This article is a continuation of the article by Egbert T. Bush titled “When Stockton Was Not So Dry.” (Part One and Part Two.) Today I will enlarge on Mr. Bush’s short history of the Stockton Inn, which is now for sale. It is my hope that by fleshing out this history, a purchaser might be found who will value it as well as the lovely architecture of the place.

Bartles & Vansyckel

When I left off, Charles Bartles and Aaron Vansyckel, the big real estate investors of Hunterdon County in the mid-19th century, had purchased the Johnson tavern lot from Mahlon Fisher in 1849 for $4500.1 The property was described as being “A certain farm, tract or parcel of land and Tavern” of 53.87 acres, which extended along Main Street from the old Howell’s Tavern lot to a point near the school, north along Route 523 and south to the river. It excluded land already conveyed to The Centre Bridge Company and the D&R Canal Company, plus a small lot cut out for Mahlon Fisher’s sawmill.

Note, 5/5/2021: While doing research for the article “A Stockton Hotel Register,” I discovered some missing owners of the hotel during the 1850s. I am adding them here now, and deleting a couple paragraphs that were based on a lack of information.

Bartles and Vansyckel were shrewd real estate investors. They saw the benefits of the Inn’s location where Asher Johnson built it, opposite the entrance to the new bridge across the Delaware River. On July 9, 1850, Bartles & Vansyckle sold to the Centre Bridge Company the property for a public road that would run from the feeder canal at the Bridge in “a straight line to the centre of the present Hall door of the tavern house now owned by the sd Bartles & Vansyckle.”2 Hence, today’s Bridge Street.

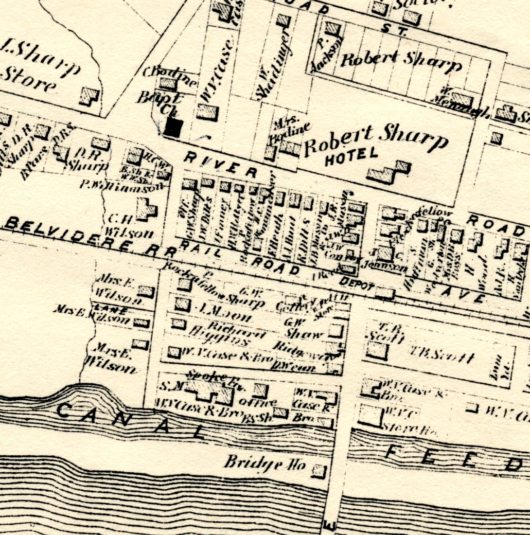

Like their other properties, Bartles & Vansyckle were not involved in day-to-day maintenance of the Stockton site. They turned their attention to other investments and left Jeremiah Smith to run the tavern. He was in charge in 1851 when the Cornell Map showed “Smith’s Hotel” where the Stockton Inn is now. (For a view of that map go to the previous post, part two of Mr. Bush’s article.) It is interesting to me that the deed of 1849 referred to “the tavern lot,” but by 1851 the Cornell Map called it a hotel. The 1850 census described Jeremiah Smith as an Innkeeper, so if Asher Johnson had not been letting out rooms at his tavern, then Jeremiah Smith certainly was. Mr. Bush had written that after purchasing the lot, Bartles & Vansyckle enlarged the hotel in 1850, but he gave no source for that information. It may have been Smith who was in charge of the expansion.

William W. Mettler

On April 1, 1857, Bartles & Vansyckle created a new lot out of the original 53.87 acres amounting to 3.97 acres, and sold it to William W. Mettler of Delaware Township for $4500.3 Later that month, on April 222nd, Mettler was granted a tavern license. I suspect that Mettler was already in charge of the tavern when he bought it. On October 26, 1856, he was appointed Postmaster of Stockton.

William W. Mettler was born in 1820. I am not sure who his parents were, but my guess is that his father was Reuben Mettler of Amwell (1780-1850) who was buried in the same cemetery, Amwell Ridge, as William was. I can say for certain that on May 23, 1840, William W. Mettler married Elizabeth Ann Bellis (1815-1849), daughter of David Bellis and Eleanor Schenck of Raritan Township. (The Bellis’s were also buried in the Amwell Ridge Cemetery.)

On April 4, 1859, Mettler was found dead in his cellar. The Hunterdon Republican reported that the cause of death was “a supposed apoplectic fit.” Because he had not written a will, administration of his estate was granted to Abraham Cray and Garret S. Bellis. On Nov. 16, 1859, they advertised the hotel property for sale; those interested were invited to visit the place, where Bellis was in residence and Joseph Titus was operating it. A year later, on Nov. 10, 1860, Cray & Bellis sold the 3.97 acres to Joseph H. Titus of Stockton for $4830, at a public sale.4

Joseph H. Titus

Titus, born Feb. 16, 1824, was probably the son of Theophilus Titus and Elizabeth LeGare. His wife’s name was Delilah Ann, but her maiden name is not known. The couple had 9 children, but most of them died as infants. They were counted in the Delaware Township census for 1860, with Titus as a hotel keeper owning property worth $6,000. The only hotel guest was on John Convoy 35, a Pennsylvania stone cutter.

Titus did not stick with it very long. On March 28, 1861, he sold the hotel and the lot of 3.97 acres to Thomas P. & Charles Holcombe for $6,000.5 The Holcombe brothers were sons of Richard Holcombe and Elizabeth Closson of Lambertville. Charles had moved to Solebury, but Thomas settled in Stockton as early as 1821, purchasing the old Anderson farm south of town. In 1841, he bought the John Prall farm of 250 acres.

On Nov. 4, 1861, Charles and Thomas Holcombe sold the tavern lot of 3.97 acres to Robert Sharp of Delaware Township.6 In the previous version of this article, I had written that Charles Bartles had conveyed his share of the lot of 53.87 acres in Stockton to Aaron Vansyckle, who then sold it to Robert Sharp. I was mistaken in thinking the tavern lot was located there. These were simply additional properties acquired by Sharp.

Robert Sharp

Robert Sharp was the eldest son of Col. John Sharp, one-time owner of the store lot described in Part One. He married Sarah Prall about 1843 and had four children with her. She died in 1851. About 1855, Sharp married his second wife Elizabeth Menaugh. They had one child (as far as I know) who died age four.

Egbert T. Bush had mentioned Robert Sharp in another of his articles titled “Brookville and Up the Hollow” (Dec. 26, 1929), in which he wrote that “Robert Sharp, 2nd, lived in the upper tenant house on the Colonel Sharp lowlands, and did the farming from 1844 to 1850.” This farm was at Sandy Ridge. In the 1850 and 1860 censuses, Robert Sharp was listed as a farmer. But in the 1870 census, Robert Sharp, age 47, was “keeping B. house.”

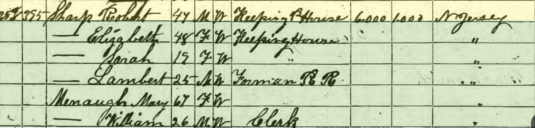

At first I thought that the initial was a P, which could stand for poor house, but that didn’t make sense, since the other occupants of the household were not identified as paupers. They were his wife Elizabeth 48 (1822) keeping house; daughter Sarah 19; son Lambert 25, forman [sic] on a railroad; his mother-in-law Mary Menaugh 67; and Elizabeth’s brother William Menaugh 26 clerk. Clearly this was neither a poor house nor a hotel. If you look closely at the census record you will see “B. House,” which must have meant boarding house. It was not much of a boarding house in 1870. But as far as Beers was concerned, it was a hotel.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, an Inn was a place where you could get a drink, a meal and a bed, while taverns usually supplied the drink (plenty of it), and perhaps a little food, depending on the owner’s predilection. Going by the licenses given to Robert Sharp, he was definitely running a tavern in Stockton, if not a hotel, from 1871 to 1874. By that time, Sharp seems to have tired of the business because in 1874 he built himself “a fine residence near the Hotel,” and retired from inn-keeping.7 He sold the hotel lot (1.82-acres) on August 11, 1874, to Sarah S. Hockenbury for $10,000.8

This did not exhaust Sharp’s property. He sold six other lots afterwards, including one to Sarah Hockenbury’s husband, John S. Hockenbury, between 1875 and 1880.

Sometime after the death of his wife Elizabeth, on August 13, 1878, Sharp lost his ability to cope. He was committed to the Lunatic Asylum at Trenton, where he died, at the age of 57, on November 7, 1881. Robert Sharp and both his wives, Sarah and Elizabeth, were buried at the Sandy Ridge Cemetery.

John S. and Sarah Hockenbury

John Sutton Hockenbury was one of eight children, born August 5, 1821 to John Hockenbury, Sr. and Sarah Sutton. The family lived in the Croton area in Kingwood Township. John S. Hockenbury and Sarah Rittenhouse were married on November 25, 1843.9 They had ten children, from 1844 to 1867. Two of them died young.

At the time that Sarah Rittenhouse Hockenbury bought the tavern lot she was 50 years old. She was a married woman buying real estate in her own name, and she paid plenty for it, which was very unusual. Her husband John already had a great deal of real estate of his own. He certainly could have purchased the inn himself. Was Hockenbury having some money problems that made him temporarily unable to purchase in his own name? Or was it that Sarah was keen on running a hotel herself? Unless we come across a letter or other document pertaining to this we can never really know.

Adding to the mystery is the fact that this was the only deed recorded with Sarah Hockenbury as the grantee. And even though the Inn was purchased in Sarah Hockenbury’s name, it is clear that her husband was in charge. It was John S. Hockenbury who acquired tavern licenses for the Inn at Stockton from 1874 to 1899, as indicated in the abstracts of the Hunterdon Republican by Bill Hartman. (He may have continued to obtain tavern licenses up until his death in 1914, but the Hartman abstracts end with 1900.)

John S. Hockenbury had been in the hotel business as early as 1857, when he was running a hotel in Flemington. He sold it sometime during the Civil War and temporarily retired from the business.10 In the 1870 census, he was identified as a commercial traveler, age 48, living in Raritan Township (probably in Flemington), with wife Sarah, age 45, and seven of their children at home. But in 1880, after Sarah’s purchase of the Stockton Inn, John S. Hockenbury was again a hotel keeper, age 58, living in Stockton. In both cases, Sarah Hockenbury was merely “keeping house.” Five children were at home in 1880, with son William T. Hockenbury 28 working as “hotel clerk.”

While Hockenbury ran the Stockton Inn, he was often elected as one of the pound keepers for Delaware Township. So there must have been a fenced area on the property where stray animals could be kept. Fairly prominent people came to visit the Hotel. They signed a register that Egbert T. Bush got a look at many years later. For more see “A Stockton Hotel Register.”

Hotel keeping was always somewhat risky. In 1876, someone broke into the cellar and stole some whiskey and “provisions.” In 1878, the Hockenbury’s daughter Mary, wife of Lemuel Fisher, got a surprise. As the Republican reported:

On Wednesday afternoon last [17 July 1878 ?], Mrs. Lemuel Fisher and some lady friends were visiting Mrs. Fisher’s father, John S. Hockenbury in Stockton, and went down to the river to bathe. While thus engaged, a shot rang out and Mrs. Fisher immediately exclaimed that she had been shot. Blood ran down from her neck and a physician was called. Fortunately, she was just slightly injured. The accident was caused by some boys who were shooting at a target and did not see the ladies.11

In 1879 when Hockenbury applied for his annual tavern license, there must have been some sort of problem because for the first and only time, the application was “held for Inquiry.” After a couple weeks the problem, probably financial, was resolved and the license granted. (A look at the tavern licenses might shed light on this incident.)

Tragedy hit the Hockenbury family in 1885. Their son William, age 32 and unmarried, “died suddenly in New Hope, PA.” The coroner’s jury determined that “his death resulted from excessive use of liquor.”12 The death certificate claimed it was a heart attack.

In 1887, an interesting experiment took place to find out for certain what the distance was from Stockton to Flemington. According to the Hunterdon Republican (June 1, 1887), it “has long been a matter of dispute” in Stockton.

Some contended that it was not over 9 miles, while others were sure that it was nearer 10 than 9 [miles]. Rev. Cornelius S. Conkling determined to have the matter settled and a party was organized, principally under his direction, to chain the road and ascertain the precise distance. On Tuesday morning last, the party started bright and early. David Lawshe and William Menaugh, carrying the chain and Capt. Lewis ? & Asa Rittenhouse drove a stake every mile. The distance as chained was 10 1/8 miles from the Hotel of John S. Hockenbury in Stockton to the Court House in Flemington. The distance has always been said to be 9 miles and the distance from Stockton to Sergeantsville, which has always been called 3 miles, was found to be 3 1/2 miles.”13

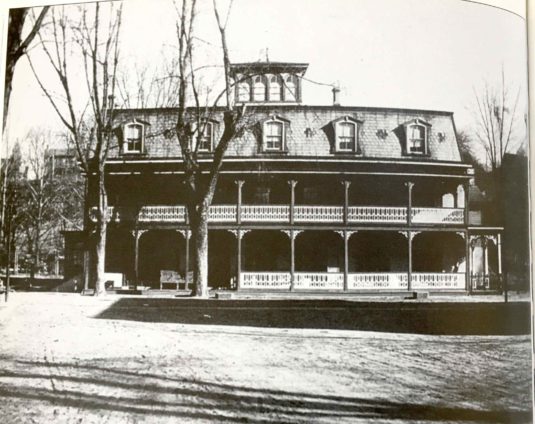

The above photograph is taken from Prallsville Mills and Stockton by Keith Strunk (the Arcadia series). It pictures the Stockton Inn the way it was in the 1890s, after John S. Hockenbury had enlarged it to three stories, with a mansard roof and cupola.14

The above photograph is taken from Prallsville Mills and Stockton by Keith Strunk (the Arcadia series). It pictures the Stockton Inn the way it was in the 1890s, after John S. Hockenbury had enlarged it to three stories, with a mansard roof and cupola.14

I mentioned before that hotel keeping was risky. It appears that in 1893, Hockenbury, who should have known better, got the wool pulled over his eyes. Once again quoting from the Hunterdon Republican (Dec. 13, 1893):

A Slick Rascal. A smooth tongued individual recently made his appearance at the hotel in Stockton and John S. Hockbenury, the landlord, was easily duped. The stranger told him that he was the advance agent for a party of men employed by the Western Union Telegraph Co. and that 9 men would arrive on a special train the next day. After eating a hearty meal, having a good night sleep and a breakfast, he discussed the planned arrival in more detail. Saying that he was going to take a walk, he disappeared without paying his bill.

Sarah Hockenbury died on January 27, 1898, age 74, and was buried in the Prospect Hill Cemetery. At the time of her death, the Stockton Inn was still in her name, but since real property in New Jersey was jointly owned by spouses, it remained in the hands of her husband. Hockenbury was 77 when Sarah died. Obviously he could not run the Inn himself, but he had sons to carry on for him. In fact, in the 1900 census, Hockenbury, age 78, was a landlord, and his son-in-law Jesse W. Weller was the hotel keeper. Weller married Annie Hockenbury about 1878, but they had no children. Also in the household in 1900 was Annie’s brother John H. Hockenbury, working as a bartender, sister Laura who never married, and brother Benjamin R. Hockenbury who worked as the bookkeeper.

I do find it irksome that the women’s work, which must have been considerable in a hotel, was never mentioned in the census records. And one cannot argue that it was because they were not paid. One often sees the term “keeping house” in those records, and that was certainly never compensated. I have little doubt that Annie H. Weller and her sister Laura were doing a considerable amount of work at the hotel. But they were assisted by Emma Mason, age 31, who was credited in the 1900 census with “general housework.” Also employed at the hotel was Charles O. Lewis 21, a hostler.

John S. Hockenbury wrote his will on May 27, 1902. He left $100 in trust for the “repair and beautifying my burial plot in said cemetery.” In light of the fact that many of his children were also buried there, it was a wise investment. He also left $500 to his granddaughter Sarah, daughter of his youngest child Benjamin R. Hockenbury. (The will did not name Sarah’s mother.) Finally, he ordered his executors to sell all the rest of his property and divide the proceeds between his six surviving children: Mary Elizabeth Fisher, Amy Kinney, John H. Hockenbury, Annie Weller, Laura V. Hockenbury and Benjamin R. Hockenbury. His executors were son John H. Hockenbury and friend Richard S. Kuhl.

John S. Hockenbury wrote a codicil to his will on September 9, 1905 because his son John H. Hockenbury had “become incapacitated for doing business.” In his place he named his son-in-law Lemuel Fisher, husband of his eldest child, Mary Elizabeth. But on January 19, 1909, Hockenbury had to write another codicil because Lemuel Fisher had died in 1906. Why he waited until 1909 is a mystery. The new executor was another son-in-law, Jesse W. Weller, who had been operating the hotel since 1900.

By 1910, John S. Hockenbury was 88 and still living at the hotel, but by this time he was boarding there (according to the census), living on his own income, and the hotel was run by Spencer L. Dilts, who was not related. Dilts had begun renting the hotel in 1904 and, according to E. T. Bush, continued to do so until after Hockenbury’s death, which occurred on January 28, 1914, when he was an impressive 92 years old. He was buried next to wife Sarah, and sons Oakley C. and William Hockenbury in the Prospect Hill Cemetery. After his death, his executors followed his directions and sold his property, including a few lots in Stockton. Of course there is only one we are interested here, and that is the hotel lot.

The Colligan Inn

On April 1, 1915, the executors of John S. Hockenbury dec’d (Richard S. Kuhl and Jesse W. Weller) sold the hotel lot of 1.82 acres to Enos Weiss for $12,500.15 On the same day, the executors sold to Weiss’ daughter Elizabeth Colligan for $130 two small lots in Stockton bordering the hotel lot.16

Enos Weiss was an interesting character. He immigrated from Alsace Lorraine in 1872 when he was 19 years old, and settled in Doylestown, PA where he probably met his wife Mary Luly, daughter of German immigrants. Weiss worked for several years in Doylestown as a baker. His wife Mary gave birth to four daughters, but died in 1887. A couple years later, Weiss married Susanna L. (maiden name not known) and had four more children.

In 1900, the Weiss family was living in Lambertville where Weiss worked as a hotel keeper, probably at the Lambertville Inn on Bridge Street. He was 47, renting his home, and his wife Susanna was 36. They had nine children, seven of whom were still alive: Elizabeth 19 (Aug 1880), Emma 18 (Mar 1882), Mary 15 (Mar 1885), A. Neddie 13 (Dec 1886), Agnes 11 (Apr 1889), Leonard 9 (Apr 1891), Eleanor 7 (Apr 1893).

Also at the hotel was William Colligan 25 (Apr 1875 PA) single, bartender, born at Centre Bridge in Pennsylvania; servant Charles Tunison 30 (Jan 1870) single, porter; servant Mary Curtis 19 (May 1881 NJ) and cook Hattie Daniels 32 (Nov 1867 DC) both single. Their boarders were Frank S. Andrews 29 (Mar 1871) pool room keeper, wife Nellie 24 (Mar 1876), married 5 years, no children; Wm. Hart 43 (Aug 1856) carpenter, wife Hattie 40 (Feb 1860 ) married 22 years, 2 children, 1 still alive; and John Hughes 37 (Nov 1862 Ireland) single, foreman at the quarries.

Not long after this, Weiss’s daughter Elizabeth married the bartender, William P. Colligan. According to his draft registration card of 1918, William Colligan was tall and slender with grey eyes and light brown hair. The Colligans had five children, from 1901 to 1913, which means some were born in Lambertville, and the rest in Flemington.

The first time Enos Weiss appeared in the list of Hunterdon County deeds was on March 18, 1907, when he was resident in Lambertville and purchased from William H. & Mary A. Cawley of Somerville for $36,000 the County Hotel on Main Street in Flemington. It was sold in two lots, the first bordering Isaac G. Farlee dec’d, a lot of Richard K. Reading now G. A. Allen, and the street running through Flemington (Main St); and the second bordered by the Reading lot, the Farlee lot, and New Street. The hotel property had formerly been owned by Wm. Ruohl.17

Weiss financed this huge purchase in a couple ways. First he got a mortgage from the Cawleys for $6,000.18. And on the same day, the day of the sale, P. Ballantine & Sons of Newark, NJ loaned him $5,000 for “a period of ten years” in exchange for the promise not to sell “any malt liquors other than those made and supplied by said P. Ballantine & Sons.”19 Sounds rather like “in restraint of trade.” One wonders what Weiss’s customers thought of this arrangement.

The 1910 census shows Weiss, age 56, living in Flemington and running the County Hotel, but it stated that Weiss was renting, which doesn’t make sense. His wife Susan was 42 years old. Three of their children were living with them: Agnes 21, Leonard 19 and Eleanor 17, and there were only three boarders. Meanwhile, William and Elizabeth Colligan were living in their own house in Flemington on Main Street. William was working as a clerk in the hotel, and Elizabeth was caring for four sons, William 8, Leonard 7, Edward 5 and Charles 2.

When Enos Weiss bought the hotel in Stockton in 1915, he was 62 years old. It is a question why Weiss decided to switch from the County Hotel in Flemington to Hockenbury’s Stockton Inn. Perhaps he had always wanted it but it did not become available until after Hockenbury’s death. Or perhaps running the hotel in Flemington no longer appealed to him. In any case, he was able to manage it with the help of his daughter Elizabeth and her husband William Colligan.

By the time of the census of 1920, Enos Weiss had retired from hotel keeping. He was 66, while wife Susanna was 52, and son Leonard living with them was 28, working as an automobile salesman. They lived in Stockton, but in a separate house from the hotel which was now directly under the control of William Colligan, but Enos Weiss was still the owner. William was 44, wife Elizabeth was 39. Their sons living with them were William I. 18, laborer, Leonard J. 16, Edward A. 14, Charles J. 12, and John W. 7. Note that Elizabeth named her son Leonard after her brother Leonard. There was only a twelve-year difference between them.

Boarding at the Stockton/Colligan Hotel were Charles Burns 57 single, janitor at a school building (probably the Stockton school); Johnson Warford 62, NJ lineman for Standard Oil Co.; and John H. Race 64 widowed, caretaker at a livery stable.

Only five years after acquiring the Stockton Inn, Enos Weiss and the Colligans suffered a setback, as did all the other tavern owners in the country: The Prohibition Era had begun. According to the Inn’s history on its website, the Weiss family managed to get around the problem by turning their tavern into a speakeasy, where “Whickecheoke Cyder” was a popular drink. The Inn became such a popular place that Weiss and the Colligans were motivated to add not just additional rooms, but a lovely feature behind the old well—a small waterfall tumbling down the rocky ledge behind the building.

Financial Troubles

Recall that when Enos Weiss bought the County Hotel in Flemington, he paid $36,000 for it. He had to finance it with mortgages as well as his savings. Things were getting difficult by 1918 when he and Susanna had to get a $3,000 mortgage from their son Leonard,20 and in 1921 to sell a lot to John S. Hendricks, a familiar name in Stockton.21 But this was not enough to save Weiss from his debts.

On September 14, 1921, the Supreme Court of NJ ordered the sheriff of Hunterdon County, Arthur W. England, to levy on the goods, chattels & real estate of Enos Weiss in order to satisfy a debt of $3,000 owed to none other than P. Ballantine & Sons. The sale was made on January 6, 1922, when the highest bidder, at $1200, was Enos Weiss’s daughter Elizabeth Colligan.22 Once again the property became owned by a married woman.

I should make note here that the history that is found on the Stockton Inn’s website claims that the Inn was purchased at auction by Elizabeth Weiss from her mother, Agnes Weiss. Elizabeth’s aunt was Agnes Weiss, but she had nothing to do with the sale. That history also claimed that Elizabeth had married Joseph Colligan, an artist who worked part time at the inn as a bartender. This is certainly not true. Elizabeth married William Colligan, whose father was named Joseph. William did work as a bartender at the County Hotel in 1900, but in 1910 he was working as a clerk in the hotel, and by 1920 he was the hotel manager.23

One of the Colligans’ most notable boarders was Egbert T. Bush. In the census of 1930, he was 81 years old, widowed, and living at the Inn. The previous year he had written his article, “When Stockton Was Not So Dry.” I have little doubt that Mr. Bush allowed himself a glass or two of “Wickecheoke Cyder.” He died in 1937, age 89.

William P. Colligan died on July 18, 1931, age 56. The online history stated that after Colligan’s death their five sons ran the inn with their mother. This is not entirely true. In 1930, William Jr. was a contractor driving a stone truck and in 1940 he was a plumber. In 1930, son Edward was a bookkeeper at a stone quarry in Hunterdon, but by 1940 he had joined the family enterprise and was working as manager of a private hotel in Stockton, at which time the younger sons, Leonard, Charles and John were all employed as clerks in a “private hotel.”

Old-Fashioned Hotel Keeping

One of the consistent themes in this story is how much hotel owners depended on their families to provide the necessary labor to maintain the hotel. The wives were relied on for not only housekeeping and laundry, but also the meal planning and cooking. Sons acted as clerks and bartenders. The pater familias probably spent much of his time welcoming guests, ordering supplies & provisions, and making sure that everything was running smoothly. It was a demanding business for these individual owners. The scale of these operations was not far different from today’s larger bed & breakfasts, with the difference that these families had no efficient appliances with which to clean and cook, and heat was provided by fireplaces or coal stoves. It was hard work, but in those days hard work was the norm.

Hotels in the larger towns, like the County Hotel and the Union Hotel in Flemington, and the hotel in Lambertville, required much more staff. That may also have been a factor in Weiss’ failure with the County Hotel. In Stockton, Weiss’s family was large enough.

Enos Weiss lived to the ripe old age of 83, dying on June 5, 1936 at his home in Stockton. Wife Susanna survived him until her death on May 30, 1947, age 79. They were buried at St. Mary’s Cemetery in Doylestown.

Through the 1940s and 50s, Colligan’s Inn carried on, becoming a haven for many well-known writers, artists, songwriters and journalists. But that is another chapter is the history of this ‘small hotel with the wishing well.’ (Thank you, Richard Rogers.) I will leave it to someone else to write that history—it is certainly worth doing.24

Footnotes:

- H. C. Deed Book 94, p. 33. ↩

- H.C. Deed Book 98 p. 101. ↩

- H.C. Deed Book 116 p. 346. ↩

- H.C. Deed Book 124-036. ↩

- H.C. Deed 125-682. ↩

- H. C. Deed Book 125 p. 680. ↩

- Hunterdon Republican, June 4, 1874. ↩

- H.C. Deed Book 158 p. 257. ↩

- I have not yet succeeded in linking Sarah up with her Rittenhouse family. Perhaps a Rittenhouse genealogist can help me out. ↩

- I confess I have not looked up his deeds for that period. ↩

- Hunterdon Republican, 25 July 1878. ↩

- Hunterdon Republican, Nov. 12, 1884. ↩

- For those unfamiliar with surveying terms, to “chain the road” meant to measure the distance with a surveyor’s chain, which was 66 feet long, and was the standard measure of distance for centuries. For more on this subject, see “Secrets to a Great House History.” ↩

- I regret to say that Mr. Strunk perpetuated the mistake that Elizabeth Wiess married Joseph Colligan. ↩

- H. C. Deed Book 313 p. 560. ↩

- H. C. Deed Book 314 p. 99. ↩

- H. C. Deed Book 282 p. 8. ↩

- H. C. Mortgage Book 91 p. 688. ↩

- H. C. Deed Book 282 p. 11. ↩

- H. C. Mortgages, Book 117 p. 447. ↩

- H. C. Deed Book 342 p. 522. ↩

- H. C. Deed Book 344 p. 644. ↩

- The earlier version of The Stockton Inn is very error-prone, and it has been repeated over and over in various publications. Expectations that my corrections will get widely known are very low. That’s just how it goes. ↩

- I have copies of many of the articles written by Iris Naylor for the Lambertville Beacon, several of them concerning the village/borough of Stockton. Sadly, none of them concern the Inn/Hotel, even though it seems likely she wrote about it a one time or another. Another major research job I have not undertaken. ↩