The most recent issue of the Hunterdon Historical Newsletter (vol. 51, no. 2) includes an article by me on the Democratic Club of Delaware Township. I thought the story an important one, so, for the benefit of those who do not subscribe to the newsletter, I am also publishing it here on my website, with a couple additional notes.

(I do hope you will consider becoming a member of the Hunterdon County Historical Society, which includes a subscription to the newsletter. It’s a great way to support the preservation of Hunterdon County history. Here’s their website: Hunterdon History.)

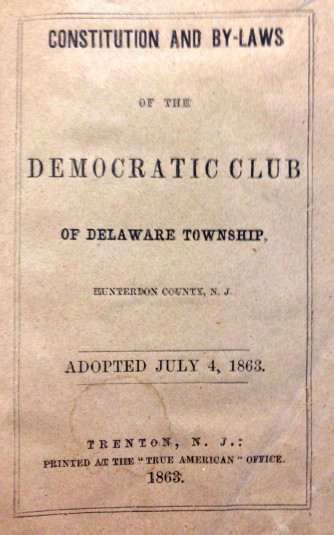

Recently I discovered in the files of the Hunterdon County Historical Society a small booklet entitled “Constitution and By-Laws of the Democratic Club of Delaware Township, Hunterdon County, N. J., Adopted July 4, 1863.” It was published at the office of the True American newspaper in Trenton.

Recently I discovered in the files of the Hunterdon County Historical Society a small booklet entitled “Constitution and By-Laws of the Democratic Club of Delaware Township, Hunterdon County, N. J., Adopted July 4, 1863.” It was published at the office of the True American newspaper in Trenton.

What a find, I thought. But, as I started reading, my eyes widened. Statements in the resolutions showed that club members saw nothing wrong with slavery, and wanted to end the Civil War by making a compromise with the southern states. Perhaps I should not have been surprised. I knew that the Democratic Party was very strong in Hunterdon County ever since Andrew Jackson ran for president in 1824, and that Abraham Lincoln was not very popular here. I also knew that Locktown was known for its “Copperheadism.” It is a subject I’ve been wanting to write about for some time. What held me back was a clear understanding of what New Jersey Democrats stood for. This booklet spells that out in no uncertain terms. If we judge these people by today’s standards, we must call them racists. But in 1863 such a term did not even exist.1 Is it fair to judge them by our standards?

The booklet began with a preamble, which read in part:

Whereas, The sad history of our beloved country during the administration of Abraham Lincoln proves that the fallacious political dogmas of the so-called Republican party are entirely adverse to, and in direct violation of, the principles upon which the Federal Republic of the United States was established ; . . . .

Then followed the Constitution setting up the workings of the club—meetings, officers, etc.—the usual. There is nothing unusual about the By-Laws either, except perhaps for Article III, Section 1:

Any white male inhabitant of the township of Delaware, above the age of eighteen years, may become a member of this Club, by signing the Constitution, and paying the sum of ten cents into the Treasury, upon which he shall receive the badge of the Club ; provided, that where an objection is urged against the applicant for membership, a vote shall be taken to decide the question.

A hint of things to come. The By-Laws were followed by this statement:

On motion of General Sergeant the Preamble and Resolutions adopted March 3d last were re-endorsed, and ordered to be attached to the Constitution and By-Laws as part of the platform of the Club.

“General Sergeant” was not a duplication of titles. John T. Sergeant of Sand Brook was General of the Hunterdon Brigade of militia and of the Delaware Guards.

The Preamble to the Resolutions, adopted on March 3, 1863, and “re-endorsed” on July 4th, read:

Whereas, the right peaceably to assemble to discuss the acts of public men, and to express our opinions in regard to their measures, is guaranteed to us by the first article to the Amendments to the Constitution of the United States, and believing that a failure to do so, in the present crisis of our country’s history, would be criminal on our part ;

And Whereas, we believe that the rapidly developing plot of Black Republican usurpation (as developed in the unconstitutional and revolutionary scheme of centralizing the powers of the government in the hands of a President who, by his arbitrary and tyrannical assumptions of authority, has already forfeited our confidence,) is a start[l]ing admonition to all true patriots that the liberties secured by our fathers are in danger . . .

“Black Republican” was a term used by Democrats to besmirch the newly-created Republican Party with the notion that they intended not only to free the slaves, but to allow unheard of civil liberties to black Americans, even to the extent of promoting intermarriage. Another derogatory term used by Democrats for the Republican Party was “the Abolition Party.” Such an attitude would carry no weight today, but was a very effective argument back in 1863. Recall that on January 1, 1863 the Emancipation Proclamation was signed. For us today, it was a great moment in American history, but many of the Democrats of 1863 thought it was a disaster.

The preamble was followed by nine resolutions.

1. Resolved, That while we will, as heretofore, give our cheerful aid and support to the Government of the United States in all its constitutional and legal acts, at the same time we enter our most solemn protest against those unconstitutional and destructive measures instituted by the present Administration, which, while they have divided the people of the North, have united all classes at the South ; and believing that “resistance to tyrants is obedience to God,” we will use all proper means which he has given us to oppose their execution.

2. Resolved, That among these unconstitutional acts we recognize : arrests of our citizens without legal process ; the suspension of the write of habeas corpus ; the emancipation proclamation ; the appropriation of the money belonging to the people of one State to pay for slaves emancipated in another ; and last, though not least, that abominable and tyrannical conscription act recently passed by Congress, which places the life and liberty of every man, woman and child at the caprice of a set of contemptible pimps and spies, called provost marshals, and their deputies ; and that we cannot permit our most sacred rights, as citizens of a sovereign State, to be thus trampled in the dust without an entire repudiation of our manhood.

Here I must say they had a point. Some fundamental rights had been abridged by President Lincoln in response to the pressures of war, like suspension of habeas corpus. And they were probably right in stating that the North was divided while the South was united by not only the actions of President Lincoln, but also by his very election. In the 1860 Democratic Convention, the party was split on the issues of slavery and states’ rights. Many (but certainly not all) Northern Democrats opposed expansion of slavery into the western states. Southern Democrats were united in demanding it.

In last week’s post, Benjamin H. Ellicott wrote about the Civil War in his diary of 1862. In his opinion, the Emancipation Proclamation would permit “the U. S. Government to enter into the wholesale Negro trade,” in which the government would purchase the freedom of slaves from their masters in the secession states. He thought the Proclamation gave comfort to Lincoln’s opponents, rather than helped to end the war. As these resolutions show, he was not alone in thinking that.

Concerning “the appropriation of the money belonging to the people of one State to pay for slaves emancipated in another,” President Lincoln had asked Congress to pass a law allowing for gradual and compensated emancipation in four border states. When slavery was abolished in the District of Columbia, the slaveholders were compensated, with federal tax dollars, of course.

Concerning those “contemptible pimps and spies, called provost marshals, and their deputies,” these were officials created by “the Enrollment Act” of March 1863, also known as “The Civil War Military Draft Act.” It required that every adult male citizen between the ages of 20 and 45 be enrolled for the draft. The provost marshals and their deputies were responsible for identifying these men and making sure they were enrolled.

3. Resolved, That the present unhappy and sanguinary war (commenced ostensibly for the restoration of the Union, the support of the Constitution, and the maintenance of the integrity of the Government established under it) is manifestly a contest for the emancipation of the so-called “slave,” and the equalization of the black with the white race, and in our opinion, ought to cease, and that negotiation should be entered into for the restoration of the Union upon such principles as would be alike honorable to all sections.

That reference to the “so-called ‘slave’” is odd. How could a slave be so-called? A slave was a slave. But, the words “slave” and “slavery” never appear in the Constitution, even though there are several provisions concerning that subject. It apparently was an uncomfortable word to use, even for those who supported slavery.

The real concern of these club members was “the equalization of the black with the white race.” That being the case, how could there be any principles that “would be alike honorable to all sections”?

4. Resolved, That to our gallant sons and brothers in the field we tender our hearty thanks for the brave manner in which they have performed their duties, and our sympathy for the sufferings they have endured, and that we will welcome their speedy return to our midst with heartfelt joy and gratitude.

Here we have the traditional American attitude toward the men who wear their country’s uniform. No matter what the purpose of the war they were sent to fight, admiration and gratitude for their service was the one thing New Jerseyans could agree on.

5. Resolved, That the principles and views enunciated by our Governor, Joel Parker, in his inaugural address, have inspired us with confidence in our Chief Magistrate, and we hereby pledge him our continued and earnest support, so long as he adheres to the course therein marked out.

Gov. Parker was a unifier of the Democratic Party. He won his election in 1862 by taking the middle road between the radicals known as Copperheads or Peace Democrats, and the regular or “War” Democrats. The radicals thought the South was entitled to secede, and therefore all attempts to stop it were unconstitutional. They claimed the North was entirely responsible for the war. Regular Democrats, including Gov. Parker, supported a legitimate war effort, but condemned ‘unconstitutional’ acts of government. They opposed secession as much as they opposed abolition. This was the larger group to which the Delaware Township Democrats seem to have belonged.

After his election Gov. Parker’s ‘middle road’ involved supporting the call for Union troops and prosecution of the war, while at the same time opposing Lincoln’s policies. His motto was “The Union as it was, the Constitution as it is.” This policy explains why the Delaware Township Democrats hedged their endorsement of him.2

6. Resolved, That we approve and endorse the Peace Resolutions now before our State Legislature, hoping that they may be “the beginning of the end,” sought to be accomplished.

The “Peace Resolutions” were passed by the majority Democratic NJ Legislature and signed by Gov. Parker on March 24, 1863, calling on the Federal Government to appoint commissioners to negotiate with commissioners from the southern states for an end to the war, on the basis that the war should never have been started in the first place and that the Federal government had overstepped constitutional bounds by emancipating the slaves. Nothing came of these Resolutions.

7. Resolved, That the short, but brilliant, career of Hon. James W. Wall, in the Senate of the United States, has been alike honorable to himself, useful to his State, and satisfactory to his constituents, and that we call upon him to bide his time, assuring him that his name is held in warm remembrance by the friends of constitutional liberty, who will not fail, in due time, to reward him ; that we fully endorse the nomination of Hon. William Wright, of Essex, for the United States Senate, in whose integrity and love of constitutional democracy we have the most implicit confidence.

James W. Wall was one of the most outspoken, hot-headed opponents of the war, publishing his views in newspapers and in speeches. U. S. Marshalls arrested him in 1861 and kept him in prison for two weeks without pressing charges. They released him after he pledged allegiance to the Union, thereby creating a martyr to the cause of the Peace Democrats. In early 1863 when the legislature was considering the Peace Resolutions, Wall was elected to fill a vacant U. S. Senate seat. But in March 1863 he failed to be re-elected.

8. Resolved, That we hold abolitionism and secession to be rank political heresies—the last the offspring of the first,–and that while we abhor and detest the one for its pusillanimous attacks upon the principles of our government, we protest against and condemn the other for its equally seditious, though more open and manly course.

In other words, abolitionism brought about secession. How one could see abolitionism as a “pusillanimous attack” on the principles of the American government is hard to understand, unless one believes that by refusing to overturn slavery, the Framers were in fact endorsing it. And the idea that abolitionism was not “manly” seems preposterous, unless you believe that secessionists were willing to risk everything for their principles while abolitionists were not.

The last resolution gets to the crux of their fears.

9. Resolved, That we urge upon our representatives in the State Legislature the importance of any measure that will prevent the influx of negroes into our State, and that we request the passage of a law to obviate such mischievous intention ; and that we protest against the payment by our State of any portion of the appropriation for the emancipation of slaves, and that we desire such legislation as will protect us from all unconstitutional expenditure of our money.

Slavery was the most potent issue working in the favor of the Democratic Party. One of the most compelling reasons not to end slavery was to keep “negroes” in the south, away from northern communities. Democrats claimed that the cheap labor provided by newly freed slaves would destroy the labor market for white men in the North. The other fear was the threat of mixing the races. For white men who could not imagine black men living as their equals, this was a nightmare.

Ironically, there were 43 African-Americans living in Delaware Township in 1860. I cannot say if any of these people were still slaves—the 1860 census does not identify slaves. However, anyone under the age of 56 was free, since the Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery, passed in 1804, stated that all those born after that year would be freed on reaching maturity. None of the people identified as black were living with any of the officers of the Democratic Club.

There were six independent black families headed by Lorenzo Williams, Jeremiah Williams, Prime Lambert, Sanfred Farley, Peter Jackson and Charles Wilson. Two of Peter Jackson’s children were living with other (white) families. Daniel Williams, age 70, and possibly related to Lorenzo and Jeremiah Williams, was living with Joseph G. Bowne, as was also Mary E. Stout, age 22. Clara Dickason age 57 and Westley Barber age 13 were living with Wm. Barber. Robt Waterhouse lived in the house of Ingham Waterhouse, Isaac Fox age 19 with Josiah Holcombe, and Mary E. Coal age 14 lived with John Runkle. Frank Conover age 52 was living in the poor house run by Jacob Lake.

And now I must ask: Who were these people so devoted to the Democratic principles of 1863? Were they scoundrels and misfits? Not at all. They were pillars of the community, men who were widely respected. The initial officers of the club were listed on the first page of their booklet. The By-Laws required that there be one president and as many vice-presidents as there were school districts serving the Township of Delaware. Here is the list of officers:

President, Joshua Primmer; Treasurer, Dr. I . S. Cramer; Secretary, Dr. H. B. Nightingale.

Vice Presidents: J. V. C. Barber, David B. Boss, Esq., John M. Bowne, Henry Crum, John Fisher, E. M. Heath, Bateman Hockenbury, J. M. Hoppock, Isaac Horne, A. B. Rittenhouse, Gen. J. T. Sergeant, Rev. Henry F. Trout, Jos. Williamson.

The members of the Delaware Township Democratic Club, acting on what they considered the highest principles, came together to prevent black Americans from becoming citizens and members of society, at least in their neighborhood. Egbert T. Bush, respected schoolmaster and author, was a young boy during this time, and looking back on it wrote, “In those mad days of prejudice and passion, who, on either side of the controversy, was listening to reason?” Despite the professed wishes of the Democratic Club’s manifesto, no one in those days could sit down and reason with their opponents.

I want to thank the trustees of the Hunterdon County Historical Society for agreeing to publish this article, for recognizing the importance of looking at our history without blinders, and for acknowledging what has happened in the past—the good and the bad—so that we can learn from it.

Footnotes:

- The word was first used in 1902 to describe prejudice against American Indians. ↩

- For a reliable portrait of Gov. Parker, see The Governors of New Jersey, Biographical Essays, revised edition, edited by Michael Birkner, Donald Linsky and Peter Mickulas, Rutgers University Press, 2014, pp. 172-176. ↩

Deb R

June 6, 2015 @ 12:38 am

Thanks for yet another great article. Some modern day historians believe that the Civil War wasn’t really about freeing the slaves, but instead was used as an excuse by the North in order to garner support for it–in order to economically dominate the South. That’s why abolitionism would be, in the following paragraph, considered pusillanimous, or cowardly, and why secession was stated as being the more manly of the two heresies. In other words, the North was using a chick–sh– of an excuse for going to war and the South, at the very least, was being up front and honest or “manly” in their reasoning for wanting to secede. That’s my take on that paragraph, anyway. So maybe this document helps prove that theory.

“That we hold abolitionism and secession to be rank political heresies—the last the offspring of the first,–and that while we abhor and detest the one for its pusillanimous attacks upon the principles of our government, we protest against and condemn the other for its equally seditious, though more open and manly course”.

Ron Warrick

June 7, 2015 @ 1:09 pm

The date of July 4, 1863 is the day after the Battle of Gettysburg. As I understand it, this would have been a time of the highest anxiety, if not outright panic, in the North over the outcome of the war, as had Lee won at Gettysburg, Philadelphia and Washington were in his sights. The fact that Lee’s army escaped from Gettysburg meant the war would drag on.

Marfy Goodspeed

June 7, 2015 @ 1:16 pm

Actually, Ron, I did not mention in the story that the Democrats of Delaware Township had already begun organizing and initially adopted their resolutions on March 3, 1863, and readopted them on July 4th. But your point about anxiety in the North about the war is certainly valid.

Janice Armstrong

June 8, 2015 @ 7:09 am

I had just read your article about the Democratic Club of Delaware Township. This week I attended the NJ Historic Preservation Conference and both the opening and closing speakers talked about historic sites handling uncomfortable parts of their history. One speaker was Ruth Abram, who founded the Tenement Museum in NYC and the other was Elizabeth Silkes who is Executive Director of The International Sites of Conscience.

Your article in the HCHS newsletter probably made some people uncomfortable but I think it was very timely. We know that all US history is not about rich white guys but in this case it was and they behaved badly!!

Marfy Goodspeed

March 20, 2016 @ 9:21 am

NJ Civil War historian Joseph Bilby posted an interesting biography of James Walter Wall on his Facebook page on March 20, 2016. It included this:

“Following the death of New Jersey U.S. Senator John R. Thomson in office in 1863, Wall was elected by the state’s legislature to fill out the six-week remainder of Thomson’s term, even though his extremism did not reflect the mainstream party view. In a speech in Philadelphia on his way to Washington, Wall told his audience that he was going to fight for “those great principles of liberty…which are embodied in the amendments to the Constitution of the United States, every one of which, I am sorry to say, has been trampled under foot by the present Administration.”

Dismissing the moral aspect of human slavery, Wall, like many Copperheads, chose to characterize it as a local private-property issue viewed through a lens of inherently racist assumptions. During his brief tenure, he posited in a speech on the senate floor that abolition would result in “a white nation, which lost its liberties and its name in endeavoring to give freedom to the black and inferior race.””