In her excellent book All Roads Lead to Pittstown (2015),1 Stephanie Stevens called attention to the early roads that converged on the village of Pittstown. Roads were certainly important, but just as important were creeks in creating the locations of Hunterdon villages.

In the 18th century, there were very few power sources. It was basically wood (a lot of it) and water. The water powered sawmills for shaping lumber into wood for building, grain mills to turn wheat into flour, and fulling mills to clean and prepare wool for spinning into yarn.2

It was the fulling mill of Edward Rockhill that gave Pittstown its start.

But before Rockhill, there were the West Jersey proprietors. And before them there were the Lenape. To write the history of the Pittstown Inn requires a dip into New Jersey’s early history, and to the earliest years of Hunterdon County’s existence.

The First Owners

Turning Land into a Commodity

The Lenape people were certainly familiar with the Pittstown neighborhood—familiar enough to give a name to the creek that runs through it, a name it still has: the Capoolong. I often wonder how strange the concept of land ownership must have seemed to the Lenape people, and, even more so to exchange ownership for commodities, like silver and gold.3

As discussed in my articles on the earliest years of Hunterdon County, settlement began with huge purchases of land from the native Lenape people by the proprietors of West New Jersey, who were then living in Burlington County. The first one took place in 1703 when John Reading bought 150,000 acres. (For more on the first purchases, see John Reading, Part One and Part Two. Part Two includes a list of all my articles on 17th century land ownership.)

This was followed in 1709 by a 100,000-acre purchase by Lewis Morris (pictured left), located just north of the Lotting Purchase. That was followed by the creation of new boundaries for Burlington County. In my article, “John Reading part one,” I wrote:

On January 21, 1710 (new style), the Assembly passed a law that established the county boundaries throughout the colony. Burlington County’s new northern boundary was described as “the northernmost and uttermost bounds of the Township of Amwell.” That meant that everything north of that line was again in limbo, being designated as “unappropriated lands.” Which meant that that huge area purchased by Lewis Morris in 1709 was not part of any county. Not yet.

Morris did not record his Indian purchase until 1711, after becoming president of the Council of Proprietors. That must have prompted him to hand off his Great Tract to an association of land-hungry speculators calling themselves the West Jersey Society. The Society immediately began dividing the tract into smaller parcels and sending surveyors into the wilderness to lay out the boundaries.4

Most of the deeds I research were recorded long after the first purchases were made, and in the deeds the boundaries are indicated by properties belonging to bordering owners. But in 1711 there were no bordering owners, so boundaries were designated as running from one natural (and rather impermanent) landmark to another: for instance, from a big rock to a maple tree. Apparently, these features were recognizable to the early surveyors, who were extremely hardy fellows. They undoubtedly depended on Indian paths to find their way through the wilderness. As mentioned in the book, A History of East Amwell, 1700-1800 (p.5), Indian paths were just wide enough for one person walking. The Indians had no horses, but the new settlers did, and the increased travel turned those paths into roads. In her book, All Roads Lead to Pittstown, Stephanie Stevens describes the two most important of those Indian paths that converged on Pittstown, known today as Routes 513 and 579.

As for the earliest surveys, one of the first was made for Amos Strettle, on March 19, 1711.5 It was for 5,000 acres located “above the Falls of the Delaware River, in Bethlehem Township.” (There was no Bethlehem Township in 1711—this description came from a later deed.) At the time, Strettle was living in Dublin, Ireland. Apparently, he had an agent in the Province who handled the paperwork.

Strettle had no interest in actually living on the tract, or even of making the trip to New Jersey. Ten years later, on November 3, 1721, he conveyed the 5,000 acres to his brother Abel Strettle, and ten years after that, on November 12, 1731, Abel Strettle, who also remained in Ireland, conveyed a portion (438 acres) to Edward Rockhill, Jr. of Chesterfield, Burlington County, by means of Strettle’s Burlington, NJ attorney, James Hatton.6

EDWARD ROCKHILL

In 1988, Ursula Brecknell wrote a short history of Pittstown as part of the application for historic district status. She did an admirable job of focusing the village history on its status as an “early crossroads trading center,” then as “a revenue-producing gentleman’s estate,” and in the mid-19th century, as “a locally important rural center for industry, agriculture, commerce, and railroad transportation.”

Ms. Brecknell identified the village as “founded as Hoff’s Mills in the 1740s,” but the mills belonged to Edward Rockhill before Charles Hoff came along. She stated that Rockhill was an absentee owner, and that Hoff was his tenant and “a pioneer settler.” But Rockhill was in fact himself a pioneer settler. It is true, he was living in Chesterfield in the early 1730s when he purchased the Hunterdon properties, but he did move to the county soon afterwards.

Rockhill was a resident of Chesterfield County when he purchased the site and moved to Hunterdon afterwards. Hoff was a “pioneer settler,” as Brecknell wrote, but one could say that Rockhill was also. He was a freeholder in Hunterdon as early as 1739, and according to Hubert G. Schmidt in his book Rural Hunterdon (p.212), Rockhill was present in the Pittstown area in the 1730s when he built the first grist mill in the area.

A reader of these Pittstown articles, Geoff Rockhill, who has done a lot of research on his family, provided me with new information which I am incorporating here.

Sometime before March 3, 1683, Edward Rockhill of Adlingfleet, County of York, England was married in the parish of Broughton, England, to Mary the only daughter of Robert Richardson, late of Wooton in the county of Lincolnshire. Robert Richardson had written his will on Jan. 27, 1679 leaving £100 to daughter Mary, which was being transferred to Edward. Also, Robert’s house in Adingfleet “now in the tenure of Edward Rockhill” was being transferred to his “beloved friend Joseph Richardson of Stamfordbridge” and Thomas Naimby. (Unfortunately, because the contract is so hard to read, I cannot be certain that it was Robert Richardson who was signing it.)

This contract makes me suspect that Edward & Mary had been living in her father’s house until his death at which time they moved to West New Jersey. This was Edward Rockhill, Sr., who was active in the Quaker community in Chesterfield, and in the 1690s was one of the trustees of the Quaker meeting there. He was among those purchasing a lot for a Quaker meeting house in 1693. In deeds of that period, he was identified as a yeoman, but in the deed of 1697, he was identified as a ropemaker.

On Jan. 4, 1724, Edward Jr. married Ann Clayton (1707-1767) in Chesterfield County. The couple had four children: three daughters and one son, the son being Dr. John Rockhill, whose bible is a primary source for Rockhill genealogists.7

In 1735, Edward Rockhill bought a second large tract from Abel Strettle and his attorney Thomas Hatton, being 408 acres, which Rockhill mortgaged.8 The mortgage stated that the property was located in Bethlehem Township. It bordered another brook, known today as the Lockatong, but back then as the Laokolong Brook. It was further south than the 438 acres, close to today’s Route 12. In 1745, Rockwell sold the 408 acres, which was described as timber swamp in Kingwood Township, to Achsah Lambert. (Kingwood Township was created out of Bethlehem probably about that time.) When Lambert wrote her will about 1790, she bequeathed the 408 acres to her niece, Elizabeth Cadwallader, who sold it in 1792 to Jeremiah King.9

It is remarkable how quickly settlement of Bethlehem Township took place. The township was created about 1730. (Record-keeping at that early date is less than ideal.) The County of Hunterdon had been in existence since 1714, so by the 1730s, the system of county government, relying on freeholders elected in the townships, was fairly well-established. Edward Rockhill took an active part in his community and in 1739 he was serving as a County Freeholder.10 In 1746 he was a Justice of the Peace.

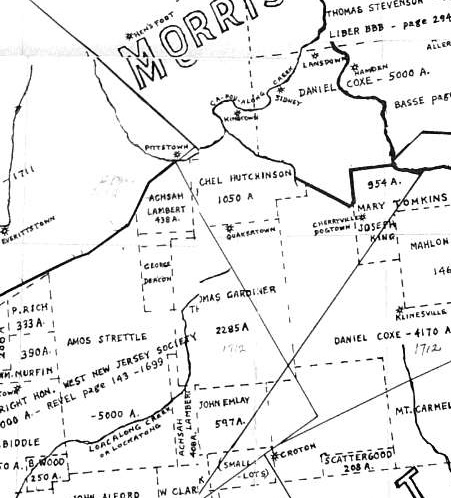

According to the Hammond Map for the Pittstown area, Rockwell’s first purchase, the 438 acres which covers the Capoolong Creek, was also sold to Achsah Lambert.11 Hammond’s mapping standard was to write the earliest known owners of the first properties, and that can be misleading. In the case of Achsah Lambert, it would seem that the sale of 438 acres did not go through, because soon afterwards, Rockhill was selling part of the same property to someone else, i.e., Charles Hoff.

On June 16, 1747, Edward Rockhill, yeoman of Bethlehem Township, & wife Ann conveyed to Charles Hoff Jr. of Amwell, shopkeeper, a tract of 204 acres, “whereof the said Charles Hoff is in actual possession,” bordering the Society’s line, other land of said Rockhill, and Samuel Stevenson, being part of a tract of 438 acres that Rockhill bought from Abel Strettle.12 This does confirm Ms. Brecknell’s observation that Charles Hoff was present in Pittstown in the 1740s. But his residence, according to the deed of 1747, was Amwell Township, located to south of Bethlehem Township.

Rockhill did not sell all of the 438 acres to Charles Hoff. After his death, his executors sold a tract of 174.5 acres to Thomas Little, who established a sawmill on the Capoolong, and whose property, a short distance south of Pittstown, came to be known as Littletown.13 Ms. Brecknell noted that Charles Hoff owned a complex “a few miles south of his mills,” with a forge “for refining pig metal into bar iron.” Was this at Little Town? Or further south on the 408 acres?

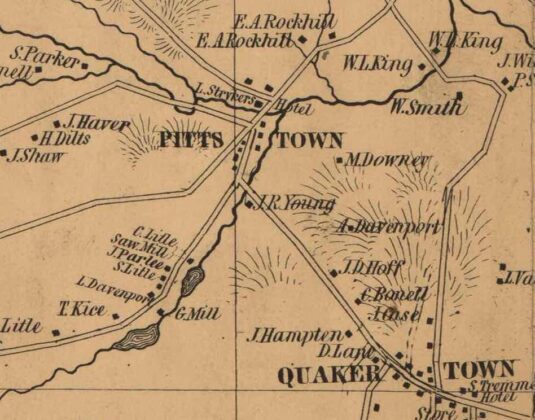

Below, detail from the 1851 Cornell Map, showing the group of mills a short distance south of the village of Pittstown.

The Rockhill Estate

On June 6, 1748, Edward Rockhill wrote his last will & testament. He identified himself as “of Amwell Township,” so he had by then moved away from his Pittstown property, leaving it in the hands of Charles Hoff, Jr. In his will he named his wife Ann, his daughter Mary and her husband William Godley, his son John, his “negro boy Dick,” and daughters Ann & Achsah. He named wife Ann his executor along with “brothers” (i.e., brothers-in-law) Parnall Clayton of Burlington County and William Clayton of Trenton.

Rockhill must have died immediately after writing the will, because the inventory of his estate was taken the next day, June 7, 1748. “Negro boy Dick” was valued at £30. There was also “negro boy Peter” who was valued at £28. Also included in the extensive inventory was the fulling mill and 50 acres of land, valued at £124. The will and inventory were recorded on June 10, 1748.

Almost two years later, on February 1, 1750, Ann Rockhill and William Clayton, acting as executors of Rockhill’s estate, sold that fulling mill and its 50 acres to Charles Hoff.14

Ann Clayton Rockhill married her second husband, one Richard Salter, about 1755 who wrote his will on January 11, 1762, when he was living in Burlington County, leaving £100 to his unnamed wife (Ann), along with all the goods that were hers before their marriage. Ann wrote her own will on August 10, 1767, when she was living in Trenton. She left a tract of 50 acres to her son John Rockhill, “which he now has,” but did not say where it was located. She also noted that she had “given directions to Achsah Lambert to distribute my other goods.” She died not long afterward, at the age of 60.

CHARLES HOFF, Jr.

Charles Hoff, Jr. (c.1720-1782) was the son & eldest child of Charles Dirksen Hoff and Angelica Johnson of Hopewell Township. Charles married his first wife, Mary, about 1742 (based on the age of their eldest child; I have not found a marriage license or other record). The couple had seven children, two or three of whom died young. Eldest child, Catherine married Isaac FitzRandolph, who will appear later in this story.

In 1755 when Charles Hoff, Sr. wrote his will, he left only £10 to son Charles Jr., and his home plantation in Hopewell to son Cornelius, strongly suggesting that Charles Jr. was well-established on his own by that time.

Hammond’s Mysteries

As my readers know, I am heavily dependent on the remarkable maps created by D. Stanton Hammond of the earliest land purchases in Hunterdon County. Which is why I cannot ignore (but am extremely puzzled by) what he shows for the Pittstown area. There are two mysteries.

First is a notation on his Index Map that covers Pittstown as well as the Strettle tract, which reads: “The Right Hon West New Jersey Society, 22,000 A. – Revel, page 143 – 1699.” This was taken from a survey book, but 1699 is way too early for properties in this part of the County, and I have not done the research that would turn up an explanation. (Detail of Hammond’s Index Map, below.)

The second mystery is on Map D, which gives a more detailed version of early landowners. It shows Pittstown covered by “Bonnell & Hoff’s-500 A. The Exception in the Society’s Deed (NJA Vol. K p.219) 1752.” I have not been able to examine the deed that Hammond recited, but it makes no sense to me, given that the property had been conveyed to Hoff in 1747. Perhaps the Society was surveying its remaining property as of 1752 and made exceptions for properties that had already been sold. However, Abraham Bonnell, another early Hunterdon settler, never associated with Charles Hoff for real estate investments, as far as I can tell. If he did, the two of them never left a record of it.15

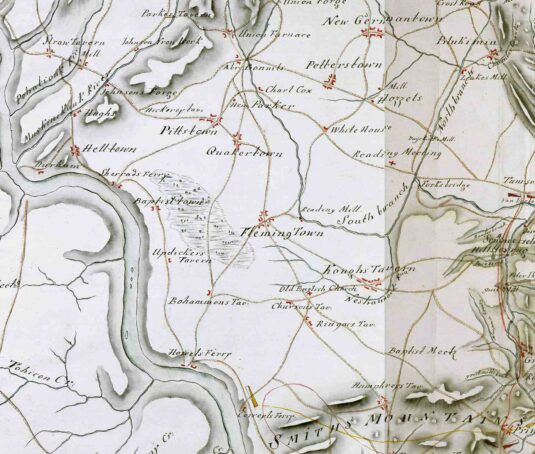

Hoff Town

As you can see from the map on the left, the village that developed at the crossroads close to the Capoolong Creek acquired the name Hoff Town, reflecting the huge acreage owned there by Charles Hoff. The name was still being used in 1778 when this map (known as the Fadden Map) was made. No doubt it inspired Stephanie Stevens to name her book All Roads Lead to Pittstown.

As you can see from the map on the left, the village that developed at the crossroads close to the Capoolong Creek acquired the name Hoff Town, reflecting the huge acreage owned there by Charles Hoff. The name was still being used in 1778 when this map (known as the Fadden Map) was made. No doubt it inspired Stephanie Stevens to name her book All Roads Lead to Pittstown.

Along with his mills, Hoff established a tavern, possibly on the 50 acres that he purchased in 1750 from the widow Rockhill. It was probably in operation as early as 1754 when lottery tickets were offered for sale at various locations in Connecticut and New Jersey to benefit the College of New Jersey. On the list was “Mr. Charles Hoff, junior, in Kingwood.” Ms. Brecknell assumed that this was a tavern rather than a private house. She was probably right, but it shows how little evidence researchers have for 18th century events.

Hoff was important to his community, just as Rockhill was. He was identified as a trustee of the Kingwood Presbyterian Church in a deed of 1754, when a lot was purchased in Kingwood for the location of a church building. In 1756 he was identified as a Justice of the Peace. That same year he was named executor of the estate of William Allen of Bethlehem, and in 1762 administered the estate of Cornelius Farrill.

On July 6, 1762, Hoff purchased a property of 259 acres in Kingwood Township from William & Elizabeth Wright of PA.16 This turned out to be a mistake. Only one month later, as he was forced to offer all his properties for sale.

1762 a year of changes

Hoff was often identified as a merchant, running a store in Pittstown, but the store, the mills, a forge and a tavern did not produce enough income to match his expenses. His situation must have been pretty dire to force him to submit an advertisement to the Pennsylvania Gazette offering all of his properties for sale. It was published on August 12, 1762.

The list is such an impressive one, I am including all of it, as it serves as an inventory of Hoff’s properties and his operations in the village and surrounding areas.

“To be sold by the Subscriber, living in Kingwood, in the County of Hunterdon, and Province of New Jersey, the following Premises: One over-shot Stone Grist-mill, with about 100 Acres of Land; a Stone Dwelling house, with a Frame House adjoining, and Buildings convenient for keeping Store, so as to front between 60 and 70 Feet, at which Place a Store hath been kept for upwards of 20 Years past; two bearing Orchards, the one grafted Fruit; about 10 Acres of Meadow, a Frame Barn, Stables &c. this Mill chiefly employed in grinding Grists, having a very great Run of Country Custom. Also one Breast Grist-mill, chiefly kept for Merchants Work, at which a considerable Quantity of Flour is made yearly; a Saw-mill, for accommodating the Works with Boards, Stuff, &c. with 100 Acres of Land; a Stone Dwelling-house and two Log-houses; 15 Acres of Meadow and a Quantity of Swamp for making more Meadow; with a well frequented Stone Tavern and Stone Kitchen, the house affording five Rooms and a Cellar; the said Tavern in in the Cross-roads, leading from Trenton and New Brunswick to the Forks of Delaware [my emphasis], &c: a Well of good water at the Door, and a very good Spring not above 60 Paces distant: The Tavern, with some Meadow, and about 30 Acres of Land (15 whereof Woodland) may be sold separate.

Likewise, to be sold a Fulling-mill and Stone Dwelling-house, with about 30 Acres of Land, about 4 Acres thereof Meadow. Also, a plantation of about 70 Acres of Land, a Stone House and Log Addition, a young Orchard, and about 8 Acres of Meadow before the Door, with a good Spring near the House.

And a Plantation of about 60 or 70 Acres, a square Log-house, a Good Spring at the Door, and Spring-house, with some Meadow and some Woodland. Likewise, about 60 Acres of Wood-land to be sold.

The Subscriber has also for Sale a Forge with two Fires for refining Pig Metal into Bar-Iron, with 70 or 100 Acres of Land, together with a Coal House, and other Houses for accommodating Workmen, being capable of making about 50 Tons of Bar Iron yearly: The said Forge lies very convenient to a Tract of Land called the Great Swamp, from whence it hath been supplied with a considerable Quantity of Coal-wood Gratis, and more is offered on the same Terms.

A Part of the aforesaid Premises being under Rent for near £200 per Annum, and the rest, at a moderate Computation, might be rented at £125 per annum. The reason of its being divided into parcels is to accommodate purchasers, as it was thought it might be a heavy Purchase for one Person; but if any such Purchaser should present, it may all be sold together. The whole pleasantly situated in a little Country Village, convenient to Places of Worship of three different Denominations, viz Church, Presbyterians, and Quakers, the farthest not exceeding three Miles. The Terms of Sale will be, the Purchaser or Purchasers to pay Half down at entering on the Premises, and the Remainder in reasonable Payments. A sufficient Warrant and Deed will be made, on paying the one Half of the Purchase Money, and giving Security for the Remainder, by me, Charles Hoff, jun.17

That “little Country Village” was Hoff Town.

In 1764, Hoff managed to sell a small portion of his properties, being a lot of 34 acres which was separated out of the Wright purchase and conveyed to Benjamin Coddington.18 But the rest did not get sold so the creditors took Hoff to court. and in 1764, the property was seized by the county sheriff, “in Execution (subject to Mortgages) at the suit of John Mease, Ann Pidgeon, Andrew Reed, and Charles Pettit.”19

The County Sheriff held a sale at Hoff’s Kingwood house but still no one bid high enough. The offer was made again on February 21, 1765,20 and another sale held on April 3, 1765.21 And still no buyers—with one exception:

ISAAC FITZRANDOLPH

As mentioned earlier, Charles and Mary Hoff’s eldest child, Catharine, married a man named Isaac FitzRandolph (c.1740-1768), probably about 1760. I have not found evidence of this but would not be surprised to learn that FitzRandolph had been acting as Hoff’s tavernkeeper prior to his marriage with Hoff’s daughter. The couple resided in the tavern house where they started their family of three children.

When Hoff found it necessary to sell all his properties in 1762, it appears that Fitzrandolph bought the tavern lot. According to Charles S. Boyer,22 FitzRandolph obtained a tavern license about this time, which stated that “sd place hath for a number of years past been Licensed.” Those earlier tavern licenses are not available. But this reinforces the idea that the tavern was in operation by the early 1750s.

Unfortunately, if FitzRandolph had plans for enjoying life as a tavernkeeper, they were foiled. He died very young, perhaps no more than 28 years old, most likely from a fatal accident. However, he had time to write a will, probably in 1768 (the will was not dated), in which he identified himself as “Isaac Fitz Randolph of Kingwood, sadler,” suggesting the tavern was a business on the side. He ordered his executors, i.e., his wife Catherine, father-in-law Charles Hoff, and father Jacob FitzRandolph, to sell his movables to cover his debts, and if that was insufficient, to sell the tavern lot and two acres. The will was recorded on October 31, 1768. His widow remained in the tavern house. A mortgage of 1772 identified “Widow FitzRandolph’s Tavern lot” as bordering Pittstown property (more on that later).

Last Words on Charles Hoff

On March 13, 1766, sale of the Hoff property was advertised for the coming April 15th being:

That Valuable Estate in Kingwood, H.C., NJ, late the Property of Charles Hoff, Esq. Lists 1) Mansion House with 97 acres and overshot grist-mill; 2) New Stone House, grist mill, saw mill and 36 acres; 3) House with 67 acres; 4) Stone House, fulling mill, Dye House on 15 acres; 5) Woodlot of 22 acres, all about 30 miles from Trenton. “Attendance will be given by Joseph Reed, Thomas Wharton, and Moore Furman.” Vendue on the Premises.23

Those three men giving “attendance” were commissioners who had been named by the court to manage the sale. Moore Furman paid special attention to this matter (see below).

Hoff seems to have downsized his residence while attempting to sell his huge acreage. On June 9, 1768, he purchased a “corner house & acre” at a sheriff’s sale from defendants John & Henry Farnsworth. (This was not the tavern lot.) Two years later he sold that lot to John Emley,24 and was obliged to support himself by means of a pedlar’s license, which was granted to him in 1771.25

Despite his financial hardships, that same year, he served as a surety for his brother Gabriel Hoff, tavernkeeper of Kingwood, along with Daniel Pegg.26 From 1778 until his death, Charles Hoff was not taxed in Kingwood, or anywhere else in Hunterdon County, indicating that he owned no real estate during those years.27

There is a generally accepted death date for Charles Hoff of December 22, 1782, age 62, while the Revolution was still in progress. His first wife Mary had died in Amwell Twp. on August 12, 1761, and his second wife Abigail died on August 19, 1772. (I do not have a source for these dates, and apparently the grave locations are unknown.) Perhaps it was this sad come-down that encouraged the next owner of Hoff’s property to change the name of the village to something more inspiring.

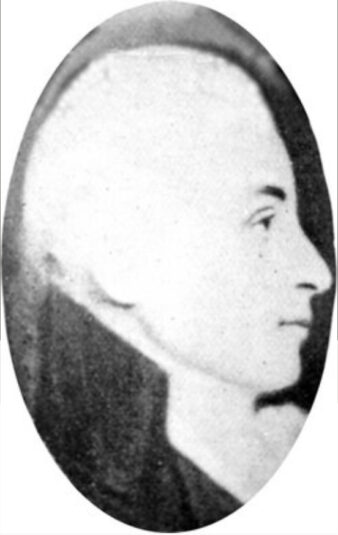

MOORE FURMAN, ESQ.

Why is it so hard to identify Moore Furman’s parents? Ms. Brecknell names Jonathan Furman of Hopewell as his father. If that was the case, then Frances Lanning was probably his mother. There is just one problem. When Jonathan Furman wrote his will on Sept. 14, 1771, he named his children Richard, Daniel, Joshua, Elizabeth Bills [Biles?], Sarah Furman and Mary Furman. No Moore Furman. Could Moore have been estranged from his birth family?

Another possibility is that he was the brother of the Josiah Furman of Trenton who purchased a 40-acre parcel from the executors of Richard Salter, dec’d, husband of Ann Clayton Rockhill. Josiah Furman was a merchant at Pennington, but after his store burned down, he moved across the river from Coryell’s Ferry (Lambertville), and called the settlement there New Hope. His wife was Deborah Ringo, who died in January 1830 in Bethlehem Township, age 90.28

In her history of the village of Pittstown, Ms. Brecknell noted that one of Charles Hoff’s creditors, Andrew Reed, was a business partner of Moore Furman, who was a very successful Trenton businessman. He had served as Hunterdon County Sheriff in 1757. In the 1760s, Furman moved to Philadelphia and went into the importing business with William Coxe and son Tench Coxe and became even more prosperous. While there, he married Sarah White (1743-1796), member of a prominent Philadelphia family.

In her history of the village of Pittstown, Ms. Brecknell noted that one of Charles Hoff’s creditors, Andrew Reed, was a business partner of Moore Furman, who was a very successful Trenton businessman. He had served as Hunterdon County Sheriff in 1757. In the 1760s, Furman moved to Philadelphia and went into the importing business with William Coxe and son Tench Coxe and became even more prosperous. While there, he married Sarah White (1743-1796), member of a prominent Philadelphia family.

Pittstown’s Name

One cannot write about Pittstown and its tavern without taking note of the Stamp Act Crisis of 1765, in which American merchants were required to import their goods only from Great Britain. This prompted a boycott of English goods, and it is believed that Moore Furman took an active part in protesting this measure. There was anger in Hunterdon County also. Ms. Brecknell mentioned a meeting of the Sons of Liberty that took place in Ringoes in March 1766. Representatives from each township were chosen to attend, including Dr. John Rockhill, son of Edward Rockhill, and as Ms. Brecknell wrote, “a friend of Furman and a neighbor to his Pittstown properties.”

Relief came from the intervention of William Pitt the Elder, member of the British Parliament, who was active in 1766 in bringing about repeal of the hated Act. Celebrations were widespread, with multiple toasts to Mr. Pitt, the “eminent friend of Freedom.”

Just when did Moore Furman acquire the Hoff properties in Kingwood and Bethlehem Townships? Even Ms. Brecknell with her admirable researching skills was unable to pin down a date, writing that “precisely when or through what steps Furman acquired the Hoff properties remains unclear.”

Recall that Furman acted as a real estate commissioner in March 1766, the same month that the Sons of Liberty were meeting, and most likely bought up pieces of the Hoff estate soon afterwards. Finding himself in possession of a whole village, Furman was able to express his gratitude to William Pitt by changing the town’s name from Hoff Town to Pitts Town. The new name was certainly in effect before June 1768 when Jacob Gooding gave notice in the New York Gazette of June 16th that his servant man, John Ryan, had run away. Anyone who caught him, should return him “to Jacob Gooding at Pitts-Town (formerly called Hoffs Town) or to Moore Furman in Philadelphia.”29

The best document for Furman’s ownership of the village is a mortgage dated April 2, 1772,30 in which Furman mortgaged “diverse messuages, mills & parcels of land” to Thomas Hookley of Antigua for £1300. Included was a property in Kingwood Township bordering the Capoolong Creek, John Rockhill, the Widow Little, Charles Hoff, Esq. and “Widow Fitzrandolph’s tavern lot,” among others.

Researchers have given Catherine Hoff FitzRandolph a death date of August 18, 1779, but that seems to be a different Catherine Hoff. We do not know exactly when Mrs. FitzRandolph died, or exactly when the tavern lot was conveyed to Moore Furman, but it must have been some time in the 1770s.

Bethlehem Divided

About ten years before the outbreak of the Revolution, Bethlehem Township was divided into two separate municipalities, one of them retaining the name Bethlehem, the other being named Alexandria Township after James Alexander (1691-1756) who served as NJ Attorney General in 1744 and owned large tracts of land in the Province of West New Jersey.

This new municipality included part of the village of Pittstown, but Kingwood Twp. also laid claim to the village. Ms. Brecknell noted that in 1778 Kingwood Township included Pittstown. She wrote:

The 1778 rateables for Kingwood Township (which included Pittstown in that period) list Furman with 653 acres taxable and describe him as a merchant. Again, listing him as a merchant, the 1779 rateables imposed a tax on the same 653 acres but also a sawmill and fulling mill “formerly his father’s,” and three gristmills; also 20 horned cattle, 12 horses, and 12 hogs.” One of these grist mills (Bodine’s Lumber) was built at this time for the Army Commissary, according to historian Snell.

I am puzzled by that statement that the fulling mill was ‘formerly his [Furman’s] father’s and can offer no explanation.

Moore Furman & the Revolution

In 1778, Furman was named Deputy Quartermaster-General for New Jersey. Again, I must rely on Ms. Brecknell’s work—in this case, her admirable description of Furman’s participation in the Revolution:

In 1779, he removed his headquarters to Pittstown, possibly considering the farms north of Hunterdon County a better source of supplies. It was also closer to Washington’s headquarters, which at that time (December 3, 1778 – June 3, 1779) were at Camp Middlebrook in the Watchung Mountains of Somerset County overlooking the Raritan River. Records of his frustrations in having insufficient funds to buy forage and grains at skyrocketing prices, and difficulty even in finding sellers, are contained in his letters to fellow officers. Cartmen were abandoning their work because they said they could not live on the pay.

Nonetheless, he rounded up and sent what he could, including hundreds of horses to be put to various uses, and huge quantities of board lumber which he shipped to Raritan Landing. He resigned in 1780, stating he was “obliged now for the support of my family to remove to my farm at Pitts-Town.” During this period, while resident at Pittstown, Furman served as judge of the Court of Common Pleas (1777-85) and Justice of the Peace (1781 and 1786) and filled other important governmental appointments.

I don’t often write about the Revolution in New Jersey, but now that the subject has come up, I cannot neglect the opportunity to post my favorite Revolutionary War era map, one composed by Hessian soldiers who had come to fight on the side of Great Britain. It shows again how Pittstown was located at an important intersection, and it certainly is a beauty!

Ms. Brecknell’s description of life in Pittstown during the Revolution is quite vivid. Considering the kinds of traffic that came to the village during those years, one must also envision those old country roads, especially Route 579, accommodating crowds of men on horseback. Ms. Brecknell continues:

During Furman’s ownership of Pittstown, the tavern continued to be operated in the charge of various innkeepers, while it served as a center for venues of great tracts of land (including those owned by Lord Stirling, James Alexander), for inquisitions of Loyalists, and for a court hearing by magistrates and Army officers on petition of residents of three townships who had failed to serve their time in the local militia, or to find substitutes. In November 1776, the New Jersey legislature, in flight from other locations because of the British threat, met in Pittstown. An announcement in the New York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, January 27, 1777, stated that Governor William Livingston had scheduled a meeting with the Assembly in the village. The New Jersey Council of Safety convened in Pittstown on October 16, 1777, and remained in session there until the 24th, guarded by a detachment of soldiers. In December 1778, British soldiers captured with General Burgoyne’s Army were briefly kept in the village before being marched to Virginia. These events may explain a tradition recited by historian Snell (1881) that a part of the American army was once encamped at Pittstown.

As mentioned earlier, 18th century records are not very helpful. I cannot say exactly who Moore Furman relied on to run his tavern during the Revolution and the years immediately afterward.

In April of 1782, peace talks commenced in Paris. By that time, the pressure on Furman to supply the army had been relieved. But it took until February of 1783 for Britain to declare an end to hostilities, and the final Treaty of Paris was not signed until September of that year. Imagine what it must have been like waiting weeks to get news of what was happening.

There is much more to the history of the Pittstown Inn, but it will have to wait until Part Two gets published.

Footnotes:

- I reviewed it here: The Pittstown Roads. ↩

- Here is Wikipedia’s definition of a fulling mill: “Fulling, also known as tucking or walking (Scots: waukin, hence often spelled waulking in Scottish English), is a step in woollen clothmaking which involves the cleansing of cloth (particularly wool) to eliminate oils, dirt, and other impurities, and to make it thicker. The practice died out with the modernisation of the industrial revolution.” ↩

- Just recently, a friend forwarded a link to a beautiful webpage describing “The Walking Purchase” of 1735 for land in Pennsylvania, a terrible example of how Europeans swindled the native people. https://express.adobe.com/page/cbFj6ku8N5IJq/. For a complete explanation of the confrontation between hunter-gatherers like the Lenape and settled, agricultural people like the Europeans, check out Jared Diamond’s book, Guns, Germs & Steel, and also The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity by David Graeber & David Wengrow. ↩

- For more on the West Jersey Society’s Great Tract, see James P. Snell, History of Hunterdon County, p.416. ↩

- Recital in West Jersey Proprietors Deed Book T p.278. ↩

- Hunterdon Co. Historical Society Archives, Ms. Deed 0018/I-103. ↩

- I do not know where that bible is kept at this time. Rockhill families do appear in a few of the bibles kept in the collection of the Genealogical Society of New Jersey, but not this family bible. ↩

- Hunterdon County Loan Office, Book A p.68. ↩

- H.C. Deed Book 4 p.107. ↩

- Vol. 1 of the Freeholders’ Minute Books, Hunterdon Co. Clerk’s Office. ↩

- Hammond Map D; NJ Archives, WJ Proprietors, Vol. N, p.429. ↩

- WJ Proprietors, Book T fol. 278. ↩

- Recital, H.C. Deed Book 9 p.78. ↩

- West Jersey Proprietors Book T p.206, NJ State Archives. ↩

- The Deats Genealogical File at the Hunterdon Co. Historical Society for the Bonnell family, states that Abraham Bonnell bought 250 acres from the West Jersey Society on the Capoolong Creek near Pittstown, in partnership with Charles Hoff, but fails to give a source for this information. I suspect Mr. Deats took it from the Hammond Map. ↩

- Recital H.C. Deed Book 18 p. 160. ↩

- NJA News Extracts, Vol. 24 pp. 67-69, the Pennsylvania Gazette No.1755. ↩

- Recital, H.C. Deed Book 18 p. 160. Benj. Coddington was almost certain related to Hoff’s wife Abigail Coddington, but I cannot say how. Abigail’s father John wrote his will in 1757 naming his 7 children, none of whom were named Benjamin. ↩

- NJA News Extracts, Vol. 24 pp. 391-92. ↩

- NJA News Extracts, Vol. 24 pp. 483-84. ↩

- NJA News Extracts, Vol. 24 p. 510; the sale was also mentioned in “Early Forges & Furnaces in NJ.” ↩

- Old Inns & Taverns of West Jersey, p.239. ↩

- From the New York Gazette or Weekly Post Boy, No.1210, as cited in NJA News Extracts, Vol. 25, p. 46. ↩

- HCHS Ms. Deeds 0018/I-044, 059; Mary C. Vail, “History of Land Titles in the Vicinity of Quakertown, New Jersey,” p.7. ↩

- Trenton Archives; microfilm available on Family Search. ↩

- See Baptistown, part two. ↩

- TLC Genealogy, 1990. This compilation of Hunterdon tax ratables for 1778-1797 lists only Charles Hoff of Hopewell, taxed in 1785, two years after the death of Charles Hoff of Kingwood. ↩

- Hunterdon Gazette, Feb. 3, 1830. ↩

- NJA News Extract, Vol. 26 (1768-1769), p. 191. ↩

- H.C. Mortgage Book 1 p.147. ↩