PART 3 of THE COUNTY HOUSE

During the years 1791-1793, a new courthouse for Hunterdon County was constructed in Flemington. Before it was finished, a complication emerged that connected the courthouse lot with Alexander’s tavern on Main Street.

During the years 1791-1793, a new courthouse for Hunterdon County was constructed in Flemington. Before it was finished, a complication emerged that connected the courthouse lot with Alexander’s tavern on Main Street.

The history of a hotel that once stood on the west side of Flemington’s Main Street has quickly turned into something much more. Part One began with Flemington’s first European property owners and ended with the Revolution. This article goes on from there, but only as far as the 1790s, when Hunterdon County acquired a new courthouse.

Part One of a series on the origins of the west side of Main Street, Flemington, from the courthouse, north.

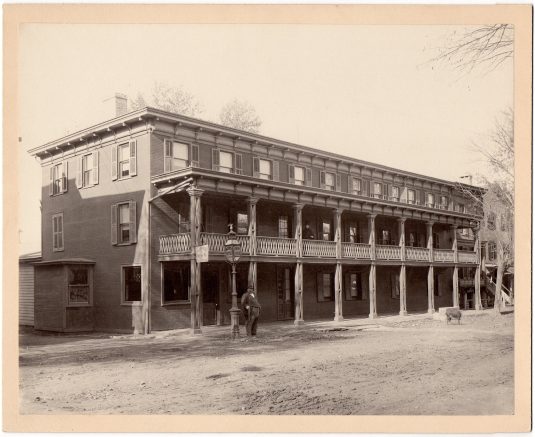

This is one of my favorite photographs.1 The building is Mount’s Hotel on Flemington’s Main Street, across from and a little north of the Union Hotel. It was replaced in the 1970s by the group of shops called ‘New Market,’ built by Don Shuman.