Following the election of 1836, things got really interesting—so much so that I have devoted this post to only one year—1837.

The year began with great optimism in America. The economy was chugging along nicely (or so it seemed), a new president had been elected (Martin Van Buren), and all was right with the world. That optimism ended abruptly in March when the economy crashed, an event known as “The Panic of 1837.” That and political developments in New Jersey kept the editor of the Hunterdon Gazette quite busy.

A New Approach for the Gazette

By 1837, the Hunterdon Gazette had matured, becoming the essential newspaper for the county. All important notices were published there. In 1837 the editor, Charles George, modified his editorial policies to provide more information on local government, most likely as a response to the campaign of 1836. He began publishing news of bills pending before the state legislature and allowed many more “communications” from supporters of both political parties. In April, he published the results of town meetings throughout the county, with the names of men (and only men) elected to various town positions, i.e., town clerk, assessor, collector, judge of elections, freeholders (each town got two), town committee members (five), commissioners of appeals (2), constables (4), pound keeper, overseers of the poor (4) and later on, commissioners of deeds. He would continue this practice every year. If only he had done this from the beginning (in 1825); still, as a researcher I am grateful for this.

The Panic of 1837

In 1833, when Alexis de Tocqueville visited America, the country was “prosperous, contented and boastful.”1 But that appearance turned out to be short-lived. Andrew Jackson’s abhorrence of the banks, especially the national bank run by Nicholas Biddle, led him to issue the ”Specie Circular” in 1836. This was one of his last acts as president. It required that payments for government land be made in gold or silver (specie), rather than the paper money that had been proliferating from all the new banks that had been created during the land boom. The west had opened up, and settlers were financing their land purchases through banks whose loans were not properly secured. Unfortunately, Jackson’s cure, the Specie Act, was worse than the illness.

Part of the reason people had felt so prosperous in the early 1830s was that credit was too easy. And there was so much to spend it on, in particular, internal improvements and public lands in the west. The demand for new railroads and canals throughout the country was huge. It certainly was in New Jersey, which saw the opening of the Delaware & Raritan Canal in 1834. The opening of the western lands had prompted a massive exodus of families from worn-out farming areas in the east. But speculators, being much better informed about the best locations, were able to buy up lands before the settlers could, forcing them to purchase at inflated prices. Meanwhile, states that were financing the roads, canals and railroads did so without worrying too much about how they paid the bills.

Between 1830 and 1836, there were 347 new banks chartered.2 Many of them were not sitting on solid foundations, as the founders and their depositors would learn to their cost. In January 1837, Charles George observed that “The applications for new banks seem to increase rapidly.” He thought that “two or three, out of the whole number applied for [in New Jersey], will probably be granted.”3

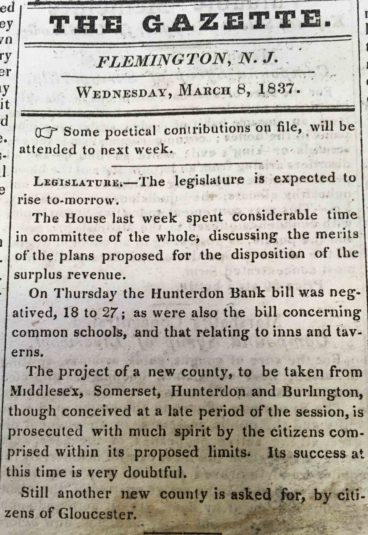

Two bank applications this year were defeated, one for a new bank at Lambertville and another called “The Hunterdon County Bank.” George reported on March 8th that “On Thursday the Hunterdon Bank bill was negatived, 18 to 27.” I do not have details on where this bank was meant to be located (Trenton or Flemington?), or why the application was denied.

Two bank applications this year were defeated, one for a new bank at Lambertville and another called “The Hunterdon County Bank.” George reported on March 8th that “On Thursday the Hunterdon Bank bill was negatived, 18 to 27.” I do not have details on where this bank was meant to be located (Trenton or Flemington?), or why the application was denied.

The Surplus Revenue

Another factor that contributed to the false sense of prosperity was the surplus that was generated from the sale of public lands, commonly referred to in the newspapers as “The Surplus Revenue.” This allowed Jackson to pay off the national debt and still leave millions left over to be returned to the states. Over a million dollars went to New Jersey alone. Technically, these were loans, but everyone knew that the money would never be repaid.

The big question was how to spend this windfall. The Gazette reported on a meeting held in Readington on January 20th, “to take into consideration measures to be recommended to the legislature for the disposition of that part of the surplus revenue of the United States apportioned to this state.” Their resolution asked the Legislature to apportion the fund among the township committees of the state, “to be loaned out by the said committees on bond and mortgage or other permanent security, and the interest to be appropriated solely for the benefit of common schools.”4 But that’s not what happened. Instead, the money went to the county freeholders for them to disperse. A notice was published in the Gazette on March 29th, to the effect that a meeting would be held by the freeholders at the Courthouse on April 4th “to devise plans for disposing of our share of the surplus money.” The freeholders determined to distribute the funds to the townships based on the amount of taxes each one paid. Amwell was the big winner, getting a total of $13,619.94. Ewing Township got the smallest amount: $1,953.92.5

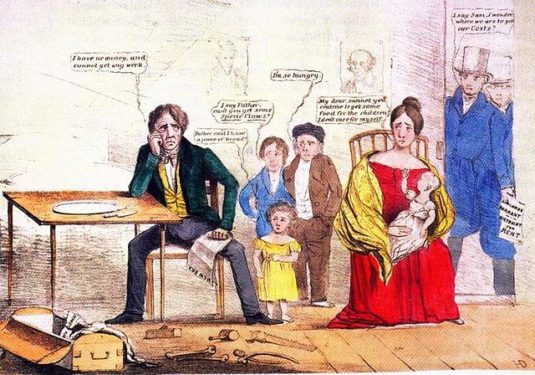

This infusion of funds was undoubtedly appreciated by those anxious to improve the school system. But it did little to help the local economy. Bank loans were way out of proportion to the hard currency on hand, sometimes by as high a factor of 20 to 1.6 Inevitably, creditors began calling in their loans, causing prices to collapse. The value of paper money declined rapidly. The first indication of economic trouble appearing in the Gazette was on March 29, 1837, with news of “The Money Market.”

The effects of the pressure which has existed in the money market for some months past, are beginning to be seen and felt in a manner that will produce a sensation throughout the country. The intelligence of a heavy failure in New Orleans involving credits to the amount of twelve millions, is given below. We learn that on the receipt of the news in New York last week, an extensive exchange broker of that city failed; –and the failure of many others is believed to be inevitable. Good paper commands 3 per cent. per month; Flour has fallen, and sales dull. A further decline in price is expected–consumers purchasing what is needed from day to day, in anticipation of its being lower.

In early April, the Gazette reported (optimistically) that banks were taking measures to shore up the economy.

It will be seen that the Bank of the United States has promptly responded to the wishes of the merchants, by uniting with the city banks in affording relief to the foreign and domestic exchanges of the country. This, with the increase of discounts, will tend speedily to restore the business of the country to a solid basis.7

But future editorials were not so encouraging. By late April things were getting desperate. George wrote:

A large meeting of merchants without distinction of party was held in New York last week to take into consideration the existing depressed state of business in the country. A numerous committee was appointed to proceed to Washington, to remonstrate with the Executive [Pres. Van Buren] against the continuance of the Specie circular, and to urge its immediate repeal; to ask that payment of bonds held by government for duties shall not be exacted until after the first of January next; and to urge upon the President the propriety of calling an extra session of Congress, to devise remedies for the alarming embarrassments of the country. . . A southern paper says: “The planters of the southwest are in a very desperate condition, from the late depreciation in the cotton value. The amount of responsibilities assumed under the impression of the stability of the past year’s price is enormous.”8

The effects of the Panic were making supporters of Jackson’s and Van Buren’s administrations disillusioned. In Hunterdon the focus of political opposition was known as “the caucus system,” which was still employed by the Jackson party, even though it should have been dropped when the party began having party conventions. Charles George departed from his previous practices by publishing a long letter from a writer opposed to the caucus system. This was, in fact, the position taken by the party out of power, the Whigs, whose policies George sympathized with. This is probably the first hint of the Gazette’s political leanings. There would be many stories to follow highlighting the faults of the caucus system.

As the economy worsened and banks tottered on the brink, or in some cases fell over, a drastic step was taken. In May the banks suspended specie payments. For the time being, no one could get any gold or silver out of the banks.

A note here—On June 20, 1837, King William IV of Great Britain died without any legitimate children (all ten of his children were illegitimate), so he was succeeded by his niece, Victoria, who was only 18 years old at the time.

The Effect of the Panic in Hunterdon

Many parts of the country experienced considerable hardship thanks to the crash. But Hunterdon seems to have escaped the worst of it. I expected to see many notices of bankruptcies and debtors taken to court, but there weren’t all that many more than usual in the pages of the Gazette. In fact, one location in the county was thriving, according to this from the Gazette of June 21, 1837:

COMMUNICATION. Some of our towns, so admirably situated for business, where the blighting influence of Speculation has not been felt, and the energies of her people dampened, must continue to grow and prosper.—The great business advantages of Lambertville are too apparent to be overlooked; and we are pleased to notice an improvement now going on in that thriving village by individual enterprize[sic].

A new foundry and machine shop was being established along the canal by “Messrs. Cooch & Moon, machinists of New Hope” who would “employ a large number of workmen.” And on June 28th, Jacob B. Smith, blacksmith, advertised that he had just opened a shop on Bridge Street in Lambertville for “the Tin Making Business.” Smith also specialized in mending and repairing of “Tin Ware, Brass and copper Kettles, done at the shortest notice, and the highest prices paid in trade for old Pewter, Copper, Brass, and old Iron Castings. He also makes and furnishes sheet iron Stoves, Stove Pipe, Boilers, Dripping-Pans, &c. &c.”

When times got tough, the most vulnerable were the first to suffer, as can be seen from this letter published in the July 26th issue on the subject of “Emigrants.” (Interestingly, the writer uses the word emigrants to designate people we now identify as immigrants.)

For the Gazette. A writer in the Gazette is endeavoring to make out that the people of this country have suffered by the emigration of foreigners. This is not the fact; without them, our great works of internal improvements, &c. would never have been accomplished; it was soon discovered while business was brisk in the country, and during the continuance of trade and improvements, that foreign laborers were necessary, if not indispensable, and every encouragement was given to their emigration to this country, because their services were wanted. They have been instrumental in effecting much, and the prosperity of our country is attributable in a great measure to foreign emigrants. Now that trade is depressed and business dull, and our public works in many cases have stopped, it is desirable that emigration should stop with them, because our cities now find it difficult to support their own population!

We can inform the writer of that communication, that the evil of which he speaks will correct itself, and emigration will cease when they can find no employment or means of settling themselves comfortably.

The Fall Conventions and the 1837 Election

Resolutions passed at the Whig (anti-caucus) convention held on September 23rd reinforced this tolerant approach. The party branded itself the “Hunterdon County Democratic Convention,” which is certainly confusing. One of the resolutions at this convention (No. 11) mentioned that “those opposed to bank monopoly and Caucus corruption, have no hired press or newspaper at their command” unlike the Jacksonians who had the Trenton Emporium to speak for them. I suppose they did not consider the Hunterdon Gazette to be their mouthpiece, which was just what Charles George intended.

Interestingly, these anti-Jacksonians declared that the Surplus Revenue was aimed at “crushing the Anti-Caucus democrats of Hunterdon, and strengthening the hands of the bank and monopoly leaders.” Politicians always benefit from having money to hand out.

Despite their best efforts, the Anti-Caucus party did not succeed in ousting the Jacksonians in the fall elections. But they came closer than ever before. George observed that

The Caucus Ticket succeeded in this county by a small majority, with one exception. Mr. Huffman, a Whig, has a majority of five votes over Mr. Servis, and of course is elected.–The majority in Hunterdon is too small to be considered as deciding the questions which divide the parties–they doubtless try it again next year.9

This small win in Hunterdon County was enough for “the Whigs of Trenton” to have a celebration. In the next issue (Oct. 25th), George reported:

On Wednesday of last week, the Whigs of Trenton fired a salute of one hundred guns, and partook of a cold collation in honor of their recent success at the polls in this State.

Philemon Dickerson was governor from the fall of 1836 to the fall of 1837. He was a committed Jacksonian, but his brief tenure as governor was frustrating. During his time in office, the Whigs controlled the Council (state senate), but not the Assembly, and prevented the annual joint meeting from taking place. This meant that appointments to local and state offices were not made. The public blamed the Democrats, who lost the fall election to the Whigs.10

Official returns for state legislature, sheriffs and coroners were reported in the Gazette on October 18th. The legislature convened October 24th for their joint meeting to elect a new governor and other state officers, judges, justices, commissioners and members of the Hunterdon Brigade.11 Gov. Dickerson, who had tried unsuccessfully to make the banks resume specie payment, was replaced by William Pennington, a confirmed Whig.

Another troubling item was the law passed by the legislature to prohibit banks from issuing bills smaller than five dollars. This was considered a hardship for the little guy, and on December 6, 1837, the Gazette reported a public meeting took place in Lebanon Township by those people hoping to petition the legislature to repeal that bill. One of their resolutions stated that “we think the banks of this state have been unusually prudent throughout the whole of the present monied [sic] derangement, and are at this time deserving of every confidence from the people, and that the suspension of specie payments by the banks of New Jersey has been a matter of necessity, not of choice.” They also

Resolved, That the present extraordinary state of things demands another course of legislation, and that we recommend to the members of the legislature from the county of Hunterdon to support the suspension of the act preventing the issue of small notes, for such a period as the legislature in their discretion may deem proper.

On November 1st, a dinner was held “at the house of N. G. Mattison in Flemington,” to celebrate the “recent election . . . against the corruption of the Caucus.”12 As was the usual practice, several toasts were given, and the Gazette published them all, including these:

The Anti-Caucus democrats of Hunterdon—too honest to do wrong, and too intelligent to be deceived.

The office-holders’ fund at Washington, for buying votes—it cannot buy New Jersey.

[To] The State Election—Though the Caucus men had the “yellow boys shining through their silken purses”—yet with nothing but the sling and the stone we have laid the proud Goliah [sic] low.13

As the year approached its close, Charles George took note of the fact that “The present number [published on Nov. 29, 1837] completes the fifth volume of the Gazette, new series,” but he said nothing about how well the paper was doing. In the next paper, published on Dec. 6, 1837, George commented on a new development that had been gaining ground during the past year:

New County.—One of the first objects that will claim the attention of the legislature at the adjourned sitting, is the project of a new county, proposed to be formed out of the townships of Nottingham in Burlington county, East and West Windsor in Middlesex, Montgomery in Somerset, and Hopewell, Lawrence, Ewing and Trenton in Hunterdon. Measures have already been started to obtain the sense of the people in those townships on the subject ; and a convention of delegates to represent them is to assemble in Trenton on the 20th inst. to determine the limits of the new county, and adopt measures to secure the passage of a law creating it.

To the people of the county of Hunterdon this is an important matter. Are we prepared to part with the large and influential section of the county proposed to be cut off from us ? If we are, our silence will be construed into acquiescence. If not, let us speak out, that we may be heard.

One could argue that the year 1837 ended in a whimper, as the economy was nowhere near recovery, but this announcement that a new county was being seriously considered came as something of a bang.14 1838 turned out to be another significant year for Hunterdon County and for the Hunterdon Gazette, as will appear in the next article in this series.

Postscript (April 7, 2017):

I had neglected to check Snell’s History of Hunterdon when writing this article on Charles George. There were a couple interesting items there. For instance, in 1828, a Committee was named to consider “the question of turnpiking the streets and improving the sidewalks” of Flemington. The members were Charles Bonnell, Samuel Hill, Neal Hart, Charles George and E. R. Johnson.15 And in 1830, the first Sunday School was established in Flemington, and Charles George was chosen to be its first superintendent.16

Footnotes:

- Reginald Charles McGrane, The Panic of 1837; Some Financial Problems of the Jacksonian Era, 1924, 1965. ↩

- McCrea, p. 13. ↩

- Hunterdon Gazette, Jan. 25, 1837. ↩

- Hunterdon Gazette, Feb. 1, 1837. ↩

- Hunterdon Gazette, April 12, 1837. ↩

- McCrea, p. 16. ↩

- Hunterdon Gazette, April 5, 1837. It should be noted that the Bank of the United States was no longer a national bank, but continued to operate as a state bank, without changing its name. ↩

- Hunterdon Gazette, May 3, 1837. ↩

- Hunterdon Gazette, Oct. 18, 1837. ↩

- Birkner, Linky and Mickulas, The Governors of New Jersey, Biographical Essays, p. 141-44. This book is highly recommended. ↩

- Hunterdon Gazette, Nov. 1, 1837. ↩

- Hunterdon Gazette, Nov 8, 1837. ↩

- This expression—yellow boys and silken purses—is not familiar to me. Perhaps some history buffs can explain it. ↩

- I have previously written about the creation of Hunterdon County in 1838 in “The Division of Amwell Township, 1838.” ↩

- Snell’s History of Hunterdon, p. 331. ↩

- Snell, p. 319. ↩

Marfy Goodspeed

March 26, 2017 @ 3:02 pm

In response to my query about this expression–“Though the Caucus men had the “yellow boys shining through their silken purses”—an anonymous correspondent has put forth a very likely explanation. The yellow boys were gold pieces shining through the silk purses of Jacksonian operatives who were ready to provide bribes where needed. Makes sense.