A continuation of the history of the Sergeantsville Inn.

Visit part one here and part two here.

Joseph Wood

As mentioned in the previous post, when Henry H. Fisher chose to take up storekeeping in Trenton in 1838, he sold the Sergeantsville store to Joseph Wood, one of the executors of the estate of Charles Sergeant, who died in 1833. Wood had married Sergeant’s daughter Permelia on March 11, 1824 when he was 23 and she was 24.1 Charles Sergeant’s will, dated February 2, 1833, made no mention of Permelia or two of her three sisters, but presumably they got a share of his estate.

When the executors of Sergeant’s estate probated Sergeant’s will, James Wolverton and James Larason swore to the will’s validity, while Joseph Wood affirmed it. This meant that Wood was probably a Quaker, although his name does not appear in the minutes of the Kingwood Friends Meeting.2 Wolverton and Larason were old Hunterdon County names. Where did Joseph Wood come from?

It seemed to me that he must be related to the Wood family of Hunterdon County. The earliest member of that family that I am aware of is Henry Wood (c.1811-c.1874, parents not known), who married Sarah Kugler about 1830. This would make him a near contemporary of Joseph Wood. But there was no Joseph Wood in the Amwell family. As it turns out, just as Henry H. Fisher was not related to the Amwell Fisher family, so Joseph Wood was not related to the Amwell/Kingwood Wood family. He was, in fact, the son of Henry Wood and Hannah Eldridge of Trenton. Henry and Hannah Wood and Joseph and Permelia Wood were all buried in the St. Michael’s Episcopal Churchyard in Trenton.3

Joseph Wood’s marriage to Permelia Sergeant suggests that he spent some time in or near Sergeantsville. Toward the end of 1824, he received an appointment from the New Jersey Legislature as a commissioner of deeds for Hunterdon County, although that could have included Trenton, which had not yet separated from today’s Hunterdon County.4 In 1825, Wood announced in the Hunterdon Gazette (Sept. 9th) that the business known as Joseph Wood & Co. was dissolving, as was the firm of H. & J. Wood (presumably Henry and Joseph Wood). But the notice did not state where this business was located. However, those owing money to the firm were to make payments to Kenneth H. Fish of Lambertville.

There is reason to think that Joseph Wood was living in Ringoes in the 1820s, because on October 13, 1825 he advertised in the Hunterdon Gazette:

“Fresh Goods–The subscriber respectfully tenders his sincere thanks for past favours to his friends and the public, and wishes to inform them he has laid in as handsome an assortment of NEW GOODS as the county of Hunterdon can boast of, and which he will sell at a very small advance – he has taken great pains in selecting his stock, and purchasing as low as the markets would admit of. As he sells only for cash and produce, he wishes to sell as low as possible, Joseph Wood, Ringoes, 12th October, 1825.5

Joseph Wood found a new business partner after 1825—one Henry K. Stout. From the following notice in the Gazette dated March 21, 1827, it appears that they had been operating a store in Prallsville.

Dissolution of Partnership. The business existing under the firm of WOOD & STOUT, was this day dissolved by mutual consent. All persons having demands against the said firm are desired to present their bills for settlement. – And those indebted are requested to make immediate payment, to Joseph Wood, who is duly authorized to settle the same. [signed] Joseph Wood, Henry K. Stout. Dated Prallsville, N. J. March 9, 1827.

I believe this was Henry Kennedy Stout (1802-1868), son of Isaiah Stout and Catherine Kennedy, and great grandson of early settlers Isaiah Quinby and Rachel Warford.6 He married Rebecca Ann Ely (1812-1838) on September 17, 1828. She may have been the daughter of Joseph Ely and Martha Williams, although I am not certain of that. By 1840, the Stouts were living in Newark.

Apparently, by 1827, Joseph Wood moved back to Hopewell (or perhaps he never left), for that year he was named postmaster of Hopewell.7 And in August, Joseph Wood of Hopewell was named a delegate to the state convention, and was a secretary of a meeting held by the Democratic Republicans on July 28th at Pennington. (This was the party of President John Quincy Adams.) Wood’s name was put on a long list of candidates for the Assembly on Sept. 5th, and he received the nomination at the county meeting held in Flemington, along with William Potts, William Stout and Samuel Cooley. But they were defeated by the candidates aligned with Andrew Jackson. Wood got most of his votes from Trenton.

On Nov. 21, 1827, the Gazette published a long notice from Joseph Wood for his store in Woodsville, offering “well-selected and cheap goods” and that he

“will allow to Farmers, in exchange for cheap goods, the following prices for produce, viz.: For new Shelbarks $ 1 per bushel. Eggs 21 cents per score [a score equaled 20; perhaps Wood threw in the extra egg to make it a penny an egg]. Roll butter 17 cents per lb . Corn 56 cents per bushel. – and in short, the highest price given for all kinds of produce.”

The earliest deed I could find for Joseph Wood was dated June 30, 1827, and involved a farm of 126 acres in Hopewell purchased from John Stillwell.8 The next year, on Feb. 1st, he was “of Hopewell” when he bought a woodlot in Hopewell from Enoch Armitage. He then sold it to Elijah Wilson on August 15th when he was “of Amwell.”9 Soon after that, the Woods moved to Trenton where Joseph Wood opened a new store. That is where he remained for most of the rest of his life, except for a brief time in Philadelphia.

This did not prevent him from continuing to dabble in Amwell real estate. In 1836, Joseph Wood bought a lot of about 39+ acres from Thomas Pratt of Philadelphia. It was located a little west of Sergeantsville, bordering Moses Larew and others.10 On February 22, 1838, Joseph Wood & wife Permelia, living in Trenton, sold that lot, now 39.44 acres, to Henry H. Fisher of Sergeantsville for $900.11 The lot bordered Green Sergeant, Cornelius Lake and Garret Wilson. Shortly afterwards, on March 2, 1838, Joseph Wood of Trenton purchased the store lot of Henry H. Fisher, Esq. of Sergeantsville for $3,000.12

By this time, Permelia Sergeant had died, either in April or May, 1839. She was 38 years old, and died only a year after moving to Trenton. She may well have died in childbirth, as she had a daughter Permelia at about that time, who probably died an infant. Permelia Sergeant Wood was buried in St. Michael’s Cemetery in Trenton.13

When he sold the Sergeantsville store, Henry H. Fisher had not yet moved to Trenton, but it seems as if he had been visiting the place in the process of setting up his new store, and probably reconnecting with Joseph Wood, whom he must have known while Wood was living in Amwell and Hopewell. Perhaps the exchange of properties was a way to help each other out.

Joseph Wood did not want to run a store in Sergeantsville. A little over a year later (on July 6, 1839), he sold it to John C. Fisher of Delaware Township for $2,001, a thousand dollars less than he had paid for it.14 The store lot was described as bordering the road from Sergeantsville to Bull’s Island and the road from Sergeantsville to Centre Bridge.

As a successful merchant and politician (by 1840 he had switched to the Democratic party), Joseph Wood did well for himself in Trenton. He served on the City Council and was twice elected its Mayor. In the 1850 census, he was identified as a “Gentleman.” He died in Trenton on May 8, 1860 at the age of 59, and was buried in St. Michael’s Cemetery next to his wife.

John C. Fisher

At first I thought the name John C. Fisher might be a misprint. Henry H. Fisher had a brother named John G. Fisher whom he persuaded to settle in Delaware Township. But that did not happen until 1853. And besides, John G. Fisher’s wife was named Elizabeth, but the John Fisher who sold the Sergeantsville store lot in 1842 had a spouse named Cornelia, and that was the name of the wife of John Chamberlain (or Chamberlin) Fisher.

John Chamberlain Fisher was born in Amwell Twp. to Jacob Fisher, Jr. (1779-1813) and Anne Chamberlin (1784-1855) on September 19, 1806. This means that John C. Fisher was a member of the Amwell Fisher family, rather than the Tewksbury family that Henry H. came from. Henry H. Fisher and John C. Fisher were completely unrelated.

John C. Fisher was only 7 years old when his father died at the age of 33, on September 24, 1813, probably from an illness. Jacob Fisher, Jr. had written his will on July 16, 1812, naming his wife Anne his executor. At the time, John C. Fisher had two older sisters (Sarah and Maria) and a younger brother (Caleb Farley Fisher); another brother died an infant in 1811. The widow Anna was certainly having a difficult time. Her father, Lewis Chamberlin died on June 30, 1813. (Her mother had died back in 1796.) Anna and her children probably went to live with her husband’s parents, but they were having a hard time too. The years of the War of 1812 seem to have been very hard on this family. Jacob Fisher, Sr. wrote his will on May 20, 1814, but managed to survive until around 1821. His will left the use of his farm to the widow of his son Jacob until her son Caleb Farley Fisher turned 21, which was in 1830, at which time John C. Fisher would be 23. What happened to Anna Chamberlin Fisher after that I cannot say. I have not found her in the census records, although she surely must be there. She was not listed in any of her children’s households in 1850, even though she did not die until 1855.

When he was 21 years old, John C. Fisher married Cornelia M. Skillman (1809–1844), daughter of Thomas J. Skillman (1781-1858) and Mary Stryker (1786–1812, another death in the war years). The marriage took place about 1827, but I have not found a record for it. Their first child, Jacob James Fisher was born in March 1828. They had five children altogether, although the youngest died an infant in 1844, along with her mother Cornelia.

John C. Fisher had inherited land from his father and grandfather, but he gradually sold off parts of it during the 1830s. On March 25, 1830, he bought a farm of 85.92 acres from Tunis T. and Rhoda Quick for $3,335.15 On May 6th he sold his rights in a farm of 149.27 acres, part of the estate of Jacob Fisher Sr., to his brother Caleb for $604.77.16 There were several other deeds on this date, all involving resolution of the Fisher estate. The farm that John C. Fisher purchased from Tunis & Rhoda Quick was sold by Fisher on April 1, 1832 for $5,050 (a nice profit) to George F. Wilson.17

John C. Fisher seems to have preferred storekeeping to farming. His store ledger books have been preserved, or at least 3 volumes of them, at the Hunterdon County Historical Society, and they begin in 1831. Fisher had gone into partnership with Hart Wilson by 1833, when they jointly bought a lot of 7.36 acres from William and Elizabeth Servis for $1660.18 The lot was located on Route 579 where it meets the Old York Road, and appears to have been the store in Ringoes. It may have been the store once run by Joseph Wood and Richard I. Lowe in the 1820s.

Fisher & Wilson were certainly ambitious. This notice appeared in the Gazette for April 17, 1833:

“What’s the Reason ? The Subscribers having suspended business for two or three weeks, in order to enlarge and repair their Store House, beg leave to say, they have again opened a New and Splendid Assortment of SPRING GOODS, Generally kept in a country store. All those who may please to favor us with their custom, may rest assured that every pains will be taken to give satisfaction with good GOODS, and steady prices. A liberal discount will be made to those who pay us cash. All kinds of PRODUCE taken in exchange for goods, at the highest market prices. [signed] Hart Wilson & John C. Fisher. Ringoes, April 9, 1833.

If there is one constant in this study of antebellum storekeepers in Hunterdon County it is that partnerships never lasted very long. The Wilson-Fisher partnership lasted all of one year. From the Gazette, Nov. 13, 1833:

Dissolution of Partnership. The partnership heretofore existing under the firm of Wilson & Fisher, is this day dissolved by mutual consent. And we beg leave to say to those who have standing accounts with us – (which has now been standing about one year.) – It is very necessary for us to solicit the payment of those accounts as soon as possible, as we are desirous of making a close of our firm business. Good merchantable Pork will be taken in payment of accounts; but no produce, except at the option of the firm. Hart Wilson & John C. Fisher.

The business will be conducted as usual at the Old Stand, by John C. Fisher. Having been to the city, and added a large supply of cheap and new GOODS to his former stock, he solicits the patronage of his friends and former customers. All kinds of produce will be taken at the highest market price. John C. Fisher. N. B. The highest market price will be given for good fat PORK. Nov. 5, 1833.

On March 1, 1834, John C. Fisher bought a lot of 31.86 acres on the Old York Road from James & Elizabeth Large, probably to have a home near his new store. On April 1, 1834, Fisher bought out Hart Wilson’s share in the 7.36 acres for $1,100.19 Then on August 13, 1834, this appeared in the Gazette:

TO OUR FRIENDS, And the Public in general. We would have you take Notice, that we have taken the STORE at RINGOES, lately occupied by Mr. R. [Richard] I. Lowe, – where we have opened a general assortment of Seasonable GOODS, and to which we would respectfully invite you to call – and see if we dont SELL CHEAP. Kirkpatrick & Fisher.

Fisher had got himself a new partner, one Alexander Kirkpatrick, son of the beloved Presbyterian pastor, Rev. Jacob Kirkpatrick of Ringoes. That partnership also lasted only one year, and was dissolved by notice given on November 5, 1834.

The store in Ringoes was continued in operation by Alexander Kirkpatrick and his brother David Bishop Kirkpatrick, presumably at the same location. But apparently this was not the same as the store lot of 7.36 acres, which remained in the possession of John C. Fisher. It was not until 1837 that Fisher decided to offer that lot for sale, as shown in a notice published in the Gazette on January 4, 1837. He described the 7.36-acre lot in Ringoes as “Bishop’s old Store Stand,” lying between the roads leading from New Brunswick to Lambertville, and from Trenton to Quakertown.” On February 25, 1837 John and Cornelia Fisher sold the lot back to William Servis for $1,775.20

I assume that after this sale, John C. Fisher continued to live on his 31.86 acres in Ringoes. However, in 1835, John C. Fisher was keeping store at Prallsville. His store ledger for that location was dated April 2, 1835 to November 10, 1835. Why he decided to quit that place I cannot say. Then his ledger continues with Sergeantsville, beginning on May 2, 1839 with his partnership with Henry Crum. On July 6, 1839, Fisher paid $2,001 for the store,21 which was described as bordering the road from Sergeantsville to Bull’s Island and the road from Sergeantsville to Centre Bridge.

After Fisher took over the Sergeantsville store, he did not publish any advertisements in the Gazette for his wares. But he did give notice on March 25, 1840 that his partnership with Henry Crum was dissolved. Henry Crum (1815-1897) was the son of Benjamin Crum and Sarah Lanning, and married Catharine Moore (1817-1891) on February 18, 1837. He was basically a farmer, not a storekeeper.

Fisher probably managed without a partner for awhile. But on June 24, 1840, he announced that he had gone into partnership with Augustus Hill “at the old store stand in Sergeantsville, under the firm of FISHER & HILL,” and

“that they are constantly receiving an excellent assortment of Dry Goods, Groceries, Hardware, Tin, Crockery, and Earthen-ware, &c., which they will dispose of as cheap as the cheapest. Thankful for past patronage, they still solicit a continuance of the same. The highest price given for all kinds of country produce in exchange for goods.”

Augustus Hill (1820-1887) was the son of Joachim G. Hill (the famous clockmaker) and Martha Barcroft. He was a single man in 1840.22 But, like all the others, this partnership soon ended. Notice was given on January 12, 1842 of its dissolution. Fisher & Hill also announced that they were “now offering the balance of our stock at reduced prices, for Cash or Produce,” suggesting that they were going out of business. On March 20, 1842, John C. Fisher and wife Cornelia Marie of Delaware Township sold the store lot of 3.26 acres to Derrick A. Sutphin for $2,500.23 I cannot say exactly what date volume three of Fisher’s ledger books ends because he arranged that volume by customer, rather than by date. But the last customer in the book made purchases on March 14, 1840. This suggests there was a volume four, and I am certain of that because some of the names in the index refer to pages greater than listed in volume three. Perhaps the most frustrating to me is that Amos Hoagland’s name was listed for what must have been volume four.

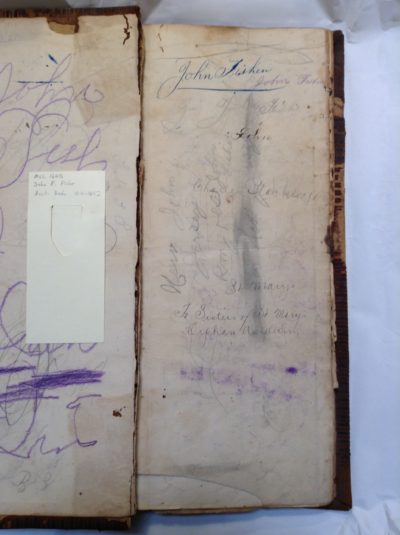

One other note on the Fisher Ledgers—after Fisher was done with them they came into the hands of one Charles Blackwell, or so it appears. His name is written underneath that of John Fisher, and below his name is written: “St. Mary’s / To Sisters of St. Mary’s Orphan Asylum.” It is clear that the sister did get these books because some of those orphans used them to practice their writing. The ledgers had become a palimpsest.

The Sergeantsville Postmaster

During the tenure of John C. Fisher, there was quite a brouhaha in Sergeantsville. When Fisher was named postmaster there on July 23, 1840, he replaced Henry H. Fisher’s old partner Amos Hogeland, who had been named postmaster on October 26, 1838.24

The reason Hogeland was replaced was that he had run afoul of Amos Kendall, the political guru who had helped build the party of Jackson and Van Buren. It was Kendall who was most responsible for the “Spoils System” as a way to build party loyalty. And since Kendall was Postmaster General under both Jackson and Van Buren, he had a perfect instrument to hand. If you were a supporter of the Whig party and happened to have gotten the job of postmaster, Kendall would soon be on your case. And so it was with Amos Hogeland.

Hogeland had apparently been a Democrat for some time, but like many others was persuaded to support William Henry Harrison, the Whig candidate for president in 1840. Hogeland attended a Harrison meeting in Delaware Township in March 1840, and agreed to be a delegate to the Young Men’s State Convention.

In June 1840 he received a letter from Amos Kendall encouraging him to promote a newspaper supporting the Democratic Party. Kendall had resigned his position as Postmaster General due to “enfeebled health,” and had taken over the newspaper “Extra Globe,” with the understanding that any profits from increased subscriptions would be his. He apparently thought his letter to all the postmasters would be a good way to increase sales. This was Hogeland’s response, which was published in the Hunterdon Gazette, August 5, 1840:

SARGEANTSVILLE, Jul 11, 1840.

My Dear Sir—I just received your polite letter, dated June 28th, 1840, accompanied with Address and Prospectus for the Extra Globe, in which you solicit my agency and influence for the purpose of procuring subscribers. My feeble efforts could avail but little in your behalf, even should I have been disposed to lend them for the object which you have specified in your communication. But I can never feel it compatible with my duty to become in any way the organ of a party, or to lend my influence solely for electioneering purposes. I hope I shall always be found on the side of Truth and Reform; and to this end, I cannot consent to circulate any views, or give currency to any measures, however distinguished may be the source of their origin, which will in anyway impair or invalidate the claims of the illustrious hero and patriot of North Bend [in Ohio, a reference to William Henry Harrison]. With due respect to yourself therefore, and a firm determination never to sacrifice principle at the shrine of party devotion, I must beg leave to decline the solicitations of your letter.

I remain, dear sir, Your friend and fellow citizen, Amos Hogeland.

The “your friend” bit imitated Kendall’s letter which was signed “Your friend, Amos Kendall.”

The Hunterdon Gazette, which was sympathetic to the Whig party under its editor John S. Brown, made much of this, with a headline that screamed “Corruption of the Administration—Mr. Van Buren’s Schemes to Get Votes.” It claimed that because Hogeland had declined to assist Mr. Kendall in selling his newspaper, he was removed, and replaced by John C. Fisher, who was in fact a Democrat, although I do not know how fervently Fisher pushed Kendall’s paper. The Hunterdon County Democrat responded on August 12th with an editorial, titled “The Postmaster at Sergeantsville.” The Democrat’s editor, G. C. Seymour, found nothing wrong in Amos Kendall’s “polite note,” and asserted that Hogeland was removed for incompetence, not for politics. In fact, some of the residents of the Sergeantsville area had gotten up a petition for Hogeland’s removal which was “signed indiscriminately by all parties, . . . and soliciting the office for the present incumbent [John C. Fisher].” The Democrat also pointed out that Kendall was not the one who removed Hogeland as postmaster, it was Kendall’s replacement, Mr. Niles, also a political operative and former newspaper owner. (If only Mr. Seymour had reproduced that petition for Hogeland’s removal. Then we would know what the claims were about his “incompetence,” and who it was who signed the petition. Perhaps it is lying somewhere in the bowels of the National Archives.) Seymour wrote:

His [Hogeland’s] attempt to get up a protest, remonstrating against his removal, was wisely abandoned, although we believe he would have been silly enough to have persisted in it, had it not been for the interference of his friends here.

Well, at least the Democrat admits that Hogeland had friends. The Gazette, meanwhile, was up in arms. Another editorial appeared in the August 19th edition titled “Corruption of the Administration.—The Postmaster at Sergeantsville.” The Gazette’s editor wrote:

Mr. Hogeland, we are informed, was for several years a merchant at Sergeantsville, and is it not strange that he is unqualified to manage a petty post office, worth perhaps not more than ten or fifteen dollars per annum? The truth is, the charge of incompetency is merely a subterfuge to shield the party.

The Democrat’s answer was published on August 26th:

In an article on the subject of the removal of Amos Hogeland from the post-office at Sergeantsville, the Hunterdon Gazette asks, “Why is it that Mr. Hogeland’s incompetency was never discovered till he abandoned the administration—till he dared to think and act for himself?”—Ask the people of the neighborhood, and they will tell you quite a different story. Hogeland’s incompetency was known sufficiently well to cause his removal. That he abandoned the administration, is not true. We understand he never belonged to it—and the only wonder is that the citizens of Sergeantsville did not sooner petition for his removal.

If you want a long history of this local scandal, check out the editorial in the Gazette of August 19, 1840, “Corruption of the Administration—The Postmaster at Sergeantsville.” I will not reproduce it here, but a year later, on July 14, 1841, the editor of the Gazette returned to the subject:

The assertion of the Hunterdon Democrat, that Amos Hogeland was last year turned out of the Post Office at Sergeantsville, on the ground of his incapacity and unfitness; and that a petition for his removal was signed by a number of citizens of his own political party, we believe to be entirely gratuitous, and untrue in point of fact. Shortly after his removal, we gave a plain statement of all the facts in relation to that act, which statement has not been disproved to this day. Mr. Hogeland is a man of respectable standing in his neighborhood, and posesses [sic] every ability requisite for discharge of the duties of his office, in which he has been reinstated by the new [Whig] Administration. He was removed, as is well known, because of his disaffection towards the Administration; and now, any attempt to injure his character, to cloak the designs of his proscribers [sic], by base insinuations, is unmanly and unjust.

Amos Hogeland got his job back as postmaster in Sergeantsville sometime before September 1, 1841.25 This was still during the tenure of John C. Fisher at the Sergeantsville store. (Fisher sold the store on March 20, 1842.) But Hogeland did not last long; he was forced out once again on December 23, 1842, when he was replaced by Samuel R. Smith.

The whole business of Hogeland’s position as postmaster had become a vehicle for a battle between the Whig-supporting Hunterdon Gazette and the Hunterdon County Democrat. In those days, newspapers were not shy about supporting one political party or another. The editor of the Gazette could not refrain from returning to the subject, in an editorial dated September 8, 1841, in which the Democrat was quoted at some length. It was noted that Hogeland had regained his job as postmaster, and quoted several comments made in the Democrat in July and September 1841, focusing on whether Hogeland was competent or not, and again dismissing the credibility of the petition to remove him. After all:

No charges against Hogeland were contained in the petition; and if any were to be made against him, why not make them publicly—why not state in the petition the grounds upon which it was got up?

What we have contended is, that Mr. Hogeland’s neighbors did not pray for his removal on the ground of his incapacity and unfitness; and this is evident from the fact that they brought no charges against him in their petition for the appointment of his successor. With their secret and unexpressed opinions or feelings we have nothing to do. Our object was to lead the public to the truth of the matter; and as the editor of the Democrat has in effect slandered the disputed ground, it is unnecessary to prolong the controversy.

How annoying that The Democrat would not publish the names of the Whigs who signed the petition. All this goes to show that keeping a country store was not always a simple business. And it was also not a very profitable one. On August 8, 1840, Amos Hogeland had sold his share in the old Thatcher property to his father, Andrew Hogeland for $1.26 That transaction had to be reconfirmed on January 30, 1843 when Hogeland was being sued for debt.27 On February 1, 1843, this appeared in the Gazette:

Bankrupt Notice, United States District Court for the District of New Jersey. In Bankruptcy. Notice to shew cause against the petition of AMOS HOGELAND, of Hunterdon county, individually and as one of the late firm of Fisher & Hogeland, to be declared a bankrupt on Tuesday the 21st day of February, inst., at 10 o’clock, A. M., at Paterson.

I have not delved into the bankruptcy proceedings, but I can say that by 1850, Amos Hoagland, age 41, was living in Trenton and working as a grocer. With him were Mary J. Hoagland age 41, and Susan, 13. Ten years later the family was living in Newark, where Amos worked as a salesman, living with wife Susan, age 52 (perhaps the name Mary in the 1850 census was an error). He died on July 8, 1876 and was buried in the Flemington Presbyterian Cemetery next to his wife who died in 1869.

Back to John C. Fisher

After selling the store in 1842, John C. Fisher may have gone back to farming or found some other employment. On February 9, 1844, Fisher’s wife Cornelia died at the age of 34 years, 11 months and 28 days. She was buried in the Larison’s Corner Cemetery and left five children, born 1828-1844, the last one dying not long after she did. Son Thomas died in 1850, age ten. The others lived well into adulthood: Jacob James Fisher (1828-1900, m. Louisa Hunt); Anna Mary Fisher (1833-1901, m. John M. Bowne), and Martha H. Fisher (1837-1906, m. John Fisher).

Not long after his wife’s death, John C. Fisher moved with his children, and probably his parents, to Newark, where he worked as a druggist. In 1847 he married his second wife Adaline in New York, and in 1850 the family was counted in the Jersey City census. They had returned to Delaware Township by 1860 for the census that year, in which Fisher was a 57-year-old farmer, with real estate worth $14,000 and personal property worth only $200. His wife Adaline was 44. Their children were Cornelia 16, Jane 11 and James 8, all born in New York. Living with them was Cornelia Skillman Fisher’s older sister Rebecca Skillman, age 56.

Sometime after this, the family moved on. They were not present in Delaware Township for the 1870 census. John C. Fisher died on March 19, 1874 in Stamford, Ontario, Canada. I do not have a death date for wife Adaline.

* * *

The next chapter introduces us to Derrick A. Sutphin, Esq., who purchased the store from John C. Fisher in 1842. It was Sutphin’s advertisement that caught the attention of Dennis Bertland and triggered this new history of the old Fisher store.

Addendum: Regrettably, as of June 2022, I still have not written that “next chapter.” It goes on my list of things to do.

Footnotes:

- I cannot say who married the couple; the marriage is not listed in Deats’ Hunterdon County Marriages, and the date was too early for an announcement in the Hunterdon Gazette. I also cannot say where this date comes from; it was in my notes from long ago, before I realized how important sources were. For more information on this family see The Sergeant Family. ↩

- The Hinshaw Quaker Encyclopedia does list a Henry Wood (Joseph’s father) and a Joseph Wood among the Philadelphia Friends, but I cannot determine if these are the same people. ↩

- Per Find-a-Grave. There is no estate recorded for this Henry Wood in the New Jersey Archives Wills Index. ↩

- Trenton Federalist, 27 Dec 1824, p. 2. ↩

- I have not been able to locate a deed for when Wood sold his store in Ringoes. Perhaps he was not the one who owned it. ↩

- For information on the Quinby family, see these Quinby articles. ↩

- Gazette, June 6, 1827. ↩

- H. C. Deed 43-037. ↩

- H. C. Deeds 44-006, 46-077. ↩

- H. C. Deed 62-272. ↩

- H. C. Deed 69-023; see also Partitions p. 295. ↩

- H. C. Deed 27-355. Deed recorded April 17th. ↩

- Mention of this daughter was found in notes pertaining to the family in the Deats Genealogical Files at the Hunterdon Co. Historical Society, but she was not buried with her mother at St. Michael’s Cemetery in Trenton. Perhaps her gravestone is missing. ↩

- H. C. Deed 72-192. ↩

- H. C. Deed 48-480. ↩

- H. C. Deed 48-412. ↩

- H. C. Deed 54-213. ↩

- H. C. Deed 57-317. ↩

- H. C. Deeds 52-300; 57-198. ↩

- H. C. Deed 69-076. ↩

- H. C. Deed 72-192. ↩

- On October 20, 1847 he married Isabella Vansyckle (1827-1908), daughter of Lewis Vansyckle and Catherine Alpaugh. ↩

- H.C. Deed 77-421. ↩

- To review Andrew Hoagland/Hogeland’s history, see Sergeantsville Inn, part two. ↩

- Oddly enough, The Postal History Book by Jim Walker states that he was not appointed until October 26, 1842. ↩

- H. C. Deed 80-425. ↩

- H. C. Deed 81-038. ↩