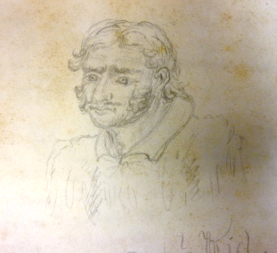

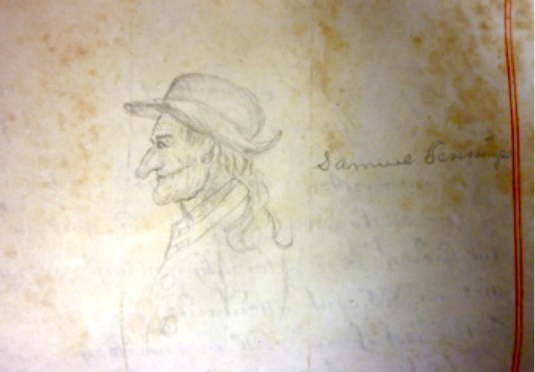

William Kidd and Samuel Jennings

In the previous post, concerning the life and death of Capt. William Kidd, I speculated on who the person was who drew these pictures

Unfortunately, I was basing my conclusions on a faulty citation, which is an egregious error for an historian, amateur or not. I had concluded that the most likely person was John Tatham, who was not only an ardent opponent of Samuel Jennings, but also a strong supporter of Gov. Jeremiah Basse and of the claims of Daniel Coxe, and later the West Jersey Society, to vast tracts of land in West New Jersey. The circumstance I relied on to identify Tatham was my mistaken notion that the drawings were made on a blank page of the minute book of the West Jersey Board of Proprietors. And I made that mistake by relying on my memory rather than verifying the source.

I had first seen these pictures back in 2010, when I was researching the activities of the Board of Proprietors and was reviewing the minutes of their meetings, as recorded in their minute book on file at the NJ State Archives. It has taken me seven years to give these pictures their due—I should not have waited so long. Since I had failed to note exactly where the drawings could be found, I relied on my memory of the research I had been doing on the Proprietors back in 2010.

Here is what I wrote based on that mistaken impression.

Tatham and Jennings

Samuel Jennings was born 1648 in Buckinghamshire, England and became a devout Quaker. Like many English Quakers at the time, Jennings suffered from persecution by local authorities and was eager to join the exodus to the unsettled lands in western New Jersey. He was well acquainted with William Penn, who urged Edward Byllinge to appoint Jennings as deputy governor. (Byllinge claimed the right to govern the province, but was unwilling to leave England.) Jennings arrived in the Province of West New Jersey in 1680 and became a fierce supporter of the “Concessions and Agreements of the Province of West New Jersey,” probably the most liberal foundation document of any American colony. Those who opposed him agreed that Jennings was “a resolute and immovable man.”1

John Tatham had an even more colorful history.2 He was born about 1642 in Yorkshire and became a Roman Catholic priest in France. At some point he returned to England where he had to practice his religion in secret, due to the long-standing hostility of the English government against the Catholic Church. The Titus Oates plot in 1678 probably convinced Tatham to put away his priest’s robes, and to consider relocating across the ocean when the proprietary colonies opened up. He was able to purchase some proprietary shares from William Penn and arrived in America around 1685.

William Penn did not have a high opinion of him. He wrote that Tatham was “subtile & prying & lowly” but also that he was something of a scholar. Despite his dealings with William Penn, Tatham quickly aligned himself with Daniel Coxe, who named him his agent in West Jersey in 1688.

Tatham and Jennings were on opposite sides of a conflict over land and governance in West New Jersey that existed from the beginning of its settlement in 1680, and continued until the surrender to royal governance in 1702. The West Jersey Society got the upper hand in April 1698 when it managed to get Jeremiah Basse appointed governor. One of his first acts was to install his friends, Tatham chief among them, on the Council of West Jersey Proprietors. This gave Tatham access to the minute books, where the drawing of Kidd and Jennings was found. At this time Samuel Jennings was speaker of the West Jersey Assembly, and leader of the opposition to Basse and his followers. In 1699, John Tatham, along with Thomas Revell and Nathaniel Westland, published a pamphlet titled “The Case Put and Decided,” accusing Jennings of “inciting opposition” to the Basse government and court. Jennings answered with “Truth Rescued from Forgery and Falsehood.” The animosity between the two factions was at its peak, but in December 1699, Basse was removed from office and replaced by Andrew Hamilton, who had previously served as governor, and was sympathetic to the Quaker proprietors. He immediately removed Basse’s cronies, including John Tatham, from his government.3

Thus, it seems to me that between July and December 1699, John Tatham was in a position to make those sketches of Kidd and Jennings. And it just so happens that during that time, William Kidd was in prison in New York City. When Jeremiah Basse was still governor, he issued a proclamation calling on all East Jersey inhabitants to aid in the arrest of any of the men serving with the notorious pirate Capt. William Kidd. It seems likely that once Kidd was in jail, Basse and his friend John Tatham went to visit the notorious pirate in his jail cell. Whoever drew his portrait certainly must have done so, as it is so true to his later portrait.

The Portraits Located

So that is the story of Tatham and Jennings. I passed the article on to Joseph Klett, head of the State Archives, who shared it with Bette Epstein, librarian extraordinaire. She was not satisfied with my vague citation, and determined to locate the drawings. But she could not find them in the Proprietors’ minute book. After examining the photos I had taken, she found them in “Acts of the General Assembly” of West Jersey, 1681-1701 (reference number PWESA001). Captain “Kid” appeared on page 17, which was dated 1682, and Samuel Jennings on page 29, dated 1683.

This is an excellent example of how important it is to get your facts straight if you are going to build a theory about something historical. As I noted above, Tatham was a member of the Board of Proprietors in 1699 when Kidd was in jail in New York City, so that gave me a bit of circumstantial evidence pointing to him. But was he also a member of the West Jersey Assembly? I cannot answer that question.4

If he was a member of the Assembly and did make these drawings, then he had to have done them before July 1700, because that was the year he died. If there is reason to think the drawings were made after that date, then John Tatham can no longer be considered as the artist.

It is important to remember that in 1702, the West Jersey Assembly and the East Jersey Assembly were dissolved as a consequence of the surrender of governing rights to Queen Anne, and the unification of the two provinces into one, the Province of New Jersey. As a consequence, it is quite possible that someone had access to a book (the Acts of the West Jersey Assembly, 1681-1701) that was no longer as relevant as it had been before unification. Which means that the person who drew the portraits could be almost anyone. One reason for thinking that the drawings could have been made in the 18th century, or even later, is that pencils were not commonly in use in the late 17th century, although they did exist at the time. But another problem is the label for Samuel Jennings. The style of writing does not resemble that used in the late 17th century. These issues were pointed out to me by Bette Epstein, and I cannot quarrel with them.

There is something else that is intriguing about these drawings, and that is a third portrait that I did not include in the previous article. The main reason I left him out is that he was not identified. Could this be a self-portrait of the artist? Could the attempt at a hat be a clue? Your guess is as good as mine.

Needless to say, I am very disappointed that I cannot be certain that Tatham was the artist. He fits so well into the political zeitgeist of the time. But wishful thinking is not appropriate here. Lesson learned.

Footnotes:

- John E. Pomfret, The New Jersey Proprietors and Their Lands, p. 63. ↩

- An excellent biography of Tatham was written by Henry H. Bisbee, called “John Tatham, Alias Gray” in the Pennsylvania Magazine of History &Biography, vol. 83, No. 3 (July 1959), pp. 253-64. ↩

- I have written several articles here on the early governance of the Province of West New Jersey from the beginning up to 1691, which you can see listed under “Index of Articles.” ↩

- The sources available to me in my office do not provide a list of members of the West Jersey Assembly from 1699 to 1702. When/if I find such a list, I will amend this article. ↩

John Brady

November 4, 2017 @ 4:43 pm

Thank you for unearthing and sharing these amazing renderings! Jennings’ garment and hat have a military character to them perhaps? The records of the Jersey Blues militia show that Jennings was a member of this unit in some capacity. ( Perhaps not fighting given the Quaker’s pacifist views. ) ‘The Story of the Jersey Blues, by Col. Malcom B. Gilman, 1962, Red Bank NJ’

Marfy Goodspeed

November 5, 2017 @ 5:56 am

John, the hat on Samuel Jennings was a Quaker-style hat. The person with the slightly military-looking hat has not been identified. Jennings would never have been a member of the Jersey Blues.

John Brady

November 5, 2017 @ 12:14 pm

He is definitely on this roster of those serving. Can’t vouch for its authenticity nor have I researched the sources it is derived from.

FYI, he signed his name ‘Jenings’. West Jersey deed for his properties also spells his name as ‘Jenings’.

John Brady

November 5, 2017 @ 12:28 pm

I double-checked and I replied too soon – West Jersey deeds spell his name Jennings. However, I do have a signature attributed to him with just one n, not the double n, which chalk up to the variableness of early american life and research!

Goodspeed Histories: The Plot Thickens

November 6, 2017 @ 10:23 pm

[…] Then an explanation on how I came to the wrong conclusion, along with some interesting early West New Jersey history: Who Was the Artist? […]