When The Hotel Was a Tavern

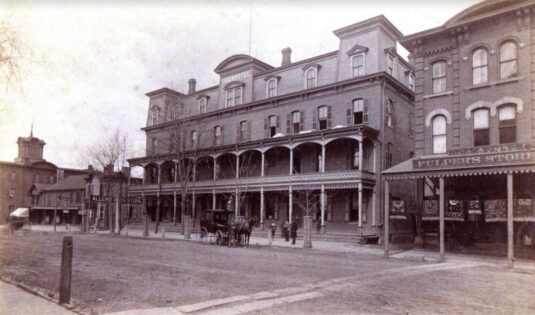

My last article concerned an old restaurant on Main Street (today’s Higgins News Agency) that long ago sported a lovely arch along its front roofline. Previous to that, was the George Rea building, that had a similar arch on all four sides. Looking for the next building on Flemington’s Main Street with that unusual feature, we come to none other than the Union Hotel.

The building as we know it today is clearly a 19th century building. In fact, my research shows that it was most likely constructed about 1877 by hotel owner Lambert Humphrey. Having discovered that, I thought I would write my history of the hotel by working backwards from Mr. Humphrey. But as a narrative, I can’t make it work. So instead, I’m going to go back to the very beginning—before Flemington even existed—and make my way forward to Mr. Humphrey.

Before the Revolution

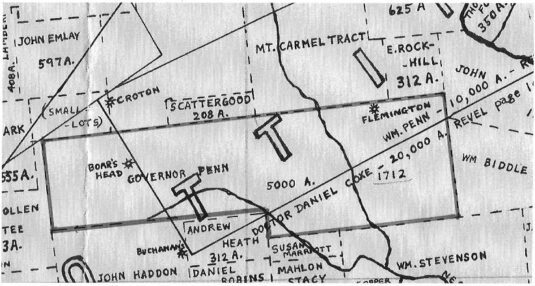

The Quakers had been living in the southern part of what was then known as West New Jersey ever since the 1680s. By 1700, they were hungry for more land and named a committee to negotiate with leaders of the Native People, i.e., the Lenape. As a result, in 1703 they acquired a massive tract of 150,000 acres. (See “John Reading and the Creation of Hunterdon County.”) Once that property was surveyed, lots began to be sold off by the West Jersey Proprietors, and in 1712, a tract of 5,000 acres was surveyed for William Penn.1

That year, Penn suffered a terrible stroke and returned to England where he spent his last years. He died in 1718 and his property was inherited by his three sons, Thomas, William, and Richard. It was not until the 1730s and 1740s that the Penn sons started selling off parcels from the 5,000 acres. In 1738, they sold 374 acres to Johann Phillip Kase, a property that we know today as the Dvoor Farm.

David Eveland

Previous to that, on May 28, 1737, they carved out from the northeast corner of the 5,000 acres, a tract of 147 acres and sold it to Johann David Eveland, an immigrant from Hessen Germany who arrived in New York as early as 1710. I learned about the sale to Eveland from the recital in a deed recorded by his executors on June 12, 1762,2 in which the Eveland property was sold to a partnership consisting of Christopher Marshall, James Eddy, William Morris, Jr., Thomas Lowrey, and Gershom Lee.

Main Street

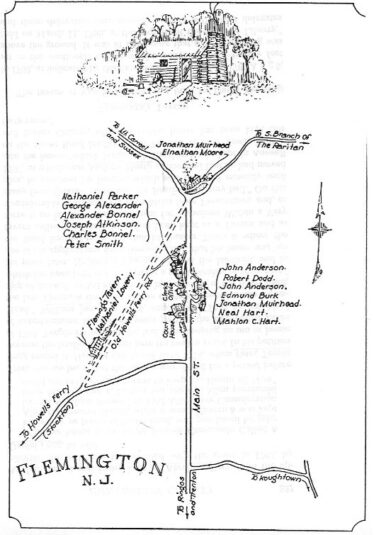

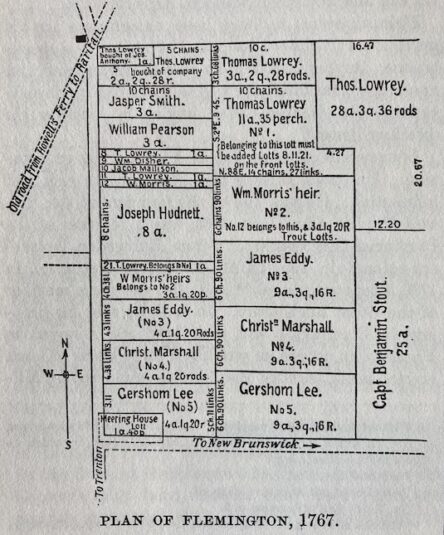

Just as the Penn brothers divided their father’s tract into smaller lots, this partnership did the same with the 147 acres. Fortunately, they drew a map of the division, which James P. Snell published in his history of Hunterdon County.3 Snell mislabeled the map as “Plan of Flemington, 1767,” when it really only shows the eastern half of the town. The western half of the town consisted of a 6.5-acre lot that in 1766 was owned by Thomas Lowrey and Gershom Lee. They did not divide it further, so no map of that period is available.

What stands out to me about this map is that it shows that the western boundary of the Eveland tract ran along what was called in old deeds “the street running through Flemington” or “the road from Flemington to Trenton,” in other words, Main Street, except it was never called Main Street. And on the south, the map shows the street from Flemington to New Brunswick, which is today’s Church Street.

The survey for David Eveland was most likely drawn to run along the existing road. The other very old road at the time (today’s Route 523) ran from Howell’s Ferry (Stockton) to the Case/Dvoor property and on in a northeasterly direction through the northern part of Flemington to the village of Raritan, as shown on Snell’s version of the 1767 map. (This explains why the Samuel Fleming house on Bonnell Street appears to be set at an angle to the current road.)

All of these 18th century roads were based on Indian trails, which followed the contours of the land. Indian trails were never perfectly straight roads—that was how European surveyors drew them. Main Street was part of an Indian trail that ran south to Trenton and north to Sussex County, today’s Route 31, in other words, “the road to Trenton.” It seems likely that Main Street as it appears on the 1767 map was the old Indian trail straightened out through Flemington by the Penn-Eveland surveyors in 1737.

The Lowrey Partnership

I suspect that Thomas Lowrey, a gentleman who knew how to prosper from real estate investments, was the guiding force behind the purchase from the Eveland heirs and the subsequent division and sale of properties in what became the eastern half of Flemington.

I can’t help but wonder if Lowrey imagined that the nascent village would turn into Hunterdon’s county seat. As many readers know, Thomas Lowrey was also a son-in-law of Samuel & Esther Fleming. Gershom Lee (c.1700-c.1774) was another early resident of Flemington. The other three partners purchasing the Eveland tract, Christopher Marshall, James Eddy and William Morris, were absentee investors who gradually sold their rights to Lowrey and Lee.

The Division Map of 1767 shows that some of the lots were set off to men who were not the original 5 partners, i.e., Jasper Smith, William Pearson, William Disher, Jacob Mattison, Joseph Hudnett and Benjamin Stout. It also shows a lot set off for what was the Baptist Meeting House, one of the earliest churches in Hunterdon. Jacob Mattison was one of its congregants.4

As you can see, there were five small lots, numbered 8 through 12, sold to Thomas Lowrey, William Disher, Jacob Mattison, another one to Lowrey and one to William Morris. They were each one acre, with short road frontage and lots of room in the back. This was fairly common in an early town like Flemington; residents needed space behind their houses for barns and other structures to accommodate their horses, cows and pigs, which were essential for 18th-century living.

Sales to these other men took place between 1762 and 1767 when the map was drawn. Lot 10 was sold to Jacob Mattison as early as 1764,5 and it was Lot 10 that became the site of the Union Hotel.

Jacob Mattison

Jacob Mattison was born on Nov. 16, 1709, to Scottish immigrants, Aaron Mattison and Elizabeth Wright, who settled in Freehold, Monmouth County. The earliest record I have of him is in 1731, when he married Anne Hankinson, also of Monmouth County. Anne (1709-1762) was the daughter of English immigrants, Thomas Hankinson and Elizabeth Manson. One year later, Anne’s brother, Joseph Hankinson (1712-1783) married Jacob Mattison’s sister Rachel Mattison (1707-1784). Probably not long afterwards, the two couples migrated from Monmouth to Hunterdon County.

Jacob and Anne Mattison had nine children before Anne died at the age of 52. Three years later, Jacob Mattison married Esther Henry (1718- ), widow of William Bishop (c.1710-1761). She was the mother of four boys; son Joseph (1746-1812) married Rachel Kline and lived in Kingwood Township. Son David who became a colonel during the Revolution, married Ann Schenck in 1775 and had six children.

Sidenote: Name Confusion

The Amwell freeholders (i.e., property owners) of 1741 were listed by Norman Wittwer in the Genealogical Magazine of NJ. Among them were Jacob and Joseph Matthewson. This was no doubt a variation on the name Mattison. Also listed was “David Eveline,” undoubtedly David Eveland. Thomas Lowrey and Gershom Lee were not listed because they were children in 1741. However, Samuel “Flemming” was there.

Another place were Jacob Mattison’s name got confused was in his will, which is referenced in deeds for his property in 1805. Searching for a will for Jacob Mattison will fail because it was recorded for John Mattison instead of Jacob. But the will names Jacob’s first wife Ann as well as his children. And the executors named in the deeds for Jacob Mattison are the same ones named in the will for John Mattison. This double name, John Jacob, is confirmed by his gravestone identifies him as John Jacob Mattison. Once I realized the mistake, things began to make sense.

The Role of Taverns in the Community

Flemington was not much of a place in 1767. And yet, in only 22 years, it became the county seat of Hunterdon County. One of the reasons this small village became so important was its strategic location at the intersection of well-traveled roads. And wherever major roads intersected, one could be sure of finding at least one tavern, often two or three.

Flemington acquired the designation of county seat through a vote taken of the citizens of the Hunterdon County in 1790, which included all of present-day Mercer. Apparently, the vote was overwhelmingly favorable for Flemington, even though the town consisted of only 10 or 12 houses.6 Things had not changed much by 1808 when, according to Snell (p.328):

From the Presbyterian church to the Baptist [i.e., from the Civil War monument to Church Street] there were but sixteen houses, of which three were occupied as taverns.

If one is curious to learn about early taverns in Hunterdon as well as the rest of West New Jersey, it is essential to consult a book by Charles S. Boyer called Old Inns & Taverns in West Jersey, published in 1958. The book sheds much light on the role of taverns in local communities—they really were essential as places for travelers to fortify themselves along their journeys, as well as public spaces where community gatherings were possible, such as Sheriff’s sales, elections and court proceedings, the sort of gatherings that were not appropriate in the local church. They were places where newspapers were available for perusal, and company was there to share opinions with.

The Mattison Tavern

Jacob Mattison purchased lot 10 of the Eveland tract in 1764. He certainly did not need that lot, as he had acquired nearly 300 acres near the Neshanic River, probably not long after moving to Hunterdon from Monmouth County in the 1730s. It seems likely that he had his son Joseph in mind when he bought Lot 10. Joseph Mattison obtained a tavern license in 1777 and was identified as a tavernkeeper in Amwell Township in the 1780 tax ratables.

Boyer’s Version

However, Charles S. Boyer did not take Jacob or Joseph Mattison into account. As you can see on the map below (p. 231), he identified John Anderson as the first tavernkeeper at the site of the Union Hotel, noting that in 1772, Anderson stated that he had taken a house for which “he payeth a heavy Rent.” But that proves nothing, as there were other taverns in Flemington besides Mattison’s. (Unfortunately, Boyers did not say where this quote came from.)

Along with John Anderson, Boyer listed the tavernkeepers at the Union Hotel site as Robert Dodd, John Anderson again, Edmund Burk, John Muirhead and Neal Hart. Well, we can agree on Neal Hart, who took over in 1808. But as for the others—I think not. Muirhead and Burk were active tavernkeepers in the 1800s but not at the Union Hotel location. Robert Dodd is a complete mystery, and Anderson is also a puzzle. There is an Anderson-Mattison connection: Jacob Mattison & Anne Hankinson had a daughter Elizabeth (1731-1809) who married about 1750 a John Anderson (1725-1772), but he lived in Lebanon Twp.

In describing the role of taverns in the community, Boyer wrote that the arrival of the tax collector at the local tavern was a major event, attracting the surrounding property owners who were obliged to account for their property. I do not have a copy of tax returns for Amwell Township prior to 1780, but in that year, the tax collector visited Amwell twice, once in January-February and a second time in June. If only he had made note of the tavern he went to.

In January 1780, Jacob & ‘Jno’ Mattison were taxed on 254 acres, 6 horses, 5 cattle, 5 hogs, and property valued at £189.17. The following June they had added one cow, but their property’s value was reduced to £159.17. Also taxed that year was Joseph Mattison, who was listed as a householder, with 7 lots of land, 2 horses, 3 cattle, 1 hog, and a tavern; no value was listed. By June, he had added five more pigs.

Joseph Mattison

As mentioned above, the earliest record we have of Joseph Mattison getting a tavern license is in 1777.7 By 1777, Joseph Mattison (1742-1823) was 35 years old, which suggests to me that he had been keeping a tavern well before that year. Joseph Mattison married in 1768 Catharine Bodine (1742-1810), daughter of Abraham Bodine and Martje Low. They had four children—the eldest, Catharine (1770-1854) married another tavernkeeper, Alexander V. Bonnell in 1793.

After the Revolution

The Courthouse

With the new country established and the Revolution concluded, people were ready for changes. The first courthouse and county jail for Hunterdon County had been located in Trenton since 1740, and by 1780s had fallen into disrepair. As Kathleen Schreiner wrote:

The inhabitants of the county petitioned the Legislature of the State to allow them to meet in Flemington. They met there informally until 1790 when an election was held to determine where the new courthouse and gaol should be built.8

Flemington, like the rest of the nation, took on a new appearance based on its new function as a county seat in a new country. For the elected Chosen Freeholders, that meant it was time to put up a new building for county business.

One of the early tavernkeepers in Flemington was George Alexander (c.1745-1800). In 1779 he bought a lot of 6.5 acres from Sheriff Samuel Tucker, who had seized it from Joseph Smith, an absconding debtor. Smith, who had been sued for debt by Jacob Mattison, had purchased the lot in 1773 from Thomas Lowrey and Gershom Lee, and they got it in 1766 from another sheriff selling off the property of Samuel Fleming. It was located along the west side of Main Street.

On March 15, 1791, George Alexander, Innkeeper, sold to the Board of Justice and Chosen Freeholders of Hunterdon County for a mere 5 shillings and other consideration a half-acre lot. The deed9 is a little hard to read but stated that “the Court House and Goal of the county is much out of repair,” and that the Legislature had passed a law on May 26, 1790 allowing “the Inhabitants of the County of Hunterdon” to meet temporarily “at the house of John Meldrum . . . at the place called Ringo’s Tavern,” until a location for a courthouse was chosen. A vote was taken in October of that year naming Flemington as the location for the courthouse. Then comes a couple paragraphs that are either cut off or illegible. But the text resumes with this:

A lot of one-half acre, being part of a lot whereon the said George Alexander lives and on the southeast and thereof and on the road leading to Trenton and also butting on the road as now used leading round the said lott to Howells Ferry on Delaware River and the other two sides butting & bounded on other parts of the sd George Alexanders lott.

It is thought that prior to 1790, the Freeholders and Justices occasionally met in Alexander’s tavern. An alternative meeting site may have been Jacob Mattison’s tavern across the street. Perhaps the loss of that business convinced him that it was time to sell his tavern lot.

On April 11, 1793, Jacob Mattison, “yeoman of Amwell,” sold his one-acre tavern lot to Samuel Taylor, carpenter of Amwell for £21.10 This deed included a very nice recital going back to the sale of 147 acres to David Eveland by the heirs of William Penn.

A more likely reason why Mattison sold the tavern lot was his advancing age. By 1793 he was 84 years old. On May 15, 1797, Jacob Mattison wrote his will ordering that he be buried next to first wife Ann in the burying ground by the Old Presbyterian Meeting House in Amwell. He named son John and stepson David Bishop his executors and ordered them to sell his real estate. After bequests of £100 to each of his three sons: Joseph, James and John, the remainder of the money from the sale of property was to be divided equally between his seven children—the three sons plus daughters Elizabeth, Mary, Sarah & Martha.11 Mary, Sarah and Martha each died before their father wrote his will; his bequests went to their children.

John Jacob Mattison died on Dec. 8, 1804, at the remarkable age of 95, and was buried in Pleasant Ridge Cemetery in East Amwell, next to his wife Ann. I had originally thought that the instruction to bury him in “the Old Presbyterian Meeting House in Amwell” meant the Presbyterian Church at the north end of Main Street. But in fact, the ‘old meeting house’ was the Amwell First English Presbyterian Church, located near the village of Ringoes.12

Samuel Taylor

Jacob’s son Joseph Mattison continued to obtain tavern licenses during the early 1800s, but he must have been keeping tavern somewhere else, because Samuel Taylor, the new owner of the tavern lot, also obtained licenses, although the first one on file is not until 1796. Charles Saxton and John Anderson were his sureties.

Copies of the actual license petitions are not available until 1801. They include the signatures of people who supported the applicant, and I am delighted to say they are original signatures, not a clerk’s copy.13 Unfortunately, the licenses for 1801 do not include Samuel Taylor. A possible alternate tavernkeeper for the Mattison lot was Joseph Atkinson who did obtain a license that was signed by mostly Flemington area men: H. Hicks, Thomas Williams, Henry Bailie, Alex. Bonnell, Peter Obert, Asher Atkinson, Samuel Groff, John Sharp, Jr., John Hall, Isaac Passand, Peter Coolbaugh.

Joseph Mattison also got a license in 1801 for which he was charged only $10, which makes me doubt his tavern was on Main Street. Taverns on prominent roads were usually charged more than taverns in out of the way villages because they were sure to attract far more business than out-of-the-way taverns.

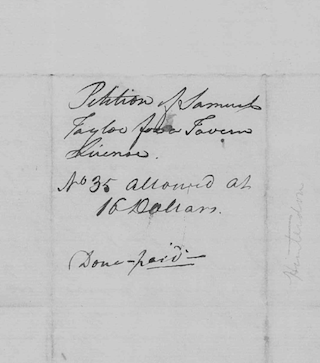

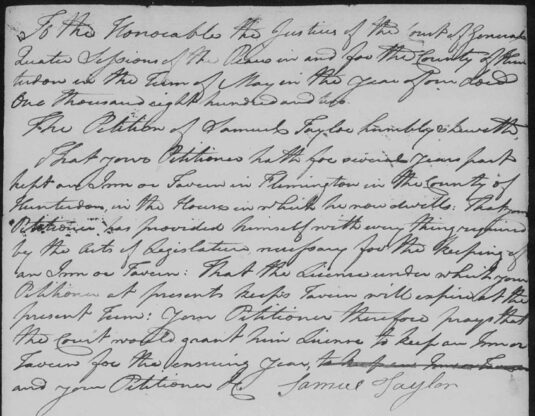

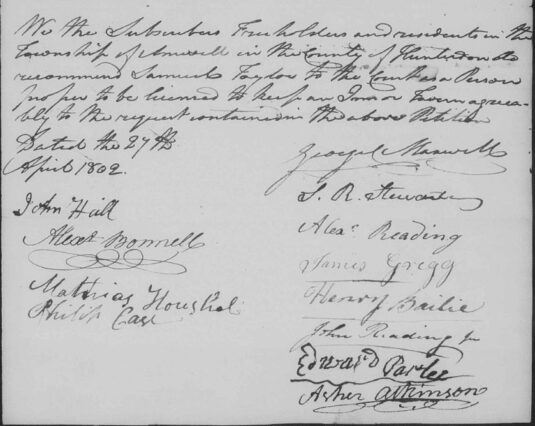

Samuel Taylor did get a license in 1802, at his place of residence in Flemington. He was charged $16 and the men who signed his petition were: John Hall, Alex, Bonnell, Mathias Houshel, Philip Case, George Maxwell, S. R. Stewart, Alex Reading, James Gregg, Henry Bailie, John Reading Jr., Edward Parlee [shakiest handwriting ever!], and Asher Atkinson. Here is a view of that application:

Samuel Taylor did get a license in 1802, at his place of residence in Flemington. He was charged $16 and the men who signed his petition were: John Hall, Alex, Bonnell, Mathias Houshel, Philip Case, George Maxwell, S. R. Stewart, Alex Reading, James Gregg, Henry Bailie, John Reading Jr., Edward Parlee [shakiest handwriting ever!], and Asher Atkinson. Here is a view of that application:

Samuel Taylor (c.1768-1809) was the son of William Taylor and Mary Swallow of the Mt. Airy neighborhood in Amwell Township. (They appear in my article “The Bosenbury and Taylor Graveyards.”) In 1805, William Taylor was among those who subscribed $2 for a survey of the “Trenton Road” (i.e., Main Street in Flemington) by Nathaniel Saxton.14 Two years after the death of Jacob Mattison, Samuel’s father William Taylor wrote his will (dated Oct. 8, 1806) in which he left his homestead plantation jointly to his sons Jacob and Samuel. William Taylor died in March 1807. His widow survived until Dec. 1818.

Samuel Taylor (c.1768-1809) was the son of William Taylor and Mary Swallow of the Mt. Airy neighborhood in Amwell Township. (They appear in my article “The Bosenbury and Taylor Graveyards.”) In 1805, William Taylor was among those who subscribed $2 for a survey of the “Trenton Road” (i.e., Main Street in Flemington) by Nathaniel Saxton.14 Two years after the death of Jacob Mattison, Samuel’s father William Taylor wrote his will (dated Oct. 8, 1806) in which he left his homestead plantation jointly to his sons Jacob and Samuel. William Taylor died in March 1807. His widow survived until Dec. 1818.

Samuel Taylor did not get a license after 1804. In 1805, Joseph Atkinson was licensed to run the tavern “formerly Samuel Taylor’s.” But the next year, the tavern was run by William Bennet, Jr. at a fee of $18. Bennett got the license because on April 7, 1806, Samuel Taylor of Flemington sold the tavern lot to William Bennett, Jr. & Henry Reading, also of Flemington, for $2,000.15 Perhaps he chose to do this because of a degenerative disease, as Taylor died the following March 1809, only 41 years old.

The deed from Taylor to Bennet described the property as “the same lot or parcel of land which Jacob Mattison sold to sd Taylor on April 11, 1793.” It bordered Lot 9 “now the property of Dr. William Geary,” George C. Maxwell, and Henry Bailey. The deed was not recorded until August 29, 1807.

William Bennet, Jr.

William Bennet, Jr. (c.1760-after 1828) was the eldest son of William Bennett, Sr. and wife Ruth. Ruth died in 1798 after giving birth to nine children. Bennett Sr.’s second wife, whom he married on May 13, 1799, was Elizabeth Griggs, widow of an unknown Case.16

William Bennett, Jr. married on Oct. 10, 1801, Rebecca Reading, daughter of John Reading and Isabella Montgomery. Her siblings included John Reading Jr., husband of Elizabeth Hankinson, and Charles Reading, husband of Abigail Hunt, both of whom turn up in early deeds for Flemington properties. After John Reading’s death, Isabella married Henry Baillie, another investor in Flemington properties.

Bennet was one of the Revolutionary War veterans marching in the parade to celebrate the Jubilee of July 4, 1826. (See The Jubilee of 1826.)

William Bennet, Sr. wrote his will on the same day that William, Jr. bought the Flemington tavern from Samuel Taylor. William, Jr. was named an executor of his father’s estate along with his brothers-in-law Cornelius Vanhorne and Samuel McNair. William Sr. died on April 11, 1808 and was buried in the Presbyterian Cemetery in Flemington. His wife Elizabeth died at about the same time. I could not find anything about when William Jr. and wife Rebecca died or where they were buried.

Although William Bennett obtained a tavern license in 1806, he must have lost interest in tavern-keeping fairly quickly because on March 16, 1807, he sold the one-acre tavern lot to John James of Trenton for the same $2,000 that he paid for it.17 But James did not obtain a tavern license. As a resident of Trenton and later of Nottingham, in Burlington County, he could not run a tavern in Flemington because the law required that tavernkeepers live in the building being used as a tavern.

Clearly, James had to hire someone to keep the tavern. There were four functioning taverns in Flemington in 1807, a sign of how important taverns were to their communities.

The other tavernkeepers in the Flemington area in 1807 were Alexander Bonnell, John Muirhead, Samuel Britton and John B. Mattison. Bonnell, who paid $18 for his license, was running the tavern kept by George Alexander. I cannot say at this time where Muirhead’s tavern was, but he was getting licenses the same years that tavernkeepers of the Mattison tavern were, so I eliminate him. Mattison paid $12 for his license, suggesting it was not located on Main Street. Samuel Britton paid $18 to keep “the house lately kept by George Rea,” and Snider had gotten licenses from 1803 through 1806, so that seems to eliminate Britton.

However, in 1808, Neal Hart got a license to run the tavern “lately occupied by Isaac Servis,” for which he paid $18. The license previously obtained by Servis was also in 1808 and was designated as the tavern in Flemington run “last year by Samuel Britton.” I am left with an unsolved mystery about who ran the tavern while James owned the property. But by 1810, all will become clear, as I will describe in Part II of The Union Hotel.

The story continues with Union Hotel, part two.

Footnotes:

- West Jersey Proprietors Surveys, NJ State Archives, Book A folio 132. ↩

- NJSA, Deed Book X fol. 516; confirmed in the recital of Hunterdon County Deed Book 1 p.592. ↩

- James P. Snell, History of Hunterdon County, p. 326. ↩

- Snell, p.310. ↩

- Recital, Hunterdon Co. Deed Book 1 p. 592. ↩

- According to the author of the section on Flemington in Snell’s History of Hunterdon County. ↩

- From the Index list of licenses on file at NJ State Archives. That is the only license they have for Joseph Mattison, but he was taxed as a tavernkeeper in 1780, 1786 and 1790. ↩

- Kathleen J. Schreiner, “Our Courthouse,” Hunterdon Historical Newsletter, Winter 1978. ↩

- H.C. Deed Book 1 p.584. ↩

- H.C. Deed Book 1 p.592. ↩

- Elizabeth (1731-1809) was the widow of John Anderson and wife of Thomas Jones. Sarah (c.1736-bef. 1795) was the wife of Isaac Gray. Mary (c.1740-bef. 1809) was the wife of James Stout and mother of Samuel Stout). Martha (1742-bef. 1795) was married to Jesse Hart. ↩

- Members of the Mattison family buried there are Jacob John (1709-1804); Ann Hankinson Mattison (1709-1761); Joseph Mattison (1711-1745); Ann Bishop Mattison (1717-1748) and John Mattison (1740-1745). ↩

- They are available on the Family Search website, under Hunterdon County, Business records and commerce. ↩

- The Saxton Papers, HCHS, Ms. Collection, #0005, box 3 folder 56. ↩

- H.C. Deed Book 14 p.199. ↩

- On Oct. 24, 1799, Elizabeth and new husband William Bennett petitioned the Orphans Court to allow John Runkle to have guardianship of her children, John, Hannah & Rachel Case, all minors. He other children, Henry, Ann, Mathias & Elizabeth, being between the ages of 14 and 21, chose Charles Reading as their guardian. ↩

- H.C. Deed Book 14 p.222; also, the recital in Deed Book 16 p.434. ↩