My previous article discussed the Bearder family and the home of Andrew Bearder, Sr. on the Locktown Flemington Road. Just east of this farm was another tract that Bearder shared with his son Jacob, but whose ownership goes back much further.

Andrew Bearder, Sr.’s homestead farm was part of Jacob Snyder’s plantation. But the farm next to it on the east was part of the 700 acres first sold by the Haddons to Daniel Robins. (For background on the Haddons, see The Haddon Tract, part one.)

Daniel Robins

I have written about Daniel Robins before,1 but just to review—on November 19, 1709, Daniel Robins, Jr. of Freehold, Monmouth County bought 700 acres of unsurveyed land in Amwell from John Haddon (by his attorney, and son-in-law, John Estaugh) for £35.2 Robins did not trouble himself to record deeds, so it is impossible to say exactly what he did with that property. He did make use of some of it for himself, but the rest was divided into smaller lots and sold, without any deeds being recorded. And Robins died in 1737 without writing a will, which also deprives us of information about his property.

What we can say for certain is that the Bearders, Andrew and Jacob, purchased the farm from William Barns/Barnes. There are two sources for this statement. First, William Barns owned the farm in 1779 when the road return for the Locktown-Flemington Road was recorded.3 Secondly, when Jacob Bearder wrote his will in 1833, he left to his three sons two farms. The first was the farm where his father lived (Block 14 lot 25). The other one (Block 14 lots 1 & 26) “adjoining it on the east side” was the one “that my father and I purchased from William Barns as by deed will appear.” Sadly, that deed from William Barns has not appeared.

William Barnes/Barns

William Barnes was born about 1720/22 to Samuel Barnes, who owned land a little north of Mount Airy on the Sandy Ridge-Mt. Airy Road. As you can see, the name was spelled in two different ways, and I tend to use whatever spelling was used in the source I rely on. You can take your pick as there was no consistency. There are very few records for William Barns, but one curious item pertains to the will of Samuel Pitcock, “plantation man” of Amwell, made on November 25, 1742. Pitcock named his two sons, John and Thomas, but did not make them his executors, suggesting that the sons were still young. He also did not name his wife, suggesting that she had died. The executors he did name were his friends Thomas Kitchen and William Barnes. The will was proved in December 1742, but an account of the estate was not given until 1761 by William Barns, with a note explaining that “Thomas Kitchin the other executor [was] rendered incapable by age.”

This is especially interesting because in 1748, William Barnes married the daughter of Thomas Kitchen. She was Hannah Kitchen, born about 1727 to Thomas Kitchen and Sarah Lambert. It is possible that the house that William and Hannah lived in is still standing, hiding underneath modern additions and alterations. Impossible to say for certain until a careful study is made of the interior, which has not been done. It is more likely that the house was built by Barns’ successor Jacob Bearder in the late 18th century.

I suspect that Thomas Kitchen gave the newly married couple a part of the land he purchased from Daniel Robins. Kitchen was certainly well-known to the Robins family. In 1737, Thomas Kitchen bordered land belonging to Daniel Robins’ son Isaac, “being part of a large tract of land formerly surveyed for said Haddon, being that plantation that Daniel Robins dec’d, father of the said Isaac Robins, formerly lived upon . . .”4

In addition to Hannah Kitchen, Thomas and Sarah Kitchen had a daughter Ann, who married Vincent Robins, a grandson of Daniel Robins. Thomas Kitchen was an Amwell freeholder in 1741, but the record of 1737 clearly shows his presence in Amwell well before that. Obviously Kitchen had acquired a large portion of the Robins 700 acres, probably before Daniel Robins died.

Other than the will of Stephen Pitcock, I have very little information on William Barns’ life. It appears that Hannah Kitchen was not his first wife. He had married Catherine “Cock” in Hunterdon County on February 11, 1742.5 Catherine might have been the daughter of Thomas Cock who died intestate in Kingwood Township in 1751. But this is shear speculation, as I have no information on Thomas Cock’s family. In any case, Catherine must have died young for Barnes to be able to marry Hannah Kitchen in 1748.

Some Background on Thomas Kitchen

Thomas Kitchen was born about 1690, the son of John Kitchen (mother not known), and brother of Henry Kitchen (c.1690-1745) and James Kitchen (1679-1761). Henry’s son Samuel was the original miller at Sand Brook. James Kitchen lived in the vicinity of Sergeantsville. Thomas Kitchen married Sarah Lambert sometime around 1725. She was the daughter of John Lambert and Rebeckah Clowes of Burlington County.

Thomas Kitchen of Amwell wrote his will on October 29, 1757, naming his wife Sarah and his three daughters. The third daughter Mercy was not married at the time, and I have found no record of her.6 The only real estate mentioned in the will was 100 acres which he left to his wife Sarah, while the daughters each got monetary bequests. Kitchen was kind enough to mention the names of his grandchildren: John, Samuel, Sarah and William Barns, and Sarah, Obadiah, John and William Robins. Witnesses to the will were Daniel Robins, George Trimmer, and Richard Rounsavell Jr. The executors were his wife and “Andrew Pierce,” a neighbor who owned land north of Kitchen’s farm.

As mentioned before, Thomas Kitchen was “rendered incapable by age” in 1761. He was probably in his 70s when he died in 1764. An inventory of his estate was taken on April 17, 1764 by Jonathan Furman, Abraham Bonnel. His will was recorded on April 18, 1764.7

In 1767, William Barns inherited 100 acres from his father Samuel near Mt. Airy, which he sold to his brother Robert in 1771. In 1780, William Barns was taxed in Amwell Township on 100 acres. There is no more record of him until December 7, 1784 when he wrote his will. He left to his wife Hannah a third of the produce of his “plantation” along with the household goods during her life. To son John he left a farm he had bought in Sussex County, and to son William Jr. he left the “plantation” where he (Wm. Sr.) lived. I find it curious that Barns consistently used the term plantation rather than farm.

Also mentioned in his will were his daughters Sarah, wife of Jacob Snyder, and Ruth, wife of Amos Robins. To each of them he left £30. He left nothing to his son Samuel, but £5 to Samuel’s sons, who were unnamed. I have no information on this Samuel; he most likely had died before 1784, especially since William Barns named his other two sons, John and William, as his executors. The will was witnessed by Andrew Bearder, Jacob Fulper, and Martin Boughner.8

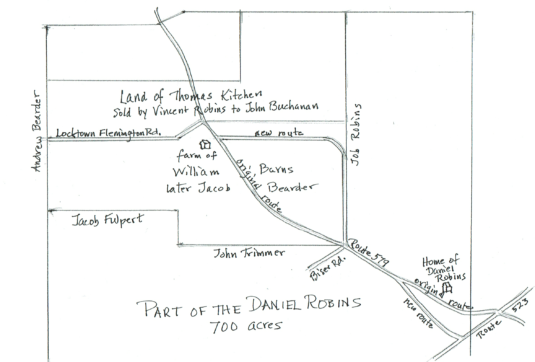

I cannot say how long the widow Hannah remained on the farm as her death has not been recorded, and the burial places for William and Hannah are not known. It was sometime between 1785 when William Barns died and 1799 when Jacob Bearder was in possession of the farm. Here is a map of the Barns plantation:

Jacob Bearder

Jacob Bearder, son of Andrew and Margaret Bearder, was born on January 6, 1768. About 20 years later he married Elizabeth Trimmer, daughter of George Trimmer and Anna Hoppock who owned land nearby. Elizabeth was born on October 6, 1769. She and Jacob had five children from 1789 to about 1810, all of whom lived to adulthood. According to Jacob’s will, he purchased the Barns farm jointly with his father. This was probably done as a consequence of Jacob Bearder’s marriage in 1789.

Jacob Bearder was a religious man and in 1790 became deacon at the Amwell Calvinist Church at Larison’s Corner in East Amwell. Perhaps it was for that reason that he was exempted from the Amwell Militia in 1792.

The Malayleck Path

Here I must make a brief detour to describe the road that ran through Jacob Bearder’s farm. We know it today as County Route 579, and in early records it is often called the road from Pittstown or Quakertown to Trenton. But the earliest records call it the Malayaleck Path, a very old Indian road that ran from Trenton all the way to Phillipsburg, across the river from Easton, Pennsylvania. About midway, the path intersected with the one that ran from Trenton to Newark, known as the Old York Road. That intersection gave rise to the village of Ringoes. The county’s earliest settlers took advantage of these well-established Indian routes to locate their own settlements.

Being an Indian path, the route to Easton took the most sensible way over a varying landscape. But this rarely conformed to the European preference for nice straight lines on their surveys. A glimpse of the maps of the early Hunterdon proprietary tracts made by D. Stanton Hammond makes that clear. Gradually over time, subdivisions of those original tracts began to conform to the location of the roads—but not always.

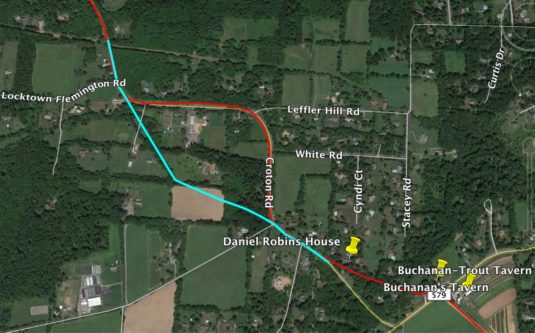

A case in point is the farm of Jacob Bearder, whose farm was bisected by the diagonal line of the Malayaleck path. Bearder did not care to have his fields divided by a road, so he went to the Court of Common Pleas in 1799 and petitioned to have the road “relayed” to run along the eastern boundary of his rectangular farm.9 And so it is that today drivers are obliged to drive that nerve-wracking curve around old Jacob’s farm.

Another change from the original route was to move the road over from its intersection with Route 523, causing drivers to struggle up the steepest part of the hill, rather taking the more sensible route, which originally ran right in front of old Daniel Robins’ house. This change was necessary, though, because the land drops down sharply from the front of the house, making it impossible to widen the road.

An Exchange of 1803

Some curious land transactions took place in 1803 involving this farm as well as the other properties owned by Andrew Bearder. On December 2, 1803, Andrew Bearder conveyed to son Jacob his 118.5-acre farm on the Locktown-Flemington Road for $2400.10 It bordered Thomas Kitchen (now Mathias Case), John Besson, Joseph, Peter and John Hoppock, other land of Andrew Bearder.

On the same day, Jacob Bearder sold his farm, or his rights in the farm on Route 579 that once belonged to William Barns to his father Andrew for the same amount of money, $2400.11 This farm was bordered by Philip Calvin, Route 579, Jacob Fulpert, and John Buchanan. The deed stated that it was “held by Jacob Bearder by right of inheritance.” This seems odd, since Jacob’s father Andrew was still very much alive.

What was going on here? I cannot imagine that Andrew Bearder, who was 62 years old by this time, would move his household into his son Jacob’s house. I can, however, imagine Jacob moving his family in with his parents to take care of them as they aged. Or perhaps this was just estate planning and no one moved at all.

Jacob Bearder’s Last Will & Testament

Some light is shed on this mystery by Jacob Bearder’s will, which he wrote on May 2, 1833 when he was 64 years old. It had been only three years since his father’s death in 1829, and one year after his wife Elizabeth died. Both Jacob and Elizabeth were buried with Jacob’s parents in the cemetery at Larison’s Corner, next to the church where Jacob was probably still a deacon.

The first provision of Jacob’s will was this (which I have paraphrased): the two farms, the one I live on at present that I got by heirship of my father Andrew Bearder the other adjoining it on the east side that my father and I purchased from William Barns as by deed will appear each farm containing 118 acres I give and bequeath to my three sons Andrew, George and Jacob Bearder, share and share alike.

Jacob Bearder died sometime before July 14, 1838, the date on which his will was recorded.12 He was 69 years old. Surprisingly there was no obituary published for Deacon Jacob Bearder in the Hunterdon Gazette.

Jacob and Elizabeth were survived by all five of their children: Margaret (1780-aft 1860), m. Josiah Rounsavel; Andrew (1794-1865), mentioned above, m. Mary Besson; Sarah (c. 1796-1855) m. Benjamin Horn, who lived on Ferry Road; George Trimmer Bearder (1803-1881) m. Mary Hann; and Jacob Bearder Jr. (c.1810-1882) m. Jane Aller.

Jacob Bearder’s will stipulated that if his sons could not agree about the metes and bounds of each share, then “the division was to be left to three men each one to choose a man and the majority of them to sett off each one’s boundary lines that to be a place of division.” As it turned out, this was not necessary. The sons worked it out for themselves, agreeing to be tenants in common, but also agreeing on who got which farm to live on.

Jacob Bearder, Jr.

The result was that Jacob Bearder, Jr. came into possession of the old Barns plantation. He was born about 1810 and married Jane Aller on October 24, 1835. She was the daughter (and one of 15 children) of Peter Aller and Amy Wolverton. Jacob and Jane Bearder had three children, Amos, born October 1840, married to Lina Dilts; Andrew, born 1844, married to Mary Catharine Bird, and a daughter Sarah, born 1851, died 1859.

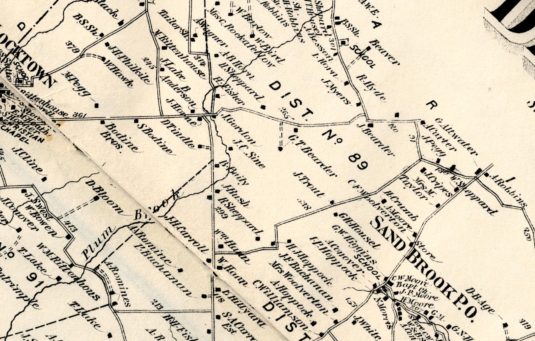

Jacob and Jane Bearder lived out their lives on the Route 579 farm. “J. Bearder” was noted in that location on the Beers Atlas of 1873.

Jacob Bearder died on October 10, 1882, age 73. Unlike his father, he merited a brief obituary in the Hunterdon Democrat, which stated that he lived near Croton. This should be taken with a grain of salt. Egbert T. Bush wrote of the family in 1929,

“Jacob Bearder owned a farm at the junction of the road with the Trenton Road. His son Amos married Lina Dilts, daughter of John Dilts, who bought the Dr. Pyatt lot after the death of John Pyatt; their son Charles Jacob is the musical professor of Sand Brook. Jacob’s other son Andrew kept the Sand Brook store for a long time and died there a few years ago. I remember that the professor’s grandfather Dilts was locally accepted as an authority on music.”13

In another article published in 1896,14 Mr. Bush wrote about Jacob’s wife Jane Aller:

“Jane Aller, born April 15, 1815, married Jacob Bearder, lived below the Harmony school house and died June 29, 1886. Her husband died Oct. 10, 1882. They had 3 children: Amos, Andrew and Sarah. Amos lives near Buchanan’s old tavern; Andrew keeps the store at Sand Brook; Sarah died when four years old.

As Bush’s statement shows, the two sons lived elsewhere, Amos near Buchanan’s Tavern and Andrew in Sand Brook. But shortly after their father’s death, they divided his estate between them.

Two deeds were filed on the same day, June 17, 1884. In one deed Jane Bearder, widow, and Andrew Bearder conveyed to Amos A. Bearder for $1025 a tract of 37.55 acres bordering the road from Trenton to Easton, Emanual Dilts, John Dilts, William Cripps, Roberson Hyde and Jesse Mires. In the other deed, Jane Bearder, widow, and Amos A. Bearder conveyed to Andrew Bearder for $2600 a farm of 114.61 acres bordering land of Amos Bearder, William Cripps, Henry Crum, Theodore M. Horn, a creek, Wm. R. Bearder, the road from Locktown to Flemington, land of Jesse Mires, the road from Easton to Trenton and ending at Roberson Hyde’s property.15

This latter property was the farm of William Barns and Jacob Bearder, Sr. Which brings me to the end of this saga.

Footnotes:

- See The Two Taverns at Robins Hill, for starters. ↩

- West Jersey Proprietors, Deed Book AAA fol. 396. For more on Haddon and his daughter Elizabeth, see Haddon Tract, part one. ↩

- H. C. Road Records, Book 1 p. 101. ↩

- NJ State Archives, Hunterdon Co. Loan Office, March 25, 1737, p. 20. ↩

- William Nelson, ed., New Jersey Marriage Records, 1665-1800. ↩

- There is a clue to Mercy Kitchen’s identity in Thomas’ will. The account of his estate, which was rendered on April 27, 1770, includes a legacy paid to a Mary Lewis She was probably related to Dr. John Lewis, who witnessed the wills of James & Henry Kitchen in 1745. John Lewis of Sergeantsville is one of my favorite odd characters of 18th century –. Problem is, Dr. Lewis’ wife Mary seems to have died in 1764, so the legacy could not have been paid to her. And she did not have a daughter named Mary. So much for that theory. ↩

- On April 27, 1770, an account of the estate was submitted by Andrew Peairs, surviving executor. The list of bequests is an interesting one; the names are Sarah Barnes, William Barnes, John Peters (a legatee), Sarah Robins, (nephew) Samuel Kitchen, Mary Lewis (probably related to Dr. John Lewis, who witnessed the wills of James & Henry Kitchen in 1745), Samuel Barnes (a legacy), Andrew Pierce (legacy), William Barns (legacy), Ann Robins (legacy). ↩

- Two inventories were made of the estate. The first, on June 7, 1785, was made by Peter ‘Bellies’ (Bellis) and John Teeple. The second, on September 19, 1785 was made by Peter Bellis and Andrew Bearder. It will take a trip to the State Archives to get a look at these inventories. ↩

- Hunterdon County Court of Common Pleas, Minutes, Book 15 p. 868. ↩

- H. C. Deed Book 9 p. 38. ↩

- H. C. Deed Book 9 p. 34. ↩

- His grave is included on Find-a-Grave, along with his wife’s, but no dates are given. ↩

- See “Boarshead Tavern.” ↩

- “Croton and Vicinity,” Hunterdon Republican, July 22, 1896. ↩

- H. C. Deeds Book 206, pp. 14, 17. ↩

Marshall Lake

December 10, 2017 @ 12:25 am

Marfy,

I think Vincent ROBINS was a son of Isaac ROBINS (1700-1741) rather than Daniel ROBINS.

Marfy Goodspeed

December 10, 2017 @ 7:55 am

You are right, Marshall. My mistake.

Marshall Lake

December 10, 2017 @ 2:19 pm

Marfy,

In the photo above (compiled by Marilyn Cummings) the house of Daniel ROBINS appears “pinned”. Is that an indication that the original house of Daniel ROBINS still exists? If so, have you ever done a house history?

Marshall

Marfy Goodspeed

December 10, 2017 @ 3:55 pm

Marshall, you can find some history for the Daniel Robins house in this article: https://goodspeedhistories.com/the-two-taverns-at-robins-hill/

Barb Oleson

January 31, 2019 @ 4:06 am

Just read about the Bearders, in my dad’s mom’s side i believe there is a Lizzie Bearder,can’t remember who she was married to,it might be my dad’s grandma,maybe born after 1870? His mom is a Sheaf,but her mom may have been a Bearder. The other possibility is Lizzie married into the Parent family, his name was Nathaniel Parent who is my dad’s grandfather,please let me know if you have any info,also a William Johnson connected with the Sharp family,could be a relative,my mom’s grandmother was Emma Johnson,and I think her brother was William Johnson,the dates were about right.thx

Marfy Goodspeed

January 31, 2019 @ 8:09 am

Barb, I do have an Elizabeth ‘Lizzie’ Bearder, born 1869, in my database, who married Burroughs Parent in 1886. Trouble is, I haven’t connected her up with the rest of my Bearders. Until now. Thanks to your query, I studied the Bearder families I’ve got and found that I neglected to list Lizzie as a daughter of Cyrenus Bearder and Emily Bosenbury. She shows up in their family in the census records of 1870 and 1880. I’ll have to fix the family tree. What is especially neat about that is that Cyrenus will be appearing in my next blog post on Sandy Ridge. Thanks for calling my attention to this omission.

Lisa Barnes

June 19, 2019 @ 12:36 am

Hi Marfy, I am a descendant of William Barnes. I just stumbled upon this site and I’m thrilled to see you have located Williams father. I was out at Flemington a few years ago to search the historical society collection but never found Williams father.

FYI several Barnes family members are buried in Ramseyburg cemetery.

The Barnes family left hunterdon and lived in Warren and Sussex counties. My branch of the family left Sussex county in 1940 and moved to Northern California.

Can you tell me any documentation you have on Samuel?

Richard Williamson

June 22, 2019 @ 10:44 am

You have helped soooo many people, Marfy. Thank you very much.