Halloween is almost here. The days are getting much shorter, the nights much longer, and soon we will wind our clocks back to make the night seem even longer.

There are two ways to think about this time of year. The cheerful way is to glory in the fall colors and delight in children running from house to house on Halloween, many of the boys dressed as pirates (though not as much as in years past).

The darker way (which can exist in our minds simultaneously), is to be haunted by the unknown on dark windy nights. One of the most frightening things to encounter on a dark 17th century night was the sight (and smell) of a gibbeted body swinging from a post.

Put Halloween, pirates and gibbeting together, add some interesting early New Jersey history, and what do we get? Captain Kidd!

Becoming a Pirate

William Kidd was born in Dundee, Scotland about 1654. His father, Capt. John Kyd, died at sea, so his son William grew up learning to be resourceful on his own. We know nothing else of his youth, until he showed up in New York City in the 1680s. What prompted Kidd to leave Scotland for New York may have been “The Killing Time,” when Presbyterian separatists who refused to submit to the Church of England were hunted down and executed, making it a good time to leave Scotland and move to America.

Being a young man with little to lose, William Kidd joined a French and English pirate crew that sailed the Caribbean. Following a mutiny on the ship, Kidd was named the captain and the ship was renamed Blessed William. Soon afterwards, the English-held island of Nevis hired the ship and its crew to help it defend itself against the French. This included capturing ships and sharing the booty. Kidd and his crew were quite successful and returned to New York much richer than when they left. New York was something of a haven for pirates while Benjamin Fletcher was governor, so Kidd made himself comfortable, built himself a mansion and in 1691 married a rich widow, Sarah Bradley Cox Oort.

The Fateful Trip

Gov. Fletcher was replaced as governor of New York, Massachusetts and New Hampshire in late 1695 by Richard Coote, 1st Earl of Bellomont. At the time, Kidd was enjoying the life of a gentleman, retired from piracy. Gov. Bellomont put William Kidd in a tight spot by asking him to go on an expedition to attack pirates and enemy French ships that were harassing the coast, in effect, to return to piracy. Bellomont was asking Kidd to break the law for the benefit of England and the colonies. It was dangerous work, but it must have appealed to Kidd’s sense of adventure.

A ship, a new crew, and necessary supplies could only be found in England, as well as the necessary financial backing, which Kidd got from some of England’s most powerful men. He was even given a ‘letter of marque’ by William III, in which the king reserved for himself 10% of whatever plunder Kidd could seize. Kidd also raised money from his friend Col. Robert Livingston. But it wasn’t enough, so Kidd had to make up the difference.

Kidd fitted out a ship called the ‘Adventure Galley’ with a crew of 150 men and set off down the Thames. But he got off to a bad start when he neglected to salute a naval vessel that was sailing upriver at the same time. The naval captain’s retribution was to impress most of Kidd’s crew. He had barely enough men left to sail to New York where he signed up a new crew, but he had to settle for what was available which meant mostly riffraff and criminals, and he had to promise to pay them wages that were higher than he could afford. When the piracy proved disappointing, the crew went unpaid, which soon led to mutiny.

I will skip over how Kidd killed one of his crew and how it all came to an end in Madagascar (where some of his treasure was recently found). Most of the crew abandoned him, so he decided to return home. But by this time, his supporters back in England had also abandoned him, leaving him to enjoy the role of scapegoat. An order went out ordering his arrest as a pirate. He managed to get to New York secretly, and is supposed to have found a place to bury treasure with which he hoped to bribe Gov. Bellomont into giving him a pardon, as depicted in this picture:

Gov. Bellomont, who had been instrumental in sending Kidd to the high seas, now wanted to avoid any blame for Kidd’s misadventures, so he lured Kidd into a trap and arrested him in Boston in July 1699. Kidd was held in prison for a year before being sent to England to be tried before Parliament.

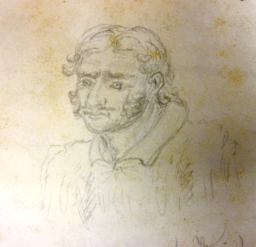

A Portrait of William Kidd

It was probably about this time, that someone taking notes for the Proprietors of West New Jersey in Burlington must have gotten bored and found some empty space on a page of the minute book dated 1682. Instead of senseless doodles, he drew a sketch of William Kidd.1

There was another sketch drawn on the same page of the minute book. It was of Samuel Jennings, one of the most passionate advocates for the independence of the West Jersey Proprietors from governance by Daniel Coxe. Coxe claimed to be governor of the province based on his vast holdings of proprietary shares. He sold out to the West Jersey Society, who also claimed the right to govern. But resident proprietors, mostly Quakers led by Samuel Jennings, strongly disagreed.

This portrait of Jennings is less than sympathetic. If nothing else, it makes him look like an old man, when he was really only about 50 years old. More important, it makes him look like a fanatic. This face would certainly make a good Halloween mask. The artist must have been an opponent of Samuel Jennings.

This led me to ponder who the artist might have been. In the original version of this article, I settled on the name of John Tatham, who may very well have visited William Kidd while he was languishing in a jail cell in New York City, from July to December 1699, and who also was one of Jennings’ greatest opponents. One of the reasons for this notion was that I had thought the pictures were drawn in the Minute Book of the Council of West Jersey Proprietors. In 1699, Tatham had access to that book. But I was completely mistaken about the source, leaving me with no easy answer to who the artist might have been.

I will explain how this error came about in the next post.

Kidd’s Execution

After a year in prison, Kidd was sent to London to be tried by Parliament. During this time, Kidd managed to have his portrait painted, and it is not hard to find a resemblance between this gentleman and the more desperate version in the West Jersey Proprietors’ minute book.

After a year in prison, Kidd was sent to London to be tried by Parliament. During this time, Kidd managed to have his portrait painted, and it is not hard to find a resemblance between this gentleman and the more desperate version in the West Jersey Proprietors’ minute book.

Kidd got little sympathy from Parliament. His Whig supporters had been ousted by a new Tory government, which found Kidd’s trial to be the perfect opportunity for discrediting the Whigs. It was expected that Kidd would name the supporters who raised money for his expedition, but he refused. Because of this, no leniency was given, and he was condemned to death. And not only that. Because the government felt it necessary to make an example of William Kidd, his judges went one step further—not only would he be hanged, he would also be gibbeted.

The word is not used very often these days. I had a notion it had something to do with hanging, but only now have I learned how gruesome a procedure it was. If you are of a squeamish nature, you might skip this part of the article. But if you like ghoulish things for Halloween, this is right up your alley.

Kidd’s execution by hanging took place at Execution Dock at Wapping in London. When a person is gibbeted, the body is enclosed in a form-fitting cage and hung until it has completely skeletonized, which can take years. I am unclear as to whether Kidd was hung in the normal way and then gibbeted, or if he was caged alive before being hung. In either case, the process of decomposition was far more uncomfortable for people passing by than it was for the victim. And not just because of the smell. The caged body would sway in the wind which made the chains it was hanging from to creak. Imagine passing by on a windy night. It is hard to say what you would notice first—the terrible smell or the sound of creaking chains. But one thing is certain—nearby residents and passersby certainly remembered the story of Captain Kidd and his terrible end.2

Afterthoughts

There is one thing that Kidd, Jennings and Tatham all had in common—they left Great Britain because of religious persecution, of Presbyterians, Quakers and Catholics. That made them all outsiders, in a sense, and influenced the choices they made in life.

Looking at the two portraits of William Kidd, it is hard to think of him as a complete villain, despite his rough life—perhaps more sinned against than sinning.

If it was indeed John Tatham who drew the portrait, then at least he did one good thing in his life. Of course, his treatment of Samuel Jennings was not so good, and unfortunately for Jennings, I do not know of another likeness of him.

It strikes me that this sketch of William Kidd is something very special. As far as I am aware, it has not been made public before now. It is one of the many treasures under the care of the New Jersey State Archives. If you are not yet a fan of the Archives, these two pictures might convince you to become one.

Happy Halloween!

Footnotes:

Much has been written about Kidd by scholars who have spent far more time on the subject than I ever will. If you wish to learn more about him, it’s probably best to start with Wikipedia and take advantage of the footnotes there. You might also check out an article by Michael J. Launay for Weird NJ, published in the Asbury Park Press on August 24, 2014. Also Pirate Lauriate by William Hallard Bonner, Rutgers University Press, 1947, p. 86.

- The minute book is on file at the N. J. State Archives. I came across this drawing back in 2010. It’s taken seven years for the perfect time for me to write about it to come along. ↩

- For a lengthier description of gibbeting, see Atlas Obscura, “The Incredibly Disturbing Medieval Practice of Gibbeting” by Andy Wright, 11 Oct 2016. ↩

Goodspeed Histories: The Plot Thickens

November 6, 2017 @ 10:23 pm

[…] So, first I had to amend the original article: A Story for Halloween […]