This next chapter in the creation of Delaware and Raritan Townships involves a lot of politicking, a lot of ‘inside baseball.’ But it is the story behind the story, and should not remain hidden. I’ve leavened the article with some passing references to mad dogs, passenger pigeons and Lincoln’s first speech. The previous episodes in this saga can be found here: Part One and Part Two.

An Angry Letter

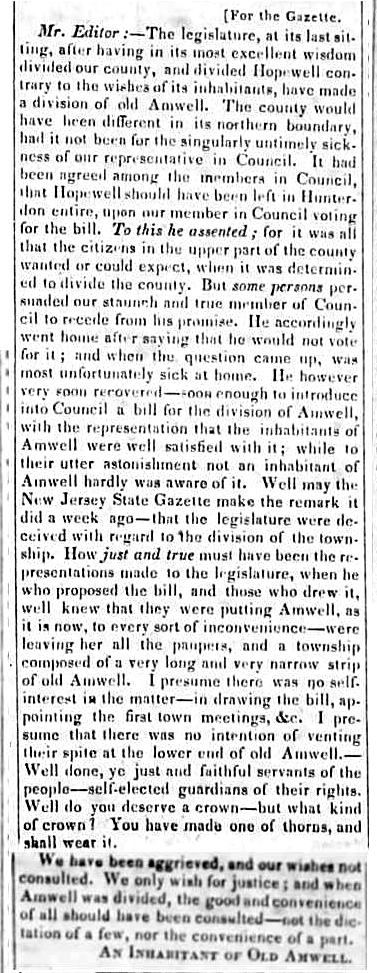

After news broke in the Hunterdon Gazette about the Legislature’s high-handed division of Hunterdon County into Hunterdon and Mercer Counties, and of Amwell Township into Delaware, Raritan and what is now East & West Amwell, letters began pouring into the editor’s office at the Hunterdon Gazette.

One of the letters was from “An Inhabitant of Old Amwell,” another pseudonymous writer, who laid the blame for the division on a member of Council he declined to name, but happened to be Joseph Moore of Hopewell. He wrote that “The county [Mercer] would have been different in its northern boundary had it not been for the singularly untimely sickness of our representative in Council. It had been agreed among the members of Council that Hopewell should have been left in Hunterdon entire, upon our member in Council voting for the bill. To this he assented, for it was all that the citizens in the upper part of the county wanted or could expect, when it was determined to divide the county.”

But then “some persons persuaded our staunch and true member of Council to recede from his promise. He accordingly went home after saying he would not vote for it; and when the question came up, was most unfortunately sick at home.”

It appears that at first the Whigs persuaded Joseph Moore to vote for the new county by promising to attach Hopewell (a Whig town) to a Democratic county (the remainder of Hunterdon). On February 14, 1838 the Gazette reported that “The New County Bill was to be reported in Council on Monday. It is said that an amendment has been introduced into the bill, by which Hopewell township will remain with Hunterdon.”

But then someone decided to divide Hopewell between the two counties; the northern half kept the name Hopewell and went with Hunterdon County; the southern half was given the name “Marion” and attached to Mercer County. The boundary ran right through the middle of Pennington. (This division was undone the following year, when all of Hopewell was attached to Mercer County.)

The “Inhabitant of Amwell” seemed to think Joseph Moore had a hand in that decision to divide Hopewell, and his claims of illness were deceitful. After all, Moore, being a Democrat, could not appear to support this Whig maneuver. But he couldn’t vote against it either.

Perhaps this was because he had some dealings with the Whigs. As it happens, he was “the maverick Democrat from Hunterdon,” according to the New Jersey Gazette, who had joined with the Whigs to shut down the legislature in the winter of 1837-38. That was when the Whigs first took a majority in the Council and were flexing their muscles by refusing to meet with the Assembly. Since Hopewell residents tended to have Whig sympathies, Moore’s behavior in 1837 is not so surprising. The new county bill was passed into law on February 22, 1838.

Democratic Power Brokers

I do not know who persuaded Moore not to vote for the bill, but the Democratic party bigwigs at the time were Peter D. Vroom, Stacy G. Potts and Garret D. Wall. Some of the prominent Democrats in Flemington were lawyers: Peter I. Clark, Alexander Wurts, John T. Blackwell and Andrew Miller. They were all likely to lean on Councillor Moore.

Also exerting pressure were probably the Democratic members of the Assembly from Hunterdon (John Hall, James A. Phillips, David Neighbor and Jonathan Pickel). The fifth member of the Assembly was John H. Huffman, who was aligned with the “anti-Caucus ticket.” Anti-Caucus Democrats were essentially disillusioned Democrats who had not yet joined up with the Whigs.

The “Inhabitant of Old Amwell” went on: “He [Joseph Moore] however very soon recovered [from his supposed illness]– soon enough to introduce into Council a bill for the division of Amwell, with the representation that the inhabitants of Amwell were well satisfied with it; while to their utter astonishment not an inhabitant of Amwell hardly was aware of it. Well may the New Jersey State Gazette make the remark it did a week ago – that the legislature were deceived with regard to the division of the township.”

Was Joseph Moore just making this up—that the residents of old Amwell were happy to be divided, or was this something that political operatives had assured him of? Was he an actor in this drama or was he duped? Some things we will never know for sure, but the “Inhabitant of Old Amwell” had little doubt that Moore was in on the schemes, and was the one who should take the blame.

The Division of Amwell

In his letter, the “Inhabitant of Old Amwell” asked: “How just and true must have been the representations made to the legislature, when he who proposed the bill, and those who drew it, well knew that they were putting Amwell, as it is now, to every sort of inconvenience – were leaving her all the paupers, and a township composed of a very long and very narrow strip of old Amwell.”

The “long and narrow strip” would be the combined East and West Amwell, running along the southern border of Hunterdon County. Why it was that all the paupers were located in that portion of old Amwell Township I cannot say, other than that Lambertville was a likely place for them to live. The canal had been completed in 1834, and some of those paupers may have been canal workers who had no work once the canal was finished. The problem of “keeping the poor” was a major financial issue for local governments in the 1830s.

The “Inhabitant of Old Amwell” concluded by writing: “Well done, ye just and faithful servants of the people – self-elected guardians of their rights. Well do you deserve a crown – but what kind of crown? You have made one of thorns, and shall wear it. We have been aggrieved, and our wishes not consulted. We only wish for justice; and when Amwell was divided, the good and convenience of all should have been consulted – not the dictation of a few, nor the convenience of a part.” The writer was expecting that voters would take their revenge on the legislators who created this travesty. But in the following election, in October 1838, Joseph Moore was re-elected to the Council with a much larger plurality than before, thanks to the re-configured Hunterdon County. He declined to run in 1839.

In 1844, the state legislature was once again controlled by the Democrats, but the votes from Amwell and Hunterdon did not make the difference.

Motivations

It is still a question why those “few designing individuals” who had such influence over Joseph Moore wanted to divide Amwell. Perhaps it was felt that Amwell was just too big and populous compared to the other towns in Hunterdon; it was three times larger in both size and population. But it seems clear from the letters to the Gazette that the division was instigated by the Democrats. They created two Democratic towns to one slightly Whig town. Perhaps they thought this would give them more clout on the Board of Chosen Freeholders, the governing body of Hunterdon County. In the 1830s, each town sent two ‘chosen freeholders’ to sit on the Board.

If the County Board of Freeholders objected to these events, they did not memorialize their feelings in the minutes of their meetings. James Johnson Fisher, who represented the new township of Delaware on the Board of Freeholders, was the chosen freeholder of old Amwell in 1837. The other freeholder from Delaware in 1838 was James Snyder, who was elected to the State Council the following year as a Democrat. (James Johnson Fisher could not get elected to the Council because he was in the minority as a Whig.)1

It should be noted that in 1844 when the Democrats came back into power, they outdid the Whigs by creating six new townships and two new counties. In addition, they changed the borders of existing counties, first by adding Hopewell, which had been part of Mercer, to Hunterdon, and second by adding Tewksbury to Somerset. The following year they undid their work and returned Hopewell and Tewksbury to their previous counties.

Who Was Joseph Moore?

Joseph Moore was born about 1780 to Ely Moore and Elizabeth Hoff. He was a miller who lived a short distance east of Marshall’s Corner in Hopewell Township. Joseph Moore suffered a disaster in June 1833 when his “large sawmill” on the Stoney Brook washed away in a flood. Disaster hit again in 1839 when his flour mill burned down. By 1850, he was running a linseed oil mill. His farm and mill complex (the mills are no longer standing) are today part of the Hopewell Valley Golf Club. This put him in the northern half of Hopewell Township, the part that was given to Hunterdon County.

Joseph Moore’s first wife was Sarah B. Phillips, daughter of Thomas Phillips, with whom he had eight children. His second wife was Leah Wilson, daughter of John Wilson and Jennie Deremer. Leah Wilson’s family lived on the Lambertville-Headquarters Road in Delaware Township. John Wilson had fought in the Revolutionary War and died in 1822; Leah’s mother Jane Deremer died in 1834. Leah was still single when John Wilson wrote his will in 1822. She married Joseph Moore sometime after Moore’s first wife Sarah died in 1823.2

Leah Wilson Moore died age 60 in Hopewell in 1841; Joseph Moore died on May 9, 1852. He and his wife are buried in the west side of the Pennington cemetery.

Old Amwell’s Last Meeting

The legislation creating the three new townships stated the law would take effect on April 2, 1838. On that day, the old Amwell Township had its last meeting. An announcement for the meeting was published in The Hunterdon County Gazette on March 14th.

“TAKE NOTICE ! THAT the Township Committee of the townships of Amwell, Delaware and Raritan, will meet at John W. Larason’s on Monday the 2d day of April next, to settle with the several township officers. – All persons in said townships having damage done to their Sheep by dogs, are requested to present their bills to said committee on the day above named before 1 o’clock P. M. If there is not a sufficiency of Dog Tax to discharge said bills, there will be a dividend struck at that time, and those not presented will be disbarred from a benefit of the same. – By order of Town Committee. [signed] J. [Jeremiah] Gary, Clk.”

The wording of this announcement is a little confusing, but the fact is that the new townships had not yet organized, so the Township Committee referred to was the Committee for old Amwell. The meeting intended to close the books on old Amwell’s business.

The principle issue they dealt with was reimbursement to sheep farmers for damage done by roaming dogs. Dogs were taxed as early as 1803 in Amwell Township. Judging by tax returns of the late 18th and early 19th century, very few people owned dogs. Those dogs were taxed to make up a fund to reimburse the sheep farmers. Rabies was a particular concern. On March 15, 1837, the Gazette printed this notice:

“MAD DOGS ─ We are informed that one or two dogs in a rabid state passed through the neighborhood above Flemington last Sunday, and bit some dogs, &c. The alarm has been given, and dogs strolling from home, may run some risk of being captured. Public safety is the first consideration in such cases.”

The problem of dogs attacking sheep continued all through the 19th century. Delaware Township has in its archives records dating to 1892-1896 of claims made for animal damages. Sheep were listed, but also turkeys, geese, ducks and one colt. Generally, two freeholders (in the case of the colt, four) unrelated to the claimant would view the damage and estimate its cost. Then the claimant and appraisers would appear before a justice of the peace or a notary public (or, in one case, a commissioner of deeds) and testify. The value of the livestock ranged from $1.75 for a gander to $5.00 for a sheep to $37.50 for the colt. Amazingly, this system remained in effect until 1970 when an ordinance was passed making owners liable for the damage done by their dogs.

In Other News of 1838

Abraham Lincoln’s First Speech

Thanks to the movie “Lincoln,” we have all been thinking more about Lincoln’s presidency. It is intriguing to note that in January of the year that Delaware Township was created, Lincoln gave his first political speech, entitled (somewhat ironically for us) “The Perpetuation of Our Political Institutions.”3 In the speech, Lincoln was addressing the pernicious influence of mob action as a threat to the survival of our unique experiment in self government, which was then barely 50 years old. He observed that the government was not in danger from a foreign invader, but that the danger must come from ourselves. “As a nation of freemen, we must live through all time, or die by suicide.” After powerfully describing the depredations of mobs in several states, he prescribed a remedy: “Let every American, every lover of liberty, every well wisher to his posterity, swear by the blood of the Revolution, never to violate in the least particular, the laws of the country; and never to tolerate their violation by others. As the patriots of seventy-six did to the support of the Declaration of Independence, so to the support of the Constitution and Laws, let every American pledge his life, his property, and his sacred honor;–let every man remember that to violate the law, is to trample on the blood of his father, and to tear the character of his own, and his children’s liberty.” He observed that when Government itself does not uphold the laws, in this case, by failing to prosecute the mob leaders, “the strongest bulwark of any Government, and particularly of those constituted like ours, may effectually be broken down and destroyed–I mean the attachment of the People.”

Lincoln was not addressing the pernicious effects of cagey politicians working the system to their benefit, but such actions were also undermining the confidence of citizens in their government. And so it goes, up to the present day.4

Passenger Pigeons

In the March 28, 1838 edition of the Hunterdon Gazette, it was reported that “Numerous flocks of wild pigeons have passed over this region of country during the past week. Great numbers of them were caught with nets.” These were passenger pigeons. By “great numbers” the editor meant millions of birds, enough to create the shade of an eclipse. They were easily caught in nets every time they passed by in their spring and fall migrations. By 1870, they had became rare. The last one died in 1941.

- Here’s an issue I have not resolved—the N.J. State Constitution required that only one person represent each town on the board of freeholders. And yet, in the 1830s, towns were each sending two members to the board. ↩

- I have been unable to locate a marriage record for them. ↩

- The speech was delivered to the Young Men’s Lyceum of Springfield, Illinois on January 27, 1838. ↩

- Visit the Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln to see the the full text of this moving speech. ↩