On November 18, 1896, two gentlemen from East Amwell Township announced in the Hunterdon Republican newspaper that they would petition the state legislature to change the boundary between East Amwell and Delaware Townships. It was a fairly radical change they were proposing, in which Delaware Township yielded to East Amwell a large chunk from its eastern border and Delaware got nothing in return. On April 17, 1897, the State Legislature followed through and passed a bill to make that happen.

Perhaps East Amwell wanted more land to surround Ringoes village. But there is also reason to think there was a political motivation, inasmuch as the petitioners for the change, William H. Manners and Simpson S. Stout, were firm Republicans, and Delaware Township was reliably Democratic. It seemed like such a radical change that I began looking for the rationale behind it.

This was not the first time that proposals were made to shrink the size of Delaware Township. It had happened three times before. The first was a very minor change, when a small part of Delaware at Ringoes was ceded to East Amwell in 1854.

Lincoln Township

The second instance was actually intended to divide Delaware Township in half. On February 28, 1866, less than a year after the murder of Abraham Lincoln, the Hunterdon Gazette published the following:

On Wednesday, in the Senate, . . . A petition was presented by Mr. Ludlum from the citizens of Delaware, Hunterdon Co., asking that the township of Lincoln be set off from that township.

The petition for that bill may be hiding somewhere in a state archive, but I have not discovered yet whether it was saved. Apparently very few legislative papers were archived in the 19th century after 1844. It would have been so interesting to know who signed the petition.

Senate Bill 60

The Gazette was correct that Mr. Ludlam had presented a petition from citizens of Delaware Township to the Senate, which he did on February 21st.1 But it was Senator Richey of Mercer County who introduced the bill a month earlier, on January 23, 1866.

“Mr. Richey, on leave, introduced Senate bill, No. 60, entitled An act to set off from the township of Delaware, in the county of Hunterdon, a new township, to be called the township of Lincoln, which was read for the first time by its title, ordered to have a second reading, and referred to the Committee on Municipal Corporations.”2

Although Augustus G. Richey (1819-1894) was a successful lawyer living in Trenton, he spent his early years in Flemington before setting up his law practice. According to James P. Snell,

“Hon. Augustus G. Richey, another member of the Trenton bar, was prepared for his profession in Hunterdon County, in the office of Col. James N. Reading, Flemington, and in 1844 selected his wife from among Hunterdon’s fair daughters, Annie G., eldest daughter of Hon. Isaac G. Farley.”3

In January 1866, the shock of Lincoln’s death, only seven months earlier had probably not worn off yet, so it is easy to see that Richey, Ludlam and other Republicans would be happy to set up a township in New Jersey named in Lincoln’s honor. But why that particular place? Probably because Delaware was the only township to make this request, being split as it was between Union supporters and Copperheads.

In 1866, Delaware Township included Stockton, a developing commercial and manufacturing area (Stockton did not become an independent Borough until 1898), thanks to the D&R Canal, established 1834, and the Belvidere-Delaware Railroad, established 1851. Perhaps this exposure to outside influences made residents in that area more sympathetic to the Union cause during the Civil War. There is clear evidence that people in the northern part of the township were decidedly of a different mind-set. During the War, “Copperheadism” was pretty widespread around Croton and Locktown (see “Copperheadism” in Locktown and Democratic Club of Delaware Township).

As an illustration of how intense people’s feelings were, there is this item from Egbert T. Bush who wrote about John Bellis of Kingwood. Bellis kept a store at Locktown during the Civil War and was

an ardent Republican, while his surroundings were quite as ardently something else. Things grew so warm that some of the “hot heads” thought it would benefit the country if they could “scare a little sense into the head of that radical.” So they actually dug a grave and let it “leak out” who was to be the occupant. But John did not scare “worth a cent.”4

Given that frame of mind, it seems most unlikely that the petition came from northern Delaware Township.

But the prospects for passage of the bill were not good. The Senate of 1866 held 12 Democrats and only 9 Republicans.5 And Democrats seemed much fonder of Andrew Johnson than they did of Abraham Lincoln. On the same day that Sen. Richey introduced Bill 60, resolutions were offered in the Assembly and Senate to endorse “the action of President Johnson in vetoing the Freedmen’s Bureau bill.” The State Senate’s version declared that “the thanks of the nation [are] due to him for his constant effort to secure an undivided Union.”6

So, on January 23, Senate bill 60 was read, ordered to have a second reading, and referred to the Committee on Municipal Corporations. The next day Amos Robins, Democrat of Middlesex and chairman of that committee, reported the bill out, without amendment. On February 14th, the bill was given its second reading, at which time “Mr. Wurts presented a remonstrance from citizens of Delaware township, Hunterdon county against the passage of said bill, which was read. On motion of Mr. Wurts, the bill was postponed for the present.”7

When the Democrat-leaning Gazette announced introduction of the bill on February 28th, it also made this observation:

“The bill to set off from Delaware twp., in this county, a new township to be called Lincoln was postponed. Mr. Wurts presented several remonstrances against the bill [the Senate Journal only mentioned one] and spoke against it, and Mr. Richey defended it—the contest between the two gentlemen becoming almost personal.”

Alexander Wurts was the State Senator representing Hunterdon County, and a very strong Democrat. He was also a lawyer, and he and Sen. Richey from Mercer County frequently appeared in court together, sometimes on the same side, but just as often on opposite sides of a case. They were well-accustomed to debating each other. But even though they probably enjoyed the give and take of a debate, it seems that in this instance it became a little more intense than was usual between the two men.

What the Gazette did not mention was that on February 21st, a week after Wurts got the bill postponed, Sen. Richey presented a petition from “citizens of Delaware Township” in favor of the new township. In addition, Sen. Benjamin Buckley, Republican of Passaic County, also presented a petition from Delaware Twp. citizens asking for the new township. Both petitions were “read and laid on the table.” The fact that two Republican Senators had to present petitions from citizens who lived outside their county, and that those citizens could not get the support of their own Senator, a Democrat, makes it clear to me that this was a party issue.

The next day, Senate Bill 60 was “taken up,” but it was lunchtime, so the Senate adjourned. They returned at 3:00 p.m., but nothing more was said about the bill that day.

The Bill’s Fate

On March 6, 1866, Senate Bill No. 60 was taken up and read a third time. It was finally time to vote on the bill.

Given the number of Democratic and Republican Senators, the outcome was pretty well foreseen. Eight Senators voted aye, mostly Republicans with the addition of two Democrats, Cobb of Morris County and Reeves of Gloucester County. Twelve Senators voted nay, including Republicans Acton of Salem County, Buckley of Passaic County and Wright of Burlington County. Obviously Sen. Wurts voted against it as did the Senators from the Democratic counties of Warren and Sussex.8 I was surprised to see that Buckley, who had presented that petition from Delaware citizens, ended up voting against the bill.

Democratic dominance of the State Senate was not to last, but even after the Republicans took control, this bill was never offered again, and there were no more attempts to shrink the size of Delaware Township until 1896.

From Delaware to West Amwell

The original boundary line between West Amwell and Delaware Township began at the Delaware River north of Lambertville where the Alexauken Creek enters it, then ran northeast along the Alexauken to its intersection with the Old York Road, near Bowne Station, then along the York Road to Ringoes.

On February 12, 1896, Senator William H. Skirm, Republican of Mercer County, introduced Senate Bill 111, titled “An act to change the boundary line between the townships of West Amwell and Delaware, in the county of Hunterdon.”9 The proposed change was to move the line to coincide with the route of the Flemington Transportation and Railroad Company, today known as the Black River & Western Railroad, which parallels the creek for quite a distance.10 Along that stretch, the Alexauken Creek crossed the rail line more than once.

The bill stated that the boundary line change was to begin at the Alexauken Creek and the railroad “at the first crossing of said creek by said railroad above Lambertville,” then to follow the middle of the line of the railroad to Boss Road, then to follow the road (in the middle) to its intersection with the road from Lambertville to Ringoes “known as the Old York road,” and there to end. Everything south and east of that line that was formerly in Delaware Township became part of West Amwell, and a little bit of West Amwell got transferred to Delaware Township.

When the bill was read a third time, 16 Senators voted for it, and only three against, all of whom were Democrats, including Sen. Richard S. Kuhl of Hunterdon County.

Richard S. Kuhl, Esq.

Richard Sutphin Kuhl, Esq. (1839-1917) was the son of Leonard P. Kuhl and Dorothy Ten Eyck Sutphin of Raritan Township. Leonard Kuhl died in 1857 when his son Richard was 18. Three years later, Richard entered the law office of Benjamin Vansyckel to study law. As it happened, Vansyckel began his study of law in the office of Alexander Wurts. Despite being born lame (his draft registration of 1863 stated that one leg was six inches shorter than the other), Richard S. Kuhl became a prominent lawyer in Flemington.

In 1866, as administrator of his father’s estate, he settled the estate in the Orphans Court. Shortly afterward, he purchased a lot at 21 Mine Street (the deed described it as “the street to the mines”) in Flemington from Edmund & Elizabeth Perry.11 Even though the farm of his father Leonard Kuhl remained for a time in the family, the widow Dorothy Kuhl moved to the Flemington lot with son Richard and daughters Martha Kuhl and Henrietta Boeman.12 Both Richard S. Kuhl and Martha Kuhl never married.

Richard S. Kuhl qualified as a counsellor at law in 1867, but he was also an active investor in real estate. He was a Republican and participated in Republican party politics, up until 1883 when he was one of three elected “at the Democratic primary meeting on Saturday, as delegates to represent Raritan Tp., at the State Convention at Trenton.” Perhaps Kuhl was disenchanted with the way Republicans were dealing with the South. More likely, that was the only way to get elected in Hunterdon County.

In 1891, he was a candidate in the Democratic primary for State Senator. But he was not supported by “Boss Pidcock,” who threw his weight behind William H. Martin of Frenchtown. (I’ll have more to say about Pidcock later.)

Perhaps this experience soured Kuhl on Democratic politics. In August 1892 he got involved with a Cleveland and Stevenson Club13 that was organized by Republicans. But in 1894, he was again a candidate for the Democratic nomination for State Senator, running against Frederick U. Philhower and Lawrence H. Trimmer. This time he won not only the nomination, but also the election in November. The successful Assembly candidates were Charles N. Reading, a Republican, and William C. Alpaugh, a Democrat.

Bill No. 111 in the Assembly

On February 26, 1896, Senate Bill No. 111 was sent to the Assembly for its concurrence.14 When the bill came up for first reading two days later, the motion “was laid over until Monday night.” According to the minutes, on Monday,

“Mr. Walling offered the following resolution, which was read and adopted: “Resolved, That the Senate be requested to transmit to the House, in compliance with the joint rules of the Senate and House, all papers and documents in its possession, if any, relating to Senate Bill No. 111, and particularly the proofs relating to the publication of the notice of intention to apply for the passage of said bill required by the laws of this state.”

“Mr. Walling” was Alfred Walling, Jr., a Democrat from Monmouth County. This may have been a delaying tactic, because the Democrats did not like the bill, as you will see. As for that “notice of intention,” I do not know where it was published. It certainly did not appear in the Hunterdon Republican. Perhaps it was in one of the Trenton papers.

The bill was “taken up on second reading” on March 3rd, and given a third reading on March 4th. But instead of a vote on the bill, it was “laid over” again. The next day, David Lawshe, the representative from Hunterdon County (also a Democrat, and, as it happens, a resident of Delaware Township) presented a remonstrance from the citizens and tax-payers of the township of Delaware, who

do hereby earnestly remonstrate against such division as aforesaid, and ask your Honorable Body to leave the boundary the same as it is at present, which was numerously signed.15

It appears that the remonstrance did not move anyone to change their vote. The bill passed 36 to 13.16 (Remember, this was in the Republican Assembly, not in the Senate.) I checked to see the party affiliation of those voting nay, and found that all the negatives were Democrats, starting with the two representatives from Hunterdon County, William C. Alpaugh and David Lawshe, plus the two from Warren County, six from Hudson County, and one each from Atlantic, Burlington and Monmouth (including Rep. Walling).

So the bill was sent back to the Senate, which received it on March 6th.17 From there it went to the Governor’s desk, but Governor Griggs did not sign it. According to the Trenton Times, it was “filed without approval,” because it was “opposed on its passage in the Senate by the Democrats and was afterward made a caucus measure by the House Republicans.”18

This reason for not signing it surprises me because Gov. John W. Griggs was himself a Republican. But it does explain all the times that the bill was “laid over.” There must have been some negotiating going on in the background. Why the Democrats would have been so opposed also remains a mystery to me, since so little territory was involved. If the governor really opposed the bill he would have vetoed it. It appears that by not signing it he was trying to stay on the good side of the Senate Democrats.19

Why change the boundary? One might think it was because of the railroad, but that line had been in existence for 42 years, since 1854 when it was built as a branch of the Belvidere-Delaware Railroad.20 Even so, it is likely that the railroad wanted the change since the measure was supported by Republicans, and of course, railroad companies had a lot of influence in Trenton. Perhaps the original bill stated a reason for the change, but I have not seen it.

Whatever the reason, the change took effect by the end of March, 1896. Perhaps it was this accomplishment that made the Republicans look for other opportunities to shrink the size of Delaware Township.

East Amwell Grows

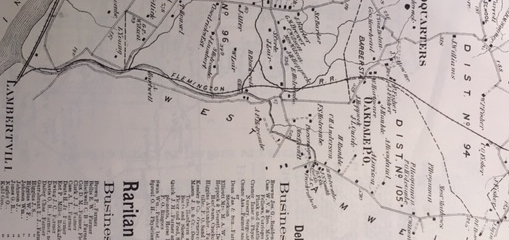

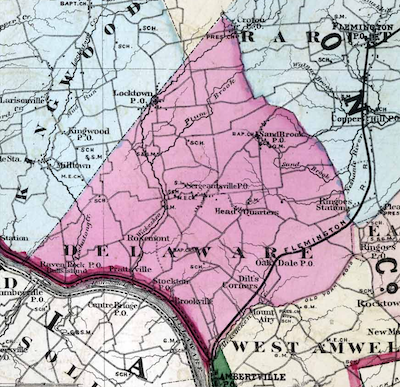

Here is a picture of old Delaware Township (from the 1872 Topographical Map of Hunterdon County, p. 82).

As I mentioned at the start of this article, toward the end of 1896, after the Presidential election of that year, two East Amwell Republicans proposed taking a large part of Delaware Township and adding it to East Amwell. I had also mentioned this change in my article on the Haines Farm (Haines Farm, part two), since that property was one of several that were affected.

Originally, Delaware Township extended all the way to the center of the Village of Ringoes. That was how Delaware Township was delineated when Delaware and Raritan Townships were separated from the rest of Amwell Township in 1838. In 1846, what was left of Amwell was divided into East and West Amwell Townships, and in 1854, a small piece of land on the west side of Ringoes was taken from Delaware Township and given to East Amwell.

Manners and Stout were petitioning to have the area bounded on the north by Dunkard Church Road, on the west by Haines Road and Wagner Road, and on the south and east partly by the railroad and partly by Old York Road. What made them think that the Legislature would agree to this? Simply the fact that the Governor was Republican and Republicans were in the majority in both houses of the Legislature.21

Party Politics in New Jersey

The presidential election of 1896 was a very important one for Republicans in New Jersey. Grover Cleveland, at one time a popular Democrat who was disgraced by the Panic of 1893, was not running for reelection. The Republican candidates were William McKinley and his running mate Garret A. Hobart of New Jersey, who had managed the campaign of John Griggs for governor in 1895 and was able to persuade New Jersey’s delegates at the Republican convention to support McKinley. The Democrats in the race (and also the candidates of the People’s and the Silver Parties) were William Jennings Bryan and Arthur Sewall (unless you were voting for the Populist Party, in which case the was vice-presidential candidate was Thomas E. Wilson). Bryan was a very controversial figure.22 When the vote was taken on November 3, 1896, McKinley had won 271 to 176 electoral votes. His success, and the presence of Garret Hobart on the ticket, probably contributed to the success of the Republicans in the legislative election.

It may be that New Jersey had already soured on Democrats in 1895 when the state elected the first Republican governor (John W. Griggs) since Marcus Ward in 1866. Republicans had held majorities in both house of the legislature a few times since the Civil War, but without a Republican governor they were limited in what they could accomplish.

As a result of the 1896 election, the dominance of the Republicans in the legislature was overwhelming; the State Senate got 18 Republicans and only 3 Democrats, and the Assembly got 53 Republicans and 7 Democrats, plus one Independent. In the next year’s election, the balance in the NJ Assembly tipped even further in favor of Republicans—56 to 4.23

So, in 1896, the governor and both houses of the legislature were in the hands of the Republican party. The time was right for any measure that would help Republicans hold on to their majorities.

Party Politics in Hunterdon County

As was the case in 1866, so it was in Hunterdon County in 1896. After 30 years, the Democratic Party still dominated the county.

The Union cause had done much to tilt the State of New Jersey toward the Republicans, but there were hold-outs where sympathies with the issue of states’ rights remained strong, and sympathy with abolitionists was not. Those counties were Sussex, Warren, Hunterdon, Cape May and some of Hudson.

Hunterdon County had long been heavily Democratic, from well before the Civil War. However, it should be noted that the county had a sufficient number of Republicans to support a newspaper. “The Hunterdon Republican” was established in 1856, while “The Hunterdon Democrat” had been in business since 1838.

In Hunterdon County, James Nelson Pidcock (1836-1899) of Readington Township emerged in the 1870s as a very powerful party boss, someone who could influence elections so successfully that no candidate was likely to win without his backing. We can rest assured that within the Democratic Party, the candidates nominated for office were the ones that Pidcock had endorsed.

This power was still effective in 1891 when Richard S. Kuhl was not Pidcock’s candidate, and therefore lost. Here is the Hunterdon Republican’s take on the convention, published on Oct 14, 1891.

Boss Pidcock’s Convention. The Democratic Convention held on 12 Oct. 1891. was boisterous and disorderly and a good deal of bad feeling was exhibited, but the Boss [James N. Pidcock] had control and his ticket was put through according to the pre-arranged program. William H. Martin of Frenchtown, was nominated for Senator. The other candidates before the Convention were Richard S. Kuhl of Flemington and James H. Willever of Bloomsbury. Mr. Martin received a majority on the first ballot.

Pidcock had served in the State Senate in 1877-79, and was elected to Congress in 1884 and again in 1886. However, by the 1890s, his influence was beginning to fade. This was seen in an item in the Trenton Evening Times of 1894:

“A little over a fortnight ago, James Nelson Pidcock, a Hunterdon county Democratic politician, who recently failed in business, came to Trenton and tried to establish commercial relations with both the Democratic and Republican camps. The newspaper correspondents learned of it and gave Mr. Pidcock so much notoriety that he went back to his home in White House and has not been to Trenton since.”24

In the Hunterdon election for members of the State Legislature in November 1896 (for the 1897 session), the Republican candidates were Capt. John Shields of Flemington for Senate, and Charles N. Reading of Frenchtown and William G. Simpson of High Bridge for Assembly. The only towns that voted for the Republican candidates were Clinton Town, Lambertville’s 3d ward, and the west district of Lebanon Township. The incumbent Democrats (Richard S. Kuhl for Senate and David Lawshe of Delaware Twp. for Assembly) won all the rest. Also winning was the other Democratic candidate for Assembly, George F. Martens, Jr. of Tewksbury. The previous Lawshe running mate, William Alpaugh, did not run again. The Prohibition candidates got a small fraction of the vote. (I found it noteworthy that they did much better in the north district of Delaware Township than they did in the south.)

David Lawshe

David Lawshe (1844-1901) served in the Assembly for three years, 1896 through 1898. He got off to a rough start in life. His father, David M. Lawshe, died just four months before David was born. David M. Lawshe was the son of Henry Lawshe and Mary Moore. David Jr’s mother, Elizabeth Ann Hice, was the daughter of Jacob Hice and Ruth Moore. For those familiar with these names, it is clear that the Lawshes had a strong connection with the neighborhood I have been writing about lately (Sandbrook, Headquarters). Just to add interest, in 1868, when David was 24 years old, his mother married a second time. Her new husband was none other than Cyrus Vandolah of Sandy Ridge.

On November 10, 1870, David Lawshe married Sarah Elizabeth Fisher (1848-1930), daughter of Johnson Fisher and Anna Gearhart. Like David, Sarah’s father also died young. After the wedding, the Lawshe’s settled in the Village of Stockton. They only had one child, Mary Belle Lawshe (c.1875-1963), who married Henry Harrison Morgan of Lambertville about 1915. Morgan’s parents had come to Hunterdon County from Ireland.

David Lawshe appears to have had little interest in farming. He went to Trenton Business College, then worked as a clerk in Fisher’s hardware store in Lambertville and became manager there in 1879.25 He got involved in local politics in the 1880s, and in 1895 was nominated by the Democratic Convention for the Assembly along with William C. Alpaugh, and Richard S. Kuhl for Senate. Of course, they won.

At some point, Lawshe had invested in the handle factory at Stockton. He was running the operation on November 8, 1896 when Stockton was hit hard by a terrible fire.26 Deed records show that at the time of the fire, the property was owned by Flemington National Bank, which had acquired it from Sylvester Cooley on April 13, 1896. After the fire, on Dec. 30, 1896, the Bank sold the “Stockton Spoke & Wheel Works” to Lawshe.27

After retiring from the Assembly, Lawshe returned to Stockton and continued to run the Spoke Works there. Clearly he must have done some serious rebuilding. He was only 56 when he died in 1901. He and his wife were buried in the Mount Hope Cemetery in Lambertville.

Back to the election of 1896

In the election of 1896, Lawshe got 178 votes in the north district of Delaware Township and 186 in the south, while the other Democratic candidate, George F. Martens, Jr., beat Lawshe in the north, getting 185 votes, but lost significantly in the south with only 168 votes.

East Amwell favored Lawshe with 186 votes and Martens with 185. But the Republicans each got 160 votes, which was a far closer margin than in Delaware Township, so it’s fair to say that East Amwell was considerably more Republican than Delaware was, but not enough to elect candidates.

As for the Board of Freeholders, it was dominated by Democrats, as one might expect. In the election of 1894, there were 14 Democrats and only 6 Republicans. The Freeholder from East Amwell that year was David Y. Ewing, a Democrat. But he was replaced in 1895 by Dr. Jacob Dilts, Jr., a Republican, indicating a shift in East Amwell toward the Republican party at that time.

That will have to be enough for now. Part Two will describe the two Republicans from East Amwell, Manners and Stout, who petitioned the Legislature in 1896, and then what happened to the bill that was introduced as Senate Bill No. 147. I will also take a look at the land in dispute and the people living there.

Footnotes:

- Providence Ludlam (aka “Provie”) was born in 1819 and resided in Bridgeton, Cumberland County. He ran once for the Assembly in 1856 but was defeated by the Democratic candidate. However, in 1862, he won election to the State Senate, and served there from 1863 until his sudden death from a heart attack in 1868. He was widely admired and considered likely to become the next Governor. ↩

- Journal of the 22nd Senate of the State of New Jersey, being the 90th Session of the Legislature, 1866 (hereafter Senate Journal), p. 54. Apparently the expression “on leave” meant that the Senator was recognized by the Chair (given leave to introduce a bill). It did not mean that the Senator was on vacation and making use of a proxy. ↩

- James P. Snell, History of Somerset and Hunterdon Counties, chapter on The Bench and the Bar, p. 215. ↩

- Egbert T. Bush, “Kingwood Tavern, Substantial Relic,” Hunterdon Co. Democrat, April 23, 1931. It is a little amusing to see the phrases that Bush put in quotes, as if they were not commonly used. ↩

- The Senate Journal is not very helpful when it comes to identifying party affiliation. Neither are typical biographies. I resorted to stories in the Trenton newspapers to get information on these senators. ↩

- During the years following the Civil War, Johnson was a very controversial figure. He tried to follow Lincoln’s plan to reconcile the southern states with the rest of the country, although for very different motives than Lincoln had. Johnson was a southerner and a decided racist. Lincoln was thinking more in terms of healing the Union. However, Johnson’s plan was overwhelmingly opposed by Republican Congressmen who wanted revenge and punishment for the South. It didn’t help that Johnson was a little uncouth and short-tempered. This is explained very succinctly in Paul Johnson’s A History of the American People, a very well-written book. ↩

- Senate Journal, 1866, p. 214. ↩

- Senate Journal, p. 393. I cannot explain why Sen. Scovel of Camden, a Republican, was acting as president of the Senate. ↩

- Senate Journal, 120th Session of the Legislature (1896), p. 262. ↩

- Thanks to Shane Blische for information about this railroad. ↩

- H.C. Deed Book 137 p. 12. ↩

- Henrietta Kuhl had married Lambert N. Boeman in 1856 and had two children with him. But Boeman was killed in 1864 in the Civil War. Like many widows, Henrietta went to live with her mother, and later on with one of her children. ↩

- Republican supporters the Democratic nominees for president and vice-president in 1892. Grover Cleveland’s running-mate was Adlai Stevenson, I (1835-1914), whose grandson Adlai E. Stevenson ran for president in 1952 and 1956. By the way, Cleveland won all ten of NJ’s electoral votes. ↩

- Assembly Minutes, 1896, p. 222. Heather Hustead, Electronic Resources Librarian was very helpful to me when I began this research, as the Assembly Minutes of 1896 are not digitized on the State Library website, so one must “consult the print volume,” which she did. After pursuing this some more I found that Hathi Trust does have the minutes online (see Hathi Trust). Catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/008888225. Subsequent dealings with Senate Bill No. 111 in the Assembly can be found on pp. 224-25, 249, 279, 280 and 303-04. ↩

- Assembly Minutes, 1896, p. 303. It is not yet known if that remonstrance hiding somewhere in the State Archives. ↩

- Assembly Minutes, 1896, p. 304. ↩

- Senate Journal, 1896, p. 439. ↩

- Trenton Evening Times, March 17, 1896, p. 1. I asked my favorite political expert if he knew what a “caucus measure” meant. He said this was not a current practice and thought that it was probably a requirement that all Republicans vote for the measure and not absent themselves. ↩

- Gov. Griggs did not fill out his term of office; he resigned in 1898 to become U.S. Attorney General in the administration of William McKinley. ↩

- For a nice short history of Hunterdon’s railroads, see the chapter on “Transportation” in The First 300 Years of Hunterdon County, 1714 – 2014, published by the Hunterdon County Cultural & Heritage Commission. ↩

- A map of the area being moved to East Amwell will be shown in part two. ↩

- For an amazing (fictional) portrayal of Wm. J. Bryan, see the movie “Inherit the Wind,” with Bryan portrayed by Frederick March. In the movie, he was named Matthew Harrison Brady. ↩

- I got some of this information from the Legislative Manuals, which are online. They are a goldmine of information. Note: In 1897, State Senators had 3-yr terms, but Assemblymen only 1 year. Salary for both was $500 for the duration of the elected official’s term. See NJ State Library. Also see Wikipedia (“Political Party Strength in New Jersey) which doesn’t always agree with the Legislative Manual’s numbers. Legislative sessions generally extended from January through March, although occasionally special sessions were added in April. ↩

- Trenton Evening Times, Feb. 23, 1894, p. 1. As you might have guessed, this paper leaned Republican. ↩

- Portrait and Biographical Record of Hunterdon County, published about 1897, p. 209-10. ↩

- A lengthy description of the disaster can be found in the Hunterdon Republican, Nov. 11 and Nov. 18, 1896. ↩

- H.C. Deed Book 247 p.36. The deed said nothing about a handle factory. ↩