Some time ago, I made reference to the map of the Delaware River prepared by Reading Howell. Some people pointed out to me that Howell had made such a map in 1792, but were surprised by the date 1785. I had seen a copy of that map but had been unable to find it in my papers—that is, until today, when I found a very nice copy among the news clippings and other items saved by Edna Laszlo of Raven Rock. I am sorry to say, there was no notation explaining where the original map is kept.

I had mentioned the map because it was such early evidence of the presence of the Quinby family at Bull’s Island, even though the name was spelled Quimby on the map. Now that I have rediscovered it, I am delighted to share Howell’s explanation here along with the pertinent section of the map.

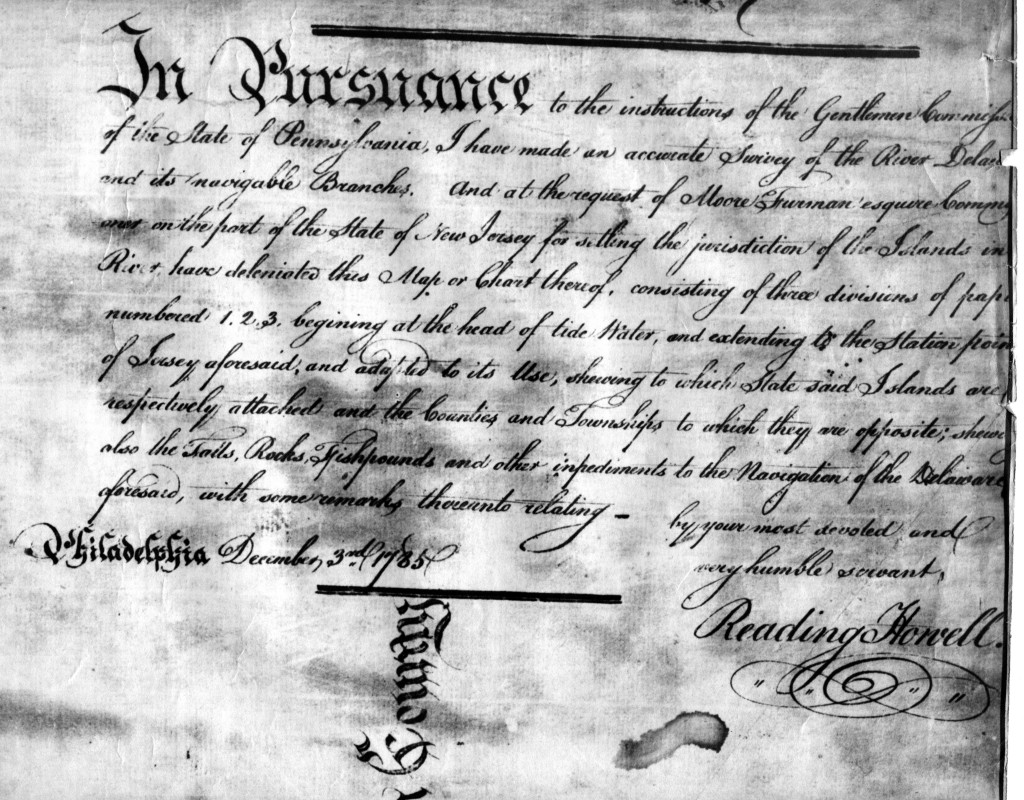

To save your eyes, here is what Howell wrote, with original spelling preserved:

“In Pursuance to the instructions of the Gentlemen Commissioners of the State of Pennsylvania, I have made an accurate survey of the River Delaware and its navigable Branches, And at the request of Moore Furman esquire Commissioner on the part of the State of New Jersey for setling the Jurisdiction of the Islands in River have delineated this Map or Chart thereof, consisting of three divisions of paper numbered 1, 2, 3 beginning at the head of tide Water, and extending to the Station point of Jersey aforesaid, and adapted to its Use, showing to which State said Islands are respectively attached and the Counties and Townships to which they are opposite; showing also the Falls, Rocks, Fish pounds, and other impediments to the Navigation of the Delaware aforesaid, with some remarks thereunto relating. — by your most devoted and very humble servant, Reading Howell

Philadelphia, December 3rd 1785”

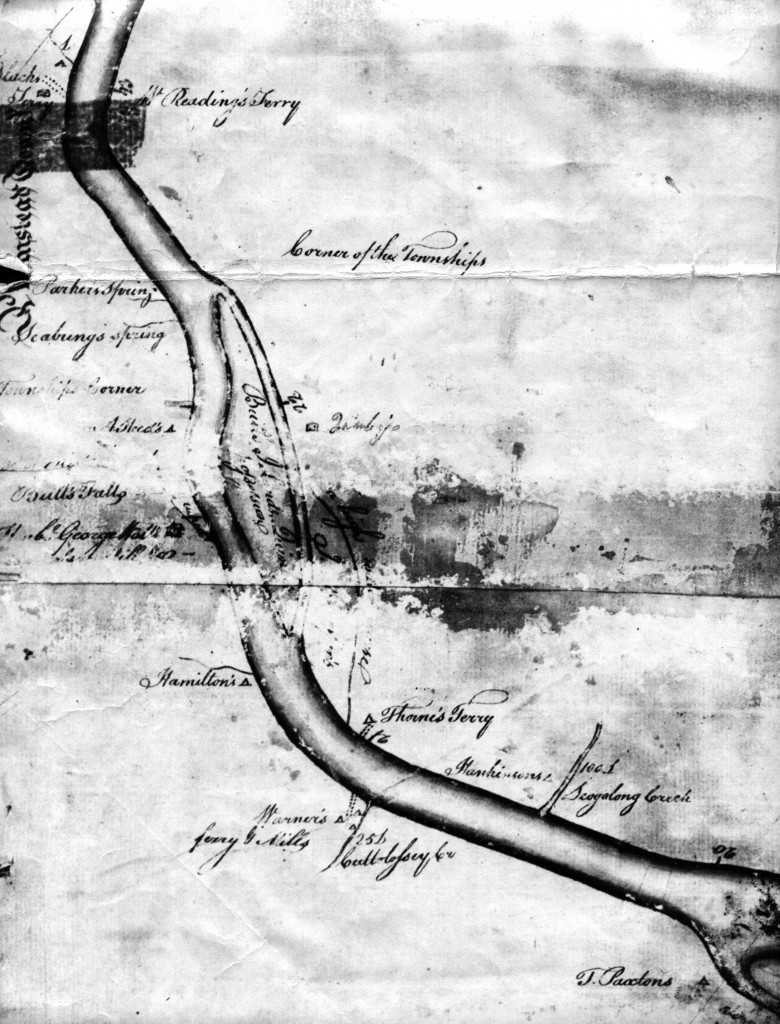

The copy in Mrs. Laszlo’s files was no doubt made from paper No. 2, although it was not labeled. Here is the section of the map showing Bull’s Island:

Granted, it’s not the easiest map to read, but it is full of fascinating information. Near the top of Bull’s Island, on the New Jersey side, is this: “Corner of the Townships.” This refers to the point where Kingwood and Amwell Townships meet at the river. North of that is “Reading’s Ferry.” This was owned by Joseph Reading Esq., who bequeathed it to his son Samuel Reading in 1806, although Samuel had probably been living there since the date of his marriage to Eleanor Anderson in 1793.

Directly across the river from Quimby, and it is very hard to see from this copy, is “A. Heed.” This would be Abraham Heed, gunsmith of Plumstead, who was often involved in Hunterdon County matters. He bought 122 acres from Joseph Reading in 1802.

Further down on the Pennsylvania side, below “Bulls’ Falls,” is George Wall, who established the village of Lumberville, PA, and later, in 1801, bought Bull’s Island from Moses Quinby and ran the fishery there.

What is most intriguing to me is that Howell has shown a house (the small square) next to “Quimby.” This suggests to me that Moses Quinby had more than just a house in that location; it suggests (and only suggests) that Quinby had already taken up store-keeping by 1785.

Also intriguing is a road that leads inland from the Bull’s Island, a short distance south of Quimby. Then it turns south and comes back to the river at Thorne’s Ferry. The only existing roads that could match that configuration are Quarry Road connecting with the lower part of Federal Twist Road.

The ferry, indicated as “Thorne’s Ferry” on the map, was located near the spot where Federal Twist Road meets Highway 29, and was run from there across the river to Lumberville. It was owned by Jacob McClain from 1775 to 1785. When Federal Twist Road was surveyed in 1775, it began at “Jacob McClain’s Ferry on the Delaware River.” There is much more to say about this ferry, which will appear in a future post, Painter’s Ferry.

Going south along the river from Thorne’s ferry is “Hankinson’s.” That is a small stone house still standing today that was part of a farm owned by Thomas Hankinson and wife Jemima Stout. In 1781, ferryman Thomas Rose/Ross gave a mortgage to his neighbor, Thomas Hankinson, who wrote his will on May 7, 1784 and died the following year. He left all his real estate to his son William, who had not yet turned 21. Jemima Hankinson remained at the farm, and when she died in 1794, her estate was administered by her brother-in-law Joseph Hankinson of Readington. Included in her inventory was a shad fishery.

After William Hankinson came of age, he sold the property to Joseph Huffman in 1804. Much to my dismay, the deed (Book 12 page 5) is missing from the Hunterdon County Clerk’s Office.

Next to Hankinson’s is what looks like “Seyolong Creek.” It is actually Lockatong Creek, which was often called Laogaland or other variants. In fact, there were so many variants, that I can only conclude that the actual Lenape name for the creek was just too hard for English ears to understand.

So, that is the Reading Howell Map of 1785. My blessings upon Mrs. Laszlo, who died nearly 20 years ago. She was devoted to Raven Rock history and did all she could to help preserve the historic character of her beloved village.

Jerseyman

February 1, 2012 @ 11:07 pm

Marfy:

If my memory is correct, the original 1785 Howell map can be found at the Pennsylvania State Archives in Harrisburg, perhaps as part of Record Group 17.

Best regards,

Jerseyman

Steve_Robbins

September 3, 2012 @ 3:47 pm

In response to the comment from Jerseyman, above, an original of the Howell Map of 1785 is also located in the New Jersey Archives in Trenton.

Howell prepared the map pursuant to a joint cooperative contract undertaken between the sovereign states of Pennsylvania and New Jersey, obviously during the pendency of that “firm league of friendship” embodied in the “Articles of Confederation”, which had gone into effect in November of 1781.

The New Jersey copy of the map was preserved nearly two centuries later, sometime in 1980 or ’81, having been wrapped in “Mylar,” and rolled on a drum.

Here is a link to a digital image of a key portion of that map that I took, depicting an area just south of Coryell’s Ferry. It shows (in the lower left) the historically famous island on the Pennsylvania side which is most often referred to as “Malta Island.” The tip of what is presently called “Louis Island” can be seen in the upper right corner.

Over time, and obviously well after this map was drawn, the gradual industrialization and “walling” along the Pennsylvania side, including as well the digging of the canal on the PA side, and later the building of wing dam south of New Hope and Lambertville, all figured in significantly changing the landscape in an around Malta Island over the years. But the remnants of that island can still be seen today along the shoreline, beginning about 1/4 mile or so, south of New Hope.

According to several historians, behind that then-heavily wooded island, was where Gen’l George Washington had a large cache of the Durham boats (and other craft) hidden, prior to the famous Christmas Crossing in 1776.

As we all know, whilst in full retreat across New Jersey in the fall of ’76, and following his disastrous defeats at a few encounters in New York, and then again in Fort Lee, New Jersey, Washington managed to think ahead, and around December 1st, at New Brunswick, he launched the brilliant military stroke of ordering Colonel Richard Humpton to go ahead and gather the boats on the New Jersey side of the Delaware, and take them over to the ferry locations on the Pennsylvania side. For their part, the Hunterdon Militia, and in particular Captains Daniel Bray, Jacob Gebhart, and Thomas Jones thoroughly scoured the NJ side from “Trenton Falls,” all the way up to the Lehigh River, gathering boats in NJ and removing them to locations on the PA side. And further south, that task was largely performed by the Pennsylvania Navy under Captain Thomas Houghton, on orders from the Pennsylvania Council of Safety. (“Washington’s Crossing,” David Hackett Fischer, Oxford University Press, New York, NY, copyright 2004, p. 134.)

Overall, of course, the purpose of the defensive measure was to stop the British Army at Trenton, primarily so that they could not cross and march on the nation’s capitol in Philadelphia, where they could have routed the Continental Congress, and thereby effectively end the “rebellion.” Washington’s Army crossed to safety from Trenton, but the British could not follow.

The Continental Army was alarmingly depleted in numbers, a situation which Washington feared was about to get much worse with the end of enlistments at the end of the year, and exhausted and ill-supplied from the retreat, they would have been incapable of stopping a British advance on Philadelphia.

Elements of the the British Army under Charles Cornwallis indeed conducted a search for the boats, including searching in and around the lower portion of Hunterdon County between the 9th and the 14th of December, including in Coryell’s Ferry, or what is now known Lambertville.

They came up empty, concluding that the boats had been “destroyed or hidden”, but as we all know, with significant Continental Army reinforcements gained during the month, on Christmas Day “night” of that December, the boats hidden behind Malta would be floated down to McConkey’s and used to launch the surprise attack on Trenton, as well as the subsequent attack on Princeton, one week later.

Malta Island was also a critical link in the flow of commerce along the river back then. As everyone who has visited the area knows, rocky falls and shoals — then known as Wells Falls — dominated the river-scape between the two states, as the river drops down several feet over a relatively short course.

Malta Island ran alongside those falls, and a “race,” or watercourse, ran down swiftly behind the island and the PA shoreline, and over a considerable distance. Rocks and obstructions were obviously kept relatively clear within that race, and boats, rafts and other commercial watercraft headed mostly toward Philadelphia could “run” the race without the high risk of crashing on the rocks of Wells Falls. Malta Island and the corresponding “race” behind it were quite lengthy. It was so long, as a matter of fact, that the race was known locally as the “Horserace.”

That last delightful little bit of information (about the local name) is duly recorded on Reading Howell’s map of the Delaware.