The surprising history behind a modest building

My last article was the first of the series I hope to write about Flemington’s 19th century buildings with arches on their rooflines. That last article featured the Clock Tower building at the corner of Main Street and Bloomfield Avenue, built in 1874 by George A. Rea. Now let’s stroll south along Main Street to visit the next building in this series.

At the south corner of the Main & Bloomfield intersection, there stands a large building that once was headquarters for the Flemington National Bank, and next to that comes the Higgins News Agency. Believe it or not, that is the next building on my list.

At the south corner of the Main & Bloomfield intersection, there stands a large building that once was headquarters for the Flemington National Bank, and next to that comes the Higgins News Agency. Believe it or not, that is the next building on my list.

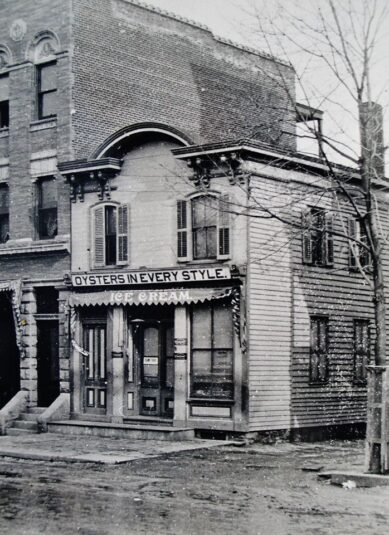

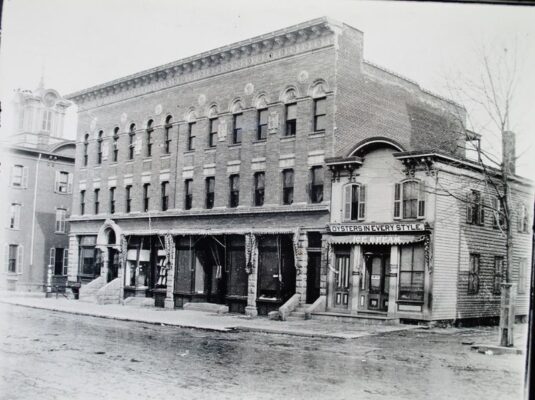

Like so many other 19th century buildings, this one has changed a lot from its original appearance. In this case, the changes have kept this 19th century building from inclusion in the survey of historical buildings by the Hunterdon Cultural & Heritage Commission. If it had kept its original appearance it would look like the photograph below, which is how it looked around 1900.1

The Oyster Craze

The Oyster Craze

As you can see, it once was an oyster restaurant. Oysters were incredibly popular in the 19th century. They were the equivalent of today’s fast food. Back then oysters were much larger and far more abundant than they are today. One writer noted that they were “as large as a lady’s hand,” and another wrote that eating an American oyster was like eating a baby.

Oysters cannot be found growing in Hunterdon County. They need the kind of conditions found in the shallow salt waters along the east coast, especially from New York City to Maryland. Oysters had been harvested there by native Americans long before the European immigrants learned to enjoy them.

In 1829, meetings were being held to promote the idea of a canal to link the Delaware River with the Raritan River which empties into Raritan Bay south of Staten Island. One such meeting was held at the Flemington Courthouse on July 28, 1829, at which Nathaniel Saxton was chairman. Several resolutions were agreed on, along with a list of New Jersey’s advantages which would be enhanced by the canal. This included “the great extent and value of the oyster grounds lying along the coasts and in the bays and rivers within the jurisdiction of the state.” There is some irony in the fact that the canal enabled increased transportation and industry in the Raritan River which gradually decimated the oyster beds.

Another problem was overharvesting, which people became aware of as early as the 18th century. State Legislatures in New York and New Jersey reacted by passing laws that prohibited oystering by non-residents.2 This meant that New Jersey residents consumed New Jersey oysters.

Oyster season was generally limited to eight months of the year, all months with an R in their names, September through April,3 so when the season began, Hunterdon newspapers featured ads by restaurant owners and merchants boasting that Amboy Oysters were available. Those were New Jersey oysters from the beds along the coast near Perth Amboy. (For those unfamiliar with NJ geography, Perth Amboy is located at the mouth of the Raritan River, directly west of the southern tip of Staten Island, and due east from Flemington.)

But my articles are meant to focus on the builders and owners of those distinctive buildings with arches in their rooflines. So, the question is, who built the oyster restaurant and when? I regret to say I have not been able to identify the builder of the first structure on the site, but it is clear that a building of some kind was there in 1848.

The Buchanans of Perth Amboy

On November 22, 1848, this notice appeared in the Hunterdon Gazette:

AMBOY OYSTERS! The subscribers having fitted up an OYSTER SALOON in the building next to Hart’s Hotel [my emphasis], would respectfully announce to the Public that they have just received a fresh supply of Amboy Oysters, which they will be pleased to serve up in every style, to all who may favor them with their patronage. Having been engaged in the above business for a long time, they flatter themselves that they are able to compete with, if not to surpass, any other establishment in the “diggins,” as far as cheapness and goodness are concerned. Families and Parties supplied at the shortest notice, on reasonable terms. [signed] ANTHONY BUCHANON, JAMES BUCHANON.

“The building next to Hart’s Hotel,” i.e., today’s Union Hotel, could be either on the north or south side, but since I never came across any reference to the building on the south (described in my article “A Store A Bank, A Mansion”) as a restaurant, and the one on the north, today’s Higgins News Agency, always was a restaurant, I’m going to assume that the Buchanans were selling their oysters there.

The editor of the Hunterdon Gazette was a devoted customer, as we can tell from this notice on February 7, 1849:

OYSTERS THAT ARE OYSTERS! To those who may be attending Court next week, and to all others who are fond of Oysters, either in the shell or cooked, we would say call on the Messrs. Buchanon, next door to Hart’s Hotel, and try some of their large and elegant AMBOY OYSTERS. They are far superior to anything of the kind ever before kept in Flemington. They are too delicious to talk about!

“Too delicious to talk about?” That is saying a lot for a newspaper editor.

James Buchanan and Anthony Buchanan were bona fide oystermen, who lived in Perth Amboy where the oysters were harvested. They were identified as oystermen in the census records of 1850, with Anthony living in South Amboy with wife Sarah and four children, and James living in Perth Amboy with a wife also named Sarah, and their four children.

I thought perhaps these Buchanans might be related to the Buchanan family of Amwell/Delaware Township, which I wrote about in “Buchanan’s, A Tavern With a Long History.” (The Buchanan Family Tree does not include James and Anthony.) My supposition was increased when I learned that James Buchanan of Perth Amboy married an Amwell girl in 1839. She was Sarah Ann Elgordon, eldest child of Philip Elgordon and Elizabeth Carr. Philip and Elizabeth married on Sept 3, 1808, which is one of the only solid dates I have. Presumably Sarah was born not long afterwards.

Philip died young (before 1827) leaving his widow to raise five children. When Sarah Ann was about 25, she married James Buchanan of Perth Amboy. How this couple met is something of a mystery. The wedding took place on October 2, 1839, and was announced in the Hunterdon Democrat of Oct. 15, 1839, and the Hunterdon Gazette of Oct. 22, 1839, with James identified as “of Perth Amboy” and Sarah Ann living “near Sergeantsville.” The couple made their home in Perth Amboy and were counted there for the 1850 census. In 1860 they were living in Shrewsbury, Monmouth County, but James was still a fisherman.

The Buchanans did not own the building where they sold oysters. In 1849 it was taken over by one James Clark who advertised in the Gazette on March 14th:

AMBOY OYSTERS! The subscriber having fitted up an OYSTER SALOON in the building next to Hart’s Hotel, [my emphasis] would respectfully announce to the Public that he has constantly on hand a supply of Amboy Oysters, which he will be pleased to serve up in every style, to all who may favor him with their patronage. Having been engaged in the above business for a long time, he flatters himself that he is able to compete with, if not to surpass, any other establishment in the “diggins,” as far as cheapness and goodness are concerned. Families and Parties supplied at the shortest notice, on reasonable terms. Flemington, James Clark.

Note the subtle reference to “diggins,” a term that had been used by the Buchanan’s in their advertisement. One gets the feeling that Clark and the Buchanans did not get along. More evidence of this is found in a notice in the Gazette for Sept. 19, 1849, in which Buchanan announced that he had opened an “oyster saloon” in the basement of the hotel owned by Adam C. Davis, which was located across the street from Clark’s restaurant. Buchanan was offering oysters for retail and in quantity, as he announced in the same ad:

Persons who intend keeping Oysters for retail, would do well to get their supplies of him, as he will accommodate them on reasonable terms. Families supplied at the shortest notice.

As for retail, Buchanan announced that his oysters were prepared in all sorts of styles, “either fried, stewed, roasted, opened or in the shell.”

“Oysters In Every Style”

Because oysters can survive for days after being taken out of the water, restaurants were always able to offer raw oysters to their customers. (The French preferred them that way.) But people quickly figured out how cook oysters in just about every way imaginable.

I was struck by the sign on the building’s awning that proclaimed, “Oysters In Every Style.” At first, I thought that was something original, but in fact, the phrase “oysters in every style” showed up everywhere, including the New York oyster saloons in the 1840s that Charles Dickens wrote about in his American Notes. One historian wrote:

Across the map, nineteenth-century America was mad for oysters. Found on the East and West coasts, oysters became the stuff of mass and class dining, available from both street vendors and the fanciest of restaurants. They were eaten raw or cooked by various methods, including frying, grilling, roasting, and stewing. Pickled oysters were also a thing. . .4

Not only did Americans like their oysters in every possible variation, they also devoured them in very large quantities; raw was just the beginning. This craze for oysters explains why there was a time when every restaurant on Flemington’s Main Street was offering oysters in every style on their menus.

Meanwhile, James Clark had found someone to run his oyster restaurant: he was John T. Hewitt, who advertised on Nov. 10, 1852:

OYSTERS—The Subscriber would inform the public that he has constantly on hand at his establishment next door to the Union Hotel, a large supply of superior Amboy Oysters, which he is prepared to serve up in the most approved style. He would also say to families, that he can furnish them with Oysters either by the quart or hundred, on liberal terms. JOHN HEWITT.5

That same month, James Buchanan advertised that he would “visit Flemington every Friday, during the season, with the best of Amboy Oysters, with which he will be happy to supply all who wish them, on reasonable terms.” So, it seems Buchanan did not continue to run an oyster restaurant in the Davis hotel.

As mentioned above, James & Sarah Buchanan moved from Perth Amboy to Shrewsbury between 1850 and 1860. This change may have been triggered by the death of Anthony Buchanan in 1857, when he was only 32 years old. Then in 1869, the Buchanans retired to a 60-acre farm in Delaware Township that was conveyed that year to Sarah Buchanan by commissioners to sell the real estate that her father Philip Elgordon possessed when he died.6 From 1870 on until his death in 1896, James Buchanan was a farmer—no longer an oysterman.7

Hugh & Matilda Capner

I had mentioned the fact that Buchanan and Clark did not own the property where they sold oysters. It was in fact acquired on April 1, 1848 by Hugh Capner for $1,000 from John G. Reading and wife Sarah, just seven months before James Buchanan’s first advertisement.8 The property description was for a lot “with the office thereon erected” in the Village of Flemington, bordering Main Street and the Blackwell property, which was the building adjacent to the restaurant on the north. The deed specified that “it is agreed by the parties that the alley or open space between the said office and the Tavern House now occupied by Mahlon C. Hart is forever hereafter to be kept open for the mutual accommodation of sd Hart and sd Hugh Capner.”

John G. Reading was none other than the owner of the store I wrote about previously, later known as the Fulper store, located on the south side of the Union Hotel. (See “A Store, A Bank, A Mansion.” I will not go further back in time for now, because it is my hope in the future to publish an article about the 18th century history of Flemington property owners.)

On May 6, 1848, Capner purchased an extra strip of land along the restaurant lot from Bartles, Bonnell & Higgins (Charles & Eliza Bartles, Alex. V. & Catherine Bonnell, and Judiah & Charity Higgins) for $150.9 The Capners kept this property for 17 years, leasing the restaurant to various men. As we have seen from the above advertisement, in 1852, that tenant was:

John T. Hewitt

John T. Hewitt had much in common with James Buchanan. He was an oysterman from Perth Amboy who sold oysters in Flemington for a few years, then retired to a Hunterdon farm. He advertised on Nov. 10, 1852, that he “has constantly on hand at his establishment next door to the Union Hotel, a large supply of superior Amboy Oysters, which he is prepared to serve up in the most approved style.”

In 1855, he was selling oysters “wholesale and retail . . . at his old stand, first door north of the Union Hotel.” And was still at it in 1858 when the Hunterdon Gazette moved into the same building:

“MOVED. The Office of the HUNTERDON GAZETTE will hereafter be found in the building one door North of Crater’s Hotel, in the large room formerly occupied by Peter C. Schenck, in the rear of Lawyer Van Fleet’s Office, and immediately above the Restaurant of John T. Hewitt. Esq. [my emphasis] Enter left hand door, keep straight ahead, pass through another door, and you will certainly find us. We may add, ready to receive money for subscriptions, advertising, jobbing, &c., &c.10

But on Nov. 30, 1859, the Gazette announced that Mr. Hewitt had retired.

OYSTERS! OYSTERS!! The well-known Oyster Stand of John T. Hewitt, Esq., next door to the Hotel of Geo. F. Crater in this place, has recently changed Proprietors; Mr. Hewitt having sold out to our friend Peter Larue, formerly of Copper Hill, who will hereafter serve up the luscious bivalves to suit the tastes of the many visitors who nightly resort to this favorite Restaurant. Peter not only designs keeping Oysters, but Refreshments generally. We bespeak for him a fair share of public patronage. The improvements he proposes making in and about the establishment, will add to the enjoyment and comfort of his customers. Call and see him.

Like his predecessors, John T. Hewitt retired to farming on his Raritan Township property, and later moved to Rahway where he was a wood dealer, until his death in 1891.

As for Peter Larue, he did not last long, for in April 1860, the Gazette stated that Reading Moore had “commenced business on Monday in the Restaurant in the basement of the building we in part occupy.” The restaurant was a constant, but the managers were not, for only six months later, it was being run by a “Mr. Garron,” about whom I know nothing at all.

John L. Van Fleet

This high turnover came to an end in 1862. On April 2, 1862, the Hunterdon Gazette ran this notice:

OYSTERS. The Restaurant in the basement of this building, is now kept by John L. Van Fleet, the popular epicurean of Flemington. He proposes soon to fit it up in good style and have things pleasant and comfortable for visitors.

John L. Van Fleet (1826-1873) was the son of Aaron VanFleet and Ann Lowe of Readington Township (hence the initial L.). Aaron VanFleet died in 1849, only 45 years old. At first, his only son John took over the farm; the 1850 census put him with his birth family in Readington Township. But almost immediately after that he was buying property in Flemington. In 1853, he and Jacob S. Smith bought a property on Mine Street from Charles Bartles, which they soon sold to others.11

Two years later, Jacob Suydam Smith purchased the County House Hotel, almost directly across Main Street Flemington from the George A. Rea building. This is interesting because Jacob S. Smith’s brother was Nathaniel Green Smith (1814-1888) who ran a bakery across from the hotel and who married Eleanor Bellis (1811-1885) in 1835. N. G. & Eleanor Smith had a daughter Phebe, who married John L. Van Fleet on December 17, 1856. (See The Clock Tower Building for more on N. G. Smith.)

In 1860, John L. Van Fleet was living with Phebe’s parents, working as a wagon painter, according to the census of that year. But he quickly shifted to his preferred occupation, running a restaurant. And in no time, he became known as a “popular epicurean.” In October 1863, the Gazette observed that

Mr. John Van Fleet has opened a room over his Saloon, in the basement of the Gazette building, where he intends to serve oysters, cooked in any style desired. This arrangement is for the accommodation of females who may desire a roast, a fry or a stew, in privacy, without the interruption of a crowd. Ladies may call in this upper saloon, if they desire, without fear of intrusion, and we would just say, John knows how to serve up the bivalves.

The Ladies’ Entrance

By “interruption of a crowd,” the editors were observing in the politest way that the boys in the oyster saloon, enjoying beers with their oysters, could get a bit rowdy. On Nov. 4, 1863, the Gazette’s editor took note of Van Fleet’s ladies’ saloon:

THOSE BIVALVES. Last week we told you that John Van Fleet, the great Oyster monger, who stews, fries and roasts, every night, e’en to the small wee hours of the morning, has fitted up accommodations where ladies may be served with oysters free from intrusion. A right snug place is this saloon, and we think it an improvement which should be well patronized by all who like to indulge in the luxuries of shellfish.

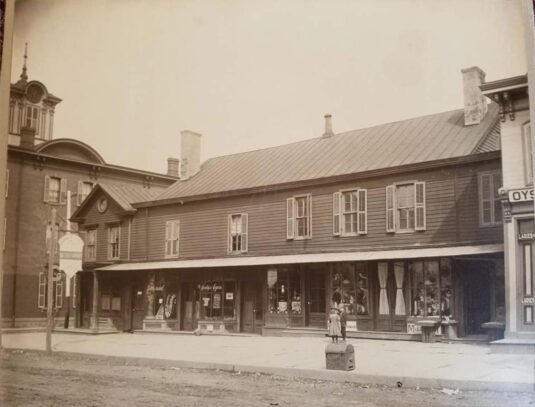

Here is a photograph of the building that preceded the bank building, known as Blackwell’s Row. Take a close look at the far right of the picture; there you will see the oyster restaurant with its left-hand door labeled “Ladies Entrance.” This was a feature that store owners liked to brag about in their newspaper ads. There were two reasons why special rooms were required. The principal one was that it was common practice to provide large amounts of alcohol along with the oysters. In New York City, where oyster cellars abounded, they were typically called oyster saloons or oyster & lager beer saloons. The second reason is that during these years, unescorted females were automatically assumed to be prostitutes, which prompted some fairly loud and insulting behavior from inebriated males.

Here is a photograph of the building that preceded the bank building, known as Blackwell’s Row. Take a close look at the far right of the picture; there you will see the oyster restaurant with its left-hand door labeled “Ladies Entrance.” This was a feature that store owners liked to brag about in their newspaper ads. There were two reasons why special rooms were required. The principal one was that it was common practice to provide large amounts of alcohol along with the oysters. In New York City, where oyster cellars abounded, they were typically called oyster saloons or oyster & lager beer saloons. The second reason is that during these years, unescorted females were automatically assumed to be prostitutes, which prompted some fairly loud and insulting behavior from inebriated males.

One of Van Fleet’s competitors, Hiram G. Voorhees, who ran an oyster restaurant near the train station, advertised on June 7, 1865 that “Mr. V. will always have a full supply of Ice Cream, which will be served to ladies in an apartment fitted up for the purpose, and free from observation.” The Ladies’ Saloon may have been private, but that did not mean free from thievery, as seen in this notice of Feb. 3, 1864:

RETURN THE PROPERTY. The person who entered the Ladies Saloon in John Van Fleet’s Oyster Establishment and took therefrom a silver-plated Castor, will receive the thanks of the owner by returning the same. If it is not forthcoming immediately, the parties will be set down as thieves, and proceedings instituted against them forthwith.

1865, A New Owner

It seems that John Van Fleet had leased his restaurant from Hugh and Matilda Capner ever since 1862. That changed on April 1, 1865 when the Capners sold the property to Phebe Ann Van Fleet for $3,000.12 The property was described as bordering Main Street, the lot once owned by John T. Blackwell and “the Tavern House now occupied by Geo. F. Crater.” One wonders why the lot wasn’t sold to John Van Fleet, and to that I have no answer. It is an interesting example of properties being sold to the female in a married couple.

This was a pattern in Phebe’s family, as her mother, Eleanor Bellis Smith, purchased four lots in Flemington from Miller and Mary Kline in 1878. It was also a pattern with this restaurant, when Anna T. Lovell, wife of Fred Lovell, bought the restaurant property in 1913.

Meanwhile, John Van Fleet carried on. In December 1865, he announced that he was offering “a choice dish of Terripin” [i.e., terrapin, or turtles] in addition to “Oysters in every style.”

1866, Big Changes

The end of the Civil War brought many changes to people’s lives. It certainly brought change to the Hunterdon Gazette, which was taken over by Charles Tomlinson. Tomlinson wanted to buy the Hunterdon Democrat, but its owner wasn’t selling, so he bought the Gazette instead and changed the paper’s name to “The Democrat.” Meanwhile, Adam Bellis, editor of the Hunterdon Democrat, failed to keep up with the new competition. On July 3, 1867, both papers disappeared and were replaced by “The Hunterdon County Democrat.13

For the time being, the new paper occupied the quarters of the old Hunterdon Gazette, on the second floor of the oyster restaurant, which explains this notice from the last editor of the Hunterdon Gazette and first editor of the new Hunterdon County Democrat, J. Rhutsen Schenk, on July 18, 1866:

REMOVED. Van Fleet & Moore have removed their Oyster and Dining Rooms, from the basement of The Democrat building, to that of the new Masonic Hall. These gentlemen have now as complete a place for catering to the public, as any other in the State, and our citizens will give them a full patronage, for they well deserve it. We do not know of anyone who is so well qualified to keep a saloon as John Van Fleet, and Moore is as clever a man as can be found. Ladies! you who want ice-cream, just step into the ladies’ department. It is delightfully cool; but the cream is cooler; it is furnished tastefully, and at all times free from noise or confusion.14

The Masonic Hall

John Van Fleet was among the many who were impressed by the new bank building, constructed by John C. Hopewell and named by him Masonic Hall. (See “Flemington’s First Bank”.) It was open for business in April 1866, and by July of that year, Van Fleet had moved in. In August 1866, the Hunterdon Republican also took notice:

John L. Van Fleet & Co. announces his Restaurant in the basement of Masonic Hall, Flemington. They have one of the largest and most complete saloons to be found in the State of New Jersey, and respectfully invites all their friends, and the public to give them a call. OYSTERS in very style, served up at all hours. The best quality of Lager, Ale, Porter, etc.

It is rather curious that John Van Fleet moved his restaurant out of the building that his wife Phoebe still owned. Here’s another curiosity: the highly opinionated and controversial editor of the old Hunterdon Democrat was Adam Bellis, who happened to be the uncle of Phebe Smith Van Fleet. And yet, for many years, the Democrat’s competitor, the Gazette, was Phebe’s tenant. That must have made for interesting conversations. Then when Charles Tomlinson took over both newspapers, Van Fleet moved out. No doubt there is a story there.

A Four-Year Interval, 1866 – 1870

It is clear at this point that I have relied to a great extent on the Hunterdon Gazette for information about the oyster restaurant. What I have actually relied on are the abstracts of the Gazette made by William Hartman and his volunteers. There are no such abstracts for the newspaper that replaced it, the Hunterdon County Democrat, something I constantly regret. The Hunterdon Republican was in print during this time and was also abstracted by Hartman, but it had little to say about Van Fleet. It reported frequently on John C. Hopewell’s activities but said nothing about his tenants.

This means that for the years 1866 to 1870, I have no good information on what John Van Fleet was doing. Presumably he carried on the restaurant business in the Masonic Hall during most of that four-year period. But in 1870, he changed location again. The reason remains obscure, but I would not be surprised to learn that the Democrat had moved out.

On March 17, 1870, the Republican ran this announcement:

Renovations. The building next to Crater’s Hotel, is undergoing extensive alterations and repairs. John L. Van Fleet, who owns the property will occupy it with his restaurant and billiard saloon and will fit it up in first-class style.

As we have seen, the building actually belonged to Van Fleet’s wife Phebe. The renovations almost certainly involved the new façade with the arch in the roofline.

The following June when the 1870 census was taken, Van Fleet was 43 years old, keeping a restaurant and living with wife Phebe, age 34, and mother Ann Van Fleet, age 70. Phebe’s parents, Nathaniel Green and Ellen Smith, were living in Crater’s Hotel. Van Fleet’s property was valued at $6,000, another hint that the renovations had involved the new façade.

What Van Fleet ended up with had a strong resemblance to another building on Main Street, one that was occupied by the Hunterdon County Democrat—a two-story building with an arch in its front roofline, nearly identical to Van Fleet’s Restaurant. But that building was not constructed until 1875. Since Van Fleet made his improvements in 1870, we must conclude that the Democrat’s building was patterned after the oyster restaurant instead of the other way around.

What Van Fleet ended up with had a strong resemblance to another building on Main Street, one that was occupied by the Hunterdon County Democrat—a two-story building with an arch in its front roofline, nearly identical to Van Fleet’s Restaurant. But that building was not constructed until 1875. Since Van Fleet made his improvements in 1870, we must conclude that the Democrat’s building was patterned after the oyster restaurant instead of the other way around.

As far as I can tell, 1870 is the earliest date for a building with the arch in its front roofline among those similar buildings along Main Street.

1873, More Changes

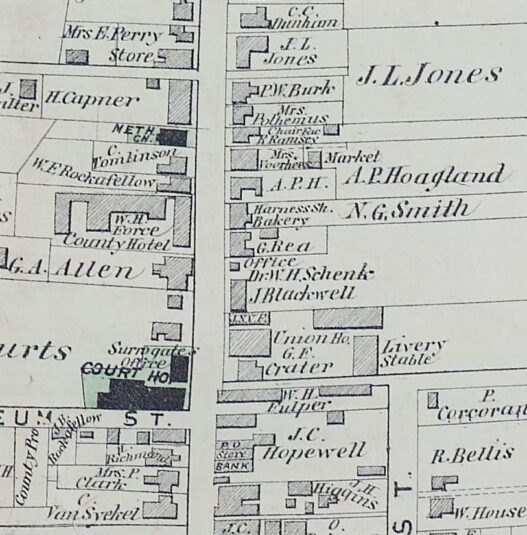

The Beers-Comstock Atlas of Hunterdon County was published in 1873 and included a detail of Flemington showing the merchants of Main Street.

The Beers-Comstock Atlas of Hunterdon County was published in 1873 and included a detail of Flemington showing the merchants of Main Street.

The oyster restaurant was located between “J. Blackwell,” or Blackwell’s Row, and “Union Ho.,” or Union Hotel. “JNVF” stood for John N. Van Fleet, which was a mistake, since his name was John L. Van Fleet, not John N.

Regrettably, the Atlas does not state what month it was published, but it must have been sometime before June 10th, for on that date John L. Van Fleet died at the age of 46. The obituary in the Hunterdon Republican (published June 12th) stated that this came “after a long illness,” a fate that was all too common for men in the 19th century. What the illness was is a mystery, but the Democrat noted that it was “a protracted and very painful illness.” If that was the case, then it is all the more remarkable that he could have maintained such a busy and successful restaurant for as long as he did.15

Phoebe’s Tenants

Again, I find an interval without information, which is the four years between the death of John Van Fleet in 1873 and 1877, when Phebe Van Fleet married Lewis F. Reinert.

Lewis Reinert (1856-1929, sometimes spelled Louis) was the son of German immigrants, George Reinert and Catherine Hartman, who were living in New Hope, PA in 1870 with their eight children, including ‘Louis’ age 14. George was a confectioner, and his son became a baker. It is my very strong suspicion that Lewis got a job working for Phebe’s father, Nathaniel G. Smith, who ran a bakery a couple doors north of George A. Rea’s building on Main Street. That would explain how Lewis and Phoebe became acquainted.

In 1878, Phoebe found new tenants for her restaurant, as advertised in the Hunterdon Republican for April 25, 1878:

The Union Restaurant and Billiard Hall, next door to the Hotel of Lambert Humphrey in Flemington, has changed hands and the new proprietors would respectfully announce to their many friends that they have remodeled and tastefully fitted it up and are now prepared to furnish Oysters in every style, wholesale and retail, ice cream and water ices, etc. By John P. Rittenhouse & Farley S. Taylor.

Note that by this time, the Union Hotel that had been run for many years by George F. Crater, was now in the hands of Lambert Humphrey.

I have written about John P. Rittenhouse before (“John P. Rittenhouse” who was elected sheriff from 1871 to 1874). His partnership with Farley S. Taylor was short-lived, as this notice in the Republican shows, published Nov 21, 1878:

Dissolution. The partnership heretofore existing between John P. Rittenhouse and Farley S. Taylor has this day been dissolved and the business will be carried on at The Union Restaurant and Billiard Hall, next door to the Union Hotel by John P. Rittenhouse and Jehiel Hassel.

Jehiel Hassel had previously partnered with John H. Stockton to run the oyster restaurant located in Masonic Hall. Hassel sold his interest to Stockton in June 1878. I cannot say what happened to him after partnering with John P. Rittenhouse, but this partnership must have followed the pattern and dissolved after a short period of time. In the 1880 census, John P. Rittenhouse was described as a lumber merchant. Also that year, Lewis Reinert was listed as a 26-year-old baker living with wife Phoebe, age 43. Next to them were listed N.G. Smith 66 baker and wife Ellen 68, and next to them was George A. Rea, age 55, merchant.

Even though Phoebe still owned the restaurant, Lewis now claimed it as his own, as seen in this notice in the Hunterdon Republican of August 8, 1881:

Lost on Thursday last, either in my saloon or on the street, sixty dollars in five and ten dollar bills. A fair reward will be paid for the return of the money to Lewis F. Reinert at the Union Restaurant in Flemington.

Half a year later, on January 12, 1882, Reinert announced:

Lewis F. Reinert wishes to inform his friends that he has given up the idea of leasing the Union Restaurant in Flemington and will continue to conduct the business himself.

And yet, less than a month later, on Feb. 2, 1882, this appeared:

George Mattison and Jacob Moore have leased the Union Restaurant from Lewis F. Reinert. They are both well acquainted with the business, having been employed for some time in a similar business.16

Two weeks later, on February 16th, Moore & Mattison advertised their offerings:

MOORE & MATTISON, Wholesale and Retail Dealers in Oysters, Terrapin, Cape May Clams, Ice Cream and Water Ices in Season. Picnics and parties supplied at Low Prices. Dining and Billiard Rooms Attached. Also, Ladies Room, nicely fitted up. One door north of the Union Hotel, Flemington. By Jacob Moore and George Mattison.

As with previous partnerships, this one was short-lived, dissolving by the end of the year. On Jan. 4, 1883, they gave notice:

Jacob Moore and George Mattison of the Union Restaurant, next door to Humphrey’s Hotel, have dissolved their partnership. The business will be continued by George Mattison at the same place.

Thereafter, George Mattison advertised regularly in the Republican with oysters always the primary attraction. But he quit after only five years. By 1900 he had moved to Branchburg in Somerset County, and died there in 1907, age 61.

Theodore R. Bellis

Again, the restaurant was in need of a tenant. Mattison was immediately replaced by Theodore R. Bellis. On December 30, 1885, the Republican announced that

Theodore B. Bellis has leased the Union Restaurant, next door to the Hotel of Lambert Humphrey in Flemington and he will take possession on January 1, 1886. He will continue it as a first-class restaurant and billiard room and will make every effort to merit the patronage of the public.17

Theodore Besson Bellis (1843-1912) was the son of William Cramer Bellis and Mary Eliza Smith.18 He was a member of Co. A, 15th NJ Regiment during the Civil War. Following the war, he married Anne E. Reed of Quick’s Mill in East Amwell and had a son Charles in 1868. The census for 1870 lists the family in Bridgewater, Somerset County, with Theodore working as a miller. Oddly enough, they cannot be found in the 1880 census, but in 1885, the NJ State Census lists them as Flemington residents.

Theodore Bellis was enthusiastic about his restaurant and may well have been the one responsible for the “Oysters In Every Style” awning. Here is a sample of his advertisements in the Hunterdon Republican, the first on Sept. 12, 1888, the next on May 21, 1890, and the last on October 7, 1896:

OYSTERS! OYSTERS! The Oyster season is now open at the Union Restaurant, one door north of the Union Hotel, Flemington. I am making arrangements to supply the whole county with the choicest growth of Oysters during the balance of 1888 and the “R” months of 1889. The Union Restaurant is bound to keep at the head of the procession in the quality of its Oysters. It will, as heretofore, be the Leading Oyster House in the County. We will sell in any quantity, from half a dozen on the half shell to a sack or carload. Parties, Festivals, etc., supplied at short notice and at low rates. Particular attention given to orders of this kind. Clams of the most popular brands, in their season. Also, keep on hand a fine selection of Candies, Fruits, Nuts, Tobacco & Cigars. Theodore B. Bellis, Main St., Flemington.

ICE CREAM. Although ice is high this season, I want to say to the many patrons of my Union Restaurant Ice Cream Parlors, that the Ice Cream this year manufactured by me will be of the best quality as usual. The Ladies Parlor has just been fitted up and is as neat, clean, cozy and cool as any room in the county and polite and gentlemanly treatment is assured to all its patrons. Ice Cream fashioned into tasty shapes & delivered to all parts of Flemington. Also, Oysters, Clams, & all that belongs to a First Class Eating House, will be kept as usual together with Tobacco, Cigars, Fruits, Nuts, Confectionery, &c. Don’t miss the place! One door north of the Union Hotel. By Theodore B. Bellis.

Go To The Union Restaurant, Main St., Flemington. Buy your Oysters where you can get the best. The Union Restaurant is still headquarters for the delicious bivalve. We trim them here to suit every taste and here is where you get the prime Stew, Pan, Roast or Fry. Particular attention given to family orders. Also, prepared to furnish church festivals, weddings, parties, etc. Meals at all hours. As usual, our stock of Cigars and Tobacco, Candies, Nuts, Tropical Fruits, &c., is up to high G. Remember, good Oysters cost no more than inferior ones. We have them fresh, fat and fine all through the season. None but competent caterers employed. Theodore B. Bellis.

Next Door, the Richards Building

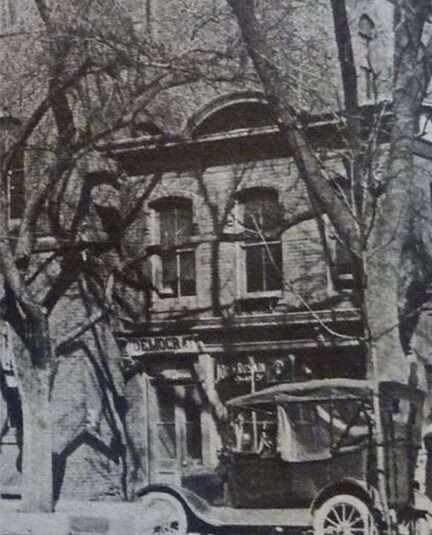

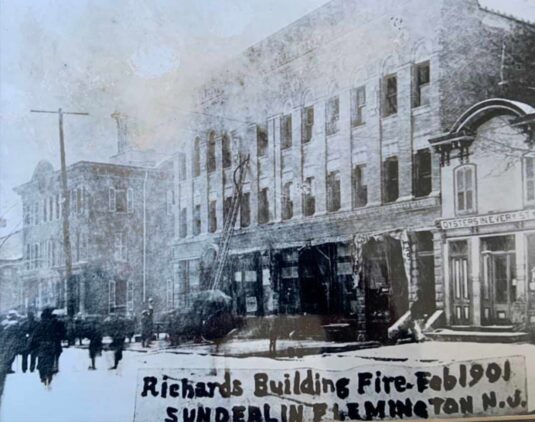

The building that replaced Blackwell’s Row (pictured right) was built by William Richards in 1897. Only four years later it caught fire, and someone was there to get a photograph.

The building that replaced Blackwell’s Row (pictured right) was built by William Richards in 1897. Only four years later it caught fire, and someone was there to get a photograph.

You can see the restaurant next door, which fortunately was not adversely affected. You can also see that in 1901 it still sported the awning proclaiming, “Oysters In Every Style.” Here’s another photograph of the bank building and the restaurant:

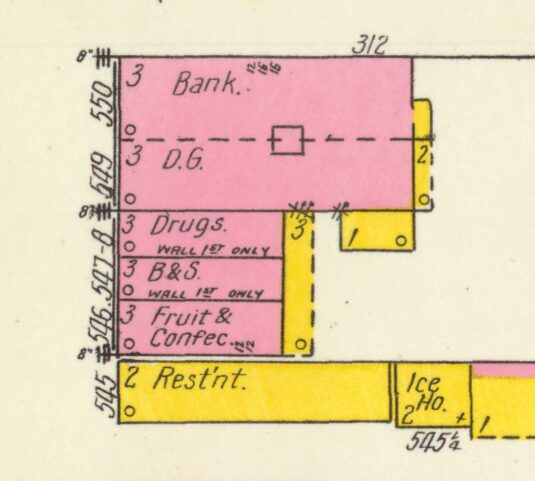

Sanborn Maps of 1902

Sanborn Maps of 1902

Given the fire in the bank building, one can see why insurance companies had become an important part of the local economy. The most well-known of these was the Sanborn Company, because the maps they made of properties are such a valuable resource for researchers. Here is the map made in 1902 of the bank building and the restaurant.

Pink designates brick buildings and yellow is for wood frame structures. Note the icehouse behind the restaurant. Patti Deluca and Richard Higgins, in a recent Facebook conversation, recalled that the building was an oyster bar with an icehouse in the back. The ice was delivered through a manhole in the front of the building and may still be there (i.e., the manhole, not the ice).19

Pink designates brick buildings and yellow is for wood frame structures. Note the icehouse behind the restaurant. Patti Deluca and Richard Higgins, in a recent Facebook conversation, recalled that the building was an oyster bar with an icehouse in the back. The ice was delivered through a manhole in the front of the building and may still be there (i.e., the manhole, not the ice).19

Betsey Driver wrote that the cold room where the oysters were stored extended under the sidewalk in front of the shop and partially under Main Street. “There is a steel cover on the chute opening that appears to be a manhole in the sidewalk where the oysters were delivered. It’s the reason the streetscape sidewalk wasn’t done in front of Higgins. The sidewalk is the roof of the cold room.”

Census records show that Theodore Bellis continued in the restaurant business up through 1910, when he was 67 years old. He died in on January 5, 1912, at the age of 68, and was buried in the Prospect Hill Cemetery. His widow Annie lived with their single daughter Elizabeth until her death at the age of 90 in 1935.

In 1885, Phoebe Smith Van Fleet and husband Lewis Reinert were counted in the NJ State Census as residents of Flemington. Soon after that, the couple moved to Philadelphia. Then on September 29, 1896, while Theodore Bellis was still running the restaurant, Phebe sold the property to Joel H. DeVictor, another resident of Philadelphia, for $4,600.20

At this point I was wondering how much further forward I could go with this. Just for the sake of curiosity, I looked up Mr. DeVictor in the deed index and found that he held on to the lot, probably enjoying the rent his tenant, Theodore Bellis, was paying, until 1912, the year that Bellis died. Then he sold it to Robert V. Corcoran.21 I have no information on Mr. Corcoran—he was not a Hunterdon personality, but pushing a little further, I learned that in 1913, Robt V. Corcoran sold the restaurant lot to Anna T. Lovell.22

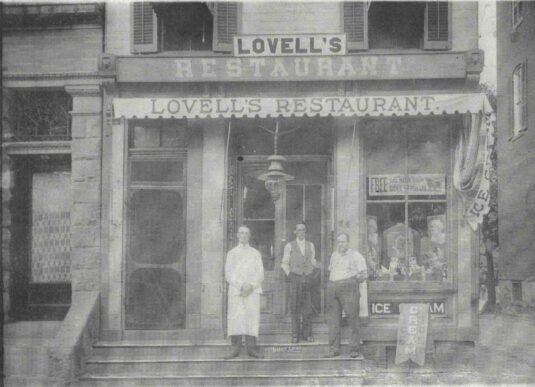

Lovell’s Restaurant

Anna’s husband, Frederick E. Lovell, took over management of the restaurant, probably around 1910, when the census of that year indicated that Fred Lovell was running a restaurant on Flemington’s Main Street.

That census suggests that Fred and Anna married about 1907. I have no information on Anna T. Lovell’s birth family. Frederick E. Lovell (c.1876- after 1930) was the son of George Lovell, who came to Hunterdon County from New York, and Mary Ellen Pedrick, daughter of Hezekiah & Mary Pedrick, also of New York, but later of Raritan Township.

Here is a photograph of what became known as Lovell’s Restaurant.

The 1930 census stated that Fred Lovell both owned and managed his restaurant and owned a house at 62 North Main Street where he lived with his uncle, Josiah Pedrick, age 67. Fred was designated as married, not widowed, but wife Anna was not in the household. And here I confess I have no further information about the Lovell family.

However, I expect that Lovell was still running his restaurant in 1935 when the Lindbergh trial took place in Flemington. This was a pretty overwhelming event for a small country town, as Charles Lindbergh and wife Anne Morrow were national figures, and the kidnapping and murder of their son commanded national attention.

Here I must end this study of the history of a very unremarkable-looking building. It certainly demonstrates the truth of the old saying that appearances can be deceiving.

Afterthought:

It is interesting that oyster restaurants were able to serve alcohol (mostly beer), even though they were not considered taverns. As the 19th century rolled along, it seems as if the distinction between taverns and restaurants got rather blurred.

Another Afterthought:

Another Afterthought:

Following publication, Dennis Bertland shared with me a photograph of the old ice house that was located behind the restaurant. I do not know if it is still there, but the picture certainly belongs with this article.

Footnotes:

- Many of the photographs illustrating this article were shared by architect, Chris Pickell. ↩

- Information about oyster harvesting and marketing comes from Mark Kurlansky, The Big Oyster; History on the Half Shell, NY: Random House, 2006. ↩

- Correction: Originally, I had this reversed, which limited the season to only four months, until a couple readers caught the mistake. One of them showed the article to a professional oyster farmer, who pointed out that “A bacteria, vibrio, blooms in warmer months that can cause a nasty stomach ache.” ↩

- Christopher Everette Cenac, with Claire Domangue Joller, Eyes of an Eagle: Jean-Pierre Cenac, Patriarch: An Illustrated History of Early Houma-Terrebonne, Univ. Press of Mississippi, 2011; Chapter 22, “The Oyster is King,” pp. 205-231. ↩

- I will be writing about the Union Hotel next, another building with arches in its roofline, and hope to discover exactly when and why the name became Union Hotel. ↩

- H.C. Deed Book 144 p.28. ↩

- In November 1880, James and Sarah sold their Delaware Twp. property to their son Nelson E. Buchanan, who lived in Neptune, Monmouth County. He and wife Althea Collins remained in Monmouth and sold the Delaware farm in 1893 to Mary Plum of Frenchtown. ↩

- H.C. Deed Book 91 p.12. ↩

- H.C. Deed Book 103 p.88. ↩

- Hunterdon Gazette, Jan 6, 1858, Suydam & Abel editors & publishers. ↩

- H.C. Deeds, Book 106 p.709; Book 107, pp. 447, 547; and Book 112 p.759. ↩

- H.C. Deed Book 131 p.565. ↩

- This is all explained by Hubert G. Schmidt in his excellent book, The Press in Hunterdon County, 1825-1925, Hunterdon County Democrat, 1961. ↩

- I have not found a reference to the full name of Van Fleet’s partner, but I suspect it was Reading Moore who had briefly run the oyster restaurant back in 1860. ↩

- Van Fleet wrote a will, which I have not seen. The Republican reported that his executor, David Van Fleet, presented an account of his estate to the Orphans Court on May 3, 1765 and April 3, 1876. As far as I know, David VanFleet, Esq. was not related to John L. VanFleet. ↩

- George Mattison (c.1846-1907) was the son of John B. Mattison and Euphemia Ann Case. (He never married.) Jacob Moore (1844-1914) was the son of William S. Moore & Susan Burroughs; he was married to Rebecca R. Brewer (1846-1895). ↩

- Keep in mind that owning the restaurant was not the same as owning the property where the restaurant was located. While Bellis became the restaurant owner, Phoebe Reinert was still the property owner. ↩

- Here is another case of families intermarrying: William Rockafellar Bellis and Mary Ellen Cramer had 12 children, one of whom was William Cramer Bellis, father of Theodore, another was Eleanor Bellis who married Nathaniel G. Smith. N. G. Smith was the brother of Wm Cramer Bellis’s wife Mary Eliza Smith. Theodore R. Bellis is also an example of people with similar or identical names being contemporaries. There was a Theodore Bellis and a Theodore R. Bellis at this time, and it can often be difficult to decide which Theodore is being referred to. ↩

- Many thanks to John Allen for directing me to the Princeton University Library website where these maps can be found, and also sharing the page explaining the color code. ↩

- H.C. Deed Book 246 p.348. ↩

- H.C. Deed Book 305 p.053. ↩

- H.C. Deed Book 308 p.174. ↩

Peter Goodell

September 4, 2021 @ 11:33 am

Early in the article you stateful oyster season was May through August; always have been under the impression that oyster season was September through April, the months with an “R”. The local taste for oysters did not disappear completely. My grandfather, my father, and now I prepare scalloped oysters for holiday celebrations. At least until recently; the main ingredient, oysters, are still abundant, the OTC crackers used in the recipe have disappeared. The Original Trenton Cracker Company was located in lambertville for many years.

Marfy Goodspeed

September 4, 2021 @ 12:38 pm

You are right that the actual oyster season was most of the year. This business of no months with an R in them was an old myth that people in the 19th century sometimes adhered to and sometimes ignored. I was mentioning because old James Buchanan made much of having Amboy Oysters in the spring, clearly something people had been waiting for.