Recently I gave a talk at the Hunterdon Co. Historical Society on how to research the history of one’s house. While preparing for the talk, I decided to look over the history I did for my own house back in 1981. It was the first one I had ever done, and I hadn’t a clue about how to go about it. I found most of the owners of my home, but some of them were absentee owners, so I didn’t pay much attention to them. On reviewing my chain of title, I got curious about one of those absentee owners, and began to do some more serious research. It paid off with a pretty interesting story.

John Prall Rittenhouse was born on May 17, 1820 to Samuel Rittenhouse and his second wife, Hannah Emmons. Samuel and Hannah were living in a stone house near the Covered Bridge in Delaware Township and were good friends with the Sergeant family who lived on the other side of the bridge. As a child, John attended Green Sergeant’s School, which was opened in 1830 by Green’s father Charles Sergeant.

Samuel Rittenhouse became one of the trustees of the Sandy Ridge Baptist Church in 1818, so that is where the family worshipped on Sundays. The church was just far enough away to require the family to pile into a wagon to get there. When Samuel and Hannah Rittenhouse died (she in 1843 and he in 1850), they were buried in the cemetery there, as were their three youngest children.1

John’s older brother, James E. Rittenhouse died at the age of 21, on Dec. 7, 1835. It was a somber occasion when this young man was buried in the Sandy Ridge Cemetery, and probably quite a shock to his younger, 15-year-old brother John. John’s only remaining sibling was his sister Martha, who was five years older. She stayed at home during his childhood and did not marry until 1842 (her husband was James Salter).

I have not discovered what John P. Rittenhouse did before 1845, the year he got married, or how he came to meet his new wife. She was Susan Ann Acker Huffman (or Hoffman), daughter of Rachel Hoffman. The identity of Susan’s father remains a mystery to me. At first I thought he might have been Levi Hoffman, son of John Hoffman of Amwell. But in fact, according to the family bible of Isaac and Susannah Rittenhouse, Susan was the daughter of Levi’s sister Rachel. And although the Bible listed marriages, there was none listed for Rachel Hoffman. The fact that Susan’s name was written as Susannah Ann Acker Hoffman should be a clue to her father’s identity, but I have not pursued it.

In 1848, James Marshall of Lambertville discovered gold in California. News of that discovery must have reached the whole country within days and ignited a wave of migration from the east coast. In a history about Marshall’s Discovery published in the Hunterdon Republican (Aug. 6, 1896), the unnamed author wrote that in 1849, John P. Rittenhouse was one of those who went to the gold fields by way of Cape Horn to “try his hand.” This is surprising given that by that time he had been married for four years. An article published about 1900 in the Hunterdon Co. Democrat described how Rittenhouse came to make that trip.2 In 1849, Rittenhouse was employed as “a shipper of produce,” and had to visit John Quick at his office in New York City. He had made up his mind to travel to California and mentioned that fact to Quick, who told him that Elisha Holcombe, who also had an office in the City, had invested in a schooner named “Olivia” and was planning to send it to California by way of Cape Horn with supplies for the miners. But Holcombe did not want to make the trip himself, and was looking for an agent. To make a long story short, Rittenhouse got the job, thanks to the intervention of one of his former pupils, Jacob Fisher.

Rittenhouse was well-liked and well-known as a great story-teller. In his later years he found a ready audience among the men who loitered in front of the Democrat’s office in Flemington. The reason for publishing the story in 1900 was that Rittenhouse had observed that during the previous week, he had attended the funerals of the three men who had enabled him to travel to California, Elisha Holcombe, John Quick and Jacob Fisher, all of whom had moved back to Hunterdon County. By that time Rittenhouse was 80 years old, and must have felt saddened to be the sole survivor.3

Rittenhouse must have gotten his work in California done quickly, for he was back home in time for the 1850 census for Raritan Township. In that census record John P. Rittenhouse was a 30-year-old farmer with no financial assets. Living with him were his wife Susan, also age 30, and his mother-in-law Rachel Huffman, age 56, with assets of $1200. I have not looked up the estate of Rachel’s father, John Hoffman, but his obituary, published in the Hunterdon Gazette on April 26, 1837, stated that he died “in Amwell, Near Buchannansville,” which was at the intersection of Routes 523 and 579, where Buchanan’s Tavern was located. It is likely that Rachel had inherited some of her father’s property and welcomed her daughter and son-in-law to live with her.4

The first newspaper notice I found for John P. Rittenhouse was dated January 11, 1854 in the Hunterdon Gazette, when his name appeared on a list of members of the Flemington Vigilant Society. By September he was named assessor of the club. A notice on Sept. 13, 1854 informed anyone with “damage done by dogs to their Sheep” in Raritan Township to present their certificates to either John P. Rittenhouse, assessor, or David Dunham, collector.

Two years later, on June 14, 1856, John P. Rittenhouse paid $850 to purchase a farm of 20.18 acres having a small house, a small barn and a carriage shed.5 This is the house I was researching back in 1981. The property was located in Delaware Township, on the Locktown-Flemington Road. It is unlikely that the Rittenhouse family moved in after the purchase. The house was intended for a tenant when it was built in late 1845, and probably did not have a residential owner until 1874.

A few months later, in October, Rittenhouse was nominated to run for the Assembly as a Democrat.6 This was the second time Rittenhouse was nominated, but this year he was successful, winning a seat in the Assembly for the 1856-57 term. (He was succeeded by a Delaware Township resident, William Sergeant.) From this point on, Rittenhouse would be able to use the title of “Hon.”, but I never saw an instance of its use. Perhaps that was his preference. While he was serving in the Assembly, Rittenhouse was named a director of The Farmers’ Mutual Fire Assurance Association of New Jersey.”7.

While still serving in the Assembly, Rittenhouse found that the property adjacent to his 20.18 acres was being offered at a Sheriff’s sale. Its owner, a single lady named Sarah Kugler, was unable to pay her bills and the property was seized by the court. Rittenhouse was the highest bidder at $550 for the 30.89-acre parcel, which he formally purchased on July 6, 1857.8 As far as I can tell, Sarah Kugler remained at the house, presumably as a tenant.

After his term in the Assembly was over, in 1858, Rittenhouse was given a political appointment that could, if he were so inclined, have made him fairly rich. Here is how the Gazette reported the story:

“John P. Rittenhouse, Esq. (familiarly known as Johnny P.) has received an appointment to the Inspectorship in the New York Custom House. He left this place on Monday morning for the city, to enter upon his duties forthwith. Throwing aside the fact that Johnny P. is a stiff Administration man, (and we suppose if he had not been, he would’nt [sic] have been.) we can pronounce this a very judicious appointment. He possesses all the requisite qualifications to fill this post with credit to the Administration and honor to himself. Success to him.”9

The Customs Office in New York City was not known for its scrupulously honest practices, but it appears that “Johnny P.” was an exception to the usual standard of employee, i.e., he was not a bribe-taker. As for the nickname, it was applied to him with affection, but these days it would certainly be cause for ridicule.

At the time that Rittenhouse got the job of Inspector, the Administration was controlled by the Democrats. So it is not surprising that he lost it after Abraham Lincoln was elected. He was back in Flemington in 1859. On April 1st of that year, John P. and Susan Rittenhouse sold the two lots of 20.18 and 30.89 acres, both of them with houses and tenants (although the tenants were not identified in the deed), to Rittenhouse’s political friend Edmund Perry of Flemington, for a total of $1,500, giving Rittenhouse a profit of only $100.10

I should note here that Edmund Perry, the next owner in my chain of title, became editor of the Democrat in 1849, and set up his law office in Flemington in 1850. He handed “The Democrat” over to Adam Bellis in 1853. By 1854, he was a recognized leader of the Democratic Party in Hunterdon County. Later in 1859, after buying the property on Locktown-Flemington Road, Perry ran successfully for the NJ State Senate. Thus, two of the owners of my property were elected to the state legislature. In 1981, by an odd coincidence, my husband won his own seat in the Assembly.

At this point, it would appear that the association of John P. Rittenhouse and the small farm on Locktown-Flemington Road had come to an end, but not quite yet. So let us continue with Rittenhouse’s biography. By this time, all of his children had been born. The first two died as infants in 1848 and 1849, and were buried at the Sandy Ridge Cemetery.

On July 14, 1860, when the census taker visited the family, John P. Rittenhouse was 40 years old with real estate worth $5,000 and personal property worth $2700—comfortable but not rich. His mother-in-law Rachel Huffman, age 60, was still given precedence in the listing over her daughter Susan; Rachel had property worth $300. The children were listed next: Hawley age 9, Albert age 7, Claude age 3 and Marion 3 months, followed by their mother Susan, age 40. Domestic help was provided by Sarah Case, age 24; farm labor was done by Smith D. Rittenhouse, age 21, born about 1839 in Maryland.11 Next to the Rittenhouse family was that of Paul K. Hoffman, age 44, with property worth $8,000. Paul was the nephew of Rachel Hoffman, and son of Isaac Hoffman and Susan Bodine.

Once the Civil War began, and as long as it continued, the Hunterdon Gazette and the Hunterdon Republican published the lists of those who had been drafted. John P. Rittenhouse’s name only appeared once, as far as I can tell. In July 1863, he was listed as a 43-year-old farmer from Raritan Township. Going by articles in the Gazette and Republican, he was never involved in any other kind of activity related to the war. Perhaps this was due to his party affiliation. It would be interesting to know how much sympathy he had, or lacked, for the Union cause as opposed to the Copperheads.12

Like everyone else, Rittenhouse did pay his Civil War Income Taxes. In 1863 he was taxed $2 on a two-horse wagon valued at $75. Apparently he did not pay the full amount—or he was late in his payment, because in the beginning of 1864 he was charged a 20-cent penalty. For 1864’s tax he was assessed $2 on his two-horse carriage again, but this time the carriage was valued as $120. The same was done in 1865, but in addition he was taxed $1 on a watch. Then in August 1866, he was listed as a “patent rights dealer,” and taxed $7.50 on whatever his income was, which was not stated.13

Rittenhouse found other ways to stay active during the War. In 1862, he was one of those chosen to represent peach growers in their meetings with railroad representatives, to work out problems of delivery.14 And Rittenhouse was one of the delegates to the Democratic State Convention held in Trenton (along with Edmund Perry and Joseph W. Wood) in the fall of 1862.15 At the 1864 meeting of the Raritan Twp. Democratic Organization, Edmund Perry was elected president of the meeting, and John P. Rittenhouse was named to the executive committee.16

A surprising incident took place in the spring of 1865. Rittenhouse and Peter Larew were traveling together along the Old York Road outside of Lambertville when they heard the “screams and cries” of a young girl. They found her being molested by a man from Somerset County and were able to rescue her. They brought her to her home and then found her father, a Mr. Goodfellow, to inform him what happened. We know this from testimony at the trial of the perpetrator given by this same Mr. Goodfellow. Rittenhouse himself was apparently not called to testify.17 The man, Isaac G. Wykoff, was found guilty, but his punishment was odd; he was given into the custody of the Constable who was instructed to take him to the Flemington High School and hand him over to the principal, John L. Jones, who happened to also be the Sheriff. What the sheriff was to do with him was not specified in the report of the trial.

I cannot say exactly who this Peter Larew was. He may have been the Peter M. Larew who signed up as a private in the Union Army in 1861 and was also on the list of draftees in 1864. As for “Mr. Goodfellow,” one possibility is Preston B. Goodfellow, a Lambertville carpenter. He and his wife Emma LaRoche had an daughter Jennie who was 12 years old in the 1870 census.

Rachel Hoffman died on May 20, 1862 and was buried in the Sand Brook Cemetery.18 Three years later, John P. Rittenhouse decided to give up farming. On August 21st, he sold the 68-acre farm where he had been living.19 It was located 2.5 miles from Flemington, and was probably the farm that he and his wife had been living on since they married.

Part of this property (20.27 acres) had belonged to Susan Rittenhouse’s mother Rachel, until Rachel bequeathed it to Susan in her will. The recital in John Rittenhouse’s deed explained that the farm had come to Rachel Hoffman from her father John Hoffman, jointly with her brother Levi Hoffman, and that on April 2, 1840, Levi Hoffman and wife conveyed their share in the 20+ acres to Rachel Hoffman. The Rittenhouse deed conveyed the entire 68 acres to Rachel Olmstead for $6,000, consisting of the Hoffman lot plus three more lots previously acquired by John P. Rittenhouse.20

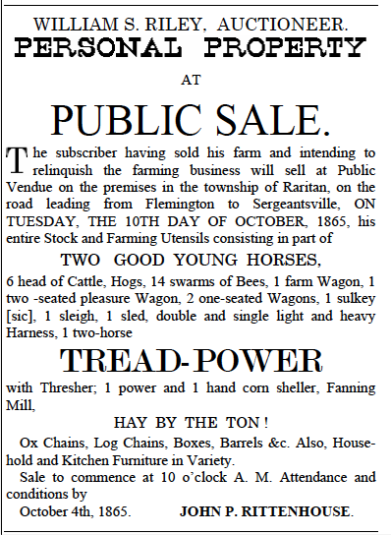

It became clear that Rittenhouse was getting out of farming altogether when he inserted an ad in the Hunterdon Gazette on October 4, 1865, announcing the sale of his entire stock of animals and farming equipment at a public auction. (This copy of the ad is the way it appears in the abstracts of the Hunterdon Gazette published by William Hartman. It is not the original ad.)

Despite taking that step, Rittenhouse still kept up his obligations with the peach growers. On November 9th he gave a “Notice to Peach Growers” that he would be “at the house of G. F. Crater, in Flemington on Tuesday, the 15th inst. At Sergeant’s Hotel, Reaville, Thursday, the 16th─ At Sergeantsville, Saturday, the 18th, to settle with those who shipped peaches by the peach train, and with whom I have not settled through their merchants in New York. Please meet me and bring your bills. J. P. Rittenhouse.”

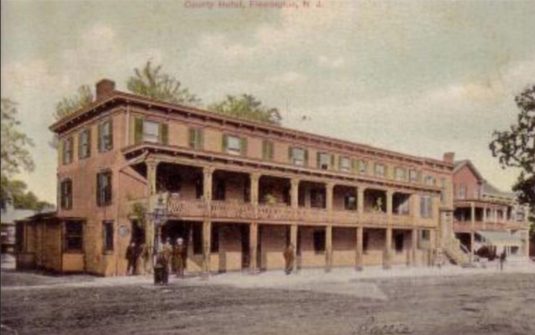

It appears that Rittenhouse had his mind on a new line of work. On March 16, 1866, the Republican reported that on April 1st, Rittenhouse would be purchasing the County House (a Flemington hotel on Main Street) from Robert Thatcher, in partnership with Elisha H. Hoagland. They were to pay a whopping $21,500. The partnership with Elisha H. Hoagland is a little odd in that Hoagland was only 23 at the time, hardly up to a challenge like this, and certainly not very well funded. In fact, the deed of sale identified Rittenhouse’s partner as John S. Hockenbury. There were two mortgages on the property, one of them given by John S. Hockenbury to John Hockenbury for $3,000.

It seems to have been expected that the owner of the County Hotel would take on the duties of poundkeeper for Raritan Township. The previous owner of the hotel, Robert Thatcher, had done so, and in 1866, Rittenhouse was elected as poundkeeper in his place. Thatcher may have sold the hotel because he was too busy being a freeholder, having been elected from Raritan Township in April 1865.21

As things turned out, Rittenhouse’s ownership of the hotel only lasted about a year. On April 3, 1867, John and Susan Rittenhouse sold the hotel back to Robert Thatcher for $17,500, a significant loss.22 The two mortgages were still outstanding. On May 24, 1867 the Republican published this very interesting story:

Almost Poisoned. On Tuesday last [May 21, 1867] John P. Rittenhouse of Flemington came near dying. He had recently relinquished hotel keeping, and had a quantity of liquor which he wished to dispose of. One day he took a person to test the liquor, with a view to purchase. He offered a drink to his companion, who politely told him to taste it first, which he did. He immediately discovered that it was “bed bug Poison”. A physician was immediately summoned, who succeeded in relieving Mr. Rittenhouse of the deadly poison before any serious consequences resulted.

After relinquishing the hotel, Rittenhouse tried something different. In November 1868, newly elected sheriff Richard Bellis appointed him Deputy Sheriff.23 This led to an interesting conflict with his old friend, Sen. Edmund Perry, because Perry had run into financial difficulties involving him in litigation resulting in his property being seized by the court. This meant that the sheriff and his deputy, John P. Rittenhouse, were obliged to take possession of the property and offer it for public sale. The first of Perry’s properties to be sacrificed was the pair of farms on the Locktown-Flemington Road. Perry had been attempting to sell them ever since he purchased them, but they were not very desirable properties, and it took many years before Perry was able to hand them off.

There is much more to the life of John P. Rittenhouse and his family, as well as to the trials and tribulations of Edmund Perry. I will save the rest of the story for another time.24

Footnotes:

- The second child was named Samuel and seems to have died young, like his older brother Elisha. The location of Elisha’s grave is not known. Samuel may well be the Samuel Rittenhouse who was buried in the Pine Hill Cemetery where the Sergeant family is buried. But there are no dates on the gravestone. Note also that Samuel Rittenhouse’s first wife, Martha Smith, who died in 1804 at the age of 36, does not have a gravestone in either the Pine Hill Cemetery or the Sandy Ridge Cemetery. However, she was most likely buried at Pine Hill. ↩

- A copy of the clipping from the Democrat was enclosed with the Isaac Rittenhouse Family Bible, on file at the Hunterdon Co. Historical Society. ↩

- Capt. Elisha E. Holcombe died February 27, 1900 and was buried in the Mt. Airy Cemetery. John Quick, who was married to Frances Holcombe, died on March 14, 1900, and was buried at the Pleasant Ridge Cemetery. Jacob Fisher was probably Jacob James Fisher who died on July 21, 1900. Clearly these three men did not die in the same week, and could not have had funerals all in the same week. Was John P. Rittenhouse exaggerating? ↩

- John Hoffman is mentioned in my article on Buchanan’s Tavern. ↩

- Hunterdon Co. Deed 113-290. ↩

- Hunterdon Gazette, 10/22/1856. ↩

- Hunterdon Gazette, March 11, 1857. The company was founded in 1856, and is still in business today as “Farmers’ Insurance Co. of Flemington.” (It even has a website.) Andrew B. Rittenhouse, not a direct relation, was named Secretary of its first annual meeting on Jan. 27, 1857, and was named one of its surveyors, covering the Locktown area. ↩

- H. C. Deed 113-290. I have never been able to link Sarah Kugler up with the rest of the Hunterdon Kugler family, or to determine if she was formerly married or a spinster. She was counted in the census records as a Delaware Township resident from 1840 through 1870. In 1850 she was listed as 60 years of age; in 1870 as 57; and in 1870 as 79 years old. ↩

- Hunterdon Gazette 3/10/1858; a shorter version appeared in the Hunterdon Republican. ↩

- H. C. Deed 120-515. ↩

- I have been unable to identify the Rittenhouse family that Smith D. Rittenhouse was associated with. ↩

- There was a John Rittenhouse listed as private in 1863 in John P. Kuhl’s seminal work on Hunterdon in the Civil War, but it was someone else. ↩

- The tax assessments can be found on Ancestry.com. Too bad the record keepers were not consistent about their information. I would have liked to have seen what Rittenhouse’s occupation was during all the war years. ↩

- Gazette, 7/1/1862. ↩

- Gazette 9/3/1862. ↩

- Gazette 3/16/1864. ↩

- Gazette, 4/19/1865. ↩

- Death date from the Isaac Rittenhouse Bible at the Hunterdon Co. Historical Society; burial from Find-a-Grave. ↩

- Hunterdon Republican, 8/25/1865. ↩

- H. C. Deed 133-060. ↩

- Gazette, April 12, 1865. ↩

- H. C. Deed 135-007. ↩

- Hunterdon Republican, 11/12/1868. ↩

- Given his history, it would seem as if there must be a photographic portrait of John P. Rittenhouse, but so far I have not found one. Perhaps someday one will turn up. ↩