Thanks to the controversial election of 2016 and recent developments in Washington, people are paying a lot more attention to the news, and coming to appreciate the importance of a free press. This got me thinking about newspapers in Hunterdon County.

Back in the 18th and 19th centuries, newspapers were essential because they were the only source of information available. No TV, no internet. Things have changed dramatically since then, but our dependence on good reporting has never been greater. However, in recent years, newspapers have been cutting back, leaving us with fewer good reporters when we need them most.

Of course, in the 18th and 19th centuries, journalistic standards were not very high. There was a great deal of moralizing and sentimentality in the stories that were published, as that was what readers wanted. Running a newspaper was not an easy way to get rich. The old business model, advertisers plus subscribers, did not always work well. But it lasted a long time, until the internet arrived.

Up until 1825, residents of today’s Hunterdon county had to depend on newspapers published in Trenton, the county seat until 1791. By 1825, Flemington leaders, frustrated by the lack of local news, found someone to set up a new newspaper there. That paper was the Hunterdon Gazette and its publisher (and editor) was Charles George. Here is his story and the early history of the Hunterdon Gazette.

Hunterdon in the 1820s

In late 1824, the country was settling down after the euphoria of a visit from the Marquis de Lafayette the previous year. He had even stopped in New Jersey. Then, a month afterwards, in October, the presidential election took place. It was a close one. Andrew Jackson got the most electoral votes, but not enough to win, since there were four candidates. As a result, on February 9, 1825, after Henry Clay gave his support to John Quincy Adams, the House of Representatives chose Adams as president. He was sworn in on March 4, 1825.

Hunterdon County voters were, for the most part, appalled, as Jackson had strong support here. Hunterdon was so strongly tipped for Jackson that it voted for him in all three elections that he ran in, and this was before the Whig-leaning southern half was spun off into Mercer county (in 1838). There was some recompense in the fact that a Flemington lawyer, Samuel L. Southard, who had served as Monroe’s Secretary of the Navy, was kept on by Adams.1

Although Flemington was nothing more than a village in 1825, it was the county seat, ever since 1791 when it was moved from Trenton, due to increasing population in the northern part of the county. Hunterdon was the largest county in New Jersey by population in 1790. Thereafter, from 1800 through 1820, census records show it as fourth largest. But it had a spurt of growth in the 1820s, and was counted as the third largest in 1830, with a population of 31,060.

Even before the Revolution had concluded, Hunterdon residents living north of Hopewell were unhappy about traveling all the way to Trenton to file their deeds and register their wills. In 1780, the county freeholders held their first meeting outside Trenton at the tavern in Ringoes, an important crossroads village. In 1791, the freeholders held their last meeting at the courthouse in Trenton, and their first in a building on a lot in Flemington owned by a Mr. Alexander.2 This was quite possibly one George Alexander who married the daughter of Samuel & Esther Fleming.

By 1825, the economy was beginning to recover from the recession caused by the Panic of 1819. Local attorneys, farmers and businessmen in and around Flemington needed a local paper to keep up-to-date.

As the county seat, Flemington attracted lawyers who had business before the county courts, and merchants who catered to people who came to Flemington to probate wills and estates, or attend the court when suing for debt, or to petition the Board of Chosen Freeholders for a new road or bridge. The only paper available was the New Jersey State Gazette, which, according to John W. Lequear “was brought up from Trenton by the mail carrier on horse-back, a small sheet indeed, with but little news.”3 Flemington professionals and farmers wanted a newspaper that published articles of relevance to them, like what real estate the Orphan’s Court might have ordered to be sold, what horses might be for sale, what races were to be held, and who married or died recently.

A public meeting was held at Neal Hart’s Tavern in Flemington on February 27, 1825 to discuss the problem. We know this because Peter Haward mentioned it in his diary, according to Hubert G. Schmidt. Apparently Haward did not write down what was discussed at that meeting. Schmidt seems to have thought they were still contemplating a newspaper for Flemington, but it seems that a newspaper was already in the works, judging by an observation by its first publisher Charles George who wrote on March 24, 1825 that “the publication of the first paper has been protracted to about one month later than was originally contemplated.”

Who Was Charles George?

Charles George was born about 1795, probably in Philadelphia, and was married by 1821. With wife Mary W. [maiden name unknown] he had at least six children, from 1822 to about 1833.4

Before being recruited to establish the Gazette, Charles George was running a print shop at No. 9 George Street in Philadelphia. Hubert G. Schmidt wrote that, like some of the men who recruited him (Peter Haward and Thomas Capner), George was an English immigrant, whose father was David George of Sheffield, England. However, on May 24, 1826, the Gazette included this notice:

“Died at Dayton Ohio, on the 27th of April at advanced age, William George Esq., formerly of Frankford near Philadelphia.”

Why would the Hunterdon Gazette take note of the death of someone who died in Ohio? I suspect it was because William George was some kind of relative of Charles George, although I have not been able to identify the connection. And I do wonder about Charles George being an immigrant. No doubt his father was, but in the 1850 census, Charles George claimed he was born in Pennsylvania.

The First Issue of the Gazette

Once he arrived at Flemington, Charles George got right to work, and published his first edition on March 24, 1825. The newspaper appeared on a Thursday in the post offices and taverns of Hunterdon County. It was called the “Hunterdon Gazette and Farmer’s Weekly Advertiser.” The second half of the name did not last very long; the last issue to include “Farmers Weekly Advertiser” was published on July 21, 1825. Given that nearly everyone in the county was a farmer, it is surprising that that part of the title would be dropped so quickly.5 Mr. George introduced his newspaper in this way:

Once he arrived at Flemington, Charles George got right to work, and published his first edition on March 24, 1825. The newspaper appeared on a Thursday in the post offices and taverns of Hunterdon County. It was called the “Hunterdon Gazette and Farmer’s Weekly Advertiser.” The second half of the name did not last very long; the last issue to include “Farmers Weekly Advertiser” was published on July 21, 1825. Given that nearly everyone in the county was a farmer, it is surprising that that part of the title would be dropped so quickly.5 Mr. George introduced his newspaper in this way:

“The increasing demand for newspapers, in every populous district of our country, is a cogent argument in proof of their general utility; and the extensive circulation, in the United States, of periodical publications of various kinds, and of newspapers in particular, forms an auspicious criterion of our devoted attachment to the principles of civil and religious liberty: while the unfettered establishment of the freedom of the Press, affords a safe guarantee of the advancing prosperity of our highly favored land.”

This is such a beautifully optimistic and patriotic sentiment! especially that part about “the unfettered establishment of the freedom of the Press.” And it was widely shared in America, as attested by de Tocqueville during his visit here in the early 1830s. Everyone was reading newspapers, or having them read to them aloud. It was the beginning of the golden age of newspapers.

However, Mr. George was keenly aware of the difficulties inherent in publishing a newspaper, the principal one being that people would subscribe but then neglect to pay, leaving the editor to produce a paper from his own funds. But he gently reminded his readers that

“the intrinsic worth of a journal must be the result of time and experience; and will be, in many instances, graduated by the measure and promptness of the support afforded by those whom it is designed to benefit.”

Then Mr. George described for his readers what they should expect to find in his pages:

The HUNTERDON GAZETTE will contain a comprehensive summary of the latest and most interesting intelligence, foreign and domestic. The subjects of agriculture and domestic manufacturers, now occupying so large a share of interest in almost every section of our country, together with the interesting topic of internal improvements generally, will receive that liberal attention which their growing importance so justly demands.

A condensed view of the proceedings of Congress, and of the state legislature, will be given to as great an extent that shall consist with the limits of a weekly sheet. Well written essays on topics of general interest, will be inserted when space shall permit, always subject, however, to revision and remark by the editor.

The claims of literature and the arts will not be overlooked; while a portion of the sheet will be devoted to miscellaneous selections, moral and religious, calculated to improve the mind and enlighten the understanding. The whole designed to render the Gazette a repository of information suited to readers of every class and condition.

It should be noted that editors of the time were notoriously partisan, especially from 1790 to the end of the war in 1815, and then again during the presidency of Andrew Jackson. Even Thomas Jefferson was guilty of making use of a Philadelphia paper to promote his ideas and denigrate his opposition. In this environment, Charles George felt it necessary to let his readers know, up front, that he was taking a slightly different, and far more idealistic, approach.

“We should form an exception to the rule, almost universal in its operation, were we to declare ourselves disinterestedly free from all political bias. Such a declaration would, we doubt not, draw upon us an imputation by no means creditable to our professed candour. We therefore think it due to our readers to state, that while we shall attempt the discharge of our editorial functions with an impartial regard to the people’s best interests, according to our humble conception of the objects in which they consist; we shall not, thereby, relinquish their claim to the enjoyment and exercise of any privilege comprised in the birth-right of every American citizen.”

In other words, George would do his best to be impartial, but would not hesitate to comment frankly on political developments he disagreed with.

What Charles George produced was a weekly paper for Hunterdon County that did provide a fair amount of fluff and filler, but also focused on the concerns of the people who lived in and around Flemington. This was a refreshing change from the content of the Trenton papers. Items pertaining to Hunterdon residents did not appear with great frequency in the Trenton True Emporium or the New Jersey State Gazette.

Examples of fluff and filler were articles on the front page of the March 31st edition: “The Moralist,” “The Ladies Friend,” and “Friendship.” “The Moralist” encouraged the reader not to depend on “the happiness that this world can give,” as it will be as nothing to you when the going gets tough. “Ladies’ Friend” starts with “The Toilet of a Roman Lady.” Where this information came from is not stated, which is surprising given the explicit directions for a well-bred lady of ancient times. This is followed by “The Wife” which waxes ecstatic about the benefits for men of marriage to a supportive woman. Nothing was said about the benefits to the wife. “Friendship” was equally flowery. That was the way of the times. It is not easy to think the way people living in the 1820s did—the world was such a completely different place. So much had not happened yet. And preachers were the rock stars of the day.

Following these items came articles imported from other newspapers. In the 19th century, editors routinely mailed their papers to other editors across the country, allowing their stories to be shared. This was most often the case with “Foreign Articles.” After all, a Hunterdon editor was in no position to gather news from east coast shipping ports, or from the government in Washington. Sometimes these stories were so detailed that it seemed unlikely that most Hunterdon readers would be interested.

Page 3 is where the paper gets interesting, and that would be the case for many years to come. It consisted of the regular column by the editor, commenting on news of the day, plus some filler stories on “Domestic” news from around the country, and then several local notices and advertisements.

In the first issue, there were local notices for two marriages (Silas Vankirk to Delilah Coryell and Samuel Case to Jane Waldron), one obituary (Elizabeth Clark, wife of Rev. John F. Clark), the sale of several lots by Asher Hill and Thomas Capner, an ad for Thomas J. Stout, Blacksmith, a notice from the Flemington Vigilant Society, notice of the dissolution of the partnership of S. D. Stryker and J. H. Anderson, and a notice from the Court of Common Pleas regarding a suit brought by Henry R. Brink against John D. Brink for debt.

Since the paper advertised itself as “Hunterdon Gazette and Farmer’s Weekly Advertiser,” due attention to farmers’ concerns was essential. On the last page of the March 31st issue (page four), following some poetry and extraneous articles, there appeared “Portrait of an American Farmer, from Mr. Biddle’s Address to the Philadelphia Society for promoting Agriculture,” and then a section titled “Agriculture,” devoted to crops and livestock, and especially horses.

I mentioned earlier that it was hard to develop a business model that would support the running of a newspaper on a weekly basis. Income was based on subscriptions and advertising. As Hubert Schmidt wrote: “The subscription rate was to be $2.00 per year, half in advance, providing the subscriber called at the office for his paper each week. Those wanting their paper delivered must pay an extra fee to a delivery boy or man who operated a route by horseback or must pay postage. The Gazette would pay the postage for those patrons who paid a year in advance.” Incidentally, there were no postage stamps in 1825; they did not come into use until 1834. Previous to that, items sent through the mail had to be embossed.

Running a weekly paper was also hard work. A strong young assistant was invaluable. On page 3 of the March 31st issue there appeared this notice: “Wanted: A Lad from 14 to 16 years of age, of good moral habits, as an Apprentice to the Printing Business. Inquire at this Office.”

Flemington, 1825-1830

Flemington was a growing town in 1825. The courthouse had been standing since May 1792. County business was now focused in this village, which meant not only the court and law offices, but also important inns and taverns, new residences, and, gradually, new stores providing merchandise not previously available. By 1826, Charles George wanted to spread the message that Flemington was the place to be, as he wrote on April 19, 1826:

OUR VILLAGE. — the spirit of improvement which for the last few years has manifested itself in almost every country town and Village North and West of us, has at length been revived in some hopeful measure in this place; and only needs the fostering encouragement of a few of our contiguous proprietors, to realize for Flemington the advantages to which, as the seat of Justice of Hunterdon, it is fairly entitled. A few houses, of various dimensions, are going up; and others, we are happy to learn, are strongly talked of.6

The new Methodist Meeting House had been built the previous fall, and new storekeepers were open for business, offering “a very general and extensive assortment of goods, suitable to the season, and calculated to please and accommodate their numerous customers.” But services were still wanting; in an editorial, George put in a plea for “a Saddle and Harness Maker, and a Coach Maker.”

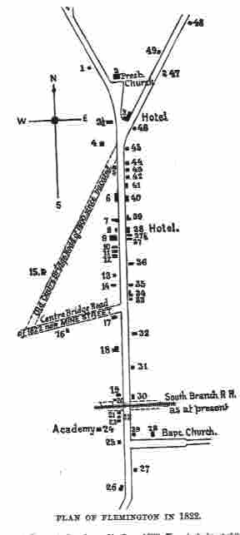

Often in his newspaper, George referred to “the Village of Flemington.” The term Village did not mean the same thing in 1825 as it does today. Now we think of a village as a quaint little place at the intersection of sleepy country roads. But in 1825, the term ‘village’ was an important designation. As you can see from the map of Flemington based on residents in 1822, it was quite well-developed. There were two churches, three hotels and almost 50 buildings all told. (The numbers in the map refer to a list in Snell identifying owners of each lot.)

Despite the disappointment of the election of 1824, there was still plenty of patriotic feeling in 1826 when the country celebrated its 50th Jubilee. People knew the importance of that milestone. Their republican form of government was still an experiment, but despite the political divides, it seemed to be working. Their confidence was expressed in the multitude of Fourth of July toasts given that year.7

Meanwhile, Charles George was obliged to continue his pleas to subscribers to pay their dues. The method of payment was interesting, as seen in this notice George published on November 8, 1826:

Subscribers and others indebted to the editor, all are informed that Mr. Daniel Ent, who delivers the papers, is also authorized to receive money due the establishment, and receipt for the same. This notice is given, that those residing at a distance may avail themselves of the opportunity of remitting with certainty, and without inconvenience. Those who have engaged to pay in WOOD, are reminded that a few cords of good sound hickory would be very acceptable.

On March 12, 1827, Charles George decided to commit himself, and purchased a house lot of 0.59 acres in Flemington from Charles and Margaret Bonnell for $250. It bordered Bonnell’s tavern lot.8 The family was counted in the 1830 Amwell census with Charles and his wife in their 30s, four children between 5 and 10 years old, a girl between10 and 15 years old and a young man, possibly an apprentice, between 15 and 20.

In 1827, it was clear that the newspaper was a success. According to Hubert G. Schmidt, who wrote:

With more advertising, the paper itself was probably making a profit, and the print shop, often a life saver for country weeklies in that period, was doing very well. In addition to job printing, he sold paper, “genuine British ink powder,” etc. Editor George’s new prosperity was shown by a move to larger quarters. On May 16, he advertised, “To rent, the house at present occupied as the office of the Hunterdon Gazette, in a central part of the village, and suitable for the business of a chairmaker, taylor [sic], shoemaker, or cooper.”

A month later he informed his readers that he had moved the Gazette to a new building located between Smock’s Hotel and “the new Methodist Meeting House.” George evidently owned both buildings, and rented out space in both. On June 25, he advertised a “commodious room” for rent on the second floor of his new building. He wrote, “It would make a comfortable office for a professional man, or an eligible stand for a tailor.” Since the ads appeared only briefly as regards both buildings, it seems that he had no difficulty in renting. . . .

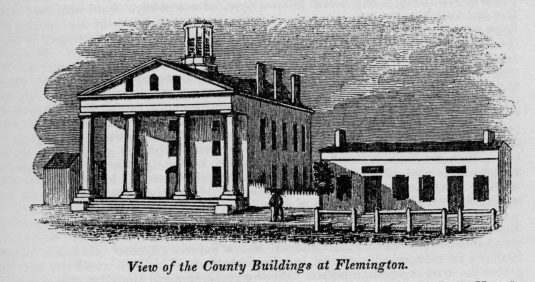

A year later, in 1828, the original court house burned down. (Fortunately, contrary to some statements made later, the records were saved.) This was not necessarily the disaster it first appeared to be. In 1824, members of the Bar had expressed their dissatisfaction with the old courthouse and complained to the freeholders, but the matter was postponed. Residents of Lambertville were so unhappy with it that they proposed that the county seat be moved to their town. How the fire started (some did in fact suspect arson) was never established. Until a new courthouse was built, the one we are familiar with today, the court had to meet in the new Methodist Church.9

By 1834, when Thomas Gordon published his Gazetteer of the State of New Jersey, Flemington was significant enough to merit a lengthy entry in the Gazetteer. Here are excerpts:

The town contains 50 dwellings, and about 300 inhabitants; a very neat Presbyterian church, of stone, built about 35 years since; a Methodist church, of brick, a neat building; and a Baptist church, of wood; two schools, one of which is an incorporated academy, and 3 Sunday schools; a public library, under the care of a company also incorporated; a court-house, of stone, rough-cast, having a Grecian front, with columns of the Ionic order. . . .

The houses, built upon one street, are neat and comfortable, with small court yards in front, redolent with flowers, aromatic shrubs and creeping vines. The county offices, detached from the court-house, are of brick and fire-proof. There are here 5 lawyers, 2 physicians; a journal, published weekly, called the Hunterdon Gazette, edited by Mr. Charles George; a fire engine, with an incorporated fire association.10

On June 4, 1828, while the new courthouse was still under construction, Charles George announced that he had decided to sell the Gazette. He had “met and surmounted . . . the numerous difficulties attendant on the establishment of a country press.” But he had decided to return to Philadelphia, perhaps for family reasons. He did not want to suggest that the paper was not doing well—that would have made it hard to sell. So, he offered a positive view of its condition:

This paper has been in existence more than three years; during which time the numerous difficulties attended on the establishment of a country press, have been met and surmounted. – The paper now stands up on a respectable patronage. About 400 papers are distributed weekly; and it is believed that number will be considerably increased after the Presidential contest shall have been decided.

And in regard to that approaching election, George noted that “This Gazette has held a neutral course on that question—is strictly a county paper, and pledged to no party.”

George claimed that both advertising and job printing were on the increase; all the equipment of the business was “in good order;” and Flemington was a well situated between New York and Philadelphia for a county paper. “The pride of property is on the advance, and considerable improvements are going forward in the village.”

Despite this appealing offer, there were no buyers. That was fortunate for Hunterdon County, as Charles George proved to be an excellent editor.

To continue the story, go to Charles George and the Gazette, part two.

Footnotes:

- Southard constructed himself a law office on Main Street in Flemington, just down from the courthouse, in 1811. It is still standing, and is one of the cutest buildings in Flemington. ↩

- Hunterdon Historical Newsletter, published by the Hunterdon Co. Historical Society, “Our Courthouse,” by Kathleen J. Schreiner, Winter 1978, pp. 241-243, and Spring 1978, pp. 253-255. ↩

- From The Press in Hunterdon County, 1825-1925 by Hubert G. Schmidt. This is a marvelous publication and I strongly recommend it to anyone interested in the history of Hunterdon County’s newspapers. I have relied heavily on Schmidt’s research. I have also relied on abstracts of articles in the Hunterdon Gazette collected by William Hartman. ↩

- Information about his family comes from the 1850 Philadelphia census. ↩

- “The Hunterdon Gazette and Farmer’s Advertiser, 1825-1828″ is now online at Genealogy Bank. But, for now, they only have one issue from 1825, being Vol. 1 number 2, March 31, 1825. I have depended on the abstracts published by William Hartman for items in the March 24th issue. Hartman’s Abstracts of the full run of the Gazette (1825-1866) can be acquired on CDs from the Hunterdon Co. Historical Society. ↩

- Hunterdon Gazette, No. 57: Wednesday, April 19, 1826. ↩

- See “The Jubilee of 1826,” parts one and two. ↩

- Hunterdon Co. Deed Bk 42 p. 44. ↩

- An excellent article about the history of the courthouse can be found in Hunterdon Historical Newsletter, published by the Hunterdon Co. Historical Society, Winter 1978, titled “Our Courthouse,” by Kathleen J. Schreiner. ↩

- Thomas F. Gordon, The History of New Jersey from its Discovery by Europeans to the Adoption of the Federal Constitution (with) A Gazetteer of the State of New Jersey, Trenton: D. Fenton, 1834. ↩

Geoff Raike

February 17, 2017 @ 9:47 am

Hi Marfy

Perfect timing in regards to your second paragraph. Enjoyed this posting very much while having my morning coffee. My first job at 13 was delivering Newspapers and I could easily relate on how difficult is was collecting the $1.25 payment from working adults for their weekly paper.