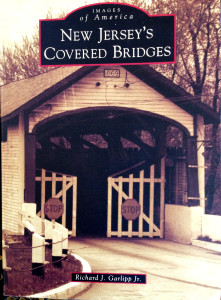

Richard J. Garlipp, Jr. New Jersey’s Covered Bridges, Images of America, Arcadia Publishing, 2014.

If you’ve ever had first hand knowledge of a story in the newspaper, chances are you’ve said to yourself, “the reporter got it wrong.” This also happens with books, including this one. Mr. Garlipp has long been a student of the history of covered bridges, and has undertaken a large and under-reported subject. But Arcadia books are not held to a very high standard and do not engage in fact-checking, so the results are sometimes a disappointing mixture of fact and fantasy. History is challenging, and mistakes are all too easy to make, as I have often learned to my dismay. I just wish this book had been better.

Don’t get me wrong—there is a lot to like about this book. The pictures are wonderful, a considerable collection of long-gone covered bridges, far more than most people realize once existed in New Jersey. Some of those bridge pictures are surprising. I am particularly fond of the Greek Revival facades that were built for the Crosswicks Bridge on the Burlington-Mercer border (p. 16-17) and the bridge over Fenwick Creek in Salem (pp. 20-21), with its warning: “Keep to the Right as the Law Directs” underneath the spreading wings of a patriotic eagle.

When it comes to patriotic, you can’t beat the depiction of Washington’s reception in 1789 by the Citizens (or ‘Ladies,’ depending on which version) of Trenton, made by N. Currier in 1845. (The picture was not included in this book, but can be found on Google images.) The Currier painting seems to show that there was a covered bridge over the Delaware at Trenton. In fact, Washington had to cross the Delaware River by ferry. What Currier saw was the Trenton Lower Bridge (pictured on p. 33 of the Garlipp book). This stunning bridge, the first one to span the river, was not built until 1806. Its façade, which looks faintly Dutch, had four arched entrances for two traffic lanes and two walk ways. Its five-span Burr truss construction had five long timber arches supporting each span. The photograph is impressive. I imagine that travelers in 1806 must have been amazed.

And speaking of entrances, the one to the Lambertville-New Hope bridge was also outstanding (p. 61). How different Lambertville would be if that lovely gateway were still there. The rather heart-breaking photograph on p. 62 shows what happened to it in the flood of 1903.

A bridge that was new to me was the covered bridge built in 1851 spanning the Alexauken Creek near Lambertville. There is a beautiful photograph of that bridge on page 24. (See also page 102.) It was built using a design invented by Ithiel Town, known as a Town lattice-truss bridge. If only that bridge were still standing. But it caught fire in 1913 and was completely destroyed. Judging by the Beers Atlas of 1873, the bridge would have been somewhat upstream from the creek’s outlet at the Delaware River, probably on the old River Road.1

In the introduction to “The Gateway Region,” being the eastern counties of Essex, Passaic, Hudson, Union and Middlesex, the author states that evidence of covered bridges in this area is quite scant. This is surprising, given the early urbanization in this area, where good transportation must have been taken very seriously. Mr. Garlipp writes that the first covered bridge in the state was built in 1772 on the Raritan River, a mile upstream from New Brunswick. There must have been other bridges across the Raritan, as well as the Millstone, Hackensack and Passaic Rivers. The only other early bridge shown in this area was the one at Little Falls in Passaic County (p.57; a lovely photo of that bridge was mistakenly included in a different chapter, on page 24). What a shame that records of the early east Jersey bridges have been lost.

I was eager to see what was written about the Green Sergeant Covered Bridge, as it is one I know something about. Very nice pictures, but alas, several errors. On page 7 the author wrote that Charles Sergeant was the builder, and the bridge was named for his son. True, the bridge took on the name of Richard Green Sergeant, but his father Charles Sergeant was not the builder. He settled there in 1805, but there was a bridge there long before 1787 when the freeholders met to decide on repairs.

The author states that Sergeantsville was established in 1700, which is completely wrong, and that a “tribe of Delaware Indians” camped near the bridge “after the Iroquois had conquered them.” (p. 104) Yes, there is evidence that Indians were present in the area; arrowheads and spear points were once abundant there. But why bring in the Iroquois, who never “defeated” the Indians of New Jersey? And, since I’ve lived in the neighborhood of Sergeantsville for 37 years, I was surprised to read this: “Also on her visit to Sergeantsville . . .”2

One other note on the covered bridge. On page 103, the author has chosen to show a photograph of a covered bridge that probably is not the Green Sergeant bridge. As he points out, the “curved portal framing,” is not seen on any other picture of the bridge, and I see no reason to assume it is the same. This being an Arcadia book, there is no way to know where the picture came from.

Mr. Garlipp made a misleading statement when he wrote that John Reading purchased his land from “local Native Americans” in 1703, suggesting this was a private land purchase, when in fact, Reading and two others bought a tract of 150,000 acres on behalf of the West Jersey Proprietors. Then Reading had to apply for a survey based on the number of shares he owned to acquire his own plantation north of Stockton.

I have listed these problems partly to set the record straight, and also to observe that if the author was wrong about things I know about, it leaves me uncertain about all the information he has provided about the other bridges, and that is unfortunate given how much work must have gone into this book.

The catalog of New Jersey covered bridges is a surprisingly long one. How nice it would have been to see a map showing their locations. This may have been a constraint imposed by Arcadia. It would also have been nice to have a list of bridges by date, or a list of all the bridges destroyed by the flood of 1903. But that may be asking too much of an Arcadia book.

The best documented covered bridges in New Jersey spanned the Delaware River, and they were all damaged by floods. It appears that the major floods took place in 1841, 1862, 1903, 1933 and finally 1955, by which time the last of the covered bridges over the Delaware were gone. Here is a list of the 16 New Jersey bridges, based on information in the book, plus a little help from Wikipedia.

1806, Lower Trenton Bridge; replaced in 1876

1806, The Easton-Phillipsburg Bridge; survived the floods, but weakened by trolley traffic; replaced in 1895

1814, Lambertville-New Hope Bridge, destroyed in 1903, replaced in 1904

1814, Centre Bridge (Stockton, NJ to Centre Bridge, PA), destroyed by flood in 1841 and by fire in 1923; replaced by 1927

1834, Washington’s Crossing Bridge (M’Conkey’s Ferry), destroyed in 1903; replaced in 1904

1835, Yardley-Wilburtha Bridge, destroyed in 1903, replaced in 1922

1836, The Belvidere Bridge; damaged soon afterwards, but repaired, destroyed in 1903.

1836, Dingman’s Ferry Covered Bridge, destroyed, rebuilt, destroyed in 1865. replaced in 1889.

1837, The Riegelsville Bridge, destroyed in 1903; replaced 1904

1842, The Milford-Upper Black Eddy Bridge; damaged in 1903; replaced in the 1930s.

1844, The Frenchtown-Uhlerstown Bridge, damaged in 1903; replaced in 1931

1855, Point Pleasant-Byram Bridge, destroyed by fire 1892, then by flood 1955

1855, Delaware Station, Warren Co., built for train traffic; replaced 1871

1856, Lumberville-Raven Rock Bridge, approved in 1835, but delayed until 1853 when construction began; damaged in 1903; condemned in 1944; replaced with a footbridge in 1947

1861, Calhoun St. Bridge, replaced in 1884

And the last covered bridge built to span the Delaware River:

1869, The Columbia, NJ-Portland, PA Bridge; survived the flood of 1903 and a tornado in 1929, converted to a foot bridge in 1953, destroyed in the flood of 1955.

The bridges speak of another time, when everyone traveled far more slowly and yet seemed to have more time in their days. As the author noted, Pennsylvania, New York and New England have kept many of their covered bridges. But New Jersey did away with them all, except for the one that local residents fought for.

As depicted in this book, the damage done to the old bridges by periodic floods and occasional fires was disastrous. If nature had not done away with these bridges, the automobile and the truck surely would have. Admittedly, preserving the covered bridges that once crossed the Delaware River would be too impractical. But the covered bridges that crossed New Jersey creeks deserved a better chance than they got.

There Are Still Bridges To Save

Even without the covered bridges, Hunterdon County has two other types of bridges that must not be ignored—the stone arch bridges and the metal truss bridges. I got a crash course on metal truss bridges back in 1998 when a one-lane bridge over Plum Brook was scheduled to be replaced with a modern two-lane bridge. My neighbors and I were so dismayed, we scrambled to get this modest little bridge listed on the National Register of Historic Places, hoping that would save it from destruction. Much to our surprise, the State Historic Preservation Office approved the application, and our little bridge became the first metal truss bridge in New Jersey to be so recognized. As a result, the county was obliged to save the metal trusses and to widen the bridge far less than had been planned. It’s not the bridge it used to be, but we can consider it saved, as long as the county continues to maintain it. I am very proud to have written the application, the only application to the National Register that I have ever done. What did not get included was a biography of the bridge engineer who constructed the Plum Brook bridge and several others in the county—John Scott of Quakertown and Flemington. I hope someday to give him his due.

Since 2000, the county has had several other metal truss bridges to deal with, and generally the bridges have gotten more attention than they used to. Today another bridge is being ‘updated’—this one far more significant than the one over Plum Brook. It is the Raven Rock bridge over the Lockatong Creek. Delaware Township residents worked hard to see that the county came up with a plan that respected the architecture of the bridge, but the one non-negotiable item—a guide rail inside the metal trusses—will change the look of the bridge, and not for the better. The bridge was scheduled to reopen this month, but this past winter’s abominable weather has delayed the event.

Update: On August 23, 2014, I published an article on the Raven Rock Road Bridge over the Lockatong here.

Footnotes:

- Much to my delight, the bridge can be seen on the 1883 Aerial View of Lambertville, on the very far right of the picture. ↩

- I appreciate the author giving me credit for some ephemeral stories about the bridge, but as my readers know, I had a lot more to say on the subject. Here are some links: Green Sergeant’s Covered Bridge; Covered Bridge Tales; Sparky’s Roadhouse Continued; The Covered Bridge in the Automobile Age; and Citizens to the Rescue. Also see Egbert T. Bush’s article Story of Green Sergeant’s Bridge and Its Builders. ↩

Ron

April 12, 2014 @ 8:19 am

I have to wonder how many tourism dollars Hunterdon loses every year to Bucks County, which has kept a strong association with the covered bridge. I wonder if it was short-sightedness on the part of New Jerseyans, or a fortuitous backwardness on the part of Pennsylvania that led to this situation.

Neil Cubberley

April 14, 2014 @ 1:17 pm

Some of my favorite memories of the Green Sergeants Covered Bridge were in the early 1950s. When Ruth Phillips was the principal at Delaware Township School, we had a spring picnics on the creek beside the bridge. One time (maybe 1954 or ’55) instead of having my mother drive me, I decided to ride my horse from our farm on Grafton Road to the bridge. When I got there, everyone wanted to ride my horse.

Walter Colombo

April 3, 2016 @ 10:53 am

I know what you mean when you say history can be tricky. I once lived down river from the Dingman’s ferry bridge and on a summer’s night we could hear the clap of the loose deck boards as cars went over them, a pleasing sound actually. And knowing the family I’m told it was erected in 1900 from the three best sections salvaged from a bridge that once spanned the Susquehanna. So if you take a weekend trip, leave your easypass at home, it isn’t accepted there and expirence the thrill of driving over the loose deck boards of a narrow 115+ year old used bridge the has survived many floods who have blown away many other bridges!

p.s. I also get disappointed when I read history books with errors, which is why when I volunteer for the park system to be the leader on history tours I have my research backed up by original sources. Another book which I do like yet is riddled with errors is “Place names of Hunterdon County”