This is part two of a speech delivered on Nov. 16, 2014 for the Hunterdon County Tercentennial. You can find the first installment here.

Moving to Hunterdon

Moving to Hunterdon

I ended the last post with the statement that in 1704, John Reading had a tract of 1440 acres surveyed in the far northwestern corner of the Adlord Bowde purchase. It was an excellent location—superior agricultural soil and access to the river. At this point, the river runs east-west, so Reading’s house could face south as well as face the river, and he had an excellent view of traffic going both ways. He named it Mount Amwell, after his family’s ancestral home in England.1

I took the photo from the Pennsylvania side of the river, at the north end of Hendrick’s and Eagle Islands—it was the only place I could get a good view, thanks to all the trees along the river. This farm is just east of the Lockatong Creek. The stone house on the left was built by or for Reading’s grandson Richard Reading in the later 18th century. John Reading’s house was probably at or near that spot, but it is long gone.

His next challenge was to move his family from Gloucester to Mount Amwell. It’s one thing to travel on Indian paths by horseback. It’s quite another to cart a couple rooms full of Jacobean furniture that distance. Furniture of the late 17th and early 18th centuries was large and very very heavy, being made of hard, dense oak. This furniture was made in England, and is typical of the pieces that a well-to-do family would own. Reading probably brought furniture like this with him in 1684, but it was most likely destroyed in the fire of 1697. I have little doubt that, given his wealth and stature, he managed to replace his furniture with similar items.

It must have taken a few men just to lift those beds, bureaus and tables, and a very large ox cart to transport them, which meant a lot of bushwacking over those Indian paths. This may have been one of the few times that Reading chose to use the Delaware River instead of going over land, but it would have been a hazardous journey, because only shallow boats could navigate north of Trenton.

New Jersey As A Royal Colony

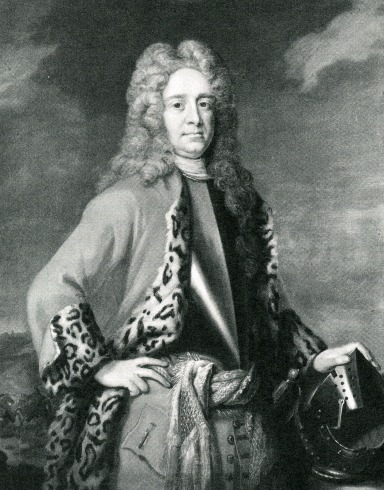

Following unification and surrender of the two Jerseys, the Queen had to name a royal governor. She chose her cousin, Edward Hyde, Lord Cornbury. He had already been named Governor of New York in 1701. Instead of finding a new governor for the new province of New Jersey, the Queen decided to have Cornbury govern both colonies. Having to share a governor was an early insult to New Jersey. The other insult was the governor himself.2

Following unification and surrender of the two Jerseys, the Queen had to name a royal governor. She chose her cousin, Edward Hyde, Lord Cornbury. He had already been named Governor of New York in 1701. Instead of finding a new governor for the new province of New Jersey, the Queen decided to have Cornbury govern both colonies. Having to share a governor was an early insult to New Jersey. The other insult was the governor himself.2

Gov. Cornbury is without doubt one of the most notorious figures in New Jersey history, even if we disregard the charge that he dressed up to look like his cousin, the Queen.3 He had an unjustifiably high opinion of himself, and his high-handed manner of governing did not go down well with the independent-spirited colonists of NJ. His eventual overthrow almost inevitable.

Here is the essential fact of his term in office, and that of subsequent royal governors—land ownership created most of the political conflict and defined the political divisions in New Jersey. (Religion probably comes second.) This is why I labored over the proprietary land system. Cornbury’s closest advisors were gentlemen who wished to abolish it, so that they could amass much larger acreage than was allowed. I’m talking thousands of acres, not just hundreds.

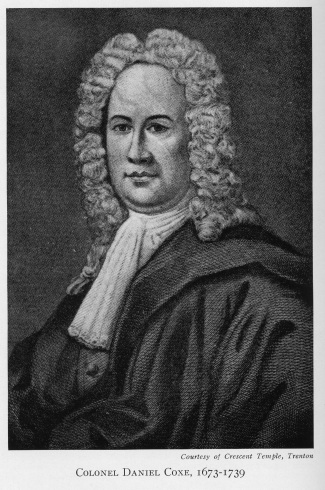

During the early 18th century, even though there were different groups with different interests, they always seemed to coalesce around supporters of the proprietary system or their opponents, who had co-opted Gov. Cornbury with some hefty bribes. Two of these opponents were Daniel Coxe Jr., son of the early governor of West New Jersey, and Peter Sonmans. They and others lobbied actively to have the Council of Proprietors abolished, and they almost succeeded.

Daniel Coxe became a member of the Governor’s Council in 1706, and that year, Cornbury, probably at Coxe’s urging, ordered John Reading, as clerk of the West Jersey Proprietors, to appear before him and explain by what authority the Council was making Indian purchases. The Governor also ordered that the Council of Proprietors could not make any more purchases unless it had the Governor’s approval.

In 1707, Reading and members of the Council presented the Governor with a statement describing how the Council came to exist and how it operated. The question of authority apparently being answered, Cornbury then looked for another way to shut the Council down.

His new idea was to require that all officers of the Council of Proprietors must swear an oath of allegiance. This seems reasonable until you realize that Quakers did not swear oaths, and the Council of West Jersey Proprietors was mostly made up of Quakers. So now Cornbury had an excuse to prohibit the Council from acting.4

Meanwhile–

Creation of Amwell Township

John Reading needed a town to live in, and it just so happens that in 1708, the Township of Amwell was created by royal patent. The choice of name was in recognition of the fact that John Reading was the most important person living in the area. There were other families there also, like the Holcombes and the Greens, but not many more.

The township of Amwell was not created by statute, as was normally done later on. Instead, a petition was brought to the Assembly for creation of a township, the Assembly and Governor’s Council approved it, and then sent it on to the Lords of Trade in England to be made official.

And this is what they got back, dated June 8, 1708:

From her majesty the Queen…GREETING Know ye that of our speshall grace our certain knowledge and mere motion have granted and by these presents do grant for us our heirs and successors to the men and inhabitants and their successors inhabiting above the uppermost bounds of that Tract of Land commonly known by the name of the thirty thousand ackers [that’s the Bowde Purchase] in the county of Burlington in the Western Division of our province of New Jersey on the eastern shore of Dellawar River . . . To be and remain a perpetual township or community in word and deed to be called and known by the name of the Township of Amwell.5

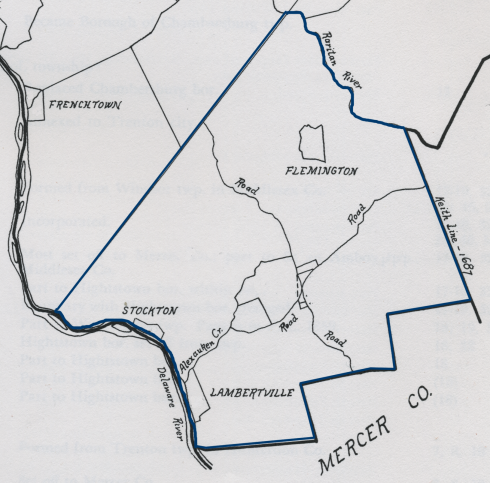

The new township was huge—far larger than most townships that then existed in Burlington County, excepting Hopewell. It contained all of today’s Delaware, Raritan, East and West Amwell, and parts of Readington and Lebanon. Soon afterwards, on September 28, 1708, the Grand Jury in Burlington levied a tax on all the municipalities in the county. Because of its very low population, Amwell paid the lowest tax, but it would not be long before Amwell was paying the highest tax, due to its rapid growth.

At the time, township officers were appointed by the Court rather than elected by residents. On September 13, 1709, the Burlington Court and Grand Jury passed a law directing assessors and collectors of the various towns to raise money to destroy wolves, panthers, crows, and blackbirds. This is the first time that Amwell Township officers were identified. They were John Reading Sr. and John Wilkinson as Assessors, and Samuel Green as Tax Collector.

On January 21, 1710 (new style), the Assembly passed a law that established the county boundaries throughout the colony. Burlington County’s new northern boundary was described as “the northernmost and uttermost bounds of the Township of Amwell.” That meant that everything north of that line was again in limbo, being designated as “unappropriated lands.” Which meant that that huge area purchased by Lewis Morris in 1709 was not part of any county. Not yet.

If Gov. Cornbury had a hand in this process, it was one of his last acts as governor. In March of 1708, thanks to some very terrible reports she had received, Queen Anne ordered that the Governor must return home and relinquish his position. His replacement, Gov. Lovelace, began his term in December.

Life After Cornbury

Once Cornbury was gone, the Council of Proprietors was revived. Lewis Morris became president, William Biddle was vice-president, Thomas Gardiner was surveyor-general, and John Reading was restored to the position of clerk & recorder. This should have meant that surveys could resume. But instead, in 1709, the Council decided that the Lotting Purchase should remain undivided until the rest of the Indian purchases were made. This was done in order to collect funds from the various proprietors to pay for the Indian purchases. But it took time to work this all out, especially since several of the proprietors lived in England and were hard to reach. Lewis Morris did not record his Indian Purchase until 1711.

Gov. Lovelace died suddenly in May 1709. He was replaced by Robert Hunter, although Hunter did not arrive in New Jersey until July 1710. He had a lot on his hands, being governor of two provinces. Settlement in the western reaches of New Jersey was not a high priority for him. He was far more concerned about managing his Council.

Gov. Hunter first met his Council in Burlington on December 6, 1710. He found nearly half of them were still loyal to disgraced Gov. Cornbury, and were determined to obstruct him however they could. So, in February 1711, Hunter petitioned the Lords of Trade in England to remove four of those members. Of course, one of the names on the list was Daniel Coxe.

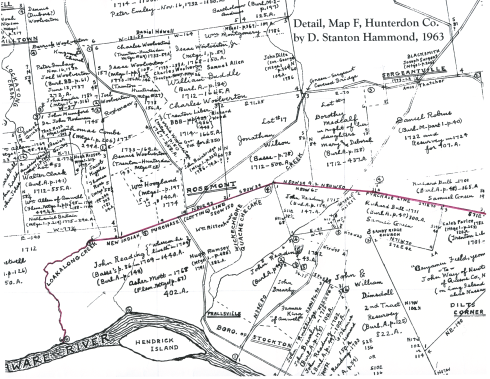

Returning to the question of surveys in the Indian Purchases, some surveys were being made in the years 1710-1711, but they could not be recorded until 1712, as can be seen in the map of proprietary tracts made by D. Stanton Hammond. Many of the tracts above the Lotting Purchase line (in red) were recorded in 1712 and 1714. The further north you go, the later the surveys, because the Council required that tracts being laid out had to be contiguous (although there appear to have been some exceptions to that rule).

Proprietors had been waiting a long time to get these surveys recorded. Once the dam broke, there was something of a land rush. The Surveyor’s office must have been swamped trying to get all the new surveys recorded. David Blackwell has observed that a lot of that land hunger was caused by the high demand for wheat from the urban areas of New York and Pennsylvania. There was a lot of money to be made in this land rush, and one of those most eager to take advantage of it was Daniel Coxe.

Daniel Coxe Takes Over

Daniel Coxe and his friends were unhappy with the distribution of land in the Lotting Purchase. They accused the Council of Proprietors of “dispotical” power for trying to regulate and record all the land purchases in West New Jersey, including their own.

Daniel Coxe and his friends were unhappy with the distribution of land in the Lotting Purchase. They accused the Council of Proprietors of “dispotical” power for trying to regulate and record all the land purchases in West New Jersey, including their own.

Now here is one of those events in history that leaves me scratching my head in bewilderment. Even though Cornbury was gone, and even though Gov. Hunter got Coxe removed from his Council, the West Jersey Council of Proprietors still felt so threatened by Coxe that they named him a member of the Council in 1712, and then elected him president! If that isn’t inviting the fox into the henhouse, I don’t know what is. (Apparently there were enough Coxe supporters on the Council to let this happen.)

One of the first things Coxe did as president was to fire John Reading as clerk of the Council, and choose the more accommodating John Wills in his place. Next, Coxe had the Council halt all surveying in the Indian purchases, and refuse to record any completed surveys. Thomas Gardiner, a Quaker, was forced to share the position of Surveyor-General with Coxe’s ally, Daniel Leeds.

The Coxe Council ordered John Reading, now the former clerk, to hand over the Indian deeds for the new purchase as well as all minutes, book and papers for the Council of Proprietors that he had in his possession. Obviously, these were papers accumulated after the fire of 1697. Reading was not eager to cooperate, and put it off as long as he could. But even though he did not like the make-up of the Council, he could not disagree that all of these records belonged in the hands of the Secretary of the Council, so eventually he complied. Then, oddly enough, some very large tracts of land were allotted to Coxe and his friends.

John Reading had been right to be suspicious. Later on, Gov. Hunter got evidence that Daniel Leeds had altered Council records. He was removed as Surveyor-General, and John Reading’s son John Reading Jr. was appointed in his place.

Back to the Governor’s Council. As mentioned earlier, in 1711, Gov. Hunter petitioned the Lords of Trade to remove about half of his council members for their opposition to his policies. On the list of recommended new members was John Reading, who was identified as “Proprietor and Clerk to the Proprietors.” Coxe and his supporters protested vehemently. Their case had to be heard by the Lords of Trade, which postponed taking action. Meanwhile, in October 1711, Gov. Hunter nominated John Reading to the Supreme Court of New Jersey.

When he didn’t get a response to his letter, he sent another one to the Lords of Trade in January 1712 in which he wrote that he was forced to “displace all the gentlemen of the Council” and to replace them with “others of known Integrity and Reputation.” Otherwise, everything would be “in danger of being determined more by Spirit of party than Rules of Justice.”

Gov. Hunter’s request was eventually granted by Queen Anne on July 20, 1712. But things moved very slowly back then; the Privy Council seems to have tabled the matter until 1713. John Reading did not take his oath as a member of the Governor’s Council at Burlington until December 7, 1713.

Next: Organizing to create a new county; action in the legislature; death of Mrs. Elizabeth Reading; John Reading’s last years.

Suggested Reading:

Several authors have given far more attention to this period in New Jersey history than I have done here. I recommend:

- Donald L. Kemmerer, Path to Freedom, the Struggle for Self-Government in Colonial New Jersey, 1703-1776. Princeton, 1940; Cos Cobb, CT: J.E. Edwards, 1968, 384 p.

- John Edwin Pomfret (1898- ), The Province of West New Jersey 1609-1702, A History of the Origins of an American Colony. NY: Octagon Books, 1976 (1956).

- John E. Pomfret, The New Jersey Proprietors and Their Lands. N.J. Historical Series, vol. 9. Princeton, NJ: D. Van Nostrand Co., Inc., 1964.

- John E. Pomfret, Colonial New Jersey, A History. NY: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1973

- Edwin Platt Tanner, The Province of New Jersey 1664-1738. New York, 1908.

Footnotes:

- Oscar M. Voorhees. The Exterior and Interior Bounds of Hunterdon County, New Jersey, Flemington, NJ: Hiram E. Deats, 1949, p. 6. ↩

- Portrait borrowed from Donald L. Kemmerer, Path to Freedom, opp. p. 47. ↩

- A very interesting biography of Cornbury was written by Patricia Bonomi, The Lord Cornbury Scandal; The Politics of Reputation in British America, Univ. of No. Carolina Press, 1998. ↩

- John E. Pomfret. Colonial New Jersey, A History, NY: Chas Scribner’s Sons, 1973, p.127. ↩

- Dr. Oscar M. Voorhees, “The Exterior and Interior Bounds of Hunterdon County.” Published in Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society, New Series, Vol. XI V, No. 3 (Newark: New Jersey Historical Society, 1929), 295-296. ↩

Sharon Moore Colquhoun

December 5, 2014 @ 8:41 am

Thanks for all the research and info. We were sorry to be miss your presentation and had hoped to attend.