This is a continuation of the saga of the Hunterdon Gazette and its first owner and editor, Charles George. Please refer to Charles George & the Hunterdon Gazette, part one and part two, and 1837 in Hunterdon County.

The country recovered from the Panic of 1837, but politics remained as contentious as ever. Charles George left the paper in 1838. The new editor was a more outspoken supporter of the Whigs. The paper was published all through the Civil War, but after the war ended it was taken over by a fervent Democrat who merged the Gazette with the Hunterdon County Democrat. By that time, Republican readers had a new paper to rely on, the Hunterdon Republican, which began publishing in 1859, carrying on a rivalry with the Democrat that lasted until 1953.1

Recovering From the Panic

By 1838, things appeared to be improving. Banks were again accepting “small bills” and some of them resumed specie payments by April. Here are a couple notices from the editor of the Gazette pertaining to the banks:

May 2, 1838: “Resumption. –The Banks in New York and Boston are already paying specie for their small bills; and specie can be had at their counters in any reasonable quantities . . . The premium on specie having ceased, many who have held it are depositing it in the banks.”

May 30, 1838: “Tickets. –The days of Shinplaster currency2 are nearly numbered — change tickets are rapidly disappearing from circulation, and specie is taking their place; and none will regret the change. The necessity for tickets under one dollar has ceased, as the banks generally pay specie for all sums under that amount.”

Despite this improvement, times were still challenging, especially for store-keepers who relied on the ability of customers to pay their bills. In 1838, the Gazette published quite a few notices of stores that went out of business and store locations for rent. Isaac G. Farlee, who will appear later in this article, was one of those giving notice that his “Store Stand” in White House was for rent.3 The Gazette also published warnings not to accept notes from various people who were found to be unreliable, if not dishonest.

Political Divisions, March 1838

Thanks to the rise of the Whig party, in March 1838 a new county and three new towns were created in New Jersey. Hunterdon lost its southern half to the new county of Mercer, which also included parts of Somerset, Middlesex and Burlington. All townships north of Hopewell remained in Hunterdon. A year before, the Gazette had reported that the project of creating a new county “had been prosecuted with much spirit by the citizens comprised within the proposed limits.” But the editor’s opinion, that “Its success at this time is very doubtful,” proved to be in error. The project did succeed, thanks to the votes of Joseph Moore, a Democrat living in the Whig township of Hopewell.4

The bill become law in February 1838 and took effect the first Monday in April. At the same time, the legislature, again thanks to the vote of Joseph Moore, divided Amwell into three new towns, so that Flemington was now considered part of Raritan Township, rather than old Amwell. Outrage about this was expressed in long letters to the Gazette which also published descriptions of the several public meetings of protest that took place.

The Gazette Changes Hands

In July 1838 Charles George finally gave up the Gazette for good. In the issue for July 11, 1838, he printed this announcement:

TO THE PUBLIC. The subscriber [George] has disposed of the establishment of “The Hunterdon Gazette,” to Mr. John S. Brown; in whose name the paper will in future be issued, as editor and proprietor. Mr. Brown is from Bucks county, Pa.; is a practical Printer, and is believed to posses the requisite qualifications for making the paper useful and agreeable.

The subscriber respectfully solicits for his successor, a continuance of the patronage he has received during a period of thirteen years labor and toil in this place.

John S. Brown introduced himself in the next issue, on July 18, 1838:

TO OUR PATRONS. The readers of the Gazette are already informed that Mr. [Charles] George, who has so long and faithfully served them with the weekly news, has relinquished the proprietorship of the paper, and consigned it to other hands. – Whether it will be conducted with the same good feeling, the same respect, and the same punctuality, remains for us to show. One thing our subscribers may be assured of, that our entire time, diligence, and attention, will be devoted to their gratification, amusement, and instruction.

We propose to offer to the public, a paper which will combine, with the news and politics of the day, the latest agricultural, literary, and scientific intelligence. We feel desirous of giving it the character of a good family paper – one that can be read with pleasure, not only by the male portion of the family, but will give gratification and instruction to the female and younger members also – one calculated to interest all ages.

It will most naturally be enquired, what will be the politics of the Gazette! Upon this subject, we shall take a firm, decided, but moderate stand; and endeavor to support it with manliness, dignity, and fearlessness. We confess to be a Democrat – an old-fashioned Democrat – and to hold the pure Democratic doctrine of our fathers – of such men as JEFFERSON and PATRICK HENRY. We confess to follow no man’s man; but to be an independent Democratic Republican – who believes in the will of the people, as expressed through their lawful representatives. We shall give our political faith in the very words of these great men: –

He went on from there at some length. When he claimed to be “an old-fashioned Democrat,” what he actually meant was that he supported the Whigs and opposed the Van Buren administration. Brown was far more politically outspoken than Charles George had been. And political feeling was fairly intense in the summer of 1838. In the issue of August 15, 1838, Brown wrote,

We feel constrained to tender our sincere thanks to those who have so liberally come forth to our aid, since our commencement in business, and especially during the last week. It is great cause for encouragement ; and far exceeds our most sanguine anticipations. Notwithstanding the untiring efforts made against us, our subscription list has increased, and is still growing better. We do not state this fact, by way of boasting, nor for effect, but simply to show that the citizens of Hunterdon are not devoid of that spirit of liberality which characterizes true republicans—men who are determined to think and act for themselves, and support those who do the same.

We hope our friends will not relax their exertions—remember who and what we have to contend against—let untiring industry and perseverance be our motto.

So it seems that all George’s efforts to maintain a position of neutrality for his newspaper were set aside, but then his approach had been unusual for the time. In the 19th century, newspapers all over the country were very clear about their support for one political party or another. And so it was to be for the Gazette.

The willingness of the new editor to be more outspoken about his political preferences helped to trigger the establishment of a second newspaper in Flemington, one designed to counter-balance the politics espoused in the Gazette. This was the Hunterdon County Democrat, founded by George Clinton Seymour. Its first issue was published on September 5, 1838. From that point on, up until the Gazette folded in 1866, the two newspapers kept up an energetic rivalry.

During the days when Brown was editor, the newspaper business was just as arduous as it had always been, what with typesetting and operating a hand press. Like Charles George before him, John S. Brown relied on the help of a teenager to get his paper published. On July 25, 1838, he published this notice:

WANTED IMMEDIATELY – An Apprentice to the Printing business – a smart active lad, of industrious habits and good moral character – from 14 to 16 years of age. Apply at this [the Gazette’s] office.

Consistent with Brown’s political leanings, and perhaps as a way to supplement his meager income, he was given a political job by the powers that be. He became the Postmaster of Flemington on June 21, 1841. But he didn’t keep the job very long. On October 26, 1841 he was replaced by another Whig, George W. Risler of Readington. Why Brown was replaced with someone of his own party is something of a mystery. Risler was a partner with Isaac G. Farley under the name Farlee, Risler & Co. in the management of a store in Whitehouse, probably in that very store Farlee had previously advertised. Farlee was an influential Hunterdon Democrat who had served as County Clerk from 1830 to 1840 and was later elected to Congress. Which makes me wonder, was Farlee responsible for Risler’s appointment? If so, could it be that personal loyalty was more important to Farlee than political loyalty? Or that George W. Risler was not that strong a Whig? Questions I cannot answer at this time without some serious research into Farlee’s life (which would probably be very interesting).

What Happened to Charles George?

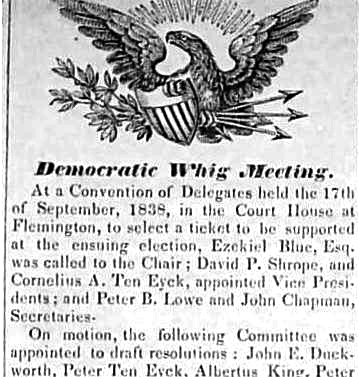

Charles George was a man of high principals. Not only was he a leader in the temperance movement in Hunterdon, he also served as a deacon of the First Baptist Church in Flemington. He had gained a reputation as an upstanding fellow, which made him just the sort of person to run for political office. On September 5, 1838 (the same day as the first issue of the Democrat), George’s name appeared on a list published in the Gazette of nominees for the New Jersey Council (the State Senate).5 On September 19th the Gazette published the results of the “Democratic-Whig Meeting” held at the Courthouse in Flemington, at which Charles George was chosen to be the party’s candidate for Council. On October 3rd, the Gazette briefly noted that George’s opponent for Council on the “Van Buren Ticket” would be Joseph Moore, the person responsible for the division of Hunterdon County and Amwell Township earlier in the year.

Charles George was a man of high principals. Not only was he a leader in the temperance movement in Hunterdon, he also served as a deacon of the First Baptist Church in Flemington. He had gained a reputation as an upstanding fellow, which made him just the sort of person to run for political office. On September 5, 1838 (the same day as the first issue of the Democrat), George’s name appeared on a list published in the Gazette of nominees for the New Jersey Council (the State Senate).5 On September 19th the Gazette published the results of the “Democratic-Whig Meeting” held at the Courthouse in Flemington, at which Charles George was chosen to be the party’s candidate for Council. On October 3rd, the Gazette briefly noted that George’s opponent for Council on the “Van Buren Ticket” would be Joseph Moore, the person responsible for the division of Hunterdon County and Amwell Township earlier in the year.

He did take the election very seriously, writing in October 3d edition that “The election which is to take place next week, is, perhaps, one of the most important that has ever occurred in the State of New Jersey.” He went on to explain how Congressional and State offices would be decided on the same day (previously they had been on different days), and that members of Congress would be deciding “either for or against the sub-Treasury, and the leading measures of the General [Van Buren] Administration.” Also, that the members of the N.J. Council would be choosing who the next U. S. Senator would be, since Samuel L. Southard would be retiring the following March. And yet, despite his concern over the outcome of the election, he never mentioned the name of Charles George, the Whig candidate for Governor’s Council. But then, he did not choose anyone else to endorse either, so perhaps this was not yet common practice.

Election results were published on October 17, 1838. The Congressional election was at the top of the ticket followed by the Governor’s Council, and the winner was Joseph Moore. George won Amwell (which included Flemington) and Moore’s hometown of Hopewell (which supported the Whigs), but Moore won all the other towns with a total of 2578 votes compared to George’s 1664.

Election results were published on October 17, 1838. The Congressional election was at the top of the ticket followed by the Governor’s Council, and the winner was Joseph Moore. George won Amwell (which included Flemington) and Moore’s hometown of Hopewell (which supported the Whigs), but Moore won all the other towns with a total of 2578 votes compared to George’s 1664.

This loss probably convinced Charles George that he no longer had a future in Flemington. On March 19, 1839, this notice appeared in the Gazette:

“The subscriber intending to remove from Flemington in the course of the spring, earnestly requests all persons still indebted to him for Printing and subscription to make immediate payment.”

Soon afterwards he and his wife moved back to their home town of Philadelphia. Even though he moved away, Charles George did not sell his house in Flemington. In an ironic twist, he rented it to George Seymour, editor of the Hunterdon County Democrat. According to Hubert Schmidt (from letters on file at the Rutgers Library), George had a very hard time selling the house, and nearly as hard a time collecting rent from his tenant, which amounted to only $80 per year. George advertised the lot for sale on December 17, 1839, it being “directly opposite the Methodist Meeting House.” The sale was to take place at the Inn of Mahlon Hart at 2 p.m. on the 28th, a Saturday. But apparently, it did not sell. The advertisement gave a nice description of the house, though:

The dwelling house is two stories high, with a lobby, kitchen, cistern-house and wood-house adjoining; a barn and hog pen, a garden enclosed, and the Lot enclosed with new fence. The location is central, and eligible for business, or a private residence.

In the 1840 census, George was counted in the New Market ward of Philadelphia, when he and his wife were said to be between the ages of 24 and 35, with a male child less than ten years old. Two of his children were not counted—daughter Lucretia, age 18, and son Samuel, 13, as they had both died in Philadelphia in 1840, Lucretia in June and Samuel in December. (Apparently Samuel was not living with the family when the census of 1840 was taken).

In 1850, the Philadelphia census showed that George was employed as a printer, age 55. Living with him and his wife Mary, age 52, were four of their children. (The ages given in the 1840 census must have been incorrect.) What is odd is that the census states that all the George children were born in Pennsylvania, including those born in 1825, 1826 and 1833, when the family was living in Flemington. Also in the household were nine others who were unrelated, some of them being domestics. The George family probably needed the extra funds that came from running a boarding house, along with whatever income they could get by renting the house in Flemington.

Charles George died two years after the 1850 census, on March 25, 1852 at the age of 57, and was buried in the Mount Moriah Cemetery in Philadelphia. To my surprise, his death went mostly unremarked. I found only one newspaper that published an obituary for him—the Trenton State Gazette (a Republican paper). It read:

Charles George, Esq., the founder of the Hunterdon Gazette, and the publisher and editor of that paper for a number of years, died in Philadelphia last week. He gave the paper a character of much respectability, and as a man was greatly esteemed.”6

Probably the explanation for why newspapers in Flemington had not acknowledged his parting was bad timing. The local newspaper most likely to publish an obituary for George was the Hunterdon Republican. But its first issue did not come out until 1856, four years after George’s death. As for the Gazette, there may have been an obituary published, but the issues between March 17 and April 12, 1852 are missing from the collection at the Hunterdon Co. Historical Society. And apparently the editor of the Hunterdon County Democrat was indifferent to George’s history in Flemington.7

In December, 1856, Mary George, a widow, offered to sell the Flemington lot at a public sale to be held on January 20, 1857. Her advertisement stated that John Volk was residing there, opposite the Methodist Meeting House, and that it was “a very desirable property.” Those interested were advised to contact B. [Bennet] Vansyckel in Flemington or Silas A. George, Esq. (her son) in Philadelphia.8

The 1860 census for Philadelphia shows that Mrs. George was still operating a boarding house, but by 1870 she had moved in with her daughter Maria and son-in-law John P. Blackwell in Mt. Pleasant, Westchester County, NY. She died there on April 16, 1878, at the age of 84. Unlike her husband, Mary George did get an obituary in the Hunterdon County Democrat. It was published on April 30, 1878:

Died, April 16, 1878, at Tarrytown, N.Y., Mrs. Mary W. George, widow of Mr. Charles George, for many years deacon of the First Baptist Church in this city [Flemington]. She was born May 3, 1793 and with her afterwards husband was baptized in 1817 by Rev. Dr. Holcombe, in the Schuylkill River.

We take the above from the National Baptist, Philadelphia, of a recent date. Mrs. George will be remembered by many of the older residents of Flemington, as the widow of Charles George, the founder of the old Hunterdon Gazette, March 24th, 1825.9

The Demise of the Hunterdon Gazette

Despite losing his position as Postmaster of Flemington, John S. Brown hung on as editor of the Gazette for two more years, but by March 1843, he had had enough and sold the paper to John R. Swallow.

Brown published his “Valedictory” on March 1, 1843. As one might expect, he took some pride in his management of the paper.

In severing my connection with this paper, I have been controlled by considerations which more or less influence all men in their progress through life—those, as they believe, which bear propitiously upon their prospects for the future; and it is a consolation that will ever sustain me, in whatever sphere I may be engaged, that here, where my first and youthful efforts have been expended in political life, and where they have been uninterruptedly continued for a period of nearly five years, nothing untoward has occurred to mar, in the least degree, the harmony of that party who have more especially extended to me their support; and that of my political opponents, and especially in our personal intercourse, my memory can cherish nothing but their courtesy and kindness. . . .

This paper now passes into other and abler hands. The great principles that have heretofore controlled it, will still direct its movements; and it again appeals to the Whigs of the county for its support. A great battle is before us. The contest of 1844 involves all that is dear to the country. For years we have been retrograding; and it is now a problem whether we have yet reached the lowest point of depression. The true and only remedy for this is to be found in the success of the principles which constitute the basis of the creed of the great Whig party of the Union, to wit:

1. A sound and uniform currency.

2. Protection to home industry and domestic manufactures, and a consequent enhancement of the agricultural interest of the country.

3. One Presidential term.

4. A diminution of the power and patronage of the President.

5. A restriction of the Veto power. . . . if there does exist a greater desire to be informed of the great questions which are now agitating the public mind—if our community embraces a greater number of readers than formerly—and if the Whig party of the county are arming themselves with the weapons of reason and truth for the great conflict of ‘44—all of which I believe—I think that my successors have before them a larger and more fruitful field in which to harvest where I have only gleaned.

As for the new editor and owner, Brown had this to say:

Mr. John R. Swallow, a young man personally and favorably known to a large number of the people of this county, its [the paper’s] future publication, and the management of all the business connected with the office, devolve upon him from this date. He will be aided in conducting the paper, by Mr. Henry C. Buffington, a gentleman who has before been connected with the Whig press of New Jersey. They are well qualified for their station; and we should deem it a slander upon friends of the paper, to express even a suspicion that their labors will not meet an adequate reward. Next week they will speak for themselves.

Swallow did not last long. In early 1844, he sold the paper to Henry C. Buffington. The years between 1843 and 1863 were challenging ones for the newspaper business. Both the Gazette and the Democrat tended to ignore local news in favor of national and international news, which they could crib from other sources. Perhaps their papers might have thrived better if they had given more attention to the world just outside their office doors. Hubert G. Schmidt does a good job of describing this period, which I will skim over. His history of the press in Hunterdon is strongly recommended.10

In 1854, Buffington sold the Gazette to Willard Nichols, who unwisely chose to support the American (Know-Nothing) Party in 1856. This did not go over well and by 1858, the paper was bankrupt and offered at a sheriff’s sale. The purchaser was Alexander Suydam, who continued to support the American Party.11 As it turned out, Nichols, and Suydam after him, would have been much better off if they had transferred their support to the newly-formed Republican Party (created in 1854). Two years later, a new paper appeared—the Hunterdon Republican. Its editor, Thomas E. Bartow, was far more able than Suydam was and his paper basically displaced the Gazette, which struggled along until the Civil War had ended.

Note: Since first publishing this article, I have covered more of Willard Nichols’ tenure at the Gazette. See Political Turmoil and Choosing Sides; also A Store, A Bank, A Mansion.

In 1863, the Gazette was purchased by J. Rhutsen Schenk,12 who proved to be a much better editor than those who preceded him; Schmidt called him a “live-wire.” Despite his abilities, when the Civil War came to an end, the Hunterdon Gazette did also. At first this seems odd—after all, as Hubert Schmidt wrote, the war years “had been a period replete with news and apparently more Hunterdon County people had acquired the newspaper habit than ever before.” During that time, the Gazette had forged ahead of the Democrat because of the Gazette’s ability to provide local news, while the Democrat was run down and its editor, Adam Bellis had not kept up with the times. In 1866, Charles Tomlinson attempted to buy the Democrat, but Bellis refused to give it up. So Tomlinson turned to the Gazette.

As it happens, editor and publisher J. Rhutsen Schenk was ready to give up ownership of the paper. He had served in the Union Army for nine months in 1863, before taking over the job of editor of the Gazette in September of that year. Unlike the Hunterdon Republican which strongly supported Lincoln’s war measures, the Gazette under Schenk was somewhat less fervent. This prompted much unjustified criticism of Schenk; he was called a copperhead and accused of carrying “the taint of a traitor about his clothes and was a secessionist at heart” (this we learn from his parting editorial). He wrote that his opponents did what they could to discourage his subscribers and that those who had been maligning him were actually his friends and “leading republicans.” The people who had cancelled their subscriptions soon returned to the paper, with the result that

the Gazette, has attracted more attention, and has been more in demand than any other paper in the place. We have labored, and labored constantly, unceasingly, in all departments of the business, and so far as we know satisfaction has been guaranteed.

When Flemington was a mere hamlet, it [the Gazette] came forth fresh, full of vigor, and was accepted by the people as an harbinger of good—a companion of knowledge, the medium for the transmission of useful information.

It crept in its infancy; it walked in its youth; in its manhood it has always acted the manly part; and now, that its mission is through; its days are numbered, can we consign it to rest, without regrets? Full of hope that the good it has done in the past, will compensate and atone for the sacrifice we have made, we place it gently upon the shelf to gather the rust of coming years, and may its memory be ever revered by our entire community.

J. Rhutsen Schenk.

And in a separate item, Schenk wrote:

TO OUR SUBSCRIBERS.─ We have disposed of this paper, and the material upon which it is printed, to Chas. Tomlinson. It is the purpose of Mr. Tomlinson to establish at once a first class Democratic sheet, from the office, to be called THE DEMOCRAT. We shall remain in charge, and will be at all times happy to meet our old friends, and do their work for them, well, promptly, and at reasonable rates. It is our intention to have the office stocked with material for the execution of all kinds of printing, and we have the ability to do it; so bring along your work. All communications intended for this establishment will be directed to THE DEMOCRAT. We hope there will be no falling back in this new enterprise; but that all will step up, and dress up in front, and show that their hearts are with us, and a little of their money too.

With the Gazette in such good shape it is a wonder that Schenk decided to give it up, and even more so, to turn it over to a Democrat. Hubert Schmidt conjectured that his war experience had taken the fight out of him. On July 11, 1866, Schenk wrote this editorial:

Valedictory. With this issue of the Gazette, its publication will cease. It is with many regrets that we make the announcement, but circumstances have occurred compelling suspension. We have disposed of the material of the office, and the present owner [Charles Tomlinson] intends to found a new paper, Democratic in politics, and in view of the fact desires a new title.

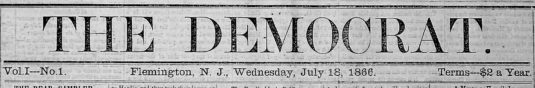

The next issue of the paper, published on July 18, 1866, had a completely different masthead (above) with a completely different name. But despite his own politics, Schenk had decided to stay on as editor. He wrote:

The next issue of the paper, published on July 18, 1866, had a completely different masthead (above) with a completely different name. But despite his own politics, Schenk had decided to stay on as editor. He wrote:

IN A NEW POSITION.─ The readers of the Gazette, will as usual find in the columns of The Democrat, a full report of all matters worthy of publication, pertaining to the interests of our town, township or county. As will be noticed at the head of this column, we retain a position on this journal, and in order that we may the more fully carry out the work before us, we desire communications, from all sections, on any subject, of benefit to the public. We desire to have a large amount of local reading matter; it is one of the main columns in the support of a county journal. We desire the people to know that we intend to have a live time in the make-up of the locals. We will devote the attention to it that the times demand. We know that the Gazette was always sought after for its home news, and if you want to continue to receive a full share subscribe at once for The Democrat.

As a result of this purchase, there was a transition period in which “The Democrat” and “The Hunterdon County Democrat” were both being published at the same time. In June 1867, Bellis finally gave up the paper, selling it to Dr. H. B. Nightingale, who proved to be an able editor, with Lewis Runkle as his local editor. The first edition under Nightingale’s direction was published on June 19, 1867.

As a result of this purchase, there was a transition period in which “The Democrat” and “The Hunterdon County Democrat” were both being published at the same time. In June 1867, Bellis finally gave up the paper, selling it to Dr. H. B. Nightingale, who proved to be an able editor, with Lewis Runkle as his local editor. The first edition under Nightingale’s direction was published on June 19, 1867.

Although the Democratic party was dominant in Hunterdon County, having two Democratic newspapers in a place like Flemington did not make much sense. It was inevitable that one would drop out or that the two papers would merge, which is what happened on July 3, 1867, when the two became one, with Charles Tomlinson as owner, Dr. Nightingale as chief editor and J. Rhutsen Schenk as local news editor. Lewis Runkle was apparently demoted to reporter. Hubert Schmidt wrote:

The amalgamation was so smooth that one cannot help wondering whether it had not been agreed upon from the time of Nightingale’s purchase of the Hunterdon Democrat.”

The Hunterdon County Democrat came to be the primary newspaper for supporters of the Democratic party, not just for the Flemington area, but the whole of Hunterdon County, just as the Hunterdon Republican had been for the Republicans since its inception. However, the Republican was somewhat handicapped by the fact that in the 19th century, the county was strongly Democratic. As Schmidt observed, it was as strongly dominant in the county as the Republicans had become when he was writing in the 1960s. But the Hunterdon Republican carried on as the principal opposition newspaper to the Democrat, and did not succumb until 1953. The Hunterdon County Democrat thrived during the years when all newspapers thrived, but as history continually demonstrates, times change. It has been a sad experience witnessing the demise of newspapers in general, and the decline of the Democrat in particular. As far as coverage of local and county politics is concerned, it is nothing close to the newspaper it once was. And not all that long ago, the Lambertville Beacon, the most reliable and beloved of local papers in the southern part of the county, was terminated by its parent company.

We cannot blame the newspaper owners. They do not act out of malice, but by necessity. Readers have changed their habits and advertisers have followed them to the internet. Until some new business model emerges that can support good local reporters, our ability to understand the important issues facing our communities will continue to suffer.

Footnotes:

- As in the previous articles on this subject, I have depended heavily on the pamphlet written by Hubert G. Schmidt titled “The Press in Hunterdon County, 1825-1925” as well as abstracts of the Hunterdon Gazette compiled by William Hartman. ↩

- According to Wikipedia, quoting the Oxford English Dictionary, the name shinplaster comes from the quality of the paper, which was so cheap that with a bit of starch it could be used to make paper maché-like plasters to go under socks and warm shins. ↩

- Hunterdon Gazette, Jan. 18, 1838. ↩

- I have written about this major event for Hunterdon County in a previous post, “The 175th Anniversary of Delaware Township”. ↩

- Hubert Schmidt mistakenly thought that the office George was running for was “village council,” one of Schmidt’s few errors. ↩

- Trenton State Gazette, v. VI, issue 1589, p. 2, Friday April 9, 1852, as shown on Genealogy Bank. ↩

- A search of the Philadelphia papers on Genealogy Bank for George’s obituary was unsuccessful. ↩

- Hunterdon Gazette, Dec. 24, 1856. Beers Atlas of 1873 shows the lot owned by Robert Ramsey, who was married to the daughter of John Volk in 1864. ↩

- Hunterdon Co. Democrat, April 30, 1878, vol. 40, no. 36. Note—I have not checked on issues of the National Baptist to see if they published an obituary for Charles George. Most likely it did. ↩

- A copy can be found at the Hunterdon County Historical Society. ↩

- Herbert Schmidt mistakenly wrote “Adam” rather than Alexander, and I followed course until I realized my mistake in 2020. ↩

- The name Rhutsen had various spellings, but this seems to be the preferred one; also Schmidt consistently uses the spelling Schenck, but in the Gazette the spelling was always Schenk. ↩