This is the third installment of a short history of the last covered bridge in New Jersey. The first installment is here and the second one here, and addendum here.

An unanticipated threat to the bridge arrived in the early 20th century when automobiles began to be widely used. Little damage could be done to such a solid structure by a horse and wagon. A car or truck, on the other hand, could do quite a lot.

For drivers, the biggest challenge was dealing with the single lane of traffic through the bridge. With so little sight distance, drivers found it necessary to stop and honk before entering the bridge. This practice was still being used in the mid 1950s when Helen Carl Maliszewski and Kay Sherman Larson were riding through the bridge with their parents.

The 1930s

In 1935, Egbert T. Bush wrote that a few years previously, the bridge had caught on fire but was rescued by a neighbor.1 That neighbor was probably the ever-vigilant Dr. Gelvin. Bush did not explain how the fire got started. Given the massive timbers used for the truss structure, it seems more likely that the fire was started on the siding. Was it accidental or deliberate? We are left to wonder.

The fire may have been the reason for major repairs made to the bridge in 1932 by John Scott, an engineer who built many of the metal truss bridges that still remain in Hunterdon County, including Peck’s Ferry Bridge in Delaware Township, now on the National Register. Scott claimed that after his repairs were completed, the Covered Bridge would take 40 tons and would last that long (in years, I presume). Unfortunately, it couldn’t and it didn’t.

One reporter has written that the work on the bridge combined with the fact that two other covered bridges in New Jersey were demolished made many people aware that they had a treasure that needed protection. The other bridges were located in Somerset County and were replaced with modern steel bridges. New Jersey once had as many as 75 covered bridges.2 With the Somerset bridges taken down, only three were left standing, two of them crossing the Delaware River to Pennsylvania.

The Flood of 1955

During the flood of 1955 (the after-effect of a hurricane), the two covered bridges over the Delaware River, at Raven Rock and at Columbia, were swept away. The Green Sergeant bridge was undermined, but apparently the damage wasn’t obvious. It was not until the county road department made an inspection in 1959 that people realized how much the bridge had deteriorated. The County Engineer recommended replacement, as had happened with all the other covered bridges. But residents began to put up resistance.

The Bridge Comes Down

Then the moment of truth arrived in January 1960 when a truck with a heavy load hit the bridge, probably coming down the hill on Route 604 just a little too fast. It is thought that the truck far exceeded the eight-ton limit on the bridge. The result was a bridge with a slouch, leaning precariously to one side.

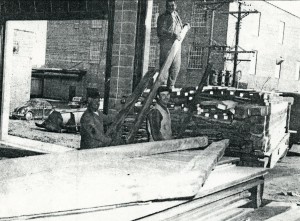

The bridge was closed to traffic immediately, and not long afterwards, the county road department dismantled it, in preparation for construction of an entirely new bridge. Meanwhile, a temporary (and modern) bridge was erected to allow the road to stay open.

The Road Department’s plan was not well-received in Delaware Township and surrounding communities. Almost immediately, local people organized themselves into the Green Sergeant Covered Bridge Association and got national attention for the plight of New Jersey’s last covered bridge. Eric Sloane noted that while his book (Return to Taos) was in preparation, the old bridge was torn down, but “the pieces were saved by a group of Hunterdon County residents.” This was not quite true, since it was the road crew that saved the pieces, but the concerns of those residents probably encouraged them to take care.

The Camden County Covered Bridge

I have noticed over the years, and this is probably not a new phenomenon, that people get pretty attached to certain structures in their environment. In a recent story on the Covered Bridge published in the Star Ledger (here’s the link), there were several comments from residents of Camden County where another “covered” bridge is located. This bridge was constructed by a developer in the 1950s to make his development more appealing. It is technically not covered because the sides are open, and of course, it is not a bona fide 19th-century structure. But that makes no difference to the people who drive over the bridge. It is their covered bridge and they resent the notion that the Green Sergeant Bridge is the only covered bridge in New Jersey. Truth to tell, I respect their passion, if not their logic.

Where Did the Pieces Go?

But back to our bridge. According to Gary Hinesley, Mildred Cotton, one of the more passionate members of the Association, who owned the stone house just east of the bridge, said that timbers from the old bridge were stored on her property, and that she would keep them unless they were used to reconstruct the bridge. However, a photograph in the Hunterdon County Democrat shows road workers unloading the timbers at the County garage. One news article stated that the siding and the roofing were stored in a local barn.3 The Cotton property has a small barn across the road from the house.

Among the many visitors to the covered bridge was the famous Jerseyologist (is that a word?) and author Henry Charlton Beck. While he was there, he struck up an acquaintance with Dr. Gelvin. Beck made a visit after the bridge had been taken down but before it had been rebuilt, and wrote: “Now with the bridge removed and with its timbers being reclaimed, carefully numbered, from a nearby field, it is to be put back where it was.” So perhaps Mrs. Cotton was right–perhaps the timbers were “reclaimed” from the county garage.

The Association

I do not have access to the incorporation papers of the Association, so cannot tell you right now exactly when they organized. It appears to have been not long after the bridge was dismantled, and was no doubt seen as a way to strengthen opposition to a modern replacement bridge.

Most of the original members were residents of Delaware Township. Here are their names, as listed on a plaque that is kept in the Delaware Township Municipal Building: Eleanor F. Stone, president, and Edward M. Stone, Walter Macak, secretary, and Carolyn Macak, Clinton B. Wilson, treasurer, Chester B. Errico, Vincent Abraitys, Raul Tunley, Donald and Beverly Jones, Alice and Howard Sample, Mary and Anthony Zega, Geoffrey Roberts, Berthold A. Sorby, Millie Cotton, Frank H. Curtis, Anan and Robert Thayer, Louise and Bernard Douglas, Evelyn and Frenar Alley, Edna and Clarence Horn, Mary and Harry Burget, Harriet and Henry Fisher, Maurice V. Brady. The names are worth noting since they were all civic-minded people who supported the Township in many ways besides saving the bridge.

The State Highway Commission

Before the Association was formed, a core group of people managed to get an injunction to stop any construction on a new bridge by the county. But the injunction had a deadline. While the clock was ticking, Association members (probably led by Donald Jones) persuaded the State Highway Commissioner, Dwight R. G. Palmer, that state funds would be well-spent on reconstructing the old bridge. On the day that the injunction was to expire, Commissioner Palmer announced that the bridge “is susceptible to restoration.”

In a way it is surprising that the Highway Commission, predecessor of the DOT, got involved at all, since the bridge was located on a very local road (even though designated a county road). But the argument for preserving such a unique structure must have been compelling to Commissioner Palmer. Palmer himself was a remarkable man, and I encourage readers to learn more about him. Why he doesn’t have his own page on Wikipedia is a mystery to me.

I do not know if Commissioner Palmer had the final resolution in mind when he made his announcement, but a compromise was soon reached between the Association, the Freeholders and the State. The state highway department would fund the cost of reconstructing the original bridge, and the county freeholders would build a new, parallel bridge, in a style that was supposed to be compatible with the original bridge. Each bridge would allow for one-way traffic, one going east, the other west.

Next Post: Conclusion.