My last article described the political turmoil in Hunterdon County in the 1850s. There was another kind of turmoil going on at the same time, an economic one. For Hunterdon that meant a local bank was needed.

The Economy in the 1850s

The building of railroads, bridges and roads, the construction of mines and opening of new stores and factories was changing Hunterdon’s landscape.

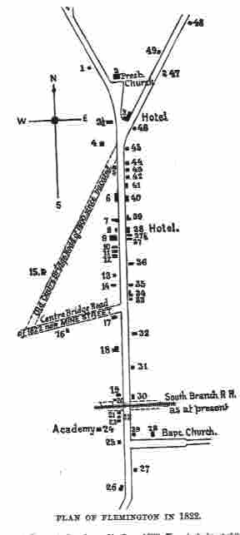

One way to see this change is to compare the maps of Flemington made in 1822, (published in Snell’s History of Hunterdon County, p.329) with the one published on the 1850 map of Raritan Township. The town had grown significantly.

What this growth depended on was a source of credit. Prior to 1836, that source was the Bank of the United States and the banks chartered by state legislatures but governed by the US Bank. As I wrote in a previous article, “1837 in Hunterdon,” that situation changed thanks to President Jackson’s decision to remove federal deposits from the Bank of the U.S. and send them instead to certain select State banks.

There was no longer a central bank to exert discipline on the other banks, which meant that banks tended to lend more than they had gold or silver, known as ‘specie,’ in their vaults. For a while they could get away with it, but for only for a while. When Jackson issued his “Specie Circular,” which required that properties in the new territories to the west be paid for in gold or silver, rather than paper money, the economy crashed. That Crash of 1837 slowed things down, but only for a while.

Flemington Needed a Bank

As you can see from the maps above, Flemington residents needed bank loans as much as the rest of the country. But there were no banks in town. In fact, a search of the Hunterdon Gazette produced very few references to banks in the 1840s and 1850s. They usually referred to the banks of creeks or the canal.

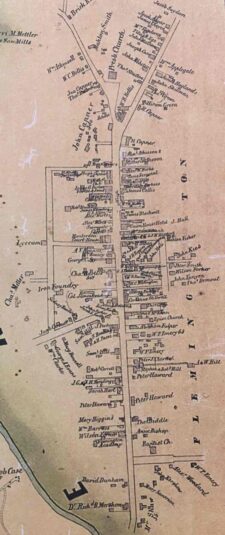

One exception was a bank that was not really a bank at all. It was the New Hope Delaware Bridge Company, which was created in 1812 to raise funds for building a covered bridge to replace Coryell’s Ferry, connecting New Hope and Lambertville. It behaved like a bank and issued its own notes, but in 1848 it crashed. A letter to the editor of the Gazette stated that the Company had not redeemed a note since 1820. I found a picture online of one of its $1 notes, which was auctioned off in 2011 for $195.50.1

About this time, an application was made to the Legislature to charter a couple of banks for Hunterdon County. Legislation was passed on February 27, 1850, establishing two banks in Flemington. One was called “The Tradesmen’s Bank” with Charles T. Cromwell, president, and the other was the “Bank of North America,” with L. I. Merriam, president & John C. Coon, Jr. cashier.

An aside: John C. Coon was the proprietor of a jewelry store in Flemington, who advertised frequently in the Hunterdon Gazette. Here’s an example of his style, published on December 20, 1854:

“The Flemington Jewelry Store Revived! Defiance to the Whole World.

“When Greek meets Greek, then comes the tug of war.”

THIS ISSUE will bear the beaming intelligence to the good people of Hunterdon County, and the rest of Mankind, greeting: That an Era, a crisis has arrived in the Jewelry business in Flemington; old things have passed away, and a new Programme has been introduced, which will make some of the old long-winded, high-priced dealers in JEWELERY [sic] stare! Hence it is incumbent on all to read, and reject false pretension, and cleave to those that delineate “stubborn facts and beneficial truths,” in this wonder-working age, when every day brings something new.”

And he goes on at length for nearly a whole column. This was the first of his many ads in the Gazette. At the time he was only about 24 years old, meaning he was 20 years old when the Bank of North America was created, and he was made cashier. It does make one wonder if despite its grandiose name, the Bank of North America may not have been all that sound.

Not everyone was enthusiastic about creating a bank. In fact, Democrats generally, following the lead of Andrew Jackson, were not inclined to appreciate banks. On October 8, 1851, the Gazette’s editor copied a comment made by the State Gazette of Trenton:

“Another Bank. A Certificate has been filed, pursuant to the requirements of the Free Banking Law, for a new Bank, with a capital of $50,000, with the privilege of increasing to $500,000, to be called the Tradesmen’s Bank, and to be located at Flemington. From what we can learn, the citizens of Flemington have little or no interest in this new enterprise.”

The Gazette’s editor commented:

We rather guess the above is NEWS to many of the “citizens of Flemington.” Why the originators have kept their design so shady, is a profound mystery! No matter, democratic, anti-Bank Hunterdon, is in for a Bank at last.

And on December 8, 1852, the editor of the Gazette noted that the bills of the Bank of North America were “redeemed at par at their Banking House in Flemington, NJ, and also at John Thompson’s, corner of Broadway and Wall streets, New York City.

But this activity was not enough to support two new banks—not yet. They failed to collect the assets they needed, according to an 1853 report by State Banking Commissioners, and had to close their doors.

The Special Charter

In 1854, supporters of a new bank tried again, this time with more success. But the bank was chartered and in operation for several months when it ran into difficulties caused by the requirements of the banking law. As a result, the Directors and Stockholders petitioned for a special charter, and a bill for such was introduced.

The February 7, 1855 issue of the Gazette reported that the bill to charter the “Hunterdon County Bank” was taken up on its third reading in the State Senate. The Senator from Hunterdon County, Alexander V. Bonnell, stood up to speak on its behalf. This was none other than the man who would in the coming October chair the “Mass Meeting” of the American Party (see “Choosing Sides”), and he spoke at length:

Mr. PRESIDENT ─ Before this bill is put upon its final passage, I feel it to be my duty to state my reasons for recording my vote in its favor. When I was before the people in the county of Hunterdon as a candidate for the position I now have the honor to hold, it was well known that I was an advocate of special bank charters, and although some opposition was raised to me upon that account, I was fully sustained. I therefore feel fully assured that my vote upon this bill will meet with the approbation of my constituents. It has been intimated, that those who are advocating special bank charters are influenced by personal considerations. So far as myself is concerned, I have not owned a share of bank stock for the last twenty years, and if the bill now before the Senate becomes a law, I do not care to be a stockholder in the institution, and if one at all, it will be to a very small amount. The only benefit I expect to receive from the chartering of this institution is that which I will derive in common with all the businessmen of Hunterdon county I represent, feeling the necessity for a sound and well conducted banking institution; such an institution as will at the same time guarantee a proper safety to note holders, and promote the best accommodation to our businessmen, that I advocate this measure. To secure so important an interest, a departure from the General Banking law is manifestly necessary. It is true, Mr. President, that it is difficult to combat the General law with arguments; it is a beautiful theory, but how many beautiful theories that have had their run for years, are now numbered with the fallacies of the past.

That was just the introduction! He called attention to past bank history in the county, showing the challenges of operating a local bank under the laws then in effect.

The county of Hunterdon has enjoyed the honor of having had within her limits three of the legitimate offsprings of the General law. The first two were ostensibly located in Hunterdon, but really in Wall street, and were managed by Wall street brokers, who commit their depredations upon the business community, and then come to New Jersey to have them legalised. The third was organised by our own citizens for the purpose of doing a fair bona fide banking business. The bill now before the Senate, gives this third institution a special charter. The eight months that this bank has been in operation has proved its entire inability to meet the wants of our people, and is it the fault of those who control it? No, it is the fault of the law.

Then he discussed the opposition by the Democratic party, which in this case was insufficient to defeat the bill. It passed by a vote of 12 to 5. The charter was officially granted on April 5, 1855. Stock sales began for 4,000 shares, intended to raise a capitalization of $100,000. The Gazette of July 18th featured a notice from “the Commissioners appointed by the act of the Legislature of New Jersey at its last session” stating that a subscription was being opened to sell shares in the bank for $25 each in order to raise the $100,000 needed. The commissioners were George A. Allen, Andrew G. M. Prevost, William. R. Moore, Hiram Deats, Samuel C. Eckel, Bennet VanSyckle, John Runk, John S. Williamson, Alexander Wurts, Charles Bartles, and John G. Reading.

Wealth in Flemington

Many of these Commissioners were very wealthy, so it is not surprising they would be anxious to get a functioning bank in Flemington.

The 1860 Census

We can find out a lot about wealth in the 1850s by looking at the census for 1860, because that year, probably as a result of the crash of 1857, it was determined that getting the value of real and personal property would be a good idea. For historians this is wonderfully helpful.

I was surprised to discover that in Raritan Township, which at the time included Flemington, the richest person was a minister, Rev. John L. Janeway. His real estate was worth $150,000! although his personal assets were a relatively modest $10,500.2

The man with the most wealth altogether was attorney Charles Bartles, Esq., with $80,000 in real estate and $60,000 in personal wealth. Not far behind him was merchant John G. Reading, with land worth $79,450 and personal wealth of $22,000. The next three richest people were farmer Hugh Capner ($69,00/$13,000), widow Caroline Sloan ($40,000/$33,500), and merchant William P. Emery ($40,000/$20,000). Bartles and Reading were bank commissioners, but the last three were not. Also not on the list of Commissioners was John C. Hopewell, who was assessed with only $25,000 worth of real estate and $1,500 of personal property. But ten years later, in 1870, his real estate amounted to $115,000 and personal property of $60,000. It appears that the Civil War did no harm to Mr. Hopewell.

Civil War Taxes

Another way to measure wealth is to look at income taxes. Waging a civil war can be very expensive. Up until the 1860s, there was no such thing as an income tax, but the war changed all that. A Revenue Act was passed in 1861, and quickly amended with a Revenue Act of 1862 to raise more money. (I have previously written about the Civil War Tax Assessments, in three parts.)

Because people were not yet accustomed to paying income taxes, the Hunterdon Republican actually took it upon itself to publish a list of taxpayers and the amount they paid, although this did not begin until the war was over and continued for the four years after the war ended. If that were done today, people would be pretty upset, but I’m very glad it was done because it tells us that John G. Reading was the richest man (or at least the one with the highest taxable income) in Flemington in 1867 and 1868, and the third richest in 1869. Also on the list of very rich people were, of course, Charles Bartles and John C. Hopewell.

Bank Notes & Counterfeits

Unlike today, in the 1850s there was no national currency, thanks to the actions of President Andrew Jackson who pulled the federal deposits out of the national bank and sent them to select (“pet”) banks in the various states. (See “1837 in Hunterdon Co.”) By the 1850s the number of local and private banks in the country had grown enormously. They were supposed to be backed by “specie,” i.e., gold and silver in various forms. Even though the supply of gold had greatly increased, thanks to the discoveries in California, it was not enough to support all the new banks.

In the early 19th century, it was fairly common for recorded deeds to state that the payment for land should be made in gold or silver. But people did not keep piles of gold or silver at home waiting to be used for large purchases like real estate, especially people in rural areas like Hunterdon, far from the banking centers of New York and Philadelphia. A substitute was needed so people found several. Consequently, the language of deeds was modified to read “for and in consideration of the sum of $__, good and lawful money of the United States.” Sometimes they didn’t even bother to add the term ‘lawful.’

This money of the United States was usually a promissory note of some kind. One kind was the personal promissory note, given by one person to another, usually a farmer needing to pay for supplies, or a merchant needing to pay for goods from a wholesaler. But these notes were only good if there was trust on both sides. A better solution was the bank note, a promissory note written by a bank. These were far more popular because they did not rely so much on personal trust and because they were anonymous.3 Bank notes were much more easily used in places far from the issuing bank.

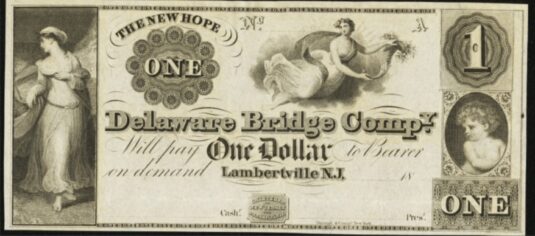

The Hunterdon County National Bank issued its own notes, one of which was found by Hunterdon Co. Historical Society Archivist, Don Cornelius, while looking through the Capner papers. Note that it was treated like a personal check, made out to John B. Rockafellar by Hugh Capner.4

The Hunterdon County National Bank issued its own notes, one of which was found by Hunterdon Co. Historical Society Archivist, Don Cornelius, while looking through the Capner papers. Note that it was treated like a personal check, made out to John B. Rockafellar by Hugh Capner.4

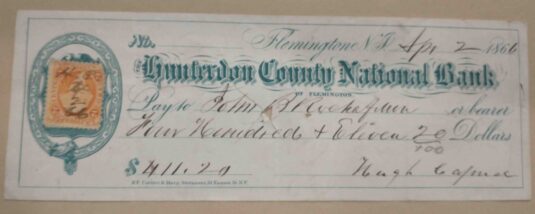

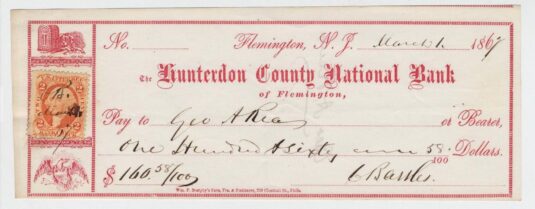

Here is another bank note issued by the Hunterdon County National Bank in 1867. (I found it online in the collections, of all places, of the British Museum.) This note was made out to George E. Rea by Charles Bartles. I cannot say if the bank issued notes before it became a national bank in 1865; most likely it did.

Here is another bank note issued by the Hunterdon County National Bank in 1867. (I found it online in the collections, of all places, of the British Museum.) This note was made out to George E. Rea by Charles Bartles. I cannot say if the bank issued notes before it became a national bank in 1865; most likely it did.

The problem with bank notes was that by this time, printers had developed very efficient machines and artists found that their services were in demand for creating counterfeit bank notes. They were often quite lovely. In fact, during the years leading up to the Civil War, there were nearly as many counterfeit notes in circulation as legitimate ones.5

One of the consequences of this multitude of phony notes was that a new business got started—the publication of “Detectors,” which were books that described all known counterfeit notes. The Detectors also rated banks on their solvency. One of those publishers, John S. Dye of Wall Street, New York, advertised in the Hunterdon Gazette on March 11, 1857, with a remarkable lack of modesty:

DETECTING COUNTERFEIT BANK NOTES. Describing Every Genuine Bill in Existence and Exhibiting at a glance every Counterfeit in Circulation!! Arranged so admirably, that Reference Is Easy and Detection Instantaneous. No Index to examine! No pages to hunt up! But so simplified and arranged, that the Merchant, Banker and Business Man can see all at a Glance. It has taken years to make perfect this GREAT DISCOVERY. The urgent necessity for such a work has long been felt by Commercial men. It has been published to supply the call for such a Preventive and needs but to be known to be Universally Patronized. It does more than has ever been attempted by man. It describes every Bank Note in three Different Languages., ENGLISH, FRENCH AND GERMAN. Thus, Each may read the same in his own Native Tongue.

The Crash of 1857

The great expansion of business and banking in the 1850s meant that far too many banks were providing credit when they did not have the assets to cover their loans. The inevitable happened, and in September of 1857, banks were forced to suspend payment of specie for notes that were turned in. This was, in most cases, a temporary condition but did nothing to encourage confidence in the banks.

At first, the Hunterdon County Bank bucked the trend. On October 7, 1857, the Hunterdon Gazette published a notice from William Emery, Cashier of the Hunterdon County Bank:

NOTICE is hereby given, to all whom it may concern, that the notes of the Suspended Banks of New Jersey and Pennsylvania, will be received in payment of notes at the Hunterdon County Bank.

The editor of the Hunterdon County Democrat was sure that the crash was the fault of the Republican party. On the same day, he wrote:

“We can look around us, and, in the financial as well as the political world witness the effects which a brief elevation of our bitterest opponents to power has created. Bankruptcy in the money market, a general increase of crime, corruption of Legislatures, total want of confidence in our State representatives, all point to the calamity which, in the madness of a people’s rage, deprived Democracy of those powers which it had so intelligently and creditably executed.”

On October 21st, the Democrat announced:

Wall Street—The Crash. Yesterday was a fearful day in Wall street. The crash which many have anticipated for some days fell with terrible effect upon the city yesterday. No less than eighteen of our city banks suspended including some of the oldest and best banks in Wall street.

The Gazette’s editor that day seemed much more calm:

We notice by our exchanges that business is very dull everywhere, on account of the hard times. Flemington, we believe, is about as brisk as ever. Saturday last, our merchants had a big run all day, and all other branches of business seemed proportionately active. Hunterdon County Bank good as wheat.

But eventually, hard times caught up with Flemington. On Dec. 16, 1857, the Gazette’s editor wrote:

Considerable fault has been found relative to our Flemington markets. Farmers inform us that they bring their produce to our merchants and they refuse to comply with advertised terms. We shall hereafter give the prices they are willing to PAY (not sell for) or none at all.

A Moveable Bank

According to the official history of the Hunterdon County Bank,6 operations were begun in the basement of the James N. Reading mansion. (See “A Store, A Bank, A Mansion.”) The bank history states that

Records are not readily available on who was occupying the mansion when the bank was opened in two small basement rooms that had been used by Mr. Reading as his law offices. Entrance was gained to these quarters thru the areaway under the spacious front porch.

The authors of the pamphlet seem to have been aware that, by this time, James N. Reading had moved to Illinois. What they did not mention was that he left the mansion to his brother John G. Reading to dispose of, and, not succeeding at finding a buyer (it apparently being too grand for the real estate market), John G. himself moved in. So, it was merchant and very prosperous John G. Reading, one of the original bank commissioners, who allowed the bank to set up in his brother’s law offices.

The Bank history also commented on the vault in the Reading mansion:

Still preserved in the rear office is the masonry vault first used for the bank. Its interior was about four feet wide by five feet deep, and the arched ceiling was barely tall enough for the average man’s height.

Two iron doors secured the contents of this crude depository for the bank’s valuables, and a curious locking device was employed. To open the first door, it was necessary to raise a small trap door in the floor of the long drawing room upstairs. The bar securing the outer vault door could then be raised, giving access to the inner door, which was locked with a key.

It is a question whether the bank was still in that location in 1857, when a Trenton merchant advertised in the Hunterdon Gazette that he had “taken a room in Mr. Hugh Capner’s House, recently occupied by the Hunterdon County Bank, in Flemington.”

Mr. Capner’s house was further north on Main Street, at the corner of Main and Capner Streets. In 1860, Tunis Sergeant advertised for rent “the basement now occupied by him under the Hunterdon County Bank, for one or two years from the First of April next.”7 It wasn’t long before he found a tenant—John D. Hall. The Gazette’s editor reported that Hall,

formerly proprietor of the Union House, in this place, has just opened a Restaurant in the large rooms below the Hunterdon County Bank. [my emphasis] It is his intention to fit this place up in good style, so that an inside view will puzzle one to tell whether he is in Hall’s Saloon, in Flemington, or that famous establishment, Taylor’s Saloon, in New York.8

Having a “saloon” under a bank’s offices may not have been ideal. At some point later on, the bank moved to the building used by attorney George A. Allen, another one of the bank’s first commissioners and original investor in the Hunterdon Republican newspaper. That building was located a couple doors north of the office used by Alexander Wurts’ in 1851. On March 26, 1862, the Hunterdon Gazette published this note:

HUNTERDON DEMOCRAT. Our neighbor [Adam] Bellis has moved his office in a room over the Hunterdon County Bank, formerly the law office of Geo. A. Allen, Esq. [my emphasis] It is a handsome room in a handsome brick building, and no doubt neighbor Bellis feels quite proud, but we hope he will not put on airs on account thereof.

The bank history version goes:

How long the Hunterdon County bank operated at this site [the Reading Mansion] is not known definitely, but before 1864 its place of business was transferred to the north end of George A. Allen’s residence, where the Mutual store is now [1936] situated.

This two-story business building with a basement store adjoined the Allen residence, quartering his law offices, as was the custom. The bank occupied the first floor, reached by a long fight of steps, and vaults were built in the structure. On the top floor was the office and printing establishment of the “Hunterdon Republican.”

I suspect that the bank officers were not all that pleased with their new digs.

Hopewell Hall

also known as Flemington Masonic Hall

The Property

During the 1850s, John C. Hopewell had been instrumental in bringing Flemington into the modern era. (See “One Man Makes a Difference.”) He was involved in every aspect of the town’s improvements. He even tried serving on Flemington’s Town Committee. In that position, he helped to organize a fire company for Flemington. But governing probably did not suit him—he held office only one year, surrounded as he was by Democrats. After the American Party faded away, Hopewell and many others joined the new Republican Party.

Hopewell also went into the retail business in partnership with John S. Hockenbury, whose store was near or next to the Allen building, where the bank was located.

Although he was not ‘in at the beginning,’ by 1859, John C. Hopewell was one of the directors of the Hunterdon County Bank. As such he was aware of the insufficiency of the bank’s quarters.

On March 30, 1863, Hopewell bought a 1.13-acre lot in Flemington from the widow Caroline I. Sloan for $6,500.9 This was a pretty high price for the time and suggests there were buildings already on the lot. It was described as located on the east side of Main Street, bordering Anderson & Co., Spring St., John Hulse, Sarah Spencer, Joseph H. Higgins, and “J. R. & A. Hill.” (Anderson & Co. was a general store run by William Evans Anderson. John Robert Hill and brother Alexander Hill operated a tailor shop. Joseph H. Higgins ran a drug store.)

This property was probably adjacent to another one sold to Hopewell twenty years earlier, on July 19, 1844 by Caroline Sloan and her husband William H. Sloan for $1,350. It was a half-acre lot bordering Mahlon Fisher’s lot [today’s Doric House] and Spring Street.10 At least part of this property had originally belonged to early Flemington merchant Joseph P. Chamberlin (mentioned in “A Store, A Bank, A Mansion”).

The Building

We cannot know if Hopewell bought the Sloan lot in 1863 for the purpose of erecting a bank building on it or if he made that decision after making the purchase, but he seems to have begun construction of the building not long after the lot was purchased.

Unfortunately, we do not have notes or other records that describe how Hopewell came up with the design of his building. There is certainly nothing else like it in Flemington. And who did he hire to build it? There were plenty of carpenters in Hunterdon, although Mahlon Fisher was not among them as he had moved to Williamsport, PA.

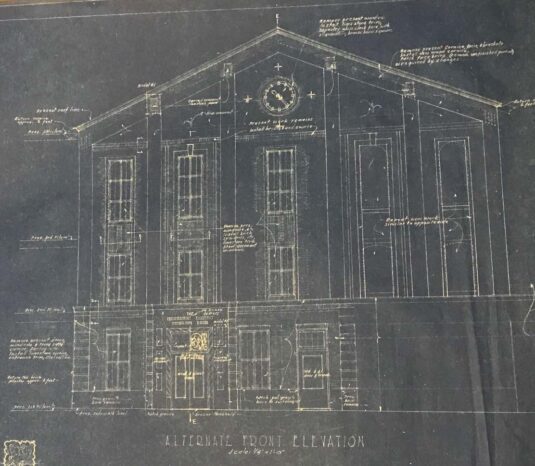

What we do have is a remarkable drawing made in 1936 when the bank was considering renovations.

What we do have is a remarkable drawing made in 1936 when the bank was considering renovations.

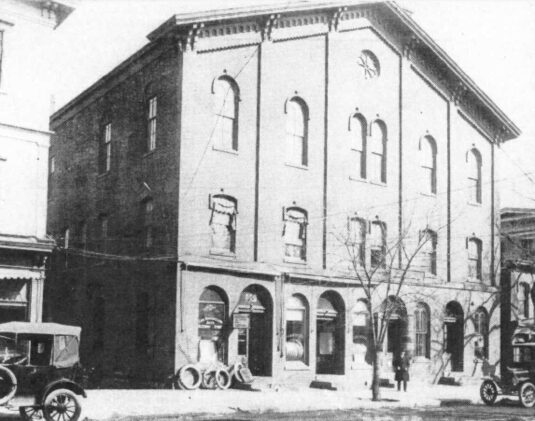

The ground floor doors and windows are changed from the original design, as can be seen in this view of the bank in 1902, when automobiles were just beginning to become popular, popular enough for one of the stores on the ground floor of the building to offer tires for sale.

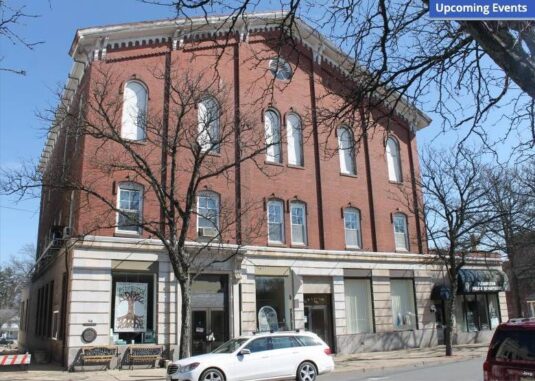

The building is very distinctive for its time and place. When it was built, in the years 1864 to 1866, it was unlike all the other buildings in Flemington, and probably in all of the county. There are those tall windows on the third story, and its distinctive roofline, resembling as it does the roof of a Greek temple. I pondered this awhile and then remembered that John C. Hopewell, the builder, spent many of his early years in the city of Philadelphia, a city that specializes in Greek Revival.

The building is very distinctive for its time and place. When it was built, in the years 1864 to 1866, it was unlike all the other buildings in Flemington, and probably in all of the county. There are those tall windows on the third story, and its distinctive roofline, resembling as it does the roof of a Greek temple. I pondered this awhile and then remembered that John C. Hopewell, the builder, spent many of his early years in the city of Philadelphia, a city that specializes in Greek Revival.

Modeled on Ford’s Theatre?

This claim, that the bank building was modeled on Ford’s Theatre, turns up in nearly every description of it. The bank’s own history (published in 1936) states so emphatically:

The front elevation of the large building erected by Mr. Hopewell was designed as a replica of the famous Ford Theatre in Washington, D.C., where President Lincoln was assassinated. Despite several alterations on the street level, the building today retains that original design.

But was it really? The theatre was undergoing renovations as the result of a fire in 1862 that had destroyed the previous renovations made by its owner, John T. Ford. He had purchased the abandoned building of the First Baptist Church in 1861 and set about turning it into a theatre. After the fire, Ford started over with new renovations that were for the most part completed by August 1863 when the theatre reopened.

However, a photograph taken shortly after the death of Abraham Lincoln in April 1865 shows that the cornice was not completed. (I chose this photograph to show the shape of the roof.) Compare that photo with a current one (below).11

Construction on Hopewell’s building in Flemington began after the theatre started its renovation, so there may very well be a connection. But Hopewell would have had to travel to Washington, D.C. to get a view of the building.

Chris Pickel, Flemington architect and expert on old buildings, has noted the similarities and the differences between Hopewell’s and Ford’s, and considers the resemblance a coincidence.12

As Chris observed, both buildings had “Two stories of brick above a smooth masonry arcade on the first floor, with a street-facing gabled roof. Five window bays across, with single arched windows separated by projecting vertical brick pilasters.”

However, Chris noted that despite the similarity of the roof line, the Hopewell building has its distinctive features: doubled central windows and round attic window, plus paired Italianate brackets along its gabled roofline.13

The Friends of Historic Flemington have reviewed the architecture of the building and made these observations (which can be found on their website):

Tradition says that 90 Main Street was modeled on Ford’s Theater in Washington D.C.; that building gained national infamy when President Lincoln was assassinated inside shortly after it opened in 1865. The similarity between the two buildings lies in their unusual rooflines; normally late nineteenth century Italiante buildings did not emphasize the slope of the roof, rather they were designed with bold horizontal cornices and relatively low sloped hipped roofs which cannot be seen clearly from below. Instead, this design features a boldly projecting and dramatically sloping cornice, which dominates the street below.

Over the years, there have been many tenants and owners of the building, and they usually left their stamp on it, but none more so than the Bank itself, especially in the 1920s when a new stone facing was added to the bank’s offices on the ground floor. Very little is left of the original interior details, except for ceiling trim on the third floor.14 And much of the interior architectural detail was removed during the renovations.

Now the bank belongs to a new owner who has his own plans for it. Those plans apparently take little cognizance of the building’s historic value. This short history is intended to make up for some of the building’s material losses.

There is more to say about the bank’s history as well as that of John C. Hopewell, which will be forthcoming in a future article. Also forthcoming, a history of the Reading store next to Union Hotel, which will also be saved in the future development.

Addendum

for the Fisher-Reading Mansion, June 9, 2021:

John G. and Sarah F. Reading remained in Flemington until 1870, when they moved to Philadelphia. Sarah Woodhull Reading died in Philadelphia on July 7, 1887 and John G. Reading died there on Jan. 27, 1891.

After having leaving Flemington, the Readings sold the Fisher Mansion to attorney John Newton Voorhees, Esq. of Readington Township for $12,000 (Deed Book 145 p.381). The mansion remained in the possession of Voorhees until after his death in 1897, age 61. (His portrait is included in Snell’s History of Hunterdon.) It was not until 1900 that his widow Hannah (nee Hannah Mary Large), and other heirs of John N. Voorhees, conveyed the property to George H. Large, Hannah’s brother. And there begins the long association of the Large family with the Reading Mansion.

Footnotes:

- This note was found on the website for Heritage Auctions. ↩

- I have not analyzed Rev. Janeway’s real estate investments, but in the 1850s he purchased several lots in Flemington. ↩

- Information about this chaotic period in the country’s history can be found in A Nation of Counterfeiters; Capitalists, Con Men, and the Making of the United States by Stephen Mihm, Harvard Univ. Press, 2007. Highly recommended. ↩

- HCHS, Capner Papers, Box 12, folder 624. ↩

- Nation of Counterfeiters. ↩

- “The Story of The Hunterdon County National Bank of Flemington; An Historical Sketch of the Institution and the Pioneers Whose Ideals Long Ago Placed ‘The Old Bank’ in a Position of Leadership in the Section It Has Served 85 Years,” 14 pp., reprinted from the Hunterdon County Democrat, Flemington, NJ, 1936. ↩

- Hunterdon Gazette, Jan. 4, 1860. ↩

- Hunterdon Gazette, Jan. 25, 1860. ↩

- H.C. Deed Book 128 p.169. ↩

- H.C. Deed Book 82 p.489. The Sloans had sold Mahlon Fisher his lot two years earlier. ↩

- Images of Ford’s Theatre found on www.fords.org. ↩

- Pickel was the one who saved those architectural drawings from 1936. He was quoted in an article that appeared in NJ.com in 2012 titled “Is Flemington-owned bank building a clone of Ford’s Theater?” I do not know the name of the article’s author. The 2012 article stated that the Hopewell building was erected in the 1880s. This is wrong. And much to my surprise, the Hunterdon Co. Master Plan’s “Sites of Historic Interest” claimed it was built in the early 1900s. ↩

- I want to thank Chris for helping me to understand the architecture of the building and for sharing his photo collection. As for the Italianate style, “Restoring Your Historic House” on Facebook explains: “The Italianate style arrived in the U.S. before the Civil War and took off after the war, with examples of the style appearing in all parts of the United States. ↩

- Many thanks to Mayor Betsey Driver for giving me a chance to visit the interior of the building and to construction superintendent Ken Kida for giving us a tour. ↩