The Mill in Sand Brook

Original version published in “The Bridge,” Fall 2002

This article precedes the next episode in my series on the route of the Delaware Flemington Railroad, a rail line that was surveyed, but never built. It was planned to run right through the village of Sand Brook, very close to the old mill.

I have written about Sand Brook before, especially in the article, “The Kitchen Cemetery,” and many years ago wrote an article on Kitchen’s mill for an early township newsletter. Before describing the properties in Sand Brook and to the northeast, it seems appropriate to bring the Kitchen Mill article up to date, beginning with Henry Kitchen in 1739 and ending with George Rea, Esq. in 1838. Owners who followed Rea will be described in the next article on the rail line through Sand Brook.

The village of Sand Brook came into existence as early as 1739 when Henry Kitchen decided to build a sawmill on a branch of the Neshanic known as Sand Run. The place soon became known as Kitchen’s Mill. According to James Snell and Egbert T. Bush, the mill, and subsequently the village, was located four miles southwest of Flemington, five and a half miles from Stockton, one mile from Headquarters, and two and a half miles from Sergeantsville.

The Kitchen Family

Henry Kitchen and his brothers James and Thomas are thought to have been born in Salem, Massachusetts in the 1690s, and moved to Hunterdon County as early as the 1720s. (See The Kitchen Family Tree.)

Henry’s brother James Kitchen (1679-1761) married Elizabeth Furman (1695 – 1776), daughter of Richard Furman and Sarah Way of Hopewell Township, and bought land near what became Sergeantsville, probably from Samuel Green.

Henry’s brother Thomas Kitchen (c.1690-1764) married Sarah Lambert (c.1690 -c.1770), daughter of John Lambert & Rebeckah Clowes of Burlington County. Their daughter Ann Kitchen (c.1725-after 1761) married Vincent Robins, member of the early Robins family of Amwell.

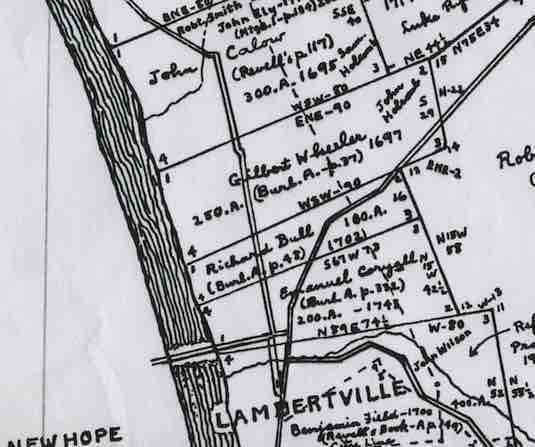

Henry Kitchen married Ann Wheeler, daughter of Gilbert and Martha Wheeler. Gilbert Wheeler was one of the early owners of proprietary tracts in Hunterdon County, although he appears to have lived first in Burlington County, then in Bucks County.

In 1726, Henry Kitchin [sic] of Amwell and wife Ann, “one of the daughters of Gilbert Wheeler, late of Bucks Co, PA, yeoman, dec’d,” sold their share in land that Ann Wheeler had acquired from her father in Makefield, Bucks County to John Clarke. Witnesses of the deed were Samuel and Sarah Green, also of Amwell.1

Henry Kitchen owned land in several parts of Amwell Township and a large tract of land on Pohatcong Creek in then Sussex (now Warren) County, but his mill property on a branch of the Neshanic was probably where he lived. Samuel and Wheeler, his two oldest sons, probably helped their father run the mill, but things came to a halt when Henry Kitchen died at the age of 55, sometime between June 25, 1745 when he wrote his will, and August 12, 1745, when the will was recorded.

Henry Kitchen left an annuity to his wife Ann, to be paid by eldest sons Samuel and Wheeler. He divided his land at Pohatcong between sons Samuel, Wheeler and Joseph, his land in “the Great Swamp” (i.e. the Croton plateau) between Samuel and Joseph, and an “old plantation in Amwell bought of Samuel Green” to son Richard. The sawmill property was divided between son Samuel and son Henry.2

Samuel Kitchen, miller of Amwell

I have not found a deed for a sale or quit claim from Henry Kitchen, Jr. to Samuel Kitchen, but other records make it clear that Samuel Kitchen, the eldest son, took over ownership and operation of the mill and built a commodious stone house nearby.

Sometime before Henry Kitchen died, son Samuel Kitchen married a woman named Mary, whose family I have not identified. The couple had nine children, from 1742 to about 1757. It seems likely that Samuel Kitchen either enlarged his parents’ house or built a new one to accommodate his large family.

In 1748 and 1751, Samuel Kitchen bought properties from Charles & Mary Hoff and from John & Mary Porter. These properties were located across from the old Buchanan’s Tavern (before Buchanans owned it) and had been owned by Daniel Robins, Sr. until his death in 1737. Kitchen sold them both to Daniel Robins’ grandson Daniel in 1760, giving Robins a mortgage of £300, which was still unpaid at the time of Robins’ death. In 1764 the property, “situated at the Foot of Robin’s Hill,” was offered for public sale.

A Scandal Divides Neighbors

In 1759, Samuel Kitchen joined with his neighbor Richard Rounsavell and several others in Amwell, Kingwood and Readington to petition for an Anglican church and minister to be established in their area. The NJ Convention in Perth Amboy responded by sending as minister one Rev. Andrew Morton who helped to establish St. Andrews Church near Ringoes.

Rev. Morton’s opinion of his congregants was not of the highest. In reporting to the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, he explained why he had not married more couples. According to Morton, the practice of being married by local magistrates had become well-established, and such ceremonies were performed

. . . in a few words, as they are tyd to no set form, but speak what happens to come into their Heads first; & to this they generally add something humourous (not to say indecent), which pleases a rough unpolished people.3

No wonder people preferred the magistrates (who were probably justices of the peace). I suspect Rev. Morton took a far more solemn and pretentious approach to the ceremony.

The congregation, such as it was, was not prosperous enough to afford a parsonage property at first, so the minister was put up in the home of John Garrison, one of the parishioners who was among those signing the petition of 1759. Garrison happened to have a daughter, Esther Garrison, who soon became pregnant. According to her, Rev. Morton was the father. This raised quite a scandal, as one can imagine. Morton’s defense to the accusation was that

“a cruel & wicked combination & conspiracy form’d first out of selfish Views & with a Design to draw me into a Marriage with a vile prostitute, & now prosecuted with all the Rancour of Malice that Disappointment & Revenge can fill the Hearts of wicked people with, has destroyed my Usefulness in my Mission for the present . . .”

Calling Garrison’s daughter “a vile prostitute” was not a good way to mollify him. Garrison was furious over the way Morton had responded and changed the locks on his house so that Morton could no longer live there. But the congregation was divided over the matter, so Garrison also put locks on the church itself, forcing those of the congregation who supported Morton to meet in the woods.

In 1762, these supporters signed a “Testimonial” to Rev. Morton’s good character. Among the 70 signers were Richard Rounsavell, Charles and Elizabeth Woolverton, Lydia Robins, Samuel Fleming, Dennis Woolverton (Warden of St. Thomas’ Church in Kingwood), and Elenor Grandin. One person who did not sign the testimonial was Samuel Kitchen.

Rounsavell was concerned about what might happen next, so he took the church books to his home and hid them there. The dispute must have cast a chill over relations between the neighbors Kitchen and Rounsavell.

Morton managed to hang on until 1766 when he departed for North Carolina, leaving Esther Garrison in the lurch. John Garrison and most of his family departed for Staten Island but his daughter Mary did not because she had married Joseph Kitchen, Samuel Kitchen’s brother.4

Running the Mill

Following this controversy, Samuel Kitchen also seemed inclined to depart. An ad appeared in the Pennsylvania Gazette on January 23, 1766 that almost certainly pertains to Kitchen’s mill.5

TO BE SOLD, A Valuable Plantation, situate in Amwell, in the County of Hunterdon, and Province of West Jersey, containing 85 Acres of Land, adjoining the Lands of Nicholas Signe, Asher Morgan, and the Road leading to Howell’s Ferry, on which is a good Stone Dwelling-house, well finished, a good Barn, and two overshot Grist-mills, one Pair of Stones in each Mill, two Boulting Mills that go by Water, one other Boulting Mill for the Country, that goes by Hand; also a Saw-mill on the same Dam, which is supplied with constant Water from living Springs, about 10 Acres of watered Meadow, which produces the best of English Hay, a good young Orchard that produces Plenty of the best Fruit, with a Number of Peach, Cherry and Pear Trees; also a Cooper’s Shop. The above Buildings are almost new, and in good Repair, and are near the Center of one of the best Townships in the Province for raising Wheat. Whoever inclines to purchase, may have easy Terms of Payment by applying to Samuel Ketchim living on the Premises, or Samuel Tucker, Esq. in Trenton.

“Ketchim” was probably a misspelling of Kitchen. The location of the house is right, and that of the milling operation impressive in its detail. Also impressive is the extent of the farming operations there and the fact that a cooper’s shop was part of the property. The fact that the buildings mentioned were “almost new” dates construction to the mid-18th century, although there must have been some buildings remaining from Henry Kitchen’s time there in the 1740s. But it is clear that Samuel Kitchen considerably enlarged his father’s operation. I suspect that Tucker was involved because Samuel Kitchen had gone into debt, perhaps mortgaging the property to him.6

It is clear there were no buyers for the Sand Brook mill property, so Kitchen seems to have decided to expand his milling operation by adding a fulling mill to the complex.7 We know this from an ad he placed in “The New York Gazette, or The Weekly Post Boy” dated April 29, 1771,8 which read:

“Wanted immediately, A Sober Man that understands tending a Fulling-Mill and dressing cloth in all the Branches of that Business, may be employed on good Terms, in Amwell, Hunterdon County, West New Jersey, by applying to the Subscriber, at said Mill. Samuel Kitchen.”

On November 15th, Kitchen advertised again,9 this time in the Pennsylvania Gazette:

“Wanted Immediately. A Fuller that can dye and dress cloth in all the branches of that business, may have good encouragement by the year, month, or to work in shares, or have the mills rented to him. There is always plenty of work. Apply to Samuel Kitchen at said mills.”

Kitchen probably advertised for a fuller because his health was failing. He wrote his will on October 29, 1771, leaving lands and mills to his wife Mary while she was a widow. After her death or remarriage, the property was to be sold along with moveable estate, and the proceeds divided among their nine children. He named as executors his wife Mary and his son-in-law John Rockafellar (1742-1832), husband of Samuel and Mary’s daughter Margaret (1742 – bef. 1799). John was a son of the first Rockafellar immigrant, Johann Pieter Rockafeller (generally known as Peter Rockafellar). He had a brother named Henry (1747-1841) who lived in Alexandria Township and was married to Margaret Kitchen’s sister Anna Kitchen. (See The Rockafellar Tree.)

Samuel Kitchen died about January, 1773, about the same age as his father when he died. In February 1775, Mary Kitchen, widow of Samuel, advertised a fulling mill to let, it being located in “a good part of the county for that business.”

1775 Feb 22, “TO BE LETT, For a year, or certain term of years, a fulling mill, with all the utensils thereunto belonging, situate in Amwell township, Hunterdon county, about four miles from Flemingtown and five from John Ringoe’s; being a good part of the county for that business, and may be entered on the first day of May next. For further particulars, enquire of the subscriber. MARY KITCHEN10

I have not found a record of how the mill was used during the Revolution, but it was probably run by Mary’s son-in-law John Rockafellar until her death in 1805.

The Will of Mary Kitchen, 1799

Mary Kitchen wrote her will on October 4, 1799. She ordered her executors (son-in-law Joshua Mott and friend Henry Trimmer) to sell her property and divide the proceeds among her children whom she named: Henry Kitchen, William Kitchen, Anna Rockafellar, Mary Mott, Elizabeth Gardner and Sarah Eike.11

The will was witnessed by Daniel Thatcher, Catherine Thatcher and Paul Kuhl. Mary must have died in early April of 1805 because on April 16th of that year, her inventory was taken by neighbors Amos Sutton and William Sine. The will was proved on May 7, 1805.

The will of Samuel Kitchen stipulated that his lands could not be sold until after his wife’s death. Therefore, on March 7, 1806, his surviving executor John Rockafellar sold the mill lot of 86 and a quarter acres and 38 perches to his son Henry Rockafellar for $3,733.33. The lot was specifically identified as the mill lot, bordering the road from Flemington to Howell’s ferry (Stockton), a small run of water (the Sand Brook), land of John Trimmer, Simon Myers, William Sine, and heirs of John Rake. Then on March 21st, Henry Rockafellow, Jr. and wife Susanna sold the property back to John Rockafellow for the same amount, $3,733.33.12

John Rockafellar and Margaret Kitchen

John Rockafellar (1742-1832) was the third son of Johann Pieter Rockafellar and Margaret Peters. He and Margaret Kitchen (1742-bef. 1799) married in 1767. They had nine children, from 1769 to about 1788. (See the Rockafellar Tree.)

In his will, dated March 22, 1787, the 76-year-old John Peter Rockafellar, Sr. made provisions for each of his sons. To son John, who by this time had a family of nine to support, he left a farm of 132 acres “where he lives” bordered by Frances Besson, Henry Dilts and Christopher Lawbacher. This farm was located on the north side of Locktown Flemington Road, less than a mile east of Locktown. Even though his father died in 1787, son John was already paying taxes on the property in 1780. All of the children of John and Margaret Kitchen Rockafellar were born there, and Margaret Kitchen Rockafellar died there, at age 56.

Although most of his children were by this time young adults, John Rockafellar soon remarried. His second wife was Catharine Larew (1768-after 1850), daughter of Moses Larew and Urania/Lavinia Thatcher, who lived on Reading Road in present-day Delaware Township.

While still in possession of the Locktown farm, John Rockafellar was also engaged in running the Kitchen mill in Sand Brook after Samuel Kitchen died in 1771. As mentioned above, after Mary Rockafellar’s death in 1805, Rockafellar took over the property. An indication of this change is the fact that in 1806, Rockafellar sold the Locktown farm of 132 acres and 11 perches to William Lair for £750 in gold or silver.13

An interesting deed dated March 1, 1805 shows that the Widow Kitchen was still in possession of the mill property at that time. It was the sale of a part of the real estate of Honis Sine, dec’d to George Holcombe.14 Honis Sine had sons William and John. William Sine acquired a large tract on the north side of Britton Road, adjacent to the Kitchen property on the west. His brother John inherited another tract of 100 acres that extended south from William Sine’s land, from Britton Road south past Yard Road. (See The Sine Farm.)The deed explicitly identified “Widow Kitchen’s land” at the northwest corner of this tract, which is where Kitchen’s mill was located. Another deed of William Sine’s, dated May 1, 181215 shows that John Rockafellar, bordering Sine’s land, was then in possession of the mills.

A mill property is generally not the sort of place where one lives out one’s later years. When Rockafellar was in his early 70s, he and wife Catharine sold the mill for $69.56/acre or $6,000.16 This was a very good price for the time.

The sale date was July 22, 1815, not long after the War of 1812 had ended, and the purchaser was George Rea, Esq. of Flemington. The property consisted of 86.5 acres and 38 perches of land and was “commonly known as the Mill Lot” in Sand Brook.17 It was located on the road from Flemington to Howell’s Ferry, i.e., Route 523. The mill was situated on today’s Britton Road, but in 1815 that was not a public road, and the property extended west to Route 523. It was bordered by John Trimmer, Simon Myers, William Sine, and land of John Rake dec’d, all long-time residents of the Sand Brook neighborhood.

After selling the mill lot, John and Catharine went to live on a farm of 64.75 acres bordering John Besson and John Higgins, which they had purchased from John and Margaret Besson Hughes just a couple months before selling the mill lot.18 That property was located back up in the swamp, on the Raritan Township side of Route 579, some distance east of the old farm on the Locktown Flemington Road.

John Rockafellar wrote his will on July 1, 1828, naming son-in-law George Fauss and “my friend Samuel Fauss” his executors. George Fauss was the son of Samuel Fauss & Mary Moore, who owned the farm on Sand Brook Headquarters Road described in Route Not Taken, part five. After Samuel Fauss died on April 1, 1831, Rockafellar named James J. Fisher to replace him as executor.

After John Rockafellar died on December 19, 1832, at the remarkable age of 90, his much younger wife Catharine went to live with daughter Delilah Fauss (1805-1891) and husband George Fauss (1804-1877). She was counted with George & Delilah Fauss in the 1850 Delaware Township census as age 83. She probably died not long afterwards, but I have not found a date or located where she was buried.

George Rea, Esq.

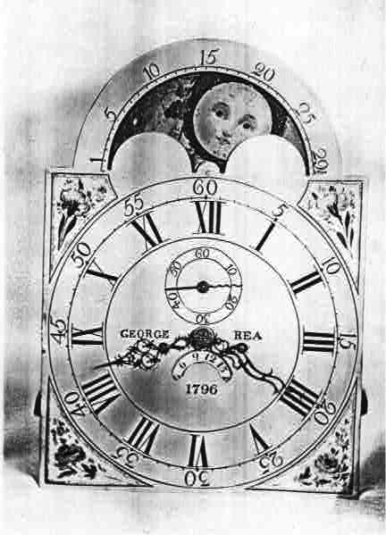

Let us return to the Kitchen Mill and its new owner in 1815, George Rea, Esq. of Flemington (1774-1838). He was the eldest son of George Rea and Ann Clover of Pittstown. He began his career as a clock & watchmaker, moving from place to place—Princeton, Trenton, and finally Flemington, where he set up shop on Main Street.19 About 1801, George Rea married Elizabeth Runkle (1782-1868), daughter of Abraham Runkle and Sarah Stout. The couple had eight children, two of whom died as infants.

Rea’s clocks were very popular, but there is only one clock-face left that has been identified as his. It is quite lovely and is owned by the Hunterdon County Historical Society.

While living in Flemington, Rea served as its first Postmaster from 1808 to 1813, as judge on the Court of Common Pleas in 1808, and as Justice from 1812 to 1818.

His father, George Rea, Sr. of Pittstown, wrote his will on May 5, 1813, leaving financial bequests to his wife Ann, sons Samuel, Alexander and John, and daughters Mary Hixon and Elizabeth Taylor. He ordered that his real estate be sold and proceeds divided between his children. But he made no mention of his son George, who was about 38 by this time, and apparently not at all dependent on his father.20 He was not involved in executing the will either.

However, shortly after his father’s death, Rea decided to retire from clock making and try something else, i.e., milling and farming. Hence his purchase of the Sand Brook mill lot in 1815. But it was not until 1818 that he retired from the bench.

1815 was quite a year of transition. In March, April and May, George and Elizabeth Rea, as residents of Flemington, sold tracts of land to William Maxwell, Albert Kinney and George Cronce. I can’t help but wonder if they were raising funds for the purpose of buying the mill property. As mentioned above, Rea paid a whopping $6,000 for it.

Repairing & upgrading the Mill

Curiously, a week before signing the deed for the Mill lot with John & Catharine Rockafellar, George Rea bought from his prospective neighbor, William Sine

“all the land necessary for carrying or conveying a race from the water Grist mill now erecting or repairing by the said George Rea on his land in Amwell, being on a stream of water commonly known by the name of Rake’s or Sand Brook, so that the sd George Rea may have full power and authority at all times to open the said race or channel through the Farm now belonging to me sufficiently wide to carry off the water from his said Mill, and to Repair and keep the same in order forever.”21

The expenses of repairing the old mill must have been more than Rea anticipated. On May 30, 1817, he divided off a lot of 27.5 acres from the mill lot and sold it to George Ege for $1,105.25.22 This was the southwest corner of the original mill property that was bordered by Route 523 on the west and the Sand Brook Road on the south. It later became used as a poorhouse, and in the 1970s was owned by Assemblywoman Barbara McConnell.

Here is a photo of the house taken in the early 20th century:

Since Rea was quite well-to-do when he moved to Sand Brook, it seems most likely that he made improvements to the old Kitchen house as well as the mill. Clearly someone enlarged it significantly.

In addition to running the mill, Rea also farmed his property and sold horses. This ad appeared in the Hunterdon Gazette on April 5, 1826:

The beautiful full-blooded HORSE HAMLET, Lately purchased by me from George Rea, Esq. of Flemington, will stand this season at my stable, in the township of Hopewell, three miles below Pennington, on the Middle Road to Trenton. . . . For further account of Hamlet’s pedigree, and the rates of service, see handed-bills. Edmund Burroughs.

Despite several deeds to and from George Rea in the years 1817 through 1825, it is not possible to say for sure whether Rea was actually living at Sand Brook or if he kept his house in Flemington, because in all his deeds he was identified as “of Amwell,” which includes both Sand Brook and Flemington. The advertisement above in 1826 is one exception, stating that Rea was “of Flemington.”23

Selling the Mill Lot

On January 16, 1828, when he was 44 years old, George Rea advertised his gristmill for sale in the Hunterdon Gazette:

FARM and MILLS, FOR PRIVATE SALE

The subscriber offers at Private Sale, that valuable Farm and Mills, and Distillery, situate in the township of Amwell, near the road leading from Flemington to Center Bridge. The farm contains about 70 acres of land, a good proportion of which is woodland, and about 12 acres of bottom meadow. On the farm is a grist mill, nearly new, with two pair of burr stones, in good order, and is a good flour mill. The Distillery is new. This property is now in the tenure of Charles Wolverton, who will show the premises to those who may wish to view them. Terms of payment will be accommodating. – For further particulars, apply to the subscriber, in Flemington. George Rea.

It is curious that the property included a distillery. This is the only mention I have found of one being part of the complex. Also, I know no reason why Rea should sell the mill in 1828. The only significant fact is that 1828 was the year that John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson ran against each other for President. As there was no interest shown in 1828, Rea tried again on January 13, 1830:

Valuable Mill Property

FOR SALE.Will be exposed to sale at PUBLIC VENDUE, On Monday the 8th of February next, on the premises, (if not previously disposed of,) That valuable Grist Mill, on the Sandbrook, 4 miles from Flemington, in the township of Amwell, now occupied by Charles Wolverton. The Mill is in good repair, having one pair of burrs, and a good pair of country stones, and a tolerable supply of water. There are attached to the Mill 60 acres of land, 12 of which is meadow; on which is a stone dwelling house sufficiently large to accommodate two families; a frame barn, and bearing apple orchard. ALSO, at the same time, a Lot of clear land, containing one acre and three-fourths, on the road between the Sandbrook and Buchanan’s tavern. Payments made easy, and the title good. Sale to commence at 12 o’clock. Conditions made known by George Rea.24

Who was the Charles Wolverton who was operating the Sand Brook mill in 1830? I cannot say. But it is clear now that Rea was no longer in residence.

Unfortunately, once again, Rea did not get a buyer. So, he busied himself inventing a new machine for preparing flax “for manufacturing.” He advertised in the Gazette on August 31, 1831 that he was ready to buy “any quantity of Merchantable flax, rotted or unrotted.” He also noted that he was about to take out a patent on this new machine and would then sell the rights to use it. Clearly, George Rea was an enterprising person. He was still pursuing this occupation in 1836 when he put this ad in the Gazette on September 13, 1836.

WANTED: 3000 BUSHELS OF FLAXSEED, At my Mills, in Amwell. I will pay the highest price in Cash – And keep all sorts of Meal & Feed. [signed] George Rea.

George Rea in Court

1831 was an interesting year for another reason. George Rea and his neighbor Philip Rake, son of John Rake, got into a dispute that ended up in court. Court papers are not clear about the nature of the complaint, but it concerned the flow of water from the Sand Brook. On Dec. 9, 1831, William Sine, by then about 78 years old, testified that he had known the mill property in Sandbrook since 1775 and lived on land adjoining it from then until the present.25 He said that the Sand Brook ran through the mill property and the property of Philip Rake the defendant; that about forty years ago [in 1790] John Rockafellar dug a ditch to water the meadow and built a dam close to the line fence to turn the water into the meadow. The meadow was benefitted by the water and doubled in value. Sine also said that George Rea built a dam about two rods below that, but that the water could not have been got into the ditch without backwattering onto Rake’s property.26

When cross-examined by the defendant’s lawyer, Sine said he did not know if the present course of the stream is the same that it always was; that there was a pond there before it was cleared off, the spring dried up and good crops raised; also that the present dam was put up to keep the water from overflowing.

Apparently, this was one of those cases that never seems to end. A year later, on June 23, 1832, John Rockafellar, “being ancient and infirm” (he later stated that he was 90 years old) gave his own deposition in the Rea v. Rake case. He said he had known the mill property for 60 years or more (which takes him back to about the time that Samuel Kitchen died), that he was the owner for much of that time and that he was also familiar with the Sand Brook and that the race to the mill was built before his memory.

He (Rockafellar) built the little dam about 40 years ago, to turn the water on the meadow. It was 200 yards or more below the dam that turned the water to the mill, just below the line between George Rea and John Rake. At that time there was nothing to divert the natural channel from its course except his little dam and the dam to turn the water to the mill. The meadow was 10 or 12 acres and the water ran over nearly the whole of it. Rockafellar said that the only other source of water to the meadow was a small stream coming out of the old fulling mill dam. He said that John Rake did not interfere with his little dam for it was not on his land. Rockafellar was unable to sign his name to this testimony, perhaps due to his advanced age.

Oddly enough, the court record does not show the outcome of the case. Most likely it was settled by the litigants.27

Seven years after the court proceeding, George Rea, Esq. died on June 27, 1838, age 64. He was buried in the Baptist Cemetery in Flemington. Much to my surprise, I could not find an obituary for him.28

Note: After publishing the article it was called to my attention that the photograph of the George Rea house was mistaken for the house located on the lot sold to George Ege. So I added a photograph of the Ege house to help clarify the matter. The photograph came from the Kurzenberger collection.

The next article will deal with Rea’s estate and the mill’s new owner, Hiram Moore. The rail line was designed to run between Moore’s property and that of George N. Holcombe, owner of William Sine’s old farm. It then proceeded northeast through the old Sutton farm on its way to Flemington.

Footnotes:

- Deed abstracted in June D. Brown, “Abstracts of Bucks County Pennsylvania Land Records, 1711-1749, Heritage Books, 1998, pp. 153-154. ↩

- I do not have a copy of the will itself. This information comes from the abstract published in NJ Archives, Abstracts of Wills. In the abstract, the will does not mention who got the other half of the sawmill. However, Dennis Bertland, in his narrative for the National Register application for Sand Brook, stated that Samuel’s brother Henry was given the other half. ↩

- History of East Amwell, p. 200. I confess, this was such a great story that I could not resist including it. ↩

- Some sources claim that Mary Garrison married Samuel Kitchen rather than Joseph. It is true that Samuel’s wife was named Mary, but he did not have a son named John, which is crucial, because in 1774, John Garrison of Staten Island wrote his will (NY Wills vol. 29, 1772-1775) leaving a bequest to his grandson John Kitchen. He did not name John’s parents, but in fact, Joseph Kitchen did have a son John and Samuel Kitchen did not. Joseph and Mary Garrison Kitchen left Hunterdon County for Berkeley, Virginia sometime in the 1760s. ↩

- NJA News Extracts, vol. 6, 1766-1767 p. 15. ↩

- I have one hesitation about attributing this to Samuel Kitchen of Sand Brook. In the Pennsylvania Gazette, just three months later (NJA News Extracts, vol. 6, p. 66), a notice was published in the March 27th edition informing readers that the Hunterdon County Court of Common Pleas would hear from the creditors of Samuel Ketcham of Hopewell (my emphasis) on April 8th, to show why ”the Petition of the sd Samuel Ketcham, and the major Part in Value of his Creditors shall not be complied with, and he discharged according to Law.” ↩

- A fulling mill is designed to “full” cloth. The word “full” in this sense comes from the Middle English, when it meant to trample under foot. After wool has been woven into cloth, it needs to be pounded to allow the web to tighten and firm up. After fulling, cloth shrinks by about a quarter to a half of its size. Fulling mills came into existence about the late 12th or early 13th century, but in Europe it was common for the fulling to be done by the pounding of feet. Fulling mills replaced the feet with large hammers, and were built in the Colonies as early as the 1640’s. ↩

- NJA News Extracts, vol. 8, p. 454. ↩

- NJA News Extracts, vol. 8, p. 646. ↩

- from The Pennsylvania Journal No 1681; NJA News Extracts, First Series, Vol 31, p. 70. ↩

- She also named granddaughter Catherine Kitchen. I cannot name Catharine’s parents because both of Mary Kitchen’s sons Henry and William moved to Canada, and I have no further information on them. ↩

- H.C. Deeds Book 12 p. 488, Book 13 p. 46. Notice the various spellings of Rockafeller, Rockafellar and Rockafellow. ↩

- H.C. Deed Book 14, p. 332. ↩

- H.C. Deed Book 11 p. 43. ↩

- H.C. Deed 031-186. ↩

- H. C. Deed Book 24 p.530. ↩

- A “perch” is an ancient measurement of land. An acre is equivalent to four roods, and a rood contains 40 perches. A perch is 25 square meters. ↩

- H.C. Deed Book 24 p. 178. ↩

- See James P. Snell, History of Hunterdon County, p. 341, and David A. Sperling, “History of Clockmaking in Flemington, Hunterdon County, NJ., 1790-1840,” published in Main Antique Digest, 2012. ↩

- I wanted to recheck that will in the Abstracts of Wills, NJ Archives series, but I do not own the last volume, 1814-1817, and thanks to the quarantine, I will not be visiting the Library or Historical Society any time soon. ↩

- H.C. Deed Book 24 p. 368. ↩

- H.C. Deed Book 28 p.114. ↩

- Another exception was the deed of October 10, 1825 when Rea, again “of Flemington” purchased from William Bishop water rights for land “now in the tenure of Samuel Holcombe.” (H.C. Deed Book 39 p. 398.) I have not located this property, but I do know it was not in Sand Brook. It appears that Rea owned another mill property closer to Flemington, but I have not studied the deeds to get the exact location. ↩

- Note: A search for George Rea’s name in the Hunterdon Gazette of 1830 shows that he was still actively performing his duties as at the Orphans Court and as a Justice, performing marriages. ↩

- Rea’s property was on Block 26 lot 25; Sine’s was on what was once known as lot 24 until it was absorbed into lot 2. ↩

- Hunterdon Co. Court of Appeals, #129. ↩

- I have not been able to clearly locate the “line between George Rea and John Rake because the deeds have courses that were not carefully measured, and frankly make no sense. Kitchen’s Meadow was located on the south side of Britton Road. ↩

- None was published in the Hunterdon Gazette. The Hunterdon Democrat did not start publishing until September 1838, so there was nothing for him there. Even more baffling, I found nothing for him in the Trenton papers either. It’s almost as if his family decided not to submit an obit for publication. ↩

Stuart James Smith

April 4, 2020 @ 8:07 am

Thanks for this informative and interesting article. My Uncle Alex Oceanak and Aunt Rosie lived in the bungalow opposite the stone house in Sandbrook before 1959, and remember playing with the boy who lived there. There was also a greek revival store that sold milk and bread and we were given change to buy pink and white hostess snowball cakes, that always made me feel sick afterwards. I knew Kitchens and Rockafellars from Holland Twp and went to school with them. The clockmaker Rea was unknown to me growing up in Pittstown and do wonder where his father’s house would have been. I also spent much time on the Reaville Rd. visiting friends when young , and remember farmers my father knew named Polhemus, which I lately have found in my genealogy. Thanks for stirring up my memories.

Karen Zielinski

April 4, 2020 @ 9:06 am

Thank you for this history of Sandbrook’s mills. I would love to see old maps of the village.

Randy Fonner

April 4, 2020 @ 8:29 pm

Thank you – nice article.