This is the third and final part of a speech delivered on Nov. 16, 2014 for the Hunterdon County Tercentennial. You can find the first two installments here and here.

Petitioning for a New County

With so many surveys being made in the new Indian purchases, it was clear that people would be settling in this area very rapidly. And it was also clear that this new area was going to be hard to manage from far-away Burlington City. The residents of the northern townships in Burlington County were becoming frustrated by the need to travel 20 to 35 miles by horseback to the county seat to record their deeds, probate wills and attend court.1

A meeting was held in Maidenhead Township (now Lawrenceville) on January 1, 1712/1713, at which it was agreed to promote the creation of a new county “in the upper part of the Province,” and set up a fund to support the effort. Phillip Ringo was to collect the moneys. The top donor was John Bainbridge, who pledged £2,2 which earned him the privilege of appearing before the Governor on behalf of the town “in order for the accomplishment of the aforesaid business.”3 Although I have no record of this, it seems likely that the Governor advised Bainbridge to get up a petition and send it to the Assembly, for that is what happened.

There is no way to know when the petition was submitted, because from July 16, 1711 to December 7, 1713, the Assembly did not meet, and neither did the Council. This was a result of the ongoing conflict between Gov. Hunter and the Coxe faction. So although the petition was gathered in 1713, it was going nowhere until the legislature was able to resume their sessions. All this time, Gov. Hunter was waiting for his new Council members to be approved, among them, John Reading.

When the Council finally got back to work that December 1713, they took up the following bills: an act to regulate the killing of wolves, to raise money for jails and courthouses, to regulate the recording of deeds in each county and the practice of law, to allow Quakers to make affirmation rather than swear oaths, to prohibit the concealment of stray cattle or horses, and to regulate the making and mending of highways. They also passed a bill to prevent immorality (always a futile governmental gesture).4 Reading himself presented a Committee report on a bill to regulate Swine. After it passed, Reading was ordered “to carry the bill so amended to the house of Representatives for their concurrence.”

I am now going to move back and forth between the Assembly and the Council. On Dec. 17, 1713, a Petition was read in the Assembly from “the Inhabitants of Maidenhead, Hopewell and Amwell” asking for a new County in the upper parts of the western division of New Jersey. It was not quoted in the minutes, and I don’t think a copy of it was ever saved, so we do not know who signed it.

Consideration of the petition was put off to the following Tuesday, December 21st, when the petition was read again, and consideration was postponed for another two weeks. When the Council met in early January, Reading was absent, probably to spend time with his wife who was ill. He returned to the Council by January 8, 1714, and remained in Burlington meeting with Council for ten days, up until January 18th when he returned to Mount Amwell.

On January 15th, he appeared in the Assembly bringing with him an amended bill for shortening of law suits and regulating the practice of law, asking for the Assembly’s concurrence. The house then adjourned to 2:00 p.m. When they reassembled, Mr. Lambert, a member of the Assembly committee that had been considering the petition from the citizens of Maidenhead, Hopewell and Amwell, brought in a bill for erecting the upper parts of the Western Division of New Jersey Into a County. It was read and ordered a second reading next Wednesday. The bill got its second reading on January 20th, and was sent back to a new committee, consisting of Mr. Farmer, Mr. Kaighen and Mr. Sharp.

Meanwhile, John Reading had returned to his home in Amwell Township on January 18th. He was only just in time to be by his wife’s side when she died on January 20th. She was 57 years old, and they had been married for 32 years. His wife’s death must have been a devastating blow, made worse by the necessity of burying her in frozen ground.5

Despite his grief, two days later, Reading was back in Burlington meeting with the Council. Perhaps he needed the distraction, but he also had important work to do, for on that day, January 22nd, the new county bill as amended was brought back to the floor of the house. It passed and was ordered engrossed, or written out in fine copy. On January 23rd, the bill, now “engrossed,” was read and passed again. Mr. Fretwell and Mr. Lambert were ordered to deliver it to the Council, which they did on January 26th, at which time it got its first reading and was ordered for a second one, which took place on January 28th.

It was then “committed to the Gentlemen of the Councill or any five of them.” I assume that means it was sent to committee. It was not until February 11th that John Reading, as a member of that committee, returned the bill to the Council with several amendments. Unfortunately, we do not know what those amendments were. They were read and agreed to; then the bill was read a third time and passed.

Reading was instructed to carry the bill to the Assembly, which he did on February 12th. It passed and was ordered to be engrossed on parchment. A final note in the minutes of the Assembly dated February 15th stated that the bill was now “engrossed in parchment and composed in the house.” But the official date on the bill is March 11th, when the bill to create the county of Hunterdon was enacted into law. That must have been the day that the Governor signed it.6

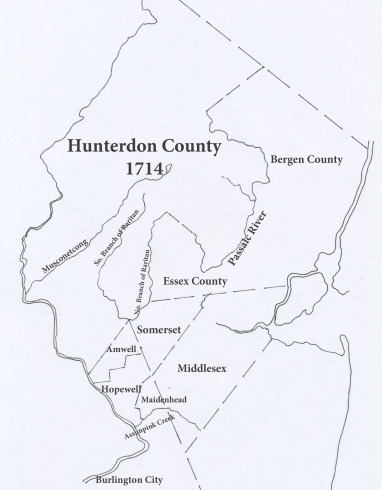

The language of the Act justified the need for a new county. Much of that language was probably taken from the original petition. It established its border with Burlington County along the Assunpink at Trenton. Everything north of that line, including Trenton, Maidenhead, Hopewell, Amwell and all points north within the former Province of West New Jersey became part of the new county.

An Act for Erecting the Upper Parts of the Western Division of New Jersey into a County

Whereas the Inhabitants of the upper parts of the said Western-Division, have, by their Petition set forth, That for many years last past their frequent attending the several Courts held in Burlington being at a very great distance from most of their Habitations, Inconvenient and troublesome, as well as chargeable to the Inhabitants of the said Upper parts of the Western-Division, aforesaid, and to the great Detriment and Damage of the said Inhabitants. For the Removing of which Inconviencys, and making of the said People more easie for the time to come, it is Humbly proposed and pray—that it may be Enacted.

And be it Enacted by the Governor, Council and General Assembly, and by the Authority of the same, That all and singular the Lands, and upper parts of the said Western-Division of the Province of New Jersey, lying northwards of or situate above the Brook or Rivolet, commonly called Assunpink, be erected into a County, and it is hereby Erected into a County, Named, and from henceforth to be called The County of Hunterdon; and the said Brook or Rivolet, commonly known and called by the Name of Assunpink, shall be the Boundry Line between the County of Burlington, and the said County of Hunterdon.

And be it Enacted by the authority aforesaid, That the said County of Hunterdon shall have and enjoy all the Jurisdictions Power, Rights, Liberties, Privileges and Immunities whatsoever, which any other County within the said Province of New Jersey doth, may or ought of Right to Enjoy, excepting only the choice of Members, to Represent the said County of Hunterdon in General Assembly, which liberty is hereby suspended until Her Majesties Pleasure be further known therein, or that it shall be otherwise ordered by Act of Assembly.

And be it further Enacted by the authority aforesaid, That until such time that the said County of Hunterdon shall be allowed the Priviledge of chusing Representatives of their own to serve in General Assembly, it shall and may be lawful to and for the Free-holders of the said County (being qualified according to law) from time to time, as occasion shall be to appear at Burlington, or elsewhere in the said County of Burlington, and there to vote and help to elect and chuse Representatives for the said County of Burlington, after the same manner as formerly, before the making of this Act, they were accustomed to do; and their said Votes shall be as good, and of the same validity and effect, as if the Person so Voting were properly Freeholders of the said County of Burlington, any Law, Custom usage to the contrary thereof not withstanding.

And be it Enacted by the authority aforesaid, That all Taxes and Arrearages of such taxes, that are already laid by Acts of General Assembly of this Province, which are all ready assessed or that are hereafter to be assessed, shall be assessed, collected, and paid according to the Directions of the said Acts formerly past for that purpose, and that all Persons concerned therein shall be under the same Restrictions and Penalties as are exprest in the said Acts, in all Intents, Constructions and purposes, as if this Act had never been past.

There is no way to know when the name of the county was chosen, but as it was part of the language of the Act, it may also have been part of the petition. There was only one possible name for this county—Hunterdon, after the popular governor who had made it possible. It was named after Gov. Hunter’s ancestral home, just as Amwell Township was named for John Reading’s.7 (Robert Hunter’s family came from Hunterston on the western coast of Scotland.)

The most populous, well-established town at this time was Trenton, so even though it was at the very southernmost location in the county, it was designated the county seat. And remained so until 1780 when the location was moved to Flemington.

As the Act declares, Hunterdon freeholders were not allowed to chose their own members of the Assembly. That would have to wait a few years. In fact, it was not until 1727, when the two representatives from the small town of Salem were allotted to Hunterdon.8 Four days after the Act became law, on March 15, 1714, as part of an act for the financial support of Her Majesty’s Government, John Reading Esq. and William Green were named assessors for Hunterdon County, and Ralph Hunt was named tax collector.9

In the 1720’s, New Jersey Governor William Burnet wrote that “the Division of West Jersey has spread so much in settlements to the northward that Brigadier Hunter found it necessary to . . . [create] a new County which is called Hunterdon and which is now as large and populous as any of the rest.” By the middle of the 18th century, Hunterdon County had the highest population of any county in the state of New Jersey.

On March 18, 1714, John Reading was named by Governor Hunter to be “Captain for the militia company of Amwell & the upper part of Hopewell, Hunterdon County,” and the next year, he was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel.10 That is how he came to be known as Col. John Reading, to distinguish him from his son John Reading Jr., who is usually called Gov. John Reading.

Queen Anne died on August 1, 1714. She was succeeded by the German-speaking Hanoverian, George I. Anne had originally been sympathetic to the Whig party in England, which meant she was well-disposed toward Gov. Hunter. But later on, she preferred the Tories. After her death, the Whigs came back to power and stayed there for many years. This was good news for Gov. Hunter, who once again had friends in high places, and he still had need of such friends.11

In 1716, Daniel Coxe (yes, he’s back) had taken control of the Assembly, through a combination of “Palbable Lyes” and a “Large dram bottle,” according to Gov. Hunter. The legislature was meeting in Perth Amboy that year because Hunter was afraid of attacks on the Quaker members if they met in (of all places) Burlington.12 Fortunately, by April, Hunter had managed to undermine Coxe’s powers, forcing him to leave New Jersey, to the relief of the Governor and a great many others.

Note: The relief was only temporary. Daniel Coxe would return to West Jersey around 1719 and wreak havoc in Hopewell Township in 1731, when he challenged the rights of the West Jersey Society to its Hopewell lands, and won—based on the failure of the society to record its deed from Daniel Coxe Sr. in 1692. The Society had been selling land there ever since, but Coxe was able to legally force those purchasers to repurchase the lands they had been living on for decades. But that is another story.

Col. John Reading had been present at the 1716 session in Perth Amboy, which meant a long ride across New Jersey in the dead of winter. He was present again on June 1st when Council members asked the Governor to let them recess until after the corn and hay had been harvested, and seed time had passed. The request was granted and the next meeting was held on November 27, 1716; but not at Burlington—small pox was prevalent there. The Council had to meet at Chesterfield while the Assembly met at Crosswicks.13 This meant more long distance travel for John Reading, who was now 57 years old.

The Council met through December and January, but when next they met at Perth Amboy, in May 1717, Reading was absent. He missed some excitement, for at that meeting, Gov. Hunter’s remaining opponents presented a petition demanding that he be removed from office. The Council dealt with this insubordination by adjourning until April 9, 1718.

At that time, Gov. Hunter nominated four new members to the Council, two for the eastern division and two for the western division, because of the absence or death “of several of the Gentlemen of Council.” One of these gentlemen was John Reading Esq., who had died at Mount Amwell on October 30, 1717 at the age of 61.

He had led a full and active life, and was instrumental in the creation not only of a township, but of an entire new county. He did not do this on his own, of course, but because of his efforts, he can legitimately be called Hunterdon County’s founding father.

Footnotes:

- Detail of map by John P. Snyder in The Story of New Jersey’s Civil Boundaries 1606-1968, Trenton, 1969, p. 35, “New Jersey 1714-1715.” ↩

- “Dawn of Hunterdon,” p. 12 of The First 275 Years of Hunterdon County. ↩

- Published in NJHS Proceedings 3rd ser., vol. 6 (1909-10), no. 3 (1908) p. 152. ↩

- NJ Colonial Documents, first ser., vol. 13, Journal of Governor and Council, vol. 1, pp. 492, 497-502. ↩

- The graves of John & Elizabeth Reading are probably at Mount Amwell, but their location is not known. There is a family tradition stating that they were buried at the Buckingham Friends Cemetery near Centre Bridge, PA. But if that was so, those graves are also gone. ↩

- NJCD, first ser., vol. 13, Journal of Governor and Council, vol. 1, pp. 505, 507, 512-13. New Jersey Archives, 3d series, vol. 2, Laws of the Royal Colony of New Jersey, 1703-1745, p. 166. The text of the legislation is also reprinted in Wittwer, The First 300 Years of Hunterdon County, pp. 12-13. ↩

- Wittwer, p.12. ↩

- Voorhees, p. 8. New Jersey Archives, 3d series, vol. 2, Laws of the Royal Colony of New Jersey, 1703-1745, p. 387. ↩

- New Jersey Archives, 3d series, vol. 2, Laws of the Royal Colony of New Jersey, 1703-1745, p. 119. ↩

- NJ State Archives, MSS Commissions, Book AAA pp. 158, 169. ↩

- Kemmerer, p. 98. ↩

- Kemmerer, p. 101. ↩

- Samuel Smith. The History of the Colony of Nova-Caesaria or New Jersey, Burlington, 1765, p. 408. ↩

Glenn R. Smith

December 14, 2014 @ 12:20 pm

enjoyed reading your articles about the creation of Hunterdon County. I have a 5x grandfather, Robert Smith, who lived in Asbury/Bethlehem Twp. around 1750 so many of these names are familiar to me.

thank you