Now the fun begins–the 1826 Celebration of the Fourth of July in Flemington, NJ. (Part Two of the reprint of my article in the Hunterdon Historical Newsletter, Spring 2006. You can read Part One here.)

The various military companies lined up for the procession, followed by “the Jackson band of music,” a standard bearer, members of the clergy, the orator of the day, the day’s reader of the Declaration, and the Committee of Arrangements. These were followed by a “choir of 13 females dressed in white” representing the original 13 states, and a younger group of 11 women, all wearing badges with the names of the remaining states. (There were 24 in 1826.) Then came “a great assemblage of females from all parts of the country” and they were followed by “an immense concourse of citizens and strangers.” One wonders who was left to watch the parade. It is also very interesting that so many women took part, as it was generally rare for women to participate in public demonstrations.

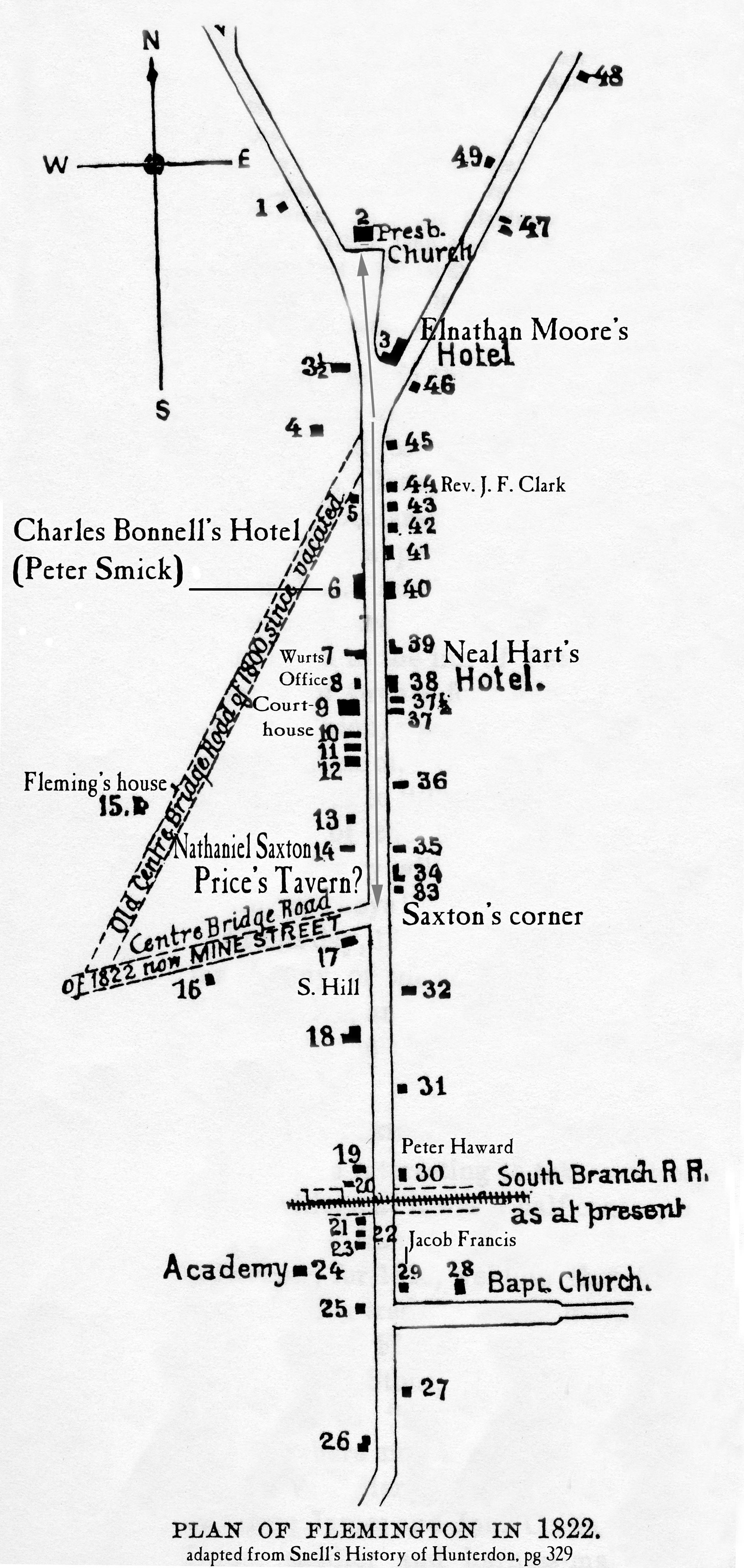

Starting from Gen. Price’s House near Mine Street, the parade marched to the Presbyterian church to the tune of “Hail Columbia.”1 Charles George observed that the band continued playing until “the whole audience were seated in the church.” The church was well-prepared for the great event, decorated with “large wreaths of laurel” which “encircled the whole interior of the building.” The pillars were “most delicately entwined with the richest of the Evergreen, while the Holy altar was literally embowered with all that could delight the eye or gratify the taste; the whole being studded with the richest and choicest of the flowers of the forest and garden.” Both prose and church were heavily ’embowered.’2

After an invocation by Rev. John F. Clark, and a song from the choir, the Declaration was read by Alexander Wurts, followed by another “ode from the choir.” Then the Orator of the day, Andrew Miller, gave his speech, with a concluding acknowledgement of the veterans. As Charles George wrote:

“Upon their being especially addressed by him, they spontaneously rose in their seats, and continued standing with the most fixed and solemn attention. Few witnessed this scene without emotion. This corps was assembled for the first time since the revolution, and to-day they came out to test their love of country, and to bequeath afresh the inheritance that they had so dearly purchased.”3

At this point, the editor remarked that “however a niggardly economy on their part may withhold from the poor old soldier a bare living, the voice of the people awards to him a generous support.” He was referring to the failure of Congress during its last session to pay the debts due to the veterans.4

After another song and the benediction, the procession reassembled and marched to the accompaniment of the Jackson band to “the house of Mr. Peter Smick.” Once there, a 24-gun salute was given, one round for each of the states of the Union. Then the old veterans were treated to a meal by Mr. Smick, during which time they recalled their wartime experiences. After the veterans had finished their dinner, “a large company” sat down to eat at 3 p.m. in Mr. Smick’s tastefully decorated dining room. (Presumably the rest went home to eat.) In keeping with a tendency to appoint officers for any and all occasions, a “President of the table” was named (veteran Jacob Anderson, Esq.) and for good measure, a Vice President (George Maxwell, Esq.). Exactly what their responsibilities were is hard to say, unless it involved maintaining proper decorum. Once the dinner had finished, “the cloth was removed” and the toasting began.

As was customary, 13 toasts were given, by persons unnamed in the Gazette. The subjects were: The Day, The Federal Union, {George} Washington, The Remnant of 1776, The Jubilee, the President of the United States, The Governor of New-Jersey, The State of New-Jersey, Samuel L. Southard {Secr. of the Navy}, The Republics of South America, Greece, the new States and “Woman” (“A dish of contrarieties; but one we never tire of nor forget.”). The Gazette does not say if women were present to hear this toast, but the 13th toast was always for the women or “the Fair.”

These were followed by toasts given by “volunteers,” whom the Gazette did identify. Most were members of well-established Hunterdon families: Jacob Anderson (the president), George Maxwell (vice president), Mr. Charles Bonnell, George C. Maxwell Esq., Samuel G. Opdycke Esq., Zaccur Prall M.D., John Waterhouse Jr., Capt. H. M. Kline, Maj. Wm. Hunt, Capt. Peter I. Case, Capt. Peter Ewing, Capt. Jacob Voorhees. The newcomers were, in addition to Miller, Clark, Wurts and Blackwell already described, James H. Blackwell (son of John), Leonard N. Bowman {Boeman}, and Adams C. Davis, who was born in Vermont.

Judging by the toasts given, the sentiment was clearly with Andrew Jackson, despite his having lost the presidential election of 1824 in the House of Representatives to John Quincy Adams. Only one toast is recorded for the President, but Jackson received two by name, along with others favoring a future election. From Samuel G. Opdycke, “Gen. Andrew Jackson—defeated once, but how? That’s the question. We hope to fight that battle o’er again.” Or from Capt. Henry M. Kline: “God save the republic; but the 4th of March 1829 {when the next president would be inaugurated} will tell a tale, the resolutions of Adams brethren of Somerset {a reference to Samuel Southard} to the contrary notwithstanding.”

There was some dry humor offered by Charles Bonnell, who toasted the last session of Congress, saying: “Mr. Chairman, I move that the committee rise; I wish to publish a four hours speech on this question.”

Other subjects for toasts were the Delaware & Raritan Canal, Gen. Bolivar, the Congress at Panama, “the venerable Thomas Jefferson,” Gen. William Maxwell, Greece and Missolonghi, and by Peter I. Clark Esq., to “the Judiciary of the United States, we tremble for its extension upon the basis assumed in the last congress. Heaven protect this precious repository of our liberties from the intrusion of bold speculation.” In April 1826, Congress debated legislation to increase the number of judges on the Supreme Court from 7 to 10. The legislation, which eventually failed, was meant to deal with the huge amount of litigation coming from the western states where so many land titles were being contested.

The Delaware & Raritan Canal was still just a dream in 1826, inspired by the success of the Erie Canal, which opened in 1825. General Bolivar was leading a movement for independence of all South America from Spain. The Congress at Panama was intended to create an alliance between the newly independent South American countries and the United States (it failed).

Greece and Missolonghi were matters of interest similar to South America—the struggle of other countries to win independence from colonial powers. But Greece was a special case, with its history as the birthplace of democratic government. Missolonghi was a fortress where Greeks hoped to take a stand against the Turks; reports of its fall appeared in April 1826. The Greeks had vowed to die rather than be captured; perhaps as many as 8 to 10,000 did die.

Gen. William Maxwell was one of Hunterdon County’s genuine war heroes, in both the French and Indian War and the Revolutionary War; he died in 1796.5

The death of Thomas Jefferson on this day, as well as of John Adams, was not known to the residents of Flemington. Recall the toast given by Andrew Miller to “The venerable Thomas Jefferson.” No mention was made of it in the description of the celebration given in the Hunterdon Gazette, published on July 12th, a week after Jefferson and Adams died, other than a brief notice at the end of the story on Lambertville’s parade. A week later, lengthy stories were published about the two great men, and Charles George made these comments:

“We are not the first who have remarked the striking coincidence of events which, on the jubilee of our national independence, bereaved the country of two of its revered sires, just fifty years from the day on which they signed the Declaration of Independence. –But one of the chosen band remains—Charles Carroll of Maryland.”

After the toasts were given, a salute was fired by the Company of Infantry headed by Capt. Jacob Voorhees and Capt. Peter Ewing, followed by more music from the much-appreciated Jackson band. The editor congratulated everyone involved on a successful event, without any incident of rowdiness or rude behavior. As a former resident of Philadelphia, Charles George could appreciate the way Flemington celebrated its Jubilee. In his editorial a week later he wrote:

“This auspicious day was held, in this village, with unusual demonstrations of joy; and to a stranger it would perhaps be impossible to give an adequate expression of the kind and degree of feeling excited upon this interesting occasion. . . . There is something in a village celebration of great events, that has a character peculiar to itself. Borrowing nothing from the imposing and sometimes unmeaning pageantry of a city celebration, it exhibits the simplicity of an ardent and honest zeal to contribute her utmost to the general swell of exaltation.”6

The Celebration at “Lambertsville”

Lambertsville (as it was generally called at this time) was a different place from Flemington, although it followed the time-honored formula for July 4ths, with the proper parade, organized by a “Committee of Arrangement,” and included “a company of boys dressed for the occasion, under the care and direction of captains Lambert and Rounsavell.” Lambertville’s “ladies” were escorted to the church ahead of the rest, rather than follow as part of the parade. At the church there was

“1, an invocation to the throne of Grace by the Rev. Mr. Van Lieu; 2, an ode composed by C. B. Phillips for the occasion, was sung by an excellent choir under his direction; 3, prayer by Mr. Van Lieu; 4, another appropriate ode; 5, reading of the Declaration of Independence; 6, Hail Columbia by the band; 7, oration; 8, anthem, strike the cymbals, words adapted by C. B. Phillips; 9, Benediction by the Rev. P. O. Studdiford.”

The citizens of Lambertville were joined by those of New Hope in the parade to the church. Lambertville was more oriented to the river and its sister village on the other side, than towards the center of the county. It was a far more commercial town than Flemington, as it always had the benefit of river traffic. Lambertville seemed to feel itself in competition with Flemington which became apparent after the county courthouse in Flemington burned down in 1828. Lambertville citizens immediately began promoting the idea of moving the county seat to their town, and wrote lengthy letters to the Gazette describing the advantages of their town over Flemington’s. But when it came to the number of war veterans in its parade, Flemington won hands down, as it did with the courthouse.

After the ceremonies at the church,7 the parade returned to “the east side of the bridge.” Then the New Hope residents returned across the river, and the Lambertville residents “sat down to an excellent dinner at the hotel prepared by John S. Prall.” The Marshall of the day and president of the dinner was Major William Garrison, while Dr. John Lilly was chosen Vice president. After the cloth was removed, the toasts began. As with Flemington, the Gazette did not identify those who gave the first toasts, but did name the volunteers. They were:

From old families—Mr. Joseph Wood, Mr. John Hoppock, Dr. William Coryell, Alexander Coryell, C. B. Phillips, George W. Rittenhouse, J. B. Smith, J. W. Coryell, G. Abbott, J. Chamberlin, John H. Coryell, Capt. John Lambert, Henry Thatcher, J. Thatcher and probably Thos. Thompson. The ‘new men’ were Mr. Stewart of Philadelphia, Mr. Delavan, Capt. R. H. Knowles, and J. Ashmore. The pattern was similar to Flemington’s—the old families dominated, but new men with ambition took active roles in the life of the community.

Many toasts were given—two for “The Day we celebrate,” six for the United States or “our Government,” one for The Governor of New-Jersey, one for Dr. Geo. Holcombe, “our representative in congress,” one for The Secretary of the Navy [Samuel Southard] and one for Gen. Lafayette. Also toasted were De Witt Clinton, The Delaware and Raritan Canal, “Our South American brethren,” the Greeks, “The American Fair” and The Washington Band.

There were toasts for the war veterans and the militia, and for Thomas Jefferson and George Washington, this last one drunk standing. Andrew Jackson received six toasts, including one that hoped that “the 4th of March 1829 place him in the presidential chair.” Unlike Flemington, John Quincy Adams also received toasts. Two were disparaging, like the one from J. B. Smith: “The President of the U. States—may he learn by 4 years experience that honor gained by barter and intrigue is but a crown of thorns,” and two were actually positive. One of the positive ones was given by Henry Thatcher (“the people’s choice as elected by the constitution”) and the other by one of the unnamed original toasters (“with the happiness and prosperity of his country ever in view, he has nothing to fear from the virulent tongue of calumny, the monster of disappointed ambition.”)

One wonders what the atmosphere was like as these toasts were given. How much animosity was there between Jackson and Adams supporters? The Gazette claimed all was harmony. “The [Lambertville] company separated at an early hour, highly gratified with the entertainment of the day.”

Speaking of the Flemington event, Charles George wrote:

“It is a cause of congratulation, that though many things were encountered in the course of the day in which in rude hands there is no small risk, though the procession was perhaps the largest ever assembled in this place, and the church crowded so that many were obliged to stand during all the exercises, not a single accident occurred to mar in the least degree the good feelings which predominated on this day. Before the darkness came upon us, our village was restored to its wonted repose.”

No other July 4th would quite live up to the intensity of the one celebrated in 1826. Judging by reports in the Gazette, Flemington did not have one every year. Some years (1835-37, 1840, 1845, 1851-53) there was no celebration in Hunterdon County worth reporting.8 With the presence of so many Revolutionary War veterans, gathered together for the first time since the war had ended, the 4th of July of 1826 was a singular experience.

Independence Day was a non-partisan political holiday at which all were welcomed. But the coming years of the Jackson administration brought much tumult to Hunterdon County, as they did to the rest of the country, and this was reflected in subsequent 4th of July celebrations. Judging by the toasts given in 1826, it seems that those present had an inkling of what was coming.

Postscript, June 27, 2014: Egbert T. Bush wrote an article about Toasting the Government, to which I added some more history of the practice in Hunterdon County, and how it ended in 1860.

Footnotes:

- Columbia was the goddess of Liberty, a feminization of Columbus. ↩

- For a description of the church as it appeared in 1826, see Snell pp. 310-311; Rev. Clark had a new pulpit installed in 1827 (Snell p. 312). ↩

- For the list of names of those veterans, please see Part One of the Jubilee. ↩

- As described in an article from the New York Literary Gazette reprinted in the July 5th edition of the Gazette. ↩

- Snell p. 251. See “General William Maxwell” by John F. Schenk in Hunterdon Historical Newsletter, Vol.12, No.2, pp. 197-205. ↩

- Hunterdon Gazette, No. 69, July 12, 1926. ↩

- Since the benediction was given by Rev. Peter O. Studdiford, we can assume the church referred to was the new Presbyterian church on Union Street (see Snell pg 274-75). ↩

- According to Snell, the last one celebrated in Flemington was in 1860 (p. 324). ↩