

“The Red Men, of Flemington, partook of a sumptuous collation at the dining parlors of John H. Stockton, Flemington’s popular caterer, on Friday evening. A number of visitors from various lodges were present.”10

Some Hunterdon Tribal Members

Some men couldn’t seem to get enough fraternal company. David Curtis is one such. He died at his home in Milford on December 10, 1887. His obituary in the Hunterdon Republican listed the organizations he was a member of: “Leni Lenape Lodge, No. 15, Odd Fellows and the Delaware Encampment, No. 11, of Patriarchs, of Lambertville, . . . the Masonic Lodge and of the Tribe of Red Men at Frenchtown.”

I sometimes wonder if men like Curtis were henpecked husbands looking for an excuse to get out of the house. There were better reasons for forming these clubs. It was partly that old American urge to associate. For some, it might have been the effect of war on surviving combatants, who had learned to rely on each other for their survival and continued to need those bonds of brotherhood after the wars ended.

David Lintz wrote that “secret societies were also called beneficial societies or friendly societies. . . . There were usually one or more of four reasons why a man would join a fraternal group – business, political, social, or beneficial (insurance). Those joining as beneficial members paid more in dues to cover their insurance costs. Many men belonged to more than one group to increase their standing in the community or their benefits coverage.” Which explains David Curtis.

Sometimes that insurance coverage was not made available. The Hunterdon Court considered the case of the Tuscarora Tribe, Independent Order of Red Men vs. Jacob S. Dean in 1887. “The action was for the recovery of certain benefits which Dean, having become sick, claimed he was entitled to under the constitution of the order. It was contended that he had not fulfilled all the requirements of the constitution and by-laws in his efforts to collect these benefits within the Order,” so the case was dismissed.11

Then there’s the case where donations were made instead of insurance payments:

“Some very liberal donations have been made recently to Frank Rooks, who lost his house by fire, on Mount Gilboa, a hill of about 150 feet, Southeast of Stockton in Delaware Tp. The Tuscarora Tribe of Red Men, donated $100.”12

The earliest mention of the Improved Order of Red Men in the Hunterdon Gazette was dated March 21, 1866, in which “A tribe of the order of Red Men is shortly to be instituted in Frenchtown, as soon as a suitable room can be procured for the purpose.”

Then in 1871, The Wickcheoche Tribe of Red Men was organized, but I did not find any mention of it in the newspaper abstracts. In fact, no mention of the society until December 16, 1880 in the Hunterdon Republican (although I probably missed mentions in the Democrat). It seems that for the most part, the organization did not publicize its meetings the way other organizations did, at least not until 1883, when notice of new officers was published.13

“New Officers. At a meeting held on 5 Jan. 1883. These are the new officers of Wickecheoke Tribe, No. 24, Independent Order of Red Men, of Flemington: S: Asa S. Dalrymple; S. S.: Henry Snyder; J. S.: Charles A. Higgins; C. of R.: John Parks and K. of W.: William Wenzel. They occupied their new room in the Deats’ Building, which they have very nicely fitted up and furnished.”14

Apparently readers knew what the positions of this organization were. It took me a little study to figure out that S meant “Sachem”; S. S. meant “Senior Sagamore”; J. S. meant Junior Sagamore”; C. of R. meant “Chief of Records” (secretary); and K. of W. meant “Keeper of Wampum” (treasurer). Another important position mentioned in the newspaper was P (Prophet), although I do not know what that entailed.

The Wickcheoche Tribe was not the only tribe in Hunterdon County. There was also one at Frenchtown (as noted above in the 1866 Gazette; their Dues Book for 1914-1922 can be found at the Historical Society). And there was the Beaver Tribe in 1884 of which Charles J. Waidman of Hampton was a member.15 And a Capoolon Lodge, presumably near Quakertown. There was also a tribe at High Bridge whose “paraphernalia” was destroyed in a huge fire that burned down the Rialto Hall Building, and several others in 1898.

There was a tribe for southern Hunterdon located at Lambertville called the Tuscarora Tribe. There was also “The Red Jacket Lodge,” mentioned above, which admitted the first Indian. And there was a new tribe created in 1890 called Wachusett Tribe No. 120 in Stockton. It’s officers were: Sachem: John H. Book; Senior Sagamore: Mr. H. B. Niece; Junior Sagamore: William R. Knowles; Prophet: William Dean; K. of W.: William Sharp and C. of R.: William R. Reed.16

In 1900, F. Elmer Roberson of Stockton (a one-time member of the Hunterdon County Historical Society), was appointed “District Deputy Great Sachem” for District No. 9, Improved Order of Red Men, comprising lodges in Lambertville, Flemington, Frenchtown and Stockton.17

But getting back to the Wickcheoche Tribe of Red Men—a notice was published on July 12, 1899 identifying the new officers. They were: Prophet: William H. Crady; Sachem: Harry Howell; Senior Sachem: Davis Hanson; Junior Sachem: John W. Scott; 1st Snap; William L. Julliard; 2nd Snap: Lewis R. Hann; 1st Warrior: Corson Hellyer; 2nd Warrior: Walter Edward Bellis; 3rd Warrior: Willard C. Hann; 4th Warrior: George W. Cramer; 1st Brave: Charles S. Rittenhouse; 2nd Brave: Albert B. Kline; 3rd Brave: William Runyon; 4th Brave: Charles W. Hanson; Guard of Wigwam: Nathaniel Britton and Guard of Forest: Pearson W. Hellyer.

In 1900, the officers were: Prophet: Davis Hanson; Sachem: John W. Scott; Sen. Sag.: Corson Hellyer; Jun. Sag.: Amos Apgar; First Sannap: Pearson W. Hellyer; Second Sannap: Louis R. Hann; 1st Warrior: Harry Howell; 2nd Warrior: William B. Prall; 3rd Warrior: Edward Bryan; 4th Warrior: Frederick R. Thatcher; 1st Brave: Charles B. Snyder; 2nd Brave: Richard Barrass; 3rd Brave: Albert Markee; 4th Brace: Grant Sipler; Guard of Wigwam: Nathaniel Britton and Guard of Forest: William H. Crady.

It seems as if by the end of the 19th century the number of officers had multiplied, as if to accommodate a larger membership.

The Tribe’s Last Years

In 1909, the Wickcheoche Tribe of Red Men was meeting in the Deats Building on Main Street, Flemington.18 Skipping ahead to October 31, 1928, we find this announcement:

Wickcheoche Tribe, No. 24, of Red Men opens new headquarters in Flemington. The Tribe purchased the home on Church Street that belonged to Martin Dempsey. The responsible group was: C. C. Smith – chairman; George Granger, Sr.; Harold Everitt; Ellis Stenabaugh; Charles Snyder.

In 1930, the new officers of the Wickcheoche Tribe No. 24, I. O. R. M. were Edward Gary, Sachem; Harry Breisford, senior Sagamore; Ernest Snyder, junior Sagamore; Earl Gary – prophet; Edward Lare, chief of records; William Evans, collector of wampum; Charles Snyder, keeper of wampum; and Andrew Ruple, trustee.19

The Wickcheoche Tribe of Red Men was still going strong in 1932 when it sponsored a grand parade in Flemington, to be held on March 11, 1932, at which many New Jersey tribes participated.20 The parade was to begin at “Red Men’s Hall, Church street,” so the property acquired from Martin Dempsey in 1928 was still in use. Note the very public activity of holding a parade. David Lintz wrote that “most secret societies participated in community parades, events, and celebrations – especially Independence Day parades.” The secrecy was obviously limited to certain rituals at the meetings.

The last reported date of a Wickcheoche Tribe meeting was in 1985, at the VFW building.21 There is no record of when the society disbanded. No doubt a careful search of the newspapers would shed light on this.

Conclusion

A curious incident took place in 1884 giving us a glimpse of the view that tribal members had of the Indians they modeled themselves after:

Someone has placed two large scalping knives in the hands of Counselor, Theodore J. Hoffman, having become very much frightened lest the Sachem of Beaver Tribe would employ them in taking the scalps of some of our inhabitants, especially those of small children. At first the Mayor and Common Council thought there might be some hostility on the part of the chiefs and Red Men of Beaver Tribe; but having come to a knowledge of the design of the organization and especially of one fact, viz., that these Red Men never take the scalp of a good pale face, but of those only belonging to the tribe who have become traitors and unworthy the hunt; beside these pale faces are of the improved order and have a perfect right to this reservation, having a charter from the Great Council of New Jersey. Counselor Hoffman in presenting these deadly weapons to the city authorities asked for a cessation of hostilities until a treaty of peace could be concluded; and also reminding them of the fact that New Jersey and Pennsylvania are known in history to be the only colonies escaping blood shed on the part of the Red Man; therefore it is very probable that these good feelings would forever subsist between the two races.22

With the current controversy over the name of the Washington Redskins, it is important to remember that this sort of thing is nothing new. For all of our history, European Americans have been indulging in a fantasy of the culture of Native Americans, probably for a range of psychological reasons, some of them conflicting. There is certainly admiration for Indian culture, but Indians themselves have benefitted very little from that admiration.

Members of the Democratic Club of 1863, who were in other respects perfectly admirable people, were unable to regard enslaved people as their equals. I believe that is also the case of the Improved Order of Red Men in relation to Native Americans. That is our shared history, but it does not have to be our future.

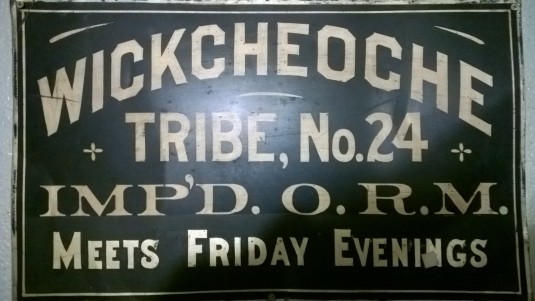

Addendum, March 18, 2016:

As often as I have visited the Hunterdon County Historical Society, for some reason I overlooked a sign that has been hanging on the stairwell to the basement, until archivist Don Cornelius shared it with me. It’s a beauty.

Footnotes:

- Unfortunately, the clipping I have does not include the date or the name of the newspaper, but I assume it was the Hunterdon County Democrat. ↩

- Many thanks to David Lintz, Director of the Red Men Museum and Library for providing information on the Wickcheoche Tribe of Red Men. ↩

- The marriage apparently was not recorded. ↩

- Hunterdon Co. Republican, March 25, 1891. ↩

- There were at least three William Warmans who were contemporaries: 1) of Delaware twp., 2) of Flemington, and 3) of Glen Gardner. ↩

- Highly recommended—Steve Inskeep’s recent book, Jacksonland. ↩

- Hunterdon Republican, March 30, 1892; from abstract by William Hartman. ↩

- Paul W. Schopp informs me that there is a book entitled Great Sachem, which describes the degree ceremonies adopted by the Great Council of the United States of the Improved Order of Red Men. ↩

- I found it at the Graphics Arts Collection in the Rare Books and Special Collections of Princeton University Library, which can be accessed online. ↩

- The Hunterdon Republican, June 2, 1886. ↩

- The Hunterdon Republican, Oct. 12, 1887. ↩

- The Hunterdon Republican, July 25, 1888. ↩

- This was at least the case for the Hunterdon Republican Newspaper and for the Hunterdon Gazette. I also searched online for the Trenton papers, but did not find anything for the Red Men meetings. ↩

- Hunterdon Republican, Jan. 11, 1883. ↩

- Hunterdon Republican, March 5, 1884. ↩

- Hunterdon Republican, Jan. 8, 1890. ↩

- Hunterdon Republican, March 14, 1900. ↩

- I cannot say anything about meetings between 1909 and 1928, because I have been relying on the abstracts of the Hunterdon Republican newspaper by William Hartman, 1856-1930, and Bill has not yet abstracted the years 1910-1927—probably out of sheer exhaustion. My debt to Bill Hartman for the work he has done is enormous. ↩

- Hunterdon Republican, Jan. 15, 1930. ↩

- This is a perfect example of research serendipity. Not long ago, I came across the collection of Hunterdon County Democrats reproduced from the years when the Lindbergh kidnapping and trial were being reported. When I opened the first issue, dated March 3, 1932, I discovered there the story of the Red Men’s parade. Had I tried to find articles about the tribe the old-fashioned way, by looking through the old volumes at the Historical Society, this article would never have gotten written. ↩

- Mr. Lintz wrote that the location of the building was on Route 33. There is no such route in Hunterdon County, although there is one in Mercer County. I suspect that the number 33 is a mistake, and the location was in Flemington on Route 31. ↩

- The Hunterdon Republican, March 12, 1884. ↩

Rich Lowe

November 13, 2015 @ 12:11 pm

My great-grandfather, John A. Laubenstine, died of typhoid fever in 1883 at the age of 31. A notice of his funeral in the Lambertville Beacon dated 23 Nov 1883 states “the deceased was a member of the Tuscarora Tribe of Red Men, which order was largely represented.”

Nancy Parker (Rittenhouse/Adams cross)

December 14, 2015 @ 10:21 pm

Thank you – always glad to get new info on area from which my ancestors arose –

gets me motivated to do more research

Love u

Brian Murphy

January 6, 2016 @ 5:26 pm

Great article, Marfy! I had no idea these societies existed. You taught me something new today! The Red Jacket chapter must have been pretty open-minded to let a real Indian join. Hopefully it was not done just to have him in the membership as a curiosity.

I wonder how much Indian Society “paraphernalia” is still out there waiting to be found

Brian Murphy

Santa Fe, NM

Ruth Hundley

March 23, 2016 @ 10:09 pm

Hello,

I have tonite made the connection with Willam Hoff in this article. It amazes me as to the relations I connect to. Have to visit and spend a month reading!!! Wm. was my 1st cuz 7 times removed :-)

Ruth in IL

Robin Stokes

October 6, 2016 @ 7:45 am

Thank you for this amazing research. I’m having great fun reading your blog.

lester wilson

September 16, 2018 @ 3:31 pm

After seeing a gravestone in Prospect Hill I believe Frederick J Dirking was a member of Wickcheoche Tribe of Red Men.

Margaret Westfield

September 12, 2019 @ 2:49 pm

There’s a building standing in downtown Mount Holly, Burlington County that still carries the IO RM designation obits entablature.

Diane McNew

August 31, 2020 @ 12:04 pm

Thank you for this site. I ran across it when I saw the name Larison, as my genealogy shows marriage into that name and Hunterdon county shows up as well. My last name is McNew from Jeremiah MacKnew of Prince George’s County, MD. I am always looking for information that relates. These secret societies are always so interesting, but their exclusivity and justification begs many questions in looking at histories not only past but present. It’s always about what goes on behind closed doors. Your comments about the plight of Native Americans are astute. Thanks again for your research and writing.

Marfy Goodspeed

August 31, 2020 @ 1:11 pm

Diane, Be sure to check out the Larison family tree. Go to the families page where you will see it listed, and click on the name. Also be sure and let me know if you have any additions or corrections.