It is already January 26, in this 350th year of the existence of New Jersey. I think it is time to publish a short history of New Jersey, the sort of preamble I generally use for my house histories. It glides breezily over some very complicated proceedings, but sometimes a shorthand version is useful. (This little essay is not meant for those who make a study of New Jersey’s convoluted history.)

So—without more ado—How New Jersey Began.

Charles II of England was restored to his throne in 1660 following the downfall of the Puritan Commonwealth led by Oliver Cromwell. The king and his supporters had been in the wilderness so long, they were hungry for the perquisites of power, including the ability to wage war and exploit colonies. Among those supporters was the king’s brother James Duke of York, who was made Admiral of the English Navy.

James had his eye on North America. The Colony of New England was beginning to prosper since the Pilgrims settled there in 1620 and the Puritans in 1630. Also, the Virginia Colony had survived “the starving time,” and was now exporting tobacco. But in between lay the Province of New Netherland, owned by the Dutch. The English and the Dutch did not get along in the 17th century—they were aggressive competitors in the new international world of trade. They frequently went to war over inconsequential disputes. The first war took place in 1652-54. Ten years later, the English thought it was time for another attack, an opening to the Second Anglo-Dutch War which ended with a treaty in 1667.

James had been informed it would not take much to oust the Dutch from the Atlantic coast of North America. All he would need was 3 ships, 300 soldiers and 1300 colonials. So, he persuaded his brother to undertake the adventure and the king promptly ordered an expedition, led by Col. Richard Nichols. In April, while Nichols was still at sea, Charles was so certain of success that he granted the whole province to his brother James. As part of this grant, James was given the right to name the Governors, Officers & Ministers as he should see fit; also to make laws, so long as they “bee not contrary to but as neare as conveniently may bee agreeable to the Lawes Statutes & government of this our Realme of England.” The king threw in £4,000 to help pay for the effort.1

The conquest went off without a hitch. The Dutch Governor Stuyvesant, realizing he had not the wherewithal to defeat an English mini-armada, decided to surrender–without a shot. The English moved in under the temporary administration of Col. Nichols. (Ironically, Dutch residents of this new English colony prospered more than they had under Dutch rule.)

Getting back to Charles’ gift of New Netherland to his brother–this simple act created a host of legal difficulties for the new English colony. And James complicated it further. Unbeknownst to Col. Nichols, who was making land grants and waiting for word back from England on how to proceed, James decided in June 1664 to give the whole province of Nova Caesarea, also known as New Jersey, to two men who had supported his brother during the Protectorate of Oliver Cromwell. These two gentlemen were Sir George Carteret and John Lord Berkeley. The name New Jersey was meant to honor Carteret whose home was the Isle of Jersey. There was nothing in Charles’ grant to James about handing over the whole thing to anyone else, but James seems to have thought he was entitled to do this. However, he did not give away New York.

This fact, of James granting New Jersey to Carteret and Berkeley, is always mentioned in histories of the state. But not so often mentioned is the fact that Carteret and Berkeley were members of the special committee that had been asked to investigate “the Amsterdam situation” well before the attack on New Netherland was ordered, and had strongly recommended it. Also, that Berkeley was president of the Council on Foreign Plantations, and Carteret was Treasurer of the Royal Navy.2

Neither Carteret nor Berkeley had any interest in settling in the New World—they were too comfortable in the old one. But George Carteret did send his nephew Philip Carteret to act as Governor on his behalf. He landed in New Jersey in August 1665 and with the few immigrants who sailed with him, set up a new settlement in Elizabeth Town, named for Sir George Carteret’s wife. But others had already begun to settle in what became known as the Province of East New Jersey. These were the people who had gotten grants from Col. Nichols in 1664. Serious conflicts over ownership soon developed, but since my focus is on West New Jersey, I will leave this story untold.

In 1673, as part of a new Anglo-Dutch War, the Dutch returned to New Netherland and retook the province. This was a very short war. By February 1674, a new peace treaty was signed in which New Netherland was returned to the English, and the Dutch got Surinam, a far more profitable colony.

This business seems to have convinced Lord Berkeley that owning half of New Jersey was more trouble than it was worth. He was growing old and did not expect to see any profit from it, so he offered his share for sale to an acquaintance named Edward Byllinge. At the time, Byllinge’s finances were in disarray. He seems to have thought such a purchase would be a good way to solve his problems, but he needed a front man to act as buyer. That turned out to be fellow Quaker John Fenwick who in the spring of 1674 paid £1,000 for the half share of New Jersey, “in trust for Edward Byllinge.”

Fenwick happened to be one of Byllinge’s creditors. He thought the whole purchase should belong to him, despite that phrase ‘in trust for . . .’. Byllinge and Fenwick were persuaded that their dispute should be resolved in the Quaker way, which was to let some impartial fellow-Quakers arbitrate for them. (It was important for this persecuted sect to stay out of English courts as much as possible.) The Quakers who were chosen to negotiate the agreement were William Penn, Gawen Lawrie and Nicholas Lucas. They divided the Berkeley-Byllinge share of New Jersey into tenths, giving one tenth to Fenwick and putting the other nine tenths up for sale, the proceeds to be partially used to settle Byllinge’s debts.

Here is where it gets complicated.

This whole business of shares in the Province makes little sense to us today. We are accustomed to pretty straight-forward land transactions in which the owner of a property sells it to someone else. But in the late 1600s people did not own land outright in New Jersey. The shares they had in the Province entitled them to surveys of land, once it was determined to issue a dividend to the shareholders. The shareholders were known as Proprietors, and the land system was a proprietary system. Once the survey was recorded, the owner of that abstract thing known as a share, became an owner of that concrete thing, title to real property.3

William Penn was a follower of George Fox and shared the dream of founding a Quaker colony in the New World. Fox had visited the middle colonies in 1671, and had actually traveled across today’s New Jersey, which must have been a very arduous trip. With the acquisition of Edward Byllinge’s share of New Jersey, William Penn saw a golden opportunity to carry out Fox’s dream. Although Penn was just one of many shareholders, “West Jersey, not Pennsylvania, was Penn’s first Quaker colony.” 4 Penn, Lawrie and Lucas encouraged settlement of the western portion of the province, starting at the mouth of the Delaware River, away from the well-established eastern towns and the influence of Sir George Carteret.

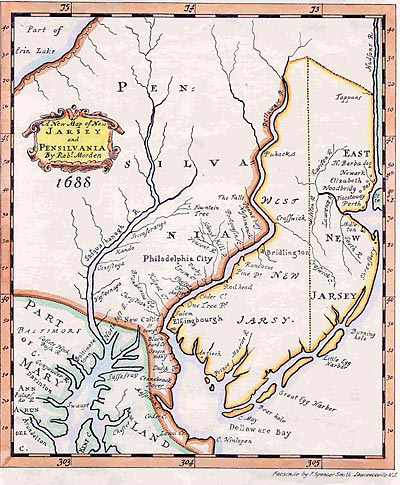

Carteret’s interest in New Jersey was recognized by the Duke of York, but the Fenwick-Byllinge arrangement was not, mostly for political reasons, and probably because this was primarily a Quaker settlement. To clear things up, William Penn and the other trustees began long negotiations with Carteret which ended on July 1, 1676, with the signing of the Quintipartite Deed. This document essentially divided the province into an East Jersey for Carteret and a West Jersey for the Quakers, with a line running from Little Egg Harbor on the Atlantic to the province’s northwest corner on the Delaware River.

It was also in 1676 that Byllinge and Penn wrote “The Concessions and Agreements of the Proprietors, Freeholder and Inhabitants of West Jersey in America,” placing the governing power in a representative assembly. At that time, they divided each of the Tenths further into tenths, creating one hundred shares or “proprieties.” A few of these shares, or 100ths, were allotted to Byllinge and the rest were sold, mostly to other Quakers.

English settlement of “The Province of West Jersey” began in earnest in the 1670’s in Salem, Gloucester and Burlington Counties along the Delaware River. Even though some English settlers claimed that their title to the land was sufficient through the King of England, the Quakers who controlled settlement of West Jersey insisted that the land be formally purchased from the resident Indians. This helped to maintain good relations with them and helped the Quakers to secure their legitimate ownership.

Thus, the way was cleared for settlement in a new land. For a short time, the Quakers realized their dream of living apart from the onerous government of England that had treated them so harshly. But such dreams never last long, and West New Jersey soon found itself struggling to remain free of English domination, while remaining part of the realm. However, increased interference from the king’s officers did not deter settlers, who inexorably explored and settled on the lands along the Delaware River. But they did meet with an obstacle—the Pine Barrens. Settlement eastward into the center of New Jersey was brought to a halt by this huge area so unsuitable for agriculture and forced it northward along the river until the very fertile central section, known as the Piedmont, was reached.

Once that happened, proprietors clamored for another division of land. But that could not be done without some major Indian purchases, which will be discussed in the next installment.

——————————————-

I have two reasons for publishing this article. As mentioned above, I want to acknowledge and celebrate the 350th year of New Jersey’s existence. Secondly, I am embarking on something new for me. I am going to publish a house history that I am currently working on (and expect to finish soon). The owner has given his permission, and I thought it would be worthwhile because the various former owners of this property are of considerable interest to Delaware Township history.

Every house history I do starts with something similar to this short history of New Jersey’s colonization (although slightly different each time). The intention for each of my house histories is to get back to the beginning, and, excepting the native Americans, English colonization is the beginning, at least for Hunterdon County.

The next chapter in this saga is the Adlord Bowde Purchase and the life of Richard Bull, which have already been published. Next to come is Richard Bull’s sister Sarah Bull, wife of Samuel Green. For a list of articles in this series, please visit the Index of Articles Page.

Update, 1/27/14: My chief editor observed that I seemed to imply that William Penn owned the province of West New Jersey, or at least had taken charge of it. I have reworded a little to avoid that impression.

Footnotes:

- Charles A. Weslager. The English on the Delaware, 1610-1682. 2nd, 1969th ed. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1967, p. 182. ↩

- John Pomfret, Colonial New Jersey, A History. NY: Charles Scribners Sons, 1973, p. 4-5. ↩

- For a good description of this odd arrangement, see “Using the Records of East and West Jersey Proprietors” by Joseph Klett, New Jersey State Archives 2008, available on the Archives website. ↩

- Charles A. Stansfield, New Jersey, A Geography, Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1983, pg 18. ↩

Diane Hearne

January 26, 2014 @ 2:17 pm

Excellent article – as always. Thank you so much!

(My Welch family – William, Abner etc. were Quakers for a while!)

phoebe wiley

January 26, 2014 @ 3:11 pm

fascinating article!

always interesting with lots of new information

and timely

thanks

Phoebe

John Brady

January 27, 2014 @ 10:55 am

Marfy – Thanks for sharing all the nuances of the players and story behind the story. These details really fill in many significant gaps in the critical yet often murky 1670’s. I believe the mapmaker is Robert Morden, published 1687 in London.

Alberta James Daw

January 27, 2014 @ 2:33 pm

Thank you, Marfie. This is history that I had not known before.

Bertie (Alberta)

Marfy This Month | Hunterdon County Historical Society

February 1, 2014 @ 1:00 am

[…] everyone, I have just published a short history of New Jersey’s beginnings How New Jersey Began and a strange tale it […]

William Van Natta

March 23, 2014 @ 6:25 am

Thank you for this concise story of New Jersey.