Last Sunday, I gave a talk to the Lambertville Historical Society about how to research one’s property in Hunterdon County, with a special focus on Lambertville. It was a great group of people, and I got a chance to appreciate how awesome old photos look when projected on an enormous screen. It was also nice to show many more pictures than I can reasonably do on this blog.

Researching a property in a town like Lambertville can be quite different from researching one out in the hinterland (like most of Hunterdon was in the 19th century). There are challenges, but there are also advantages. Despite the differences, there are certain things that apply to all properties and all house histories.

I have written about doing House Histories before, as you can see on the home-page where my two articles are featured. I will be repeating some of the advice in those articles, but this time with Lambertville in mind.

Architecture

Since so many Lambertville houses were built after the Civil War, I thought it made sense to consider using a house of that vintage as a model for researching a house’s history. Andy and Caroline Armstrong very generously agreed to have their house used as my model.

As you can see, it is a very attractive house, probably built in the later years of late 19th century. One of the things I stress for people wanting to learn how to research their houses is to acquaint themselves with the architecture of their house. That’s not hard to do in Lambertville, when so many houses are of the same vintage.

As you can see, it is a very attractive house, probably built in the later years of late 19th century. One of the things I stress for people wanting to learn how to research their houses is to acquaint themselves with the architecture of their house. That’s not hard to do in Lambertville, when so many houses are of the same vintage.

Architecture is an important clue to the date of a house. After all, you can’t pin down who built the house unless you have a general idea of when the house was built, and that answer comes from its architectural style.

If you’re not familiar with architectural styles, it helps to consult the Historic Sites Survey conducted by the Cultural & Heritage Commission in the 1970s. Although the surveyors missed quite a few houses, the book is still very thick and definitely worth checking to see if your house is included.

Unfortunately, if you live on the west side of Main Street in Lambertville, you are out of luck. The C&H Commission left the job of surveying those houses to the D&R Canal Commission. The Commission did do the survey, but the documents are at the moment hiding in a DEP warehouse.

However, you can contact the executive director of the Canal Commission, John Hutcheson, if you want to see if there is a survey of your property. Give him the address, and he will look it up, scan the page and email it to you. I think that is pretty nice of him. His phone number is easy to remember: 609-397-2000.

And the good news is that John is hoping to have the property assessments scanned and available on the Commission’s website sometime later this year.

Maps

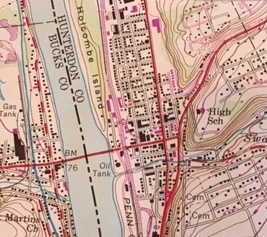

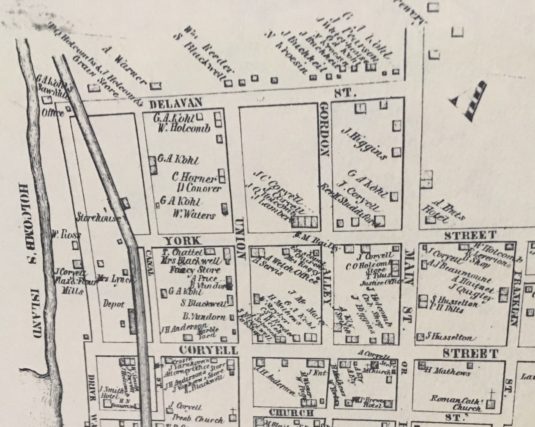

I always stress at the beginning of a project like this the importance of the wonderful old maps available for Hunterdon County. You’d be amazed at what they can tell you. Aerial photos are great for locations in the countryside because the hedgerows are usually clues to early lot lines.1 For residents of small cities like Lambertville, aerial photos don’t help all that much. Topographical maps, however, especially early ones, are more helpful. Here is one of Lambertville in the 1950s.

I always stress at the beginning of a project like this the importance of the wonderful old maps available for Hunterdon County. You’d be amazed at what they can tell you. Aerial photos are great for locations in the countryside because the hedgerows are usually clues to early lot lines.1 For residents of small cities like Lambertville, aerial photos don’t help all that much. Topographical maps, however, especially early ones, are more helpful. Here is one of Lambertville in the 1950s.

Of course it’s not the topography so much as the location of buildings that interests us. These maps are produced by the USGS. You can view them online and order a map. Obviously more recent maps will show many more buildings than older ones like mine.

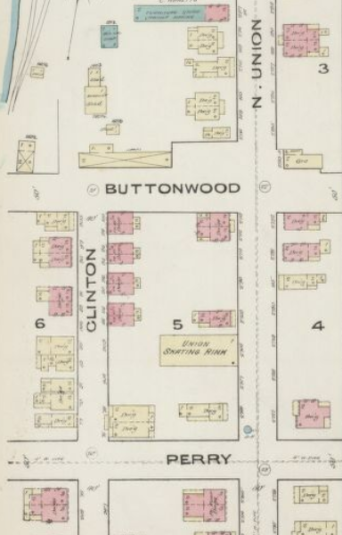

The first map that actually pinpoints the location of the Armstrong house is the Sanborn Fire Insurance Map.

These Maps were published over a period of several years from 1885 to 1923. If you live in Flemington, Clinton, Lambertville, or any of the larger towns in Hunterdon, these insurance maps can give you an exact picture of the layout of the house and its location.

These Maps were published over a period of several years from 1885 to 1923. If you live in Flemington, Clinton, Lambertville, or any of the larger towns in Hunterdon, these insurance maps can give you an exact picture of the layout of the house and its location.

You can see the 1895 version on microfilm at the Lambertville Historical Society, and the County Historical Society also has copies. But I like the Library of Congress website because it’s easy to copy the images. There are several other places to find copies of the maps, including www.historymapping.org.

The Armstrong house is on North Union St., between Perry and Buttonwood, on what is designated as Block 5, as you can see in this detail from the 1885 map. The Armstrong house is in about the middle of the block, just above the “Union Skating Rink.” (Color code: Pink means a brick building, yellow means a wood frame building.) By 1890, the skating rink was gone, replaced by another house.

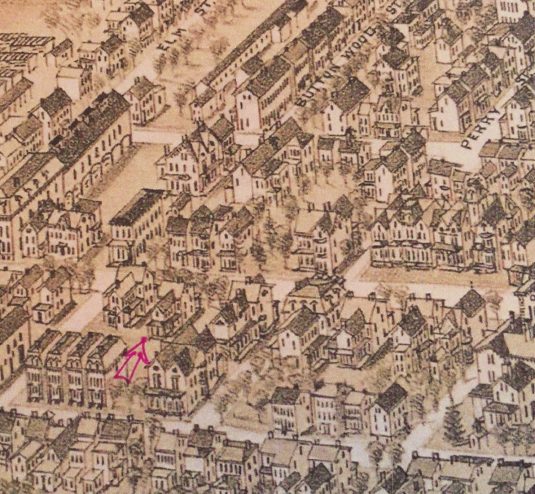

Perhaps the loveliest map of all is the Bailey Map published in 1883. I’d love to show the whole thing, but I must confine myself to a detail focused on the Armstrongs block. The house is indicated by a red arrow. For some properties I’m sure this map a godsend. But the Armstrong house is on the wrong side of the street, so you can only get a partial view of the back of the house. This leads me to the maps that provide the most information—the historical atlas maps. These are 19th century maps that locate houses and include the names of the owners. This is why you should visit the historical societies or the County Library to check on these maps before going to the Search Room to look up your deeds. I discussed these maps in my first article, “Secrets to a Great House History,” but I want to review them in light of the Armstrongs house.

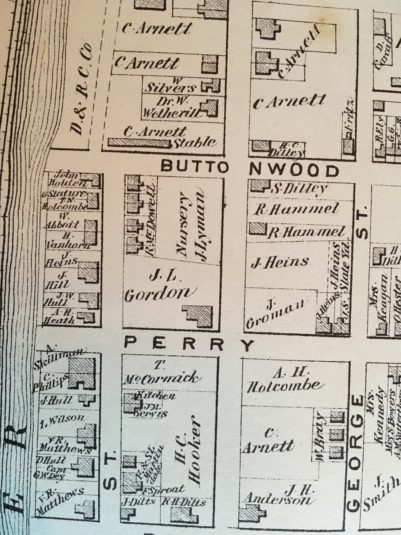

This leads me to the maps that provide the most information—the historical atlas maps. These are 19th century maps that locate houses and include the names of the owners. This is why you should visit the historical societies or the County Library to check on these maps before going to the Search Room to look up your deeds. I discussed these maps in my first article, “Secrets to a Great House History,” but I want to review them in light of the Armstrongs house.

There are three key maps: The Beer’s Atlas of 1873, The Map of Philadelphia & Environs of 1860, and Cornell’s Map of Hunterdon County, published in 1851.

The Beers Atlas of Hunterdon County is a treasure. And in the book version, Lambertville gets a four-page spread! If your house does not appear on this map, then you know it must have been built after 1873.

Check out the block between Perry and Buttonwood. There’s only one house on that stretch of North Union, on a lot owned by J. L. Gordon. The rest of the street is a nursery. Now we know that the Armstrong house was probably built before 1890 and definitely after 1873.

Check out the block between Perry and Buttonwood. There’s only one house on that stretch of North Union, on a lot owned by J. L. Gordon. The rest of the street is a nursery. Now we know that the Armstrong house was probably built before 1890 and definitely after 1873.

Even though the Armstrong house was built after 1873, it’s worthwhile looking at the earlier maps of Lambertville. The next map is the Philadelphia Map of 1860. I was not able to get a good photo of Lambertville from that map so I will skip over it, because the one before that, the Cornell Map of 1851 is very similar. And also very important.

This is a detail from the Cornell Map. Notice that there are no streets north of Delevan Street. In 1851 that’s as far north as Lambertville went.

The Cornell Map has special importance for Lambertville’s history. The very year that it was published was the year that the Bel-Del railroad came through—1851. As you can imagine, the railroad attracted a lot of industry. Industries need workers, and workers need a place to live.

There’s an interesting item in James Snell’s History of Hunterdon County, published in 1881. In the section on Lambertville he wrote: “All the houses and places of business which we now see above Delevan Street have been built since the autumn of 1857.” Well, we can see that is not exactly true, since there were buildings on the north side of Delevan in 1851, but clearly there was very little development at the time. 2

The Deeds

In previous articles I have discussed the work of researching a property’s deeds and creating a Chain of Title. As those articles emphasize, the Recital in a deed leads you to the previous deed, so it can be very frustrating when there is no Recital. Fortunately for me and the Armstrongs, every deed in their chain contained a Recital leading not only to the previous owner, but also to the previous deed (by date, book and page) in the chain.

Probably the best way to keep tract of the information you collect in your searches is in a timeline in which all your documents are listed chronologically with a summary of what they contain. Start with the deeds you’ve found and add in information you collect as you widen your search from land records to personal and genealogical records.

When listing deeds, it is important to include bordering owners and a summary of the recital if there is one. Add in names from historical maps, and any relevant information you pick up about the owners.

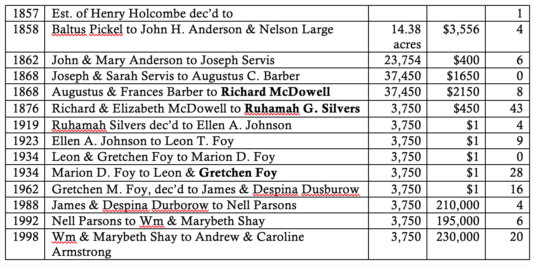

Once you have found all your deeds and gotten a nice Timeline for your property, you are ready to think about which of those owners built your house. One of the best ways to do this is to make a chain of title.

Here is a basic chain of title for the Armstrong property. This is different from the Timeline because it gives the bare essentials in table form, which makes it possible to see what’s happening over the years.

Take a look at how the lot size changes as well as changes in the value of the property. It may be that the price jumps significantly between two deeds—that is a hint that a house was built then. See if the timeframe fits with the architecture.

Take a look at how the lot size changes as well as changes in the value of the property. It may be that the price jumps significantly between two deeds—that is a hint that a house was built then. See if the timeframe fits with the architecture.

Another tip is if the lot gets divided. Since we suspect that the Armstrong house was built sometime after 1873, notice who bought the property in 1868—Richard McDowell. He bought a large lot for $2150 that year. But in 1876 he sold a much smaller lot for $450. (Can you imagine spending $450 for a lot in Lambertville?) It appears that McDowell subdivided his lot, built a house on it, and sold the house and lot in 1876.

Note that the first owner after McDowell is Ruhamah Silvers, who remained in the house for 43 years. That also suggests to me that McDowell was the builder.

And finally, scroll back to the detail from the Beers Atlas, which shows that just around the corner on Clinton Street, there are four houses owned by “R. McDowell.” That tract, with the four houses and the nursery lot must be the lot that McDowell bought from Augustus & Frances Barber in 1868. So he was busy building houses on the Armstrong block as early as 1873.

This leads us to the next question: Did he build the Armstrong house for himself or did he build it to be sold? To answer that, you need to check out all his deeds.

McDowell’s name appears frequently in the Grantee Index, meaning he bought a lot of property in the 1870s and 80s. He also sold a lot of property, as a search of the Grantor Index will show. It seems that Mr. McDowell was a developer.

When dealing with a developer or land investor, a good recital pointing to when he (usually a ‘he’) purchased the property you’re investigating is essential. Otherwise, you have to plow through all his purchases looking for the lot that matches yours. Luckily, the recital for the McDowell deed is perfectly clear.

Just to be thorough, I checked to see whether McDowell purchased a lot from either J. L. Gordon or J. Lyman. I did find deeds recorded for John L. Gordon, but none of them were to McDowell. As for J. Lyman, there were no deeds recorded at all for him, so he was most likely a tenant on property owned by McDowell.

Can we now figure out exactly when McDowell built the Armstrong house ? To be absolutely certain would take extra research. An exact date may never be found. It hardly ever is. Usually an approximate date is the best one can get. For the Armstrongs, the approximation is very good—between 1873 and 1876.

Who Were These People?

Now that we’ve got the chain of title, it’s time to find out more about who the owners were.

Just a reminder– The earliest owner of your property is usually not the person who built your house. And deeds will not tell you if or when a house was built. To figure that out you must build up a circumstantial case, but one that rests on established facts. Let’s see what we can learn about

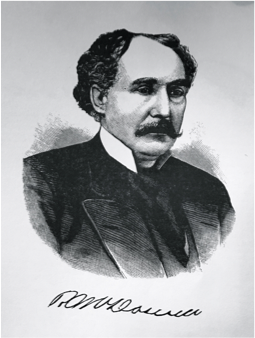

Richard McDowell

I always start by searching for census records. Richard McDowell and family appear in the 1850 Census living in Luzerne County, Pennsylvania. Richard was age 25, born in Ireland, working as a machinist. He is married to Elizabeth, age 23, born in Wales, and they have two children.

Ten years later, in 1860, the family is living in Lambertville, and that’s where McDowell spends the rest of his life. By 1870 he has become a master machinist. In 1880 he is located on Lincoln Avenue, which is on the south side of Lambertville, not at all close to the Armstrong house. He is then a master mechanic. In 1900 he has retired.

The census of 1900 includes the year that a person immigrated to America. For McDowell it was 1831, when he was only 7 years old. His wife Elizabeth immigrated in 1832. Since they immigrated as children, immigration records might help identify their parents.

Next step is to check Find-a-Grave, which has become a very helpful website since it first started up. The page for Richard McDowell gives his death date as 1903, age 79, and his burial place the Mt. Hope Cemetery. His wife Elizabeth died in 1905 and was buried next to him.

If you’re lucky, as in the case of McDowell, you will find the obituary included, saving you a lot of trouble looking for one in the old newspapers.

Obituaries are wonderful things. McDowell’s tells us that he was “one of Lambertville’s most prominent citizens,” and “was chosen the first mayor of Lambertville upon the adoption of the city charter in 1872.” Well—that gives the Armstrongs some bragging rights!

Let’s check out Snell’s History of Hunterdon County. McDowell shows up on several pages. There we learn that he was developing tracts of land in Lambertville as early as 1871 when he built some houses on the east side of Mount Hope Cemetery. We’ve already learned from the 1900 census record that he was living over there, on Lincoln Avenue. Snell also tells us that he served on the board of directors for the Lambertville Gas Co. and the Lambertville Water Co. Best of all, the book has a portrait of Richard McDowell.

Whenever you can get a portrait of one of your owners, it’s a real bonus.

Whenever you can get a portrait of one of your owners, it’s a real bonus.

McDowell probably got his portrait into Snell’s history because he was an “Important Man.” And also, probably, because he made a contribution to support the production of the book.

Of course, I’m never satisfied. I wish they had included a portrait of Elizabeth McDowell, but that sort of thing was not done in the 1880s when Snell was published.

There is a very nice book called Lambertville’s Legacy—The Coryells, Ashbel Welsh and Fred Lewis by Edward Cohen. You will find Richard McDowell in that book. The caption to his portrait reads: “Richard McDowell, a colorful Bel-Del family gentleman, who was highly competitive, goal-oriented, and certainly eccentric.”

McDowell was hired as the master mechanic for the Belvidere-Delaware Railroad. Apparently he was very strict about the working conditions in the Bel-Del shops that he supervised. He would show up wearing white gloves so he could be sure everything was spotless.

The book also mentions that the railroad wanted to build their station where McDowell’s home was located. The railroad bought him out and compensated him with the stone and timbers needed to build a new home, which he constructed on Lincoln Avenue. If only there was a picture of that earlier house before it was torn down to build the railroad station.

To summarize what we know about McDowell so far, he was an Irish immigrant who arrived in Pennsylvania in 1831. He was born near Dublin on January 8, 1824. Elizabeth Hosley, born in Wales on July 15, 1826, immigrated to Pennsylvania in 1832. The couple married about 1845, and were living in Hazle, Luzerne County, Pennsylvania in 1850 with a son John age 4 and daughter Mary Selena age 1. Richard was employed as a machinist. By 1860, the family had moved to Lambertville, having added another daughter, Anna. By 1870, they had a third daughter and two sons. By that time, McDowell had added the role of developer to his occupation of machinist.

Purchase of the Lot

Let’s take a look at McDowell’s purchase of the lot on North Union Street. The deed was dated October 13, 1868 (Book 141 p. 330), in which Augustus C. Barber & wife Frances A. Barber of the Town of Lambertville conveyed to Richard McDowell of same, for $2150, a lot of 37,450 square feet, which the Barbers had purchased from Joseph Servis the same year.

An examination of the deed index shows that this was one of McDowell’s earliest land purchases in Lambertville. Many more followed. I added up the number of deeds recorded for him as a grantor; the total came to 161. His biggest year was 1883 when he sold 23 houses. McDowell died in 1903, but there were twelve sales after that date, the last one being recorded in 1938. And that brings up an important thing to remember: the deed index lists deeds by the date of recording, not the date of the deed. So, that deed of 1938, could very well have an actual date of 1904, since it was sold by the estate of Richard McDowell.3

Between the time McDowell bought the Barber lot and the time he sold a house to Ruhamah Silvers, he embarked on a project on the other side of town. As Snell wrote:

“In 1871, Mr. Richard McDowell purchased the tract east of Mount Hope Cemetery, opened several streets and divided the tract into building-lots. This has grown to be a very pleasant part of the town, known as Cottage Hill, from every part of which a fine view can be had of the surrounding country.”4

It would be interesting to see if his house is still standing. According to the 1900 census, it was located at 221 Lincoln Ave., but street numbers may have changed since then.

Even though McDowell was busy managing a minor real estate empire, he worked as a machinist all his life, until his retirement in 1900. He was always employed by the Belvidere-Delaware (later Pennsylvania) Railroad.

Richard McDowell died on April 27, 1903 age 79, and his wife Elizabeth died on Nov. 9, 1905 also age 79. The couple is buried in the Mount Hope Cemetery along with many other McDowells.

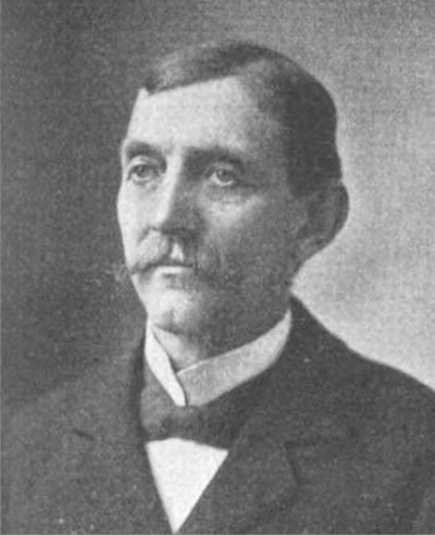

Ruhamah Silvers

On June 24, 1876, Richard McDowell and Elizabeth B. McDowell, his wife, of the City of Lambertville conveyed to Ruhamah C. Silvers, wife of Edward Silvers of same place, for $450, a certain lot of land & premises in the City of Lambertville of 3,750 square feet, beginning at the northeast corner of a lot belonging to the estate of John L. Gordon deceased . . . being part of a lot conveyed to said McDowell by Augustus C. Barber and wife.5

The deed stated that “Union Street is fifty feet wide and to be kept open that width for public use and public travel.” It was of course a dirt road, as all streets were in the 1870s.

I had originally written that “In contrast to Richard McDowell, about whom there was a great deal written, Ruhamah Silvers is a mystery.” Perhaps to me, but as you can see in the comments below, not to Ian Schoenherr, who managed to identify her family and her husband Edward Silvers. So I have rewritten this section to accommodate the new information.

Ruhamah was born Ruhamah G. Allen on July 10, 1848. She was the third child of Daniel and Ann Allen of Quakertown, Franklin Township, Hunterdon County. In 1860, when she was 12, Ruhamah went to live with the family of Amos and Amelia Shepherd in Raritan Township. On December 17, 1867, Ruhamah Allen of Somerset County was married to Edward Silvers of Lambertville. One wonders how they met.

In the 1870 census, Edward Silvers 23, carpenter is living with his parents, John and Rebecca Silvers. His wife Ruhama was also in the household, age 22, and listed as a boarder, which seems odd. Their first child Frank was probably born not too long after this census was taken.

When Ruhamah Silvers bought the Armstrong house, her deed made note of the fact that she was a married woman. Ian Schoenherr managed to dig up from Google Books an item that explains why the property was in her name.

It was found in Pennsylvania Railroad System Information for Employees and the Public, 1915, vol. 3-4, p. 6, and described the service of Edward Silvers as a railroad employee. He had been employed by the railroad for 50 years and 7 months. His father, John Silvers worked as “Master Car Builder” for the Belvidere-Delaware Railroad until his death in 1871.

Edward Silvers began work at the railroad in 1864 when he was only 15 years old, working as an apprentice carpenter. He graduated to “Carpenter in the Car Shops” in Lambertville until 1871 when he was sent to Jersey City to “assist in erecting bridges and trestles leading from Jersey City to Harsimus Cove.” It is not clear how long Silvers remained in Jersey City, but I suspect he left his wife and children behind in Lambertville.6

In other words, when Ruhamah Silvers bought the house from Richard McDowell in 1876, she was probably on her own. This may have been a considerate gesture on the part of McDowell, who no doubt was well acquainted with Edward and his father John Silvers. And the timing may have been connected to the fact that the Silvers’ second child Olivia was born the year the house was bought, 1876.

I searched the deed index to see if the Silvers bought any other properties, and only found a land purchase recorded in 1889 from Ralph Sutphen dec’d.7 But no sale of this property was recorded. Ruhamah’s purchase from McDowell was the only one in her name.

Once the bridge & trestle work was completed, Edward Silvers returned to Lambertville, but in 1907 he was sent to work in Trenton, where he remained until being placed on “the Roll of Honor” in 1915. Presumably he returned again to Lambertville, where he died in 1919. But in the meantime, Ruhamah had died on December 7, 1913. She and her husband were buried in the Mount Hope Cemetery.

On September 15, 1919, following the death of Edward Silvers, the heirs of Ruhamah Silvers, Frank and Olivia (who were also the executors) sold the house and lot to Ellen A. Johnson, wife of Fisher C. Johnson, of the City of Lambertville for $1.8 By the 20th century, people preferred to keep the amount they paid for properties private, as long as there was some “consideration,” hence the common use of the amount of $1.00.

Like the purchase by Ruhamah Silvers, this was a case of the wife purchasing the property in her own name, even though her husband seemed to be competent to do so. This was the first typewritten deed in the Armstrong chain of title. All previous clerk’s copies were handwritten. Unlike Ruhamah Silvers, Ellen Johnson only kept the house for four years before selling it again.

As you can see from this partial house history, there are all sorts of unanswered questions, many possible lines of inquiry to pursue. That’s part of the joy of researching old properties—the hunt. It’s not unlike a good detective story. Probably the first step I would take at this point is to visit the Surrogate’s Court and look up the estate records for Richard McDowell and Ruhamah Silvers. I’m sure a lot can be learned there.

Another place to look is the newspapers. The Beacon would be the most informative, but the Hunterdon Republican did include notices that McDowell was reelected Mayor of Lambertville in 1885 and 1886. One other item from 1879 is of especial interest:

News from Lambertville. Cornelius Smith, the popular Constable, has just finished building several nice residences for Richard McDowell and is now erecting two brick dwellings for Miss Ann Horton. His facilities for building are excellent and he does his work in good style.9

Footnotes:

- An excellent resource is the website: www.historymapping.org. It has a vast amount of information about Hunterdon history overlaid on Google Earth views. The site was created by Marilyn Cummings, and you really should check it out. ↩

- The statement by Snell raises the question, what happened in 1857? I don’t know the answer to that, not having done the research. ↩

- I ran out of time before publishing this article, and was unable to get to the Hall of Records in Flemington to look up this deed to get its actual date. It is recorded in Book 414 p. 82. ↩

- Snell p.283. ↩

- H. C. Deed Book 168 p. 184. Although the deed stated that Ruhamah’s middle initial was a C., census records wrote it as G. Since they are so similar, I’m not sure which one was right. ↩

- I should note, however, that Silvers was present in Lambertville for each of the census years, except perhaps for 1900, when the Silvers house was missed. ↩

- H.C. Deed Book 223-339. ↩

- H. C. Deed Book 331 p. 187. ↩

- Hunterdon Republican, Nov. 6, 1879. ↩

Ian Schoenherr

February 9, 2019 @ 8:52 am

Maybe you have this info, but just in case:

Ruhamah G. Allen was born 21 July 1848 in Franklin Township – daughter of Daniel and Ann Allen.

1860 Census: Ruhamah was living with farmer Amos Shepherd and wife Amelia in Raritan Township.

Ruhamah G. Allen (of Somerville) and Edward Silvers (of Lambertville) married 17 December 1867 at M.E. Church of Somerville.

Marfy Goodspeed

February 9, 2019 @ 9:20 am

Thank you, Ian! I figured the Silvers must have been out of county to be so elusive. Nice work.

Kyle Keiderling

February 9, 2019 @ 3:00 pm

Nicely done. Enjoyed reading it.

Ian Schoenherr

February 9, 2019 @ 9:00 am

…and on the 1850 Census: Ruhamah father’s Daniel Allen (did I put David in my last comment?) was a constable, aged 29, living in Franklin Township, Hunterdon County – with wife Ann, 28, and Mary E., 4; Patience A., 2; Ruhama [sic], 1; and Azuba McCann, 67.

Linda Lyons

February 9, 2019 @ 9:48 am

When I was looking for my great-great grandfather’s house on Delavan St. in Lambertville, I was initially confused by the house numbers. According to 1880 Census, he lived at 16. Looking at 16 Delavan today, one sees a side yard that is clearly part of the original house to its right. What became clear eventually with the help of someone from the historical society was that the houses were renumbered in the 1890s. My ancestors lived at what is now 14 Delavan. This renumbering will effect other’s research too.

Scott

February 11, 2019 @ 3:54 pm

Very interesting! Having researched the first baseball team in Lambertville, I can add that A.C. Barber was one of the club directors during the second year of the Lambertville Logan Base Ball Club in 1866. He later served as President of the Lambertville National Bank by 1896.

Goodspeed Histories: February News

February 26, 2019 @ 11:16 am

[…] February 9, 2019: Researching an old house in Lambertville can be a lot of fun. […]

Linda S

July 22, 2019 @ 8:04 pm

So informative! Thanks so much! BTW, there is a copy of the D&R Commission Historic Structures Survey book in the reference room of the Lambertville City Library.