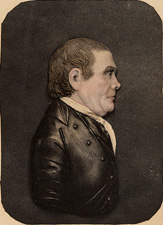

Two Letters Written by Sen. John Lambert

Senator John Lambert of Amwell is one of Hunterdon’s most interesting historical figures.1 He served in the state legislature during the Revolution and afterwards served as Acting Governor before being elected to Congress and then to the U.S. Senate.

But it wasn’t merely his high office and his influence on Hunterdon’s only city (i.e., Lambertville) that makes him interesting—it is his principled stand on whether to declare war in 1812.

John Lambert was born February 4, 1746 to Gershom and Merriam Lambert of Amwell Township and given the education appropriate for a member of the gentry. His father, Gershom Lambert, wrote his will in 1763, a few days before his death, ordering his farm in Amwell Township to be sold, but it appears from tax records that his son John gained possession of the 300-acre tract.

He married his first wife, Susannah Barber (1744-1779) about 1765. She was the daughter of John Barber and Magdalene Johnson, a well-to-do couple living near Mount Airy in Amwell Township. John and Susannah Lambert had seven children, three of whom died infancy. (See the Lambert Family Tree and the Barber Family Tree.)

Their first and only son Gershom died on July 12, 1779, only six years old. His mother died just a week later, at the age of 35. In a letter to his brother,2 John Lambert wrote: “I have not only lost a son, but my dear and loving wife.” Two years later, Lambert married his second wife, Hannah Little (1746-1835), daughter of John Little, Jr. and Mercy Longstreet of Shrewsbury, Monmouth County. John and Hannah were married in 1781 at Coryell’s Ferry, now Lambertville, and had three more daughters.

Lambert’s Political Career, 1780-1808

During the Revolution, John Lambert served as tax assessor for Amwell Township and as a Justice of the Peace. In March 1780, Lambert was elected to New Jersey’s General Assembly, which was created by the new state constitution in 1776. The Revolution was still in progress, with the Continental Army camped at Morristown, having endured the coldest winter on record. At the time, New Jersey was operating under the Articles of Confederation, which it had ratified two years earlier and which remained in effect until the Constitution became the law of the land in 1787.

The Revolution in New Jersey was a brutal affair, pitting neighbor against neighbor. Lambert, like other members of the Legislature, must have endured some hostility from his Loyalist neighbors, but he carried on.3

Following Independence and the conclusion of the Revolution, the NJ lawmakers were confronted with new challenges. They had to decide how their new state was to be governed in a brand-new country. Not only was democracy still in its infancy, but so was organized party politics.

There were still political divisions, but now, instead of loyalty to the King v. declaring independence, the disagreements concerned establishing a centralized federal government v. defending a collection of independent states. It is a little misleading to call the Federalists and Republicans of this period members of political parties. These groups were nothing like the political parties of today. There was next to no organization, and next to no democratic input from regular voters. And of course, those voters were limited to white male property owners. The parties, such as they were, were led by the elite, what is generally called the gentry—men who owned a significant amount of property and had influence with their neighbors, who were content to leave decision-making up to them.

John Lambert qualified as one of these elite, and as such was elected to the Legislative Council (equivalent of our State Senate) in 1791. In November of that year, the Legislature designated Trenton as the State Capital.

Lambert clearly had influence among his legislative cohorts, for in 1795 he was chosen to serve as vice-president of the Council. He was serving in this capacity during the presidential campaign of 1800, in which John Adams, the incumbent president and member of the Federalist party, was opposed by his own vice president, Thomas Jefferson, leader of the party calling itself Federalist Republicans or Democratic Republicans.

One would expect John Lambert to be a strong Federalist, given his position in society, but he was quite the opposite—a strong and early supporter of Thomas Jefferson and his view of the federal government. Of course, Lambert was not alone. After Thomas Jefferson became president in 1801, his party held onto the presidency for over twenty years, with Presidents Jefferson, Madison and Monroe. It was sometimes called the Virginia Dynasty.

In 1801 New Jersey had another legislative election. Remember, popular democracy did not exist yet—New Jersey, like the country as a whole, was a representative democracy, which means the popular vote only worked for electing state representatives. This was right after Thomas Jefferson had won the presidential election, so it is not surprising that in 1801 the Jeffersonian Republicans took control of the New Jersey Legislature from the Federalists, who had governed ever since George Washington became president in 1789.

The first act of the new state legislature of 1802 was to have a Joint Meeting (Assembly and Senate meeting together) to elect a new governor. It was this gubernatorial election of 1802 that is particularly interesting.

Even though they had the majority, the Republican officeholders were themselves divided by conflicts between East and West New Jersey. And the Federalists were still strong, though now in a minority. These conflicts became visible when the Legislature caucused to elect the Governor for that year. (At the time, NJ Governors were only elected for one-year terms.)

The current Governor running for re-election was Joseph Bloomfield of Burlington, a Republican from “West Jersey.” The Federalist candidate was Richard Stockton of Princeton. But the vote in Joint Meeting was tied, 26 to 26. As a result, John Lambert, as president of the Council, was given the position of Acting Governor, which he held until the next election in October 1803, when Joseph Bloomfield won back the Governorship.4

Election to Congress

The campaign of 1804 was another good one for Jefferson’s party. Not only did he win re-election to the presidency, but the eight at-large Congressional seats that New Jersey was entitled to all went to Republicans, who, as electors, all voted for Thomas Jefferson.

John Lambert won one of these seats, succeeding James Mott of Middletown, Monmouth County. And Lambert was easily re-elected to Congress in 1806. But once again, this was just a step in his rise to higher levels of political power.5

Election to the Senate

In 1808, James Madison became the successor to President Thomas Jefferson. (He was sworn in in 1809.) At the same time, a new state legislature was elected in New Jersey.6 At their Joint Meeting in November 1808, John Lambert was elected to the U. S. Senate, replacing John Condit of Orange, NJ. Condit had been appointed to that seat in 1802 due to the same deadlock that had made Lambert Acting Governor.

The Trenton Federalist was not happy with this choice. The editor’s complaint gives us a little insight into the ongoing East-West Jersey conflict:

Another Joint Meeting. On Thursday afternoon both Houses of the Legislature were convened in Joint-Meeting for the purpose of choosing a Senator of the United States, where JOHN LAMBERT was appointed ! ! !

Of all the appointments the democrat[s?] ever made in New-Jersey, this certainly is the most miserable. Poor Doct. Condit, the perfect Senator, was withdrawn from the nomination before the vote was taken. This fore mortification to the Essex and Morris members they well deserve for their intolerance in displacing Charles Ruffell.7

As it turned out, John Condit recovered nicely. Not long afterward, he was chosen to finish the term of Aaron Kitchell, and then elected to that seat in 1809, for a term that ended in 1817.

John Lambert took office in the U.S. Senate on March 4, 1809, his term to run until 1815. He could not have known that he would be faced with one of the Senate’s most difficult acts:

Declaring War

Great Britain had been at war with France and its aggressive leader, Napoleon Bonaparte, since 1803. One of Britain’s many concerns was to interrupt the trade between the new United States and its former ally France. Britain aggressively moved to eliminate as much of that trade as possible, often taking the liberty of boarding American ships and seizing sailors as well as cargo.

This was the bane of Madison’s first term as president and he struggled to deal with the problem. Finally, on June 1, 1812, Madison sent to Congress a list of grievances against Great Brittain. He did not overtly ask for a declaration of war, but it was understood.

However, there were good reasons for voting against going to war. As Ted Widmer wrote in his article “The War of 1812? Don’t Remind Me”:

Though serious at times, these irritants did not add up to grounds for war. England was America’s principal commercial partner and wielded the greatest navy on earth. To anyone who participated in the maritime economy—as most of New England did—it was the height of folly to risk everything over a few insults. Yet rhetoric, so easy to dish out, can be hard to take back.8

And party loyalty seemed to trump (excuse the expression) these more rational considerations. The president was a Republican, and the Senate majority was Republican. To vote against going to war was to vote against one’s president.

At about this time, James Ewing (1744-1823), the former Mayor of Trenton, had composed a letter to John Lambert dated June 4, 1812. (Ewing appears to have had some sort of business relationship with Lambert.) It may have been received about the time the House and Senate were voting on whether to declare war. The letter reads:

John Lambert Esq.

Dear Sir

Presuming you would shortly return from Washington I am inclined to think that I did not advise you that in the 18th April I made my quarterly returns to the Treasury of the United States in which was included your unclaimed dividend for the quarter ending June 30, 1811 which you may probably receive at the Treasury before you return.

A few days ago I received the President’s Message with Barlor’s [?] correspondence for which you have my sincere thanks — We are here informed that yesterday or this day war would be declared—from which may God preserve us.

I am Dear Sir

Your most obd’ Serv’t

Jas. Ewing.”9

Even although he knew how the Senate would vote (the Senate concurred with the House with a vote of 19 to 13), Lambert could not bring himself to vote with his party to declare war. The vote in the Senate took place on June 17, 1812. Not a single Federalist voted for declaring war. Lambert was the only member of the Republican party in the Senate to vote no. Only three Republicans in the House voted no (Adam Boyd, Thomas Newbold, and Jacob Hufty). Madison signed the declaration into law on June 18, 1812.

There would be repercussions. Because of the lop-sided vote, the Federalists began calling it “Mr. Madison’s War.” But Republicans reacted differently, seeing a vote against war as an act of submission. Carl Prince wrote:

Lambert’s fellow senator, John Condit, would get toasted in Middlesex [County] as the man who voted in favor of war, “rather than submission to the injuries heaped upon us by Great Britain.”10

But John Lambert had his reasons, which he explained in the two letters below that were saved by his descendants.

The Letter of 1812

Going to war has a tendency to polarize public opinion, and public opinion was definitely unfavorable to John Lambert. At the end of the year, Lambert wrote a letter to his nephew Captain John Lambert (1777-1828), living “near Coryell’s Ferry,” reflecting on the consequences of his vote, and justifying it.11

[To] Captain John Lambert

Near Coryell’s Ferry, N.J.

New Hope, Pa. FreeJohn Lambert

Monday morning, Washington, December 14, 1812Dear Sir,

I send you two more “Auroras.”12 I don’t hear from any of my old friends in Amwell, except from home and once from your uncle Gershom and yourself. I have not had a single line from your father or Wilson.13

I know that my vote against war hath displeased those with whom I used to act. All I can say is that I believe that I was acting for the best interests of my country. I did not believe that we ought to declare war until we was ready and no other alternative consistent with our rights and the Liberty of our country could have been obtained.

That we was not ready might be seen by everyone that will divest himself of prejudice and party feelings. Our forces hath not been sufficient to penetrate Canada.

But I will not trouble you with my thoughts on our political situation. I know that I have made myself obnoxious and hateful to my old friends [the Jeffersonian-Republicans] by being true to my country. When they get the film from before their eyes they will think better of my conduct. They need not lay the change in our state to me. It is the conduct of the war party hath us down and the 14th. Congress will show more what the still voice of the people is if they are suffered to express their opinions.

Although I have lost the happiness of sociability and friendship I used to have amongst you I retain one consolation, the approbation of my own conscience. I am in middling good health and hope these may find you and yours well. Give my love to Polly and daughters.

I am yours &c John Lambert

[to] Capt. John Lambert

My heart sank when I read the sentence above: “I will not trouble you with my thoughts on our political situation.” How I wish he had.

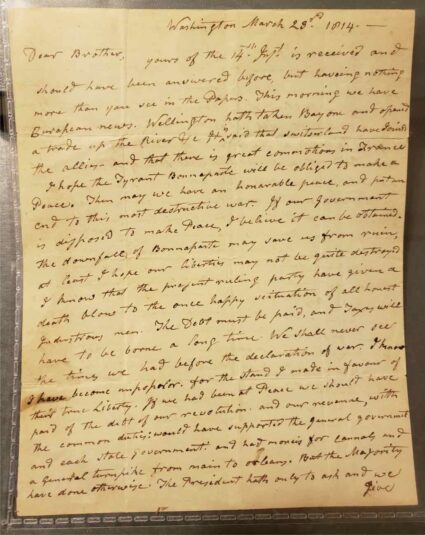

The Letter of March 23, 1814

In March 1814, John Lambert was still in Washington, DC, serving out the last year of his term as U.S. Senator. However, things were getting uncomfortable with the country operating under a wartime economy. With this in mind, he was prompted to send a letter to his brother Joseph advising him of steps to take under the circumstances.14

Here is my transcription of the letter, which includes Sen. Lambert’s peculiar spelling. During this period of time, even a well-educated man like the Senator from Amwell was casual, to say the least, about how he spelled words.

Washington March 23rd 1814

Dear Brother,

your[s] of the 14th Inst. is received and should have been answered before, but haveing nothing more than you see in the Papers. This morning we have European news. Wellington hath taken Bayone and opened a trade up the River &c It is said that switserland have Joind the allies and that there is great commotions in France I hope the Tyrant Bonnaparte will be obliged to make a Peace. Then may we have an honarable peace, and put an end to this most destructive war. If our government is disposed to make Peace, I believe it can be obtained. The downfall of Bonnaparte may save us from ruin, at least I hope our Liberties may not be quite destroyed.

I know that the present ruling party have given a death blow to the once happy scituation of all honest Industrious men. The Debt must be paid, and Taxes will have to be borne a long time. We shall never see the times we had before the declaration of war. I know I have become unpopular. for the stand I made in favour of their true Liberty. If we had been at Peace we should have paid of the debt of our revolution. and our revenue, with the common duties: would have supported the general government and each state government: and had monies for cannals and a general turnpike from main to orleans. But the Majority have done otherwise. The President hath only to ask and we give to the extent of his wishes.

I will quit

However, he did not quit, not until the end of his term, which as it happened, was at the end of the War.

Transportation from the capital to Hunterdon County in 1814 was arduous and very time-consuming, which meant that Lambert was unable to oversee his affairs while serving in the Senate. He had to leave matters to his brother Joseph, who lived in Coryell’s Ferry but also owned a large amount of real estate surrounding the village. In the early 1790s, Joseph Lambert purchased the ferry and ferry lot from the Coryell family. But by 1814, a bridge was under construction to replace the old ferry, and Joseph Lambert was very much involved in its financing and construction. It was a golden opportunity to make some money selling empty lots close to the future bridge’s location.

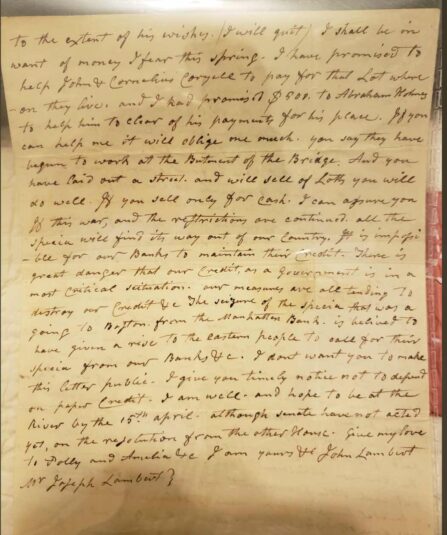

John Lambert had a particular reason for writing to his brother at this time — he needed money, and he had advice about how to get it. The letter continues:

I shall be in want of money I fear this spring. I have promised to hep [sic] John & Cornelius Coryell to pay for that Lot where on they live, and I had promised $500 to Abraham Holmes to help him to clear of his payments for his place. If you can help me it will oblige me much. you say they have begun to work at the Butment of the Bridge. And you have laid out a street. and will sell of Lotts you will do well. If you sell only for cash. I can assure you If this war, and the restrictions are continued. all the special [specie] will find its way out of our Country. It is impossible for our Banks to maintain their Credit.

There is great danger that our Credit, as a Government is in a most critical situation. our measures are all tending to destroy our Credit &c The seizure of the specia [specie] that was a going to Boston from the Manhatten Bank. is believed to have given a rise to the eastern people to call for their specia from our Banks &c. I dont want you to make this letter public. I give you timely notice not to depend on paper Credit.

Lambert was looking forward to the time when he would be able to leave Washington and return to Amwell.

I am well and hope to be at the River by the 15th April, although senate have not acted yet, on the resolution from the other House. Give my love to Polly and Amelia &c I am your &c John Lambert

Lambert succeeded in getting out of town before summer, and it’s a good thing he did. In August 1814 the British decided to make a point by burning the White House, the Capitol and other governmental buildings. But at the same time, Britain and the United States, both being tired of a war that appeared to have no end, began to negotiate, and by the end of the year had an agreement. But before the Treaty of Ghent was signed, New Jersey had another election to deal with.15

The Election of 1814

This turned out to be the last chapter in the political career of John Lambert. It was the “legislative struggle for a United States Senate seat” in 1814, which Carl Prince described as “a classic example of caucus politics at its best.”16 It seems to me a case of caucus politics at its worst.

The Republican caucus, meeting prior to the Joint Meeting in October, could not agree on a candidate. James J. Wilson, prominent politician and newspaper editor, got 16 votes, while Mahlon Dickerson, a justice on the NJ Supreme Court, got 13, with one abstention. The usual practice was for the losing voters to switch to the winning side, to make it look nice. But that did not happen in this case: nine of the Dickerson voters would not change their votes, probably because Wilson was something of a polarizing figure.

Meanwhile, the Federalist candidate was none other than former (and now scorned) Republican, John Lambert. One has to wonder how actively Lambert promoted himself or if he followed the usual practice and let his supporters do that work for him. Whatever, it wasn’t enough. As Carl Prince wrote, “Ballot after ballot was taken with the same results: twenty-three for Lambert, twenty-one for Wilson, and nine for Dickerson.”

Wilson’s supporters proposed that the lowest vote-getter be dropped from subsequent votes, a practice that was usual procedure in the past. But the Dickerson voters joined with the Federalists to defeat it. The legislature was stalemated and had to postpone the election until the next session in February 1815.

Also, unlike the usual practice, Dickerson actively worked during the interim to win over Republican voters, but without any luck. By the time the legislature reconvened, Dickerson had to bow to the pressure that Republicans applied and withdrew, allowing Wilson to win the election, and John Lambert to retire. (It just so happened that when Sen. John Condit’s term ended in 1817, the legislature gave the seat to Mahlon Dickerson.)

I can imagine there is much more to the story of how the party that John Lambert had led and supported for so many years turned against him over one vote. He managed one last gesture before leaving the Senate. On December 21, 1814, he got a new post office for Coryell’s Ferry named Amwell, with nephew John Lambert as Postmaster. The name was later changed to Lambert’s Ville, and later still, shortened to Lambertsville. However, there were certain folks, probably Republicans, who preferred the name “Lambertsvillainy.”

John Lambert died on February 4, 1823 at the age of 76, at his home on Seabrook Road in today’s Delaware Township, overlooking the City that bears his name. In its issue of March 10, 1823, the Trenton Federalist wrote:

DIED, Lately at Amwell, in this county, John Lambert, esq. formerly and for many years a member of the Legislative-Council of this state and subsequently Representative to Congress and member of the Senate of the United States.

Footnotes:

- I have written about him so often in the past, that listing the articles he appeared in here would not make sense. To see a list, click on “John Lambert” in the right-hand column under Topics. ↩

- Quoted in Henrietta Van Syckle and Emily Abbott Nordfeldt, The Lamberts of Amwell, 1976. ↩

- It is said that the number of active Loyalists in the Middle States was higher than elsewhere, somewhere around 20%. Many more, like Quakers, simply preferred to stay out of the conflict. ↩

- Carl E. Prince, New Jersey’s Jeffersonian Republicans; The Genesis of an Early Party Machine, 1789-1817, Univ. of No. Carolina Press, 1964, 1967 and Walter R. Fee, The Transition from Aristocracy to Democracy in New Jersey, 1789-1829, Somerset Press, Somerville, NJ, 1933, pp. 129-131. See also “Aristocratical Stocktons” and The Governors of New Jersey, Biographical Essays, revised & updated, by Michael J. Birkner, Donald Linky and Peter Mickulas, Rutgers Univ. Press, 2014. ↩

- Prince wrote, on p.129, that Lambert was “new on the slate of Congressional candidates” for the Republican convention of 1806 that met at Trenton on Sept. 17th. The other two new ones were Ezra Darby and Thomas Newbold. Being renewed for another term were Henry Southard and Wm. Helms. But Lambert had been elected in 1804 and was a member of the Ninth Congress that began on March 4, 1805. ↩

- See Prince, p.153. ↩

- From the Trenton Federalist, vol. X #506, p. 3. ↩

- The Boston Globe, 2014. ↩

- Letter included in a collection of papers held by the Monmouth County Historical Society. Other sources of papers relating to Lambert can be found at Rutgers University Library in the Holmes Family Collection, the Emma Finney Welch Collection at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Hunterdon County Court documents at the County Clerk’s Office, and the Hunterdon County Historical Society Archives. ↩

- Prince, p.171. ↩

- Captain John Lambert was the son of Sen. Lambert’s brother Joseph, and son-in-law of Capt. David Johnes. (See “Thomas Jones v. David Johnes”). A transcription of Lambert’s letter was published in a booklet called The Lamberts of Amwell by Henrietta Van Syckle and Emily Abbott Nordfeldt, 1976. ↩

- Most likely The Weekly Aurora, published in Philadelphia from 1810 to sometime in the 1820s. ↩

- Wilson was John Lambert’s son-in-law, William Wilson (1781-1865), future member of the NJ State Senate. ↩

- A copy of the letter was sent to me by Joe Donnelly of Bucks County, who got it from Brian Murphy, a Bucks County historian who shared it to the Bucks County History Group on Facebook with the title: “The downfall of Bonnaparte may save us from ruin.” The original of the letter was found by Brian Murphy in a Lambertville antique store many years ago. ↩

- Image from The Library of Congress; used in article by Ted Widmer, “The War of 1812? Don’t Remind Me,” 2014, Boston Globe. ↩

- Prince, p. 211. ↩