Hunterdon County Politics in the 1850s

I am going to step away briefly from the life of John C. Hopewell to shed some light on a political movement that Hopewell and many other Flemington notables got caught up in.

As shown in the previous post, “One Man Makes a Difference,” John C. Hopewell was involved in practically every municipal improvement in Flemington that took place during the years of 1854-1880s. But for some reason, this man who took leadership positions in everything he tried, chose to stay more or less out of politics, during a time when politics was on everyone’s mind (not unlike these times). It was not until 1856, two years after moving back to Flemington, that Hopewell got involved, and then only in a minimal way.

One would expect a successful farmer and businessman like Hopewell to join the Whig party, which had replaced the old Federal Party and was led for many years by Henry Clay. But he did not.

(Note: I had intended to make this a one-article sidetrack to discuss Hopewell’s political involvement and the nature of Hunterdon politics during his life before going on to write about the bank building that he built on Flemington’s Main Street. What made me think that a subject as important as politics during the years leading up to the Civil War could be covered in one article? I debated about postponing this discussion until after describing the bank building, but the building was erected during the last years of the war, and some historical context was needed. Also, because of the divisions we suffer from today, I felt compelled to learn more about the divisions of our past.)

Hunterdon County’s Whigs

The Whig party had been around ever since Andrew Jackson was president. In fact, he was the reason the party got organized. Jackson was a Democrat, and Hunterdon County was Jackson territory, except in the towns where merchants were concentrated. Merchants wanted a strong banking system and were not happy when Jackson withdrew deposits from the national bank. I thought it would be interesting to know who in Hunterdon County belonged to the Whig party and found a list of names in a story about a Hunterdon Whig convention that took place in 1848. No doubt the list is not exhaustive, but it is interesting.

As you will see, it was not uncommon for several members of the same family to join the party. This was also the case with the Democratic party. (For those of you not interested in the following list of names, feel free to scroll past it.)

The Whigs of Hunterdon in 1848 were:

Nelson Abbot, Daniel Allen, Conrad P. Apgar, Peter C. Apgar,

Abraham Banghart, Thomas Banghart, Jr., John Barber,

Johnson Barber, Adam M. Bellis,1 William Biggs, William W. Bird,

James H. Blackwell, Lambert N. Boeman, Amos Bonham,

William Bonham, Henry Boss, Sylvester Bowlby, Henry C. Buffington,

E. R. Bullock,

John L. Case, John Chapman, Thomas H. Chapman,

Peter I. Clark, Samuel Clark, W. F. Combs, John Conover,

Elisha Cooley, James Cooley, Samuel Cooley, Wm. V. Cooley,

Dickenson M. Cox, David Craig, Abraham. V. Cregar,

Wm. Creveling,

Hiram Dilts, Samuel W. Dilts, John Duckworth,

Azariah W. Dunham, Nehemiah Dunham,

Wm P. Emery, George A. Evans, Peter Eveland,

Caleb F. Fisher, Jacob F. Fisher, James J. Fisher,

John E. Forman, Robert Foster, Samuel Fritts, Abraham Fulper,

George W. Gaddis, James P. Gary, Charles T. Green,

Conrad Gulick,

William W. Hall, Peter V. Hartpence, Jonathan Higgins,

Samuel M. Higgins, Alexander Hill, Samuel Hill, William Hill,

John H. Hoffman, Paul K. Hoffman, Charles W. Holcomb,

Elisha E. Holcomb, Ferdinand S. Holcomb, John R. Holcomb,

Richard Holcombe, William F. Holcombe, Dr. John Honeyman,

John Hoppock, Ludwig Horton, D. B. Huffman,

James P. Huffman, John H. Huffman, Joseph Huffman,

Ralph Huffman, Augustus Hunt, Edward Hunt,

Henry W. Johnson, Thomas P. Johnson, Ross Jones,

Robert Kilgore, John R. Kline, Leonard P. Kuhl,

Matthew P. Lane, Isaiah P. Large, John K. Large, William Large,

Dr. Justis Lessey, W. J. Lindaberry, John N. Lowe,

Jacob S. Manners, Robert M. McLenahan, Asa McPherson,

James Melick, John W. Melick, Nicholas E. Melick, Peter Melick,

Levi M. Mettler, Hiram Moore, George Muirhead,

Willard Nichols (ed. of the Gazette), Peter F. Opdycke, Lewis S. Paxson,

Theodore Polhemus, Jacob S. Prall, John S. Prall, William R. Prall,

Lewis M. Prevost, John W. Priestly,

John P. Quick, Peter P. Quick,

Alexander Rea, George Rea, Runkle Rea, John G. Reading,

Jacob Reed, John C. Reed, George P. Rex, George W. Risler,

Theo. H. Risler, William R. Risler, A. B. Rittenhouse,

Ogden Roberson, Wm Robinson, Wm Ross,

Andrew B. Rounsavel, Ralph W. Rudebock, John Runk,

John V. Schamp, Edward Schenck, Jacob Schenck,

Mahlon Schenck, Joseph Servis, William Servis, Peter Sigler,

Jacob Skinner, Wm. H. Slater, Mahlon Smith, Martin Smith,

James Snyder, James Stevenson, Morris Stiger, Nathan Stout,

James D. Stryker, Derrick A. Sutphin, Henry Suydam,

Charles R. Swallow,

Peter Q. Tenbrook, John V. Thatcher, Nelson Thatcher,

Mordecai Thomas, Aaron Thompson, Joseph Thompson,

Chas. Tomlinson, Francis Tomlinson, Aaron Trimmer,

John B. Vanderbeek, Richard Van Liew, Peter Van Pelt,

George Vansyckle,

John H. Wakefield, Elijah Warford, Jonathan M. Welsted,

Wm. Wetherill, Robert L. Williams, David Williamson,

Jacob S. Williamson, John H. Williamson, John S. Williamson,

Charles Wilson, Israel Wilson, Elias Wyckoff,

Jacob S. Young, John A. Young, Nelson V. Young,

Peter R. Young, Wm R. Young, and William W. Young.

At the national Whig Convention of 1852, a hero of the Mexican War, Gen. Winfield Scott, was nominated for President. This was the third time the Whigs had chosen a former general rather than a seasoned politician. It had worked with Wm Henry Harrison in 1840 and with Zachary Taylor in 1848. Unfortunately, both men died shortly after taking office. Taylor was replaced by his vice president Millard Fillmore.

At their 1852 convention, the Democrats nominated Franklin Pierce of New Hampshire who had also served in the Mexican War, and who, even though from a northern state, was not hostile to the interests of the South. The race was complicated somewhat by the presence of a third party, the Free Soilers, who were opposed to the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Even so, Pierce won easily.

Scott’s loss was a demoralizing defeat for the Whig party—so much so that when Raritan Township met in April 1853 to elect local officers for the year, only one Whig candidate won, George W. Risler, who beat Democrat Robert Thatcher by only six votes.

The only other offices won by Whigs that year were for Overseer of the Poor (Mahlon Smith, 181 votes, v. Wm C. Bellis with 171); Surveyor of Highways (Adam M. Bellis, 170, v. Abraham Gulick, 154); and Judge of Election (Samuel M. Higgins, 182, v. Robert K. Reading, 175). Two Justices of the Peace were elected, a Democrat named Pittenger with 163 votes, and a Whig, Edward R. Bullock, with 180 votes. Three men won the position of Commissioner of Appeals: two Whigs (William Hill with 184 votes & James H. Blackwell with 166) and one Democrat (Alexander V. Bonnell with 185).2

In 1854 the Whigs made no regular nominations to the Town Committee at all. According to the Gazette: “The election resulted in the entire success of the Democratic Ticket, with the exception of Mr. George W. Risler (Whig,) who ran on the ‘Independent Ticket,’ and was elected Town Committeeman by nine majority, over his opponent, Henry Anderson.”

Birth of the Republican Party

In my article “A Store, A Bank, A Mansion,” I discussed the big events of 1854, including the creation of the Republican party, which was triggered by passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act that year. For those committed to stopping the spread of slavery to new states and territories, this legislation was a betrayal; it cancelled the hard-won provisions of the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which was Henry Clay’s greatest legislative achievement. The Compromise had prohibited slavery north of the 36th parallel, which included what became the states of Kansas and Nebraska. The Kansas-Nebraska Act, drafted and promoted by Stephen A. Douglas, allowed new states to decide for themselves whether or not to permit slavery within their boundaries. The problem with that was the plantation aristocracy of the South. The big planters with their hundreds of slaves would now be free to move west and thereby establish slavery throughout the country. Douglas thought the Act simply allowed territories and states to outlaw slavery within their borders. The South thought the Act meant that they could not,3 which explains why a piece of legislation which was intended to solve a problem created a bigger one.

The new political party adopted the name ‘Republican’ at a meeting in Ripon, Wisconsin on March 20, 1854, and it organized on the state level near Jackson, Michigan in July 1854. Soon there were Republican party tickets throughout the Midwest. One of the party’s members and strongest supporters was Abraham Lincoln, but he did not commit himself until 1856, the next presidential year.

This was also the case in Hunterdon County. The Republican party did not really get organized in the County until 1856. (I will deal with the campaign of 1856 in the next post.)

Politics & Newspapers

The best way to find evidence of political activity in Hunterdon in the 1850s is to look to the newspapers. In the mid-19th century, local papers were unabashedly political.

Henry C. Buffington was the publisher & editor of the Hunterdon Gazette from 1843 to 1854. The original editor of the Gazette, founded in 1825, was Charles George, who tried very hard to avoid politics, but by the time Buffington took over, the Gazette had become the Whig alternative to the Hunterdon County Democrat. (See “Charles George & The Hunterdon Gazette” and “Chas. George & The Gazette, part two.” George’s successor in 1838, John S. Brown, turned the paper into a Whig organ, prompting the creation of a Democratic paper to counteract it.)

The poor showing by Whigs in the 1852 and 1853 elections was probably enough to convince Buffington it was time to move on. By March 22, 1854 he had handed the paper over to Willard Nichols, the same month that the Kansas-Nebraska Act was passed.4

Willard Nichols was born in New York on November 26, 1814, making him about the same age as John C. Hopewell. It isn’t clear how he came to be interested in running a newspaper in a little town like Flemington. He seems to appear out of nowhere. (I could not find him in the 1850 census.) Buffington probably agreed to sell the paper to him because at the time Nichols was a supporter of the Whig party.

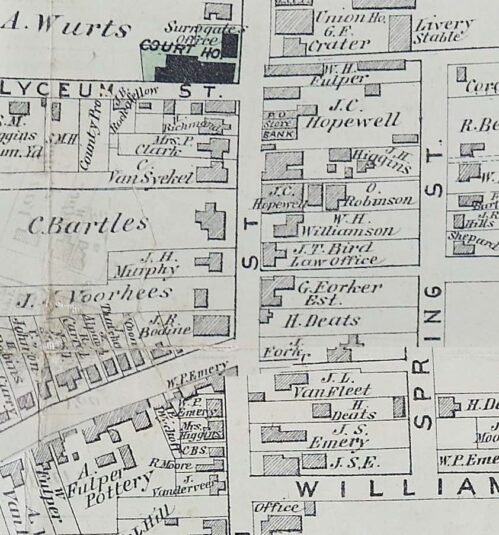

The Home of the Gazette

When Nichols took over editorship of the Gazette, Henry C. Buffington was still living on the property sold to him by John & Joseph Reading and John C. Hopewell. So, Nichols set up shop in the other property owned by John G. Reading, the Fisher-Reading Mansion, across the street from the Buffington place. On November 28, 1855, John G. Reading advertised his mansion for sale in the Gazette:

RARE CHANCE! DESIRABLE PROPERTY IN FLEMINGTON FOR SALE! The subscriber will sell at Public Sale, on Saturday, December 22, on the premises, at 1 o’clock P. M., the HOUSE and LOT now in the tenure of Willard Nichols, situate on Main street, in Flemington, a few rods south of the Court House. [emphasis added] . . . The improvements upon it are a commodious two-and-a-half story Dwelling House, with 3 rooms on the first, and five rooms on the second floor, with an excellent cellar underneath the whole. There is also attached a building seventeen by twenty, suitable for any kind of an office, bookstore or millinery establishment. . . . In short, it is one of the most desirable properties in Flemington. . . . For further particulars, or a view of the premises, call on the undersigned. JOHN G. READING.

By 1856, Buffington had moved to Illinois, probably in the company of James N. Reading. It was from the town of Morris in Grundy County that Buffington and wife Elizabeth sold their Flemington lot to the same partnership that had sold it to Buffington, the Reading brothers and John C. Hopewell.5

Once Buffington left for the west, Willard Nichols moved out of the mansion and into the lot Buffington had occupied. It was located where the Methodist Church is now, at the corner of Main Street and Maple Avenue. When the Beers Atlas was published in 1873, the lot was owned by Hon. John T. Bird, Counsellor at Law and Democratic Congressman. Maple Avenue did not yet exist in 1873 and appears simply as an alley between the Bird lot and property of George Forker.6

Once Buffington left for the west, Willard Nichols moved out of the mansion and into the lot Buffington had occupied. It was located where the Methodist Church is now, at the corner of Main Street and Maple Avenue. When the Beers Atlas was published in 1873, the lot was owned by Hon. John T. Bird, Counsellor at Law and Democratic Congressman. Maple Avenue did not yet exist in 1873 and appears simply as an alley between the Bird lot and property of George Forker.6

On Nov. 18, 1857, this advertisement appeared in the Gazette:

VALUABLE HOUSE AND LOT FOR SALE. THE Subscribers will offer at Public Vendue, at the house of Geo. F. Crater [the Union Hotel], at 2 o’clock, P. M., on Saturday the 19th day of December next, all that valuable House and Lot of Land centrally located in the village of Flemington, recently occupied by Willard Nichols, a part of which is now used as an office for the issuing of the Hunterdon Gazette [emphasis added]. This property is in good repair, having very recently been newly roofed and painted both inside and out, and also newly papered. It is well adapted to the convenience of persons desiring a small Storeroom connected with their dwelling. The location for a Store is very central, convenient and desirable. Attendance will be given and conditions made known on the day of sale by JOHN C. HOPEWELL, JOHN G. READING.

Since Hopewell was one of the executors of the estate of John G. Reading’s brother Joseph, who had died on Oct. 21, 1857, he was acting in both capacities, partly as owner and partly as executor. But why had Nichols left the property? The reason was reported in the October 14th issue of the Gazette, explaining that Nichols had discontinued his connection with the paper and left town. But while Nichols was in charge of the paper, he made use of it to promote his new political allegiance.

The Campaign of 1854

The Whig Convention

Even though nationally the Whig party was on its last legs, the Whigs of New Jersey still held conventions in the fall of 1854 to name Congressional candidates. The Hunterdon County Convention took place on September 23, 1854 at Crater’s Hotel to select delegates to the district-wide convention to be held in October. As the Gazette reported, “Col. Peter I. Clark was called to the Chair,” and Willard Nichols was named secretary of the convention. Here is a list of delegates as reported in the Gazette:

From Raritan Township: George A. Evans, Runkle Rea, John G. Reading, William R. Risler and Ralph W. Rudebock; Geo. W. Risler named as an alternate for Rudebock.

From Readington Township: William Biggs, Thomas P. Johnson, John K. Large, Levi M. Mettler, Theodore Polhemus, and Joseph Thompson.

From East Amwell: William W. Hall, Jacob S. Manner, John W. Priestly, William Servis and Nathan Stout.

From West Amwell: Nelson Abbott, Jacob F. Fisher, William F. Holcombe, Charles Wilson and Nelson V. Young.

From Delaware Township: John Barber, George W. Gaddis, Ferdinand S. Holcombe, Justus Lessey, and Hiram Moore.

The Anti-Nebraska Convention

On September 27, 1854, a week after the Whig convention was held in Flemington, a notice was published in the Gazette for an “Anti-Nebraska Convention” to be held October 11th for voters of the Third Congressional District. Hunterdon delegates were to be Hiram Bennet, Conrad P. C. Apgar, Edward R. Bullock, Elijah W. Iliff, William Emery, Leonard P. Kuhl, William B. Srope, Peter W. Burk, Abraham V. Vanfleet, and George F. Wilson. These men had been Whigs back in 1848. They were strongly opposed to passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act and had become members of a very loosely organized party, much like the Republicans who had organized just a few months earlier. Some disaffected Democrats also joined them.

During the campaign, Nichols was still a supporter of the Whig party, and opposed to the Hunterdon Democrat which strongly supported Stephen A. Douglas and the Kansas-Nebraska Act. As Hubert Schmidt wrote, “Nichols followed his predecessor’s lead at first, and waged bitter war on Douglas, the Kansas-Nebraska Act, and the spread of “that detestable institution, ‘slavery.’”7

In fact, the political scene in 1854 was incredibly fluid. For decades, the two old parties, the Whigs and the Democrats, had each managed to maintain a national appeal by ignoring the issue of slavery. But both Whigs and Democrats had northern and southern factions, i.e., groups opposed to slavery and groups supporting it. Once the Kansas-Nebraska Act was passed, it was no longer possible to ignore the issue and the two parties started to split apart. Sectionalism was the word used to describe the growing opposition between the North and the South.8

Nationally, some of the parties contending for office in 1854 beside Whigs and Democrats were the Republican Party, the People’s Party, the Fusion Party, the Anti-Nebraska Party, and Free-Soilers. There was some kind of anti-slavery party in every northern state. In addition, the Temperance Party was growing stronger.9 As David Potter wrote in Impending Crisis, a reporter observing the Congressional session of 1855 was unable to put a party label on the Congressman on the floor of the House, often because many of them had allied with both the Anti-Nebraska groups and what Potter called the nativist parties.

On October 11, 1854, the Whig convention that had been advertised in the Gazette took place in Somerville to name congressional candidates for the third Congressional district which included Hunterdon, Middlesex, Somerset and Warren. According to William Gillette, the third district “witnessed the most momentous development” in party alignment of all the NJ districts.

The Whig convention and the newly formed anti-Nebraska convention met separately but simultaneously in the same courthouse; then they combined and nominated a coalition candidate, nativist James Bishop, who firmly opposed the Nebraska policy as did the platform of the convention.10

James Bishop of Morristown won the nomination and ran as the Opposition Party candidate against the incumbent Democratic Congressman, Dr. Samuel Lilly of Lambertville. Lilly had followed the party line and in May 1854, voted to approve the Kansas-Nebraska Act. This sparked quite a lot of outrage back home. Willard Nichols wrote an editorial in September commending the delegates chosen at the Hunterdon Whig convention, in which he noted

We rejoice in the fact, that they [the delegates] are men not at all likely to be swerved from the true course by any ism, or newfangled issue that may be presented [like slavery]. If the rest of the delegation are men of like mark, we have nothing to fear. They will select a man for whom every good Whig can labor with a zeal worthy the great cause, and for whom every good Democrat, who feels himself mis-represented by our late dough-faced Congressman (and the name of such Democrats is legion), can cheerfully vote.

The term ‘dough-faced’ was used to describe northerners who supported the expansion of slavery in the west. The combination of Whigs, members of the Anti-Nebraska party, as well as disenchanted Democrats was enough to remove Lilly from office and replace him with James Bishop.

Despite this success, the fluid nature of politics in 1854 did not result in a stronger Whig party—quite the opposite. By 1855, the county party followed the national party and no longer put forward candidates for office. Former Whig party members were looking for a new home.

One would expect the new editor of the Gazette, Willard Nichols, to move toward the Republicans, since the Democrats were properly cared for by the Hunterdon County Democrat, founded in 1838, and edited, starting in 1853 (and for many years thereafter), by Adam Bellis. (Bellis was “as intensely a Democrat” as the previous editor, George C. Seymour was, but “not as intelligent.”)11 One would also expect the many Hunterdon members of the Whig party to migrate to the Republicans. But that is not what happened.

The American Party

Although Willard Nichols started out in 1854 as a strong supporter of the Whig party, by October 1855, he was committed to “Americans Ruling America.” This was the slogan for a new party, called the American Party.

As Egbert T. Bush wrote in “Hunterdon Businesses in 1850,” the party began as a secret society in Louisiana that called itself the ‘Native American Party.’ He described an advertisement in the Directory which was

a “Prospectus of the American Banner,” a weekly newspaper published simultaneously in Philadelphia and Camden, Intended to be the Advocate and Expositor of the Native American Principles, as laid down by the National Convention of July, 1845.

Despite being strong enough in 1845 to hold a national convention, this version of the party did not get very far. Then in 1849, another secret society formed in New York City called the ‘Order of the Star-Spangled Banner.’ Being a secret society, it had secret rituals, rules and codes, and when asked about them, the members were told to answer “I know nothing.”12 It did not take long for them to acquire the name “Know Nothings,” even though they called themselves the American Party.13 Willard Nichols never used the name in the Gazette.

Among the many things that members were sworn to was never to vote for any candidate for public office who was foreign-born or a Catholic. At the time, a great number of immigrants from European countries, especially Ireland and Germany, were coming to America to escape the suffering they experienced in their homelands. These people were generally Catholics and generally poor, taking jobs in areas requiring hard physical work, like mining and railroad construction. They were mostly Catholic Irish, as opposed to the Protestant Irish from Ulster and the Scotch and English who had emigrated to American so many years before, and were mostly Presbyterian, with Baptists coming in a strong second in Hunterdon County.

The descendants of Protestant European immigrants of the 18th and early 19th century were not comfortable with this new wave of residents with different habits and lifestyles. (Their hard-drinking ways helped inspire the Temperance movement which grew strong around this time).

The people who were hostile to these immigrants are called nativists by today’s historians, which I find very ironic, since those same people also had no sympathy for the original natives. They did their best to make the new immigrants feel unwelcome. And because so many belonged to the Catholic Church, which had long been associated with monarchical governments, the Church also came in for abuse.

Party Members

Egbert T. Bush wrote that

The “Know-Nothings” were much in evidence and apparently much feared in the early 1850’s. I remember well how sneeringly the few in our neighborhood were pointed out, and how solemnly their organization—at first a secret one—was denounced as a menace to the country.14

I am certain that those people who sneered at the Know-Nothings were Democrats. Adam Bellis in the Hunterdon Democrat was constantly belittling and insulting them. On Oct. 10, 1855, he wrote:

Know Nothing delegates from the different townships in the county met in this place for some DARK PURPOSE, on Tuesday evening of last week, and we understand from a reliable source that six old fogy Whigs (Know Nothings) from each Township, are to meet in convention in this village sometime this week for the purpose of making nominations.

This is a great example of turning something harmless and ordinary into something ominous. Despite Bellis’ hostility, the Know Nothings were nothing to sneer at in Hunterdon County. The new party turned out to be very popular. This is because abolitionism, as advocated by the new Republican party, was seen as too radical for most of the former Whigs. Here is a list of those who moved from the Whig party to the American Party. (I have taken the American party names from a list of members of the Fillmore-Donelson Club of 1856.)

John Barber, James H. Blackwell, Henry Boss, Peter I. Clark,

Dickenson M. Cox, Samuel W. Dilts, William P. Emery,

Geo. A. Evans, Jacob F. Fisher, James J. Fisher, John E. Forman,

Wm W. Hall, Peter V. Hartpence, Jonathan Higgins,

Charles W. Holcombe, Elisha E. Holcombe,

Ferdinand S. Holcombe, John Hoppock, Edward Hunt,

Ross Jones, Isaiah P. Large, John K. Large, Levi M. Mettler,

Hiram Moore, Theodore Polhemus, Jacob S. Prall, John S. Prall,

Wm B. Prall, John P. Quick, Peter P. Quick, George A. Rea,

Runkle Rea, John G. Reading, John C. Reed, George P. Rex,

George W. Risler, Wm R. Risler, Ogden Roberson,

Ralph W. Rudebock, John Runk, Edward Schenck,

Mahlon Schenck, Joseph Servis, Wm Servis, Mahlon Smith,

Martin Smith, Nathan Stout, Charles Tomlinson,

David Williamson, John H. Williamson, Israel Wilson,

John A. Young, William W. Young.

Students of Hunterdon history will recognize many of these men as very prominent in the mid-19th century. They were merchants, lawyers, bankers, and successful farmers. I tried to find members of the Whig party who joined up with the new Republican party before 1860 with little success. Part of the problem comes from the fact that the Republican paper that was founded in 1856 did not publish lists of names the way the Gazette did. So far, the only people I have found to switch from Whig to Republican during this period were Johnson Barber, Abraham Fulper and Samuel Hill. As for switching from Whig to Democrat, those names were even scarcer—only Samuel Clark and Andrew B. Rittenhouse.

Remember all those various parties that emerged in 1854, like the Free Soil party and the Anti-Nebraska party? They were often referred to collectively as “the Opposition.” Here are some former Whigs who were identified with that party, such as it was: George A. Allen, Abraham Banghart, Lambert Boeman, Robert Foster, Samuel M. Higgins, Paul K. Hoffman, Jacob S. Manners, Nicholas E. Melick, Theodore H. Risler, Nelson Thatcher, Jonathan M. Welsted, Jacob S. Williamson, Nelson V. Young.

Nichols Joins the American Party

The earliest hint in the Gazette that Willard Nichols had turned toward the American Party was his announcement on March 21, 1855 of a new newspaper in Trenton called the New Jersey Free Press, published by E. R. Bordon. Nichols declared that the paper would be:

. . . decidedly anti-Monopoly in its character—advocating old Whig principles, without ignoring the new and important element of Americanism. [my emphasis] Those who know Mr. Borden best, speak most highly of his abilities as a journalist. We wish him the fullest success.

In the June 20, 1855 issue of the Gazette, Nichols wrote that “Slavery is a blasting curse and a political engine of dangerous power, yet we shall support this platform [of the American party] until a better one is presented.” Nichols was settling on an approach that was common at the time—to condemn slavery and at the same time condemn the efforts of abolitionists to end it. He called them abolitionists, “border ruffians” and “disunionists.” They were also labeled as sectionalists, the idea being that by advocating the end of slavery they were pushing the South to secede. Nichols ranted about Abolitionists as treasonous and irreligious, just as Adam Bellis of the Democrat did. Hubert Schmidt, in Slavery in Hunterdon, wrote of Nichols:

Nichols’s bubbling sponsorship of a faction dedicated to the exclusion and oppression of Irish immigrants and of Catholics generally does not give him much credit, and the fact that he swung over rather late, at a time when the Know-Nothings were having some successes locally elsewhere [in 1854], shows him up as an opportunist. His failure to get on the Republican bandwagon, it seems likely, was the result of failure to come to terms with local leaders of that party. It seems more than a coincidence that a new rival paper, the Hunterdon Republican, should appear just two weeks after his [Nichols’] endorsement of the Americans.

On October 17, 1855, the Gazette featured the minutes from the “American Mass Meeting” that was held two days earlier in Flemington, at which Nichols was appointed Secretary. According to Nichols,

On October 17, 1855, the Gazette featured the minutes from the “American Mass Meeting” that was held two days earlier in Flemington, at which Nichols was appointed Secretary. According to Nichols,

It is conceded on all hands, that a more respectable body of men were never assembled in Flemington, than convened at the Court House on Monday. There were between five and six hundred present, perhaps not as many as some of the more sanguine were led to suppose would be here, but when we take into consideration the fact that Monday was a good day for farmers, at home, the reason is obvious. There was exactly the right kind of material present, and great harmony and enthusiasm prevailed.

Nichols also published the Resolutions that were adopted. Resolutions relating to immigrants were:

- That whilst we believe that the people should rule and the Constitution be the supreme law of the land, that there should be no “establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof” and that emigrants should be welcomed to participate in our prosperity and liberty, we hold it to be dangerous to freedom and our country, to seek political success by the aid of any religious sect, or the combination of foreign residents.

- That the Naturalization Laws require essential amendment, and that no persons should be admitted to citizenship until they have learned to appreciate the rights and perform the duties of citizens.

- That without excluding Americanized foreigners or citizens disavowing foreign allegiance, we believe that the safety of the Republic requires that AMERICANS SHALL GOVERN AMERICA.

Resolutions concerning the extension of slavery read:

- That the passage of the Kansas Nebraska Law by the Administration [i.e., Democrat Franklin Pierce], and their support of the lawless acts perpetrated in carrying the law into execution, and the removal of Governor Reeder, have, in our opinion, revived the before-settled slavery controversy, aroused the Anti-slavery and Abolition parties of the North and the Nullifiers of the South, stirred up a Presidential issue on the Slavery question, and endangered the safety of the Union.15

- That whilst we disavow the sentiments of slavery agitators of the North and South, and hold to the constitutional rights of slave, as well as free States, we believe that the Kansas outrages should be redressed, and the Missouri compromise restored, and that all parties should unite against the wrongdoers to effect that result.

By condemning both abolitionists and proponents of the slavery system, the American Party was trying to pull in voters on both sides of the slavery issue.

In his pamphlet on slavery’s history in Hunterdon County, Hubert Schmidt wrote that during the 18th and early 19th centuries, Hunterdon residents were fairly tolerant of African Americans. They were present in limited numbers and usually lived with the families of their owners, and some very close relationships were established. But once the controversy over slavery in the territories was ignited by the Kansas-Nebraska Act, attitudes by whites in Hunterdon toward Black people turned decidedly negative. The term ‘nigger’ began to be used and degrading humor showed up in publications. Members of the Republican party, established to abolish slavery, were usually called “Black Republicans” by both Democrats and Know Nothings.

In fact, political rhetoric by newspaper editors was really heating up in the 1850s, all thanks to the controversy over allowing slavery in the new states and territories. Nichols referred to Democratic party politicians as “trimmers, wire-pullers and primers” and “mercenary hacks.” Bellis wrote of Nichols (in the issue of Oct. 24, 1855):

We really pity the menial slave that has charge of the Hunterdon Gazette, that he is compelled to edit a Know Nothing paper instead of Whig, for the reason that there is quite a large number of very respectable Whigs in the County, that would be glad to have Whig principles advocated instead of Know Nothingism.

In New Jersey, there was an election of some kind every year. In 1855, the seats in contention were State Senator and State Assemblymen. The American Party candidates that year were George W. Risler of Flemington for State Senator, and for Assembly in the 1st District, Charles A. Skillman of Lambertville; for 2nd Dist., Capt. Edward Hunt of Mt. Pleasant; for 3rd Dist. Sylvester H. Smith of Bethlehem; for 4th Dist., William R. Moore of Flemington. For Coroners: Levi Williamson, Jeremiah Todd, and Martin Smith.16

Some Known Democrats, 1857-1861

Having provided lists of the Whigs and members of the American party during the 1850s, it seems only appropriate to name some of the Democrats. In Hunterdon County there were far more Democrats than any other party, but very few lists of names appear in the Hunterdon Democrat, other than those men running for office.

Nelson Abbott, Enoch Abel, Henry Anderson, John Alpaugh,

William C. Apaugh, Philip Apgar, Henry H. Anderson,

David H. Banghart, Charles Bartolette, Wm R Bearder,

Garret Bellis, John Y. Bellis, Augustus Blackwell, Dr. John Blane,

Alexander V. Bonnell, Samuel H. Britton, William Bunn,

M. M. Burt, John H. Capner, Thomas B. Carr, Anthony L. Case,

John H. Case, Joseph B. Case, Peter I. Clark, Samuel Clark,

John C. Coon, Joseph Cornish, Ingham Coryell, George F. Crater,17

John B. Creed, Henry Crum, David Davis, Wm H. Dawes,

James W. Duckworth, David Dunham, Joseph Durham,

Wm Egbert, John R. Farlee, Zachariah Flomerfelt, Joseph Fritts,

Abraham W. Grant, Samuel Groenendycke, George Henry,

Israel Higgins, Peter C. Hoff, Jehu Hoffman, A. H. Holcomb,

Geo. B. Holcomb, Robt Holcombe, Richard Hope, E. W. C. Hough,

O. H. Huffman, Herbert Hummer, Samuel R. Huselton,

Am [Amos?] H. Johnson, Jr., Samuel Johnson, William Johnson,

John L. Jones, Robert J. Killgore, Jacob Kline, Miller Kline,

Capt. Geo. A. Kohl, John Kugler, Jacob Lake, Joseph P. Lake,

John Lambert, Andrew Lane, Garret Lare, John Lewis, Samuel Lilly,

Elijah Lott, George G. Lunger, H. R. Manners, Henry Mathews,

Elijah R. Mettler, William C. Mettler, Amos Moore, Jonas Moore,

N. C. P. Moore, Wm R. Moore, Wm S. Moore, Lemuel B. Myers,

Leonard B. Myers, Luther Opdyke, Ephraim O. Parker,

Edmund Perry, Edward G. Phillips, George Pierson,

Joseph B. Pierson, Benjamin Pursel, John C. Rafferty,

Josiah M. Reed, William Riggs, Andrew B. Rittenhouse,

John P. Rittenhouse, Charles Roberts, James S. Rockafellow,

John B. Rockafellow, John H. Rockafellow, John S. Rockafellow,

Peter Rockafellow, A. E. Sanderson, George A. Schamp,

Andrew J. Scarborough, Joseph Scarborough, Charles Sergeant,

Gershom C. Sergeant, John T. Sergeant, Wm Sergeant,

Garret Servis, John Shafer, George Shurts, Michael Shurts,

John Simerson, John Sine, Isaac Smith, Joseph C. Smith,

Mahlon Smith, S. [?] Smith, Asa Snyder, William Snyder,

Wm T. Srope, Lewis H. Staats, Henry Stothoff, Zebulon Stout,

Derrick A. Sutphin, Wm Swallow, Sr., Wm B. Swallow,

Samuel Taylor, Robert Thatcher, John R. Thompson,

William Tinsman, Aaron T. Trimmer, Henry S. Trimmer,

John D. Trimmer, Samuel Trimmer, David Van Fleet,

Andrew Vansyckel, John Vansyckel, John Voorhees,

Peter E. Voorhees, John M. Voorhis, George W. Vroom,

Henry Wanamaker, John Weller, Joseph R. Wert, James Willever,

Joseph W. Willever, Peter E. Williamson, Richard H. Wilson,

Silas Wright, William Wright, John Y. Yard, John R. Young,

and Lewis Young.

For more on Hunterdon County and the Civil War, click on Civil War under the heading Topics in the right-hand column.

The years described in this article, 1850-1855 were a prelude to the momentous presidential campaign of 1856, the first presidential campaign in which both the Republican party and the American party ran candidates. Presidential campaigns are certainly important to national history, but they are also very significant on a local level, a subject to be dealt with in my next article.

Footnotes:

- Not to be confused with the ed. of the Democrat, Adam Bellis ↩

- Hunterdon Gazette, April 13, 1853. ↩

- David I. Potter, Impending Crisis; America Before the Civil War, 1848-1861. ↩

- It is hard to say exactly when Nichols purchased the Gazette from Henry C. Buffington, since the sale of a newspaper did not get recorded the way the sale of real estate did. The issue of March 22nd was the first in which Nichols was listed as publisher and editor. ↩

- H.C. Deed Book 91 p.147, Book 113 p.355. See “A Store, A Bank, A Mansion.” ↩

- H.C. Deeds Book 135 p.13, Dickenson S. Cox to John T. Bird; Book 129 p.352, Peter Cox to Dickinson Cox; Book 117-425, Executors of Joseph H. Reading dec’d (Samuel Evans & John C. Hopewell) to Peter & Dickinson Cox. ↩

- Schmidt, Attitudes to Slavery in Hunterdon County, p.28. Much to my dismay, the Oct. 11, 25, & Nov. 1, 1854 issues of the Gazette are missing from the Hunterdon Co. Historical Society collection, so I cannot check up on Schmidt’s quote. Also missing are the issues for early June following passage of the Kansas Nebraska Act. ↩

- Many thanks to David I. Potter and his wonderful, Pulitzer-prize-winning book Impending Crisis, America Before the Civil War, 1848-1861. I also highly recommend William Gillette, Jersey Blue, Civil War Politics in New Jersey, 1854-1865. ↩

- Potter, p.248. ↩

- William Gillette, Jersey Blue, p.28. ↩

- Hubert Schmidt, “The Press in Hunterdon County, 1825-1925.” ↩

- Potter, p.248-49. ↩

- The label “Know-Nothing” is said to have originated with Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune, an outspoken abolitionist. Because the American party did not actively support abolition, Greeley had little use for them. See also “Poor Horace Greeley.” ↩

- E. T. Bush, “A State Business Directory for 1850,” published in the Hunterdon Democrat, Oct. 12, 1933. See Hunterdon Businesses in 1850. See also, Hubert G. Schmidt, The Press in Hunterdon County, pp. 28-29, “Lost Cause” and “Hunterdon Republican.” ↩

- Pres. Franklin Pierce named Andrew H. Reeder (1807-1864), born in Pennsylvania and educated at the Lawrenceville Academy, and a loyal Democrat, the first governor of the Kansas Territory in June 1854. He was governor when many Missouri residents crossed the dividing line to vote in Kansas in favor of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Reeder refused to ratify the results, so Pierce dismissed him. ↩

- Regrettably, subsequent issues for November 1855 are missing from the HCHS Collection, so we cannot say what Nichols thought about the election of 1855. I badly wanted a look at the Democrat for November 1855 to see the editor’s reaction to the election but was dismayed to find those issues are also missing from the collection. In fact, I cannot even name the winners of the election, who were most likely Democrats. ↩

- Crater, owner of the Union Hotel, was one of those men who signed up with more than one political party. He also seemed to sympathize with the Know Nothings. ↩

Ron Warrick

March 27, 2021 @ 1:39 am

Oh, dear, I hope you don’t get canceled for spelling out the n-word.

Ron Warrick

March 27, 2021 @ 1:42 am

Very interesting. You almost make the Know-Nothings sound like the moderates of their day. I shall have to investigate further.

Marfy Goodspeed

March 27, 2021 @ 8:19 am

Well, if you were Irish or German or Catholic, you probably would not feel that way. It is interesting that during this period, many of the Know Nothings were supporters of anti-slavery candidates. Even Abraham Lincoln questioned how they could support equality for African Americans but not for European immigrants.