This article by Egbert T. Bush describes an old sawmill on the Wickecheoke located on a perilous little road, known appropriately as Old Mill Road in Delaware Township.

I have added comments with additional information and also some additional headings due to the considerable amount of information that Bush included in this article. If there is one lesson to be learned from this saga, it is that in certain neighborhoods in the 19th century, there were only one or two degrees of separation, not six.1

Big Distilling Business Once Thrived Along Laborious Wickecheoke Creek

“Jersey Lightning” Makers

by Egbert T. Bush, Stockton, NJ

published January 8, 1931, Hunterdon County Democrat

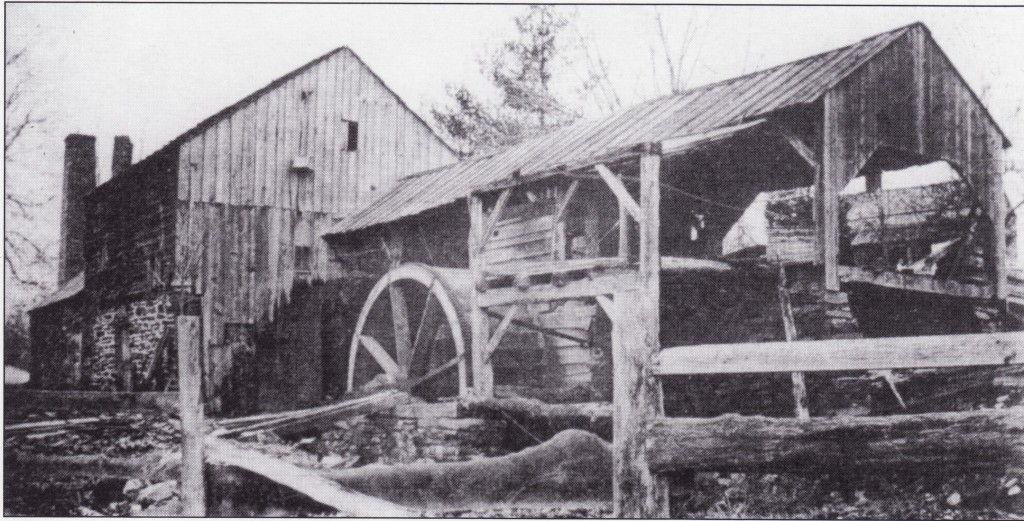

On that erstwhile laborious stream, the Wickecheoke Creek, about one mile southwest of Locktown, stands an old mill that has been there for generations. Who built it or when it was built, nobody appears to know, and no reliable records have been found, but it was evidently there much over a century ago. In truth there were in older times two mills running there, one cutting up logs and the other grinding grists for the community.2

And still another industry was carried on at the same place. The surplus apples of the vicinity—reputed to have been plentiful in those days—were converted into that standard article of early commerce, “Jersey Lightning.” Old people still tell of carting apples to this distillery and getting very satisfactory results therefrom. This branch of the business was carried on until near the end of the past [the 19th] century.

We find that by deed dated August 13, 1818, Andrew Bray conveyed to Elisha Rittenhouse 112 acres of land “Beginning at a hickory sapling on the north side of the mill dam,” and apparently including the mills, but mentioning only the Wickecheoke and the dam. It would seem from other references, that the mill was there before the year 1800.

This probably explains Mr. Bush’s confusion. The property had gone out of the Rittenhouse family in 1801, when Elisha Rittenhouse and Thomas Opdycke did a land swap, and Opdycke got the mill. In 1818, Elisha Rittenhouse, John Opdycke and Henry Trimmer, as commissioners to divide the real estate of Thomas Opdycke deceased sold the mill property to Andrew Bray, the son-in-law of Elisha Rittenhouse, who promptly conveyed it back to him individually for the same price–$40/acre. Back in 1790, Elisha Rittenhouse was taxed with his father Peter on 206 acres and a grist mill. In 1780, Peter Rittenhouse was taxed in Amwell Township on 206 acres and a sawmill. Peter wrote his will in 1791 and left to his beloved son Elisha all his lands and tenements. But the mill could go back as far as the 1740s. In 1767, William Rittenhouse, the first of the family to settle in Amwell Township, and the one who bought the land in 1734, bequeathed to his son Peter, in addition to lands already deeded, a sawmill and 100 acres along the Wickecheoke Creek, for a total of 240 acres.

Myers Long An Owner

April 1, 1847, John T. Risler, Executor of Elisha Rittenhouse, conveyed 7 acres and 10 perches of land to Tunis Myers; “also the right to clean the tail race above the described boundaries as it runs at this date, to be included in the above described land as belonging thereto as part and parcel of the same, it being a Certain Mill Lot which the said Elisha Rittenhouse did order and direct his executor to make sale of in his last will and testament dated the 30th day of April, 1846.”

Tunis Myers has long bedeviled me. I have yet to identify his parents. Keturah Rittenhouse, his wife, was born Sept. 1823 to Alanson Rittenhouse and Mary Ellen Sebold, and was the granddaughter of Elisha Rittenhouse, thus making it logical for Tunis Myers to become involved in the ownership of the mill. Tunis Myers was born November 1807 in Morris County, NJ. That is the birthplace given in the 1875 N.J. State Census. However, in his obituary of Sept. 5, 1901, he is identified as “a native of this (Delaware) township.” Even more annoying, in the 1880 census, the birthplaces of Tunis Myers’ parents was left blank, which was very unusual. The 1900 census shows that they were born in New Jersey. There was another Tunis D. Myers, son of Peter Mires and Elizabeth Dilley, who acquired property on the South Branch, married Ann Naylor, and was about the same age as Tunis the miller, adding to the confusion. Much of the problem comes from the fact that many of the Myers who lived in Amwell Township in the first half of the 19th century did not write wills.

Here Tunis Myers carried on the varied industries until 1871. Then he and his wife Katurah conveyed the property as above to Anderson Bray and William S. Cobb.

Tunis Myers was listed as a miller in the 1870 census, but as a farm laborer in the 1880 census. Tunis and Keturah Myers remained in Delaware Township until 1890, when they departed for Waterloo, Nebraska, where Tunis Myers died on August 23, 1901, and his wife Ketura sometime afterwards. Anderson Bray was the son of Andrew Bray, mentioned before.

This partnership lasted only two years. March 25, 1873, William S. Cobb and Adelia W., his wife, conveyed their interest to Anderson Bray for $1,000.

Mr. and Mrs. Cobb seem to come out of nowhere. They appear in the 1880 census for Delaware Township, William age 48, a farm laborer, and wife Adelia 26; both of them born in Pennsylvania. A further search of census records was fruitless. However, William S. Cobb died on November 17, 1893, and was buried in the Sandy Ridge Cemetery. When his wife died or where she was buried I cannot say.

On the same day Anderson Bray conveyed the entire interest to Adelia W. Cobb for $2,000. Just why this was done is left to conjecture—and conjecture is sometimes preferable to certain knowledge and often much more plentiful.

It should be noted that Anderson Bray made a cool $1000 on the transactions.

Robert Holcombe and Mrs. Pegg

Robert Holcombe, who was Chosen Freeholder for Delaware Township over 40 years ago, whose re-election (as memory serves) occurred on the Tuesday following the blizzard of 1888, operated the mills and the allied industry for a long time.

Robert M. Holcombe, born September 17, 1835 to George N. Holcombe and Matilda Case, married on October 9, 1858, Lydia Chamberlin, daughter of Sheriff Ampleus B. Chamberlin and Elizabeth Myers. There must be a relationship between Elizabeth Myers and Tunis Myers, the miller that Bush is writing about here, but I cannot explain it. Elizabeth’s parents did not marry until July 15, 1808, which is too late for Tunis if he really was born in 1807 in Morristown.

Whether he actually ever held title to the property or not seems difficult to ascertain. Anyhow, he was so long and so closely connected with the place and its industries that it is still commonly called “Holcombe’s Mill.”

In the 1880 census, while Mrs. Cobb owned the mill, Robert Holcombe was identified as a miller. I will have to do a deed search to find out who Mrs. Cobb sold it to. Robert Holcombe died in 1891. Jonathan M. Hoppock wrote that the mill was owned by Mrs. Mathias Pegg in 1906 and was still in working order, but had already been made unnecessary by technological advances. Mathias Pegg died sometime after 1900 (he was counted in the census that year as a farmer), but apparently before 1906. In 1910, the widow Pegg was living with her grandson John W. Pegg laborer. Mrs. Pegg was Rebecca Jane Carrell, daughter of John Arnwine Carroll and Amy Myers. Amy Myers was the daughter of John Myers and Sarah Rockafellar. Her sister was Elizabeth Chamberlin, mother of Lydia, and mother-in-law of Robert Holcombe, the miller. Which means that Mrs. Rebecca Carrell Pegg was Lydia Chamberlin Holcombe’s first cousin. Got that? So although I do not have much information on Mathias Pegg, it is clear that Mrs. Pegg’s ownership of the mill was all in the family, so to speak.

We find that letters of administration on his estate were granted February 9, 1892, to Anderson Bray and William B. Hockenbury. Since that time the property has passed through various hands and is now interesting, not so much for what it is as for what it has been, for its varied industries and the operators all now of the past.

Tells of Working on Mill

Our aged friend, Theodore Holcombe, now living in Trenton, son of the old time Theodore Holcombe, millwright of Quakertown, tells of helping his father build a water wheel for this mill and make various repairs thereon, in 1864 or 1865. He says that about that time they also built a 24-foot, 60-bucket wheel for the grist mill at Green Sergeant’s. This was evidently the wheel that lasted until recent years, gradually rotting and falling away.

Bush does not say whether Theodore Holcombe and Robert M. Holcombe were related. I have not found a direct connection. By this time, members of the Holcombe family were very numerous in Hunterdon County.

Theodore tells interesting stories of his experience while helping his father do work as a millwright, tho he himself never adopted this as his life work. He relates that soon after this they built two wheels, one 22 feet in diameter, and the other 24 feet, for Peter Shepherd and Son, to be used in their mills near Rocktown. For some reason these wheels were made in Quakertown, the home of the makers, and transported in the “knock-down” to the old mill of the Shepherds at “Old Amwell,” where they were set up for business, probably to be the last used there. For that interesting old place, like so many others, is now only the ghost of what it was in the good old days.

Old Amwell was a village on the hill south of Ringoes, just east of today’s Rte 31.

The Distillery

But the Holcombe Mill was far from having anything like a monopoly of the distilling business in its vicinity. Another distillery was on the farm now owned by Maxwell Snyder, only a short distance away. The foundation of the building is still easily seen by all who pass the spot in going along the “Pine Hill” road, from Sergeant’s Mill to Locktown. It was a neighbor so close to the Holcombe Mill that we might doubt about their being operated simultaneously. But it does appear that at least a part of the time, this was the case; and we must remember that there was then a wide and imperative demand for this particular product of the mills. It does appear that this had much to do with keeping up the spirits of many good people, thru all their contests and discouragements, from colonial days until—well, almost until everything above one-half of one percent was driven out ten years ago.

Bush is referring to Prohibition; 0.5% was the amount of alcohol allowed in medications like cough syrup.

“Uncle John Hice” and the Dalrymples

Among those remembered for making the precious stuff within the bounds of that old foundation is “Uncle John Hice,” who bought the farm of Philip Gordon April 18, 1830, 72 ¼ acres for $1,650.50.

This could not be the distillery lot, since Gordon advertised its sale in the Gazette on Jan. 3, 1838, on a farm of 110 acres.

February 3, 1849, after selling off 2 ¼ acres, Hice conveyed the farm to Garret Bellis for $2,200. In 1856, this John Hice bought what has since been known as the “Hice Lot,” near Headquarters, whereabout he is well remembered by old people.

March 18, 1857, Garret Bellis conveyed the distillery farm to Jacob C. Johnson for $3,500. In October of the same year, Johnson conveyed it to Peter Dalrymple for the same consideration. In 1905, Lucinda Dalrymple conveyed the same property to Maxwell Snyder for $1,200.

A later deed refers to the stillhouse of Peter Dalrymple deceased, located on Plum Brook.

Maxwell Snyder doesn’t seem to be part of the neighborhood, but he married into the Smith family of Locktown. Bush has left a gap between Peter Dalrymple and Lucinda Dalrymple. Peter Dalrymple (1815-1859) was a Kingwood farmer married to Lucinda Shepherd (1818-1906). He probably moved to the Pine Hill Road farm when he bought it, and died there at the age of 44, leaving five children and his widow Lucinda. She remained there until shortly before her death at age 88.

This deed says: “Beginning at a stone for a corner . . . in the public road leading from Mier’s Mill to Locktown . . . the same having been conveyed by Richard Shepherd and Andrew B. Rittenhouse, executors of Peter Dalrymple, to Lucinda Dalrymple April 1, 1862.” The description came down from the deed of 1830, excepting 2 ¼ acres sold by Hice.

I have not identified the parents of Peter Dalrymple or of Richard Shepherd, but if they’re not related to everyone who’s come before in some way, I’ll eat my hat.

The Williamson Farm

We find that Samuel Williamson, “acting as executor of William Williamson, deceased,” conveyed 396.16 acres of land here, including the above farm, April 1, 1812, to Alexander Bonnell, Nelly Quick and Thomas Gordon, for $7,923.20.

This old deed is of special interest because of its lengthy explanations. One of these is that at the time of William Williamson’s death, the property lay as containing 290 acres. This appears to have been long accepted as the true area; but there was a suspicion that the lengthy boundaries contained more land. A survey was accordingly made, and the true area was found to be 396.16 acres. No wonder somebody’s eye saw the discrepancy; a 106-acre patch seems entirely too big to pass unnoticed as an attachment to a farm of 290 acres.

The Court Intervenes

But this is not all that makes the deed interesting. It tells us that Samuel the executor, secured at one time a bid of 60 shillings per acre for the plantation; but the bidder insisted that the calculation be made on the old accepted area of 290 acres instead of the area newly found. The deal was never closed and Samuel took possession of the property as executor and guardian of the estate, managed it himself for some years, and then deeded it to a “go-between,” who promptly conveyed it to Samuel.

This gave rise to a suit in Chancery, the result of which was that both deals were declared void, and the executor was ordered to sell the property to the highest bidder in open market. The sweeping opinion of the Chancellor with regard to the conveyance by an executor to a fictitious purchaser to be actually conveyed back to himself is of special interest. Whether the law in this matter is still as strict as seems to be implied in this sweeping opinion may well be left to those learned in the law; but there can be no doubt that all must be done openly and for the best interest of the estate.

The saga related to the Williamson family over the rights to this old Delaware Township plantation on Pavlica Road is just extraordinary; a perfect local example of the slow wheels of justice described by Charles Dickens in Bleak House. I hope I live long enough to write about it here.3 Bush’s concern over those “fictitious purchasers” is interesting. A similar practice, in which a trustee sold a deceased’s property to a relative, and then personally bought it back for his own use, was quite common.

The Gordons

A part of this great tract came later into the hands of Thomas Gordon, namely the Hice farm as purchased {by Hice} in 1830. Thomas Gordon’s two sons, Othniel and Thomas, conveyed their interest to Philip Gordon, September 16, 1817 for 331 pounds, eleven shillings and eleven pence, and Philip conveyed it to Hice.

Philip Gordon (1788-after 1839) was the son of Franklin Gordon, who was the brother of Othniel and Thomas Gordon.

Smith Ent of Upper Creek Road

Back in those earlier days, Smith Ent owned the farm farther along on the same stream, later known as the Calvin Snyder farm. Here he not only did farming in the accepted way, but in connection therewith operated a distillery of no little importance to the farmers of the community, who had plenty of apples and not much else that they could do with them. A good many apples could be stored in a barrel of whiskey and, if let alone, would keep until there was more or less of a scarcity.

The Oregon Mill

At another mill not far away, tho on the Lackatong instead of the Wickecheoke, was another distillery. This was at the “Oregon Mill,” later known as Strymple’s Mill.

This is an unusual spelling. The family name and the road name are usually spelled Strimple.

This, too, is said to have been a valuable adjunct to the regular business, tho little definite information concerning either business is now available.

The names “Oregon Mill” and “Oregon School District,” only two or three miles apart, set one to thinking how strong was the hold of the Oregon region upon the minds of our people a few years before and a few years after 1850. All that region and southward along our coast was a land of mystery and dreams; a land accessible only by weary weeks of sailing or by months of suffering on the land route, marked by the graves of those who had fallen victims of hardships or of savage hostility; a land from which news could be received only at long and uncertain intervals. The changes are startling. Now we can go back and forth by train, by automobile or by air. And instead of waiting months for news, we sit at home and listen to the shouts of 90,000 “fans” over a game of football, as it is played within sound of the Pacific’s waves.

Times Have Changed

It is a long jump from having a busy mill on every mile or so of every available creek, to having scarcely one mill to every ten of such streams; from “proof” liquor pouring thru a cooling worm at every turn, to finding no such worms at all;4 from the ox-train and the prairie schooner, to the airplane of today; from waiting months for news from our western coast, to tapping the overburdened air by means as simple as turning the spigot in the old cider barrel, and letting the news of the moment pour into our own homes!

And the thought that all this change has been wrought within the span of a man’s life, sets one to wondering what life will be like at the end of four score years to come. The result is a dizzy bewildering, meaningless maze of conjecture. But we may be assured that the people of those days to come will be as little fitted for the rigors and slowness of our lives, as the most modern of our day are for the hardships and inconveniences of four score years ago. No doubt every “present” age is best for those who breathe its air; and it is quite certain that there never has been and never can be a perfect or contented age.

I find Bush’s meditations on what people were like before the Civil War, compared to what they were like when he was in his 80s, very moving. He seems here to be predicting the advent of couch potatoes. I am glad he was spared that.

Footnotes:

- Jonathan M. Hoppock also wrote about this mill, very briefly, here. ↩

- I am surprised that Bush did not know who the original owners of this mill were. The property belonged to the Rittenhouse family as early as 1734, when it was acquired by William Rittenhouse. ↩

- Eventually I did write about the farm in The Pine Hill Cemetery and Pine Hill Cemetery Revisited. ↩

- A ‘worm’ was a spiral pipe in which liquor was condensed from a still. ↩

Chuck Cline

March 10, 2012 @ 12:02 pm

Part of my grandfather’s farm, Erva Cline, was referred to as the Williamson Lot and has the foundations of two buildings. Could this be part of the Williamson tract referred to on Pavlica Road?

Marfy Goodspeed

March 10, 2012 @ 1:49 pm

Chuck, It is possible that a tract of 133 acres that ran from south of Reading Road north to Pavlica Road was owned by the first William Williamson, between the 1730s and about 1750 when his daughter Margaret married Daniel Larew. After that time, Margaret and Daniel Larew were the owners, but I have found no deed to confirm that. By 1811, when the Williamson Court Case was first being tried, this Larew tract was no longer part of the land in dispute.