The Covered Bridge has been a landmark for quite a long time. Next year the bridge will be 140 years old—not bad for a bridge. It has had a lot of work done on it over the years, and some adaptations have been made to allow it to continue standing. I’ve been making adaptations to some of my articles as well. This second essay on the Covered Bridge is adapted from an article that first appeared in the Delaware Township newsletter, “The Bridge,” and from an article published in the Hunterdon Historical Newsletter, Fall 2003 issue.

I’d like to write about some of the interesting people who lived near the Covered Bridge and one in particular who visited.

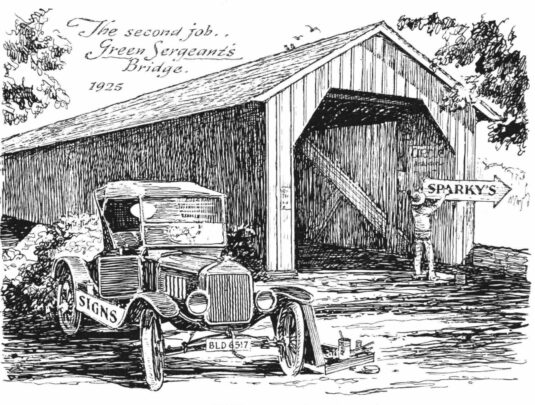

The visitor was Eric Sloane, a famous writer and illustrator of old American folk ways. He published many books on the architecture, tools and practices of 18th and 19th century America. One of them was Return to Taos: Eric Sloane’s Sketchbook of Roadside America, published in 1960 by Funk & Wagnalls (now out of print), in which he described a return visit to the Covered Bridge. This return trip was made in 1959, just before the bridge was torn down and rebuilt. He described the bridge as “gleaming severely white through a glen of maples.”

Sloane’s first visit was in 1925 when he was traveling from Flemington to New Hope, earning his way by painting signs. One of the signs he painted was for a man known in the neighborhood as “Spark-plug” or “Sparky.” Sparky had a road house “at one end of the bridge,” and Sloane’s sign, which was attached to the bridge, served to direct traffic to it. It was a large white sign in the shape of an arrow. At that time, in 1925, the bridge was covered with signs—circus posters, advertisements for New Hope shops, etc., which were all gone by 1959. Sparky tried to pay Sloane with some of his “home-made bottled goods,” but Sloane preferred cash—$10.

It appears from the illustration in Sloane’s book that the roadhouse was just to the right on Upper Creek Road as you head west. According to Blanche Carl, the roadhouse was the stone house just west of the bridge. This conflicts with what Eric Sloane was told by “an old fellow” in 1959, who recalled that Sparky’s place was torn down in 1926 when he (the old fellow) bought the property. That would have been the barn across the road from the stone house. This must have been a mistake of Sloan’s (or perhaps the ‘old fellow’s), since the old man bought the place in 1936, not 1926.

“The old fellow” was Dr. Edward H. Gelvin, who lived in the small stone house just west of the bridge. Dr. Gelvin was a Presbyterian minister for 60 years until he retired in 1955. That was probably about the time he and his wife celebrated their 60th wedding anniversary, as shown in an undated news photo. As they talked, Sloane listened to the sound of cars driving over the loose wooden planks of the bridge. “I took the job of caretaking here,” the old man said, “and they made me a sheriff [probably deputy sheriff] so I could collect some sort of a salary.”

Shortly after World War II, Henry and Mary Brown Burget were married by Dr. Gelvin in the Gelvin house. According to Henry Burget, this was the house where his wife Mary was born. Mary Burget was the daughter of Edward C. Brown (1886-1970) and Kathryn Stryker (c.1890-1963). Ed and Kathryn Brown had five children: William, Mary (who died in 1997), Louis, Richard, and Joyce.

Ed Brown was the son of William C. and Jennie Gulick Brown. After his father’s death, Ed inherited part of his father’s property, while he and his widowed mother sold an adjoining 18 acres to his sister Ida J. Smith in 1920. Well before that time, Ed Brown began a hatchery business in a building across the road that is no longer standing; only the foundation remains. He prospered at the hatchery business and about 1920, when Mary was one year old, he moved to a property in Sergeantsville where he could put up several large hatchery buildings. Hatcheries were a big business in Hunterdon County in the early 20th century. In 1892, Joseph Wilson of Stockton figured out that he could ship day-old chicks by train and have them arrive safely, because day-old chicks do not eat. He quickly developed a thriving business. Demand for day-old chicks from Hunterdon County was so strong that brooder houses and hatcheries were popping up on farms all over Delaware Township. But Ed Brown was one of the most successful.

In 1921, Ed Brown sold his house and barns by the bridge to Katie L. Bennett, wife of Frank C. Bennett. She owned the property up until 1936 when she and her husband sold it to Dr. Gelvin. So who was Sparky? And where exactly was Sparky’s roadhouse? Henry Burget agreed with Dr. Gelvin that it was across from the Gelvin house, where the Brown hatchery was. But the drawing by Eric Sloane doesn’t make sense if that is the case. Perhaps Gelvin’s memory was at fault.

Since first writing this, I have learned from Blanche Carl that when she was a girl, the house was owned by Frank Bennett. Her father, Herb Roadenbaugh, would stop there “for drinking purposes.” Blanche would wait outside in the car, and after a little while her father would return carrying a bag of candy for her. This was probably toward the end of the days of Prohibition. Blanche did go inside once or twice and remembers the place as a home with only one or two people there, not as tavern hang-out.

Around 1960, the well-known New Jersey folklorist, Henry Charlton Beck wrote an article for the Star Ledger about his visit to the Covered Bridge and his conversations with Dr. Gelvin. According to Gelvin, he was able to buy the house for less than the asking price because the owner (Mrs. Bennett) “wanted to displace a bootlegger who had a still in what now is the parlor.” That must have been Sparky, and it confirms Blanche Carl’s memories. As for the claims that the roadhouse was the old hatchery that was torn down, I suspect Dr. Gelvin and Henry Burget both preferred that the lovely little stone house not be associated with illicit drinking.

The Brown-Gelvin house was built well before 1833, when Charles Sergeant mentioned it in his will as “the lot whereon Joseph Slack now lives.” I have been doing some frustrating genealogical work that has led me to suspect, but not allowed me to prove, that the wife of Peter Sibley, the old carpenter who worked on the bridge, might have been the daughter of this Joseph Slack, who fought in the War of 1812 and died in 1854. He and his wife are supposed to be buried in the Rake Cemetery, but I have not found their stones.

Dr. Beck and Dr. Gelvin were both a little gullible when it came to old stories, but they didn’t have the tools we have today to research old families. Dr. Gelvin claimed that his house was of the type known as a “Dutch stone pile,” which meant “it was built without taking measurements.” I have no idea where he got that notion, but he might be right about the lack of measurements. The house is charmingly irregular.

In 1833, Charles Sergeant bequeathed the house and lot to his eldest child, Elizabeth Reading. during her widowhood, and then to her son Charles. Elizabeth Sergeant had married William Reading in 1812; he died in 1831. Elizabeth was a head of household in the Delaware Twp. 1840 census. By 1850, she was no longer living with son Charles, and from what I can tell from other census records, Charles had moved away from “Sergeant’s Mills” by that time. I used to be certain that the Elizabeth Reading who died on 18 January 1873 and was buried in the Reading Cemetery in Delaware Township was the wife of William and mother of Charles. I’m not so sure now, since I have failed to locate her in the census records of 1850-1870. However, the gravestone in the Reading Cemetery states that she died age 80 years 1 month and ten days, which is the right age for the daughter of Charles Sergeant.

It will take a trip to the Search Room to complete the chain of title from Elizabeth Sergeant Reading to Edward C. Brown. Perhaps someday—

As for tracing the house’s history backwards from Charles Sergeant, there is no way to go further, since it stood on the large farm that belonged to Charles Sergeant and before him to the Opdyckes. Because it is such a small house, it must have been intended for mill workers. It may, however, have been home to a slave named Robbin. In 1777, Samuel Opdycke’s father John Opdycke bequeathed him a negro called Robbin, a cow and a windmill. According to Egbert T. Bush, Robbins “was considered exceptionally faithful and competent, capable of attending to the mill on occasion.” As a consequence, when Robbin died, he was buried behind the Opdycke house and given a small gravestone. No one knows if Robbin lived in the little stone house next to the bridge, but it seems entirely possible.1

During the 19th century, there was little threat to the bridge from traffic. There were heavy wagons carrying stone from the Raven Rock quarries, and grain to Sergeant’s mills, but that was not sufficient to threaten the bridge. In fact, it was such a comfortable quiet place, that weary folk riding their wagons home after an evening imbibing at the Sergeantsville Hotel were known to enter the dark bridge late at night, and, thinking they’d arrived home, stop and fall asleep on the bridge, no doubt to be awakened by other weary travelers behind them.

Next post: The Covered Bridge and the Age of the Automobile

- I will be publishing Mr. Bush’s article on the neighborhood of “Sergeants’ Mills” as well as his article on the Covered Bridge very soon. ↩

CRAIG C. SERGEANT

November 4, 2011 @ 10:35 am

Love the new expanded website!! It has this Sergeant family updating old records where we can. My grandfather, George Washington Sergeant was born in Raven Rock (2/7/1877) and my father, Raymond Edward Sergeant was born in Lambertville (9/25/1901).

Craig Sergeant, Fair Haven, NJ.

Marfy Goodspeed

November 4, 2011 @ 2:31 pm

Thank you Craig. Any chance you can tell us who your great-grandfather was?

Joyce Kintzel

April 15, 2013 @ 8:30 pm

I am thrilled to have stumbled onto your website while I was looking for information on an ancester by the name of Gilbert Wheeler. I was born at home in West Amwell Twp., (a long time ago), was raised in Delaware Twp, (Dilts Corner, Headquaters and Rosemont). Upon marrying a Lambertville man, I spent the next 45 years in town, raising two daughters. Now retired to Lewes, DE. I just finished reading your article on the Covered Bridge! As many times as I’ve crossed that bridge, spent time fishing in the creek under it, I had no idea of it’s history. I did know sweet Mr. Gelvin and his frail wife tho! Great research. I so appreciate it and will bookmark this site so I can come back to it and wade thru all the rest. Thank you!!!!

Marfy Goodspeed

April 16, 2013 @ 7:17 am

It’s wonderful to hear from an old-time Delaware Twp. resident. I’m so glad you enjoyed the site. If you search on Gilbert Wheeler, you’ll find some information about him too.

Margery Brown Fisher

October 6, 2015 @ 10:30 pm

This was a thrill to read as I am the great granddaughter of Ed and Kathryn Brown. Grand pop & Grammy Brown. I went to Delaware Twp. school and Sergeantsville Methodist Church. My cousin, Eileen Goodwin still lives in Sergeantsville and may know additional history regarding the covered bridge.

I now live with my husband, Dr. Robert Fisher, in Green Bay ,Wisconsin. We are hoping to capture another Super Bowl Trophy.

Thank you.

Maggie Fisher

Robert Strohmeier

February 14, 2016 @ 12:13 am

Hello, Robert remembered very well about the old bridge (Covered Bridge). I drove very often

for go to Flemington from our old house on Route 519 and our brother and sister went to Delaware School. Our phone number is 408-600-0908. I lived on the farm for over 22 years. My parent was Frederick & Bessie Strohmeier. I have a frame picture of Covered Bridge before damaging by

heavy dump truck, dammit.

Please contact us, thank you for your kindness.

Robert Strohmeier

February 16, 2016 @ 3:24 pm

Dear Sir: I have no idea number of house, R.D. #2, Stockton, New Jersey. What happened is

house today. I leaned the house was torn down. Why?

Robert F. Strohmeier