When writing about Pine Hill Cemetery recently, the name of John Lewis came up. This reminded me of a wonderful article written by Jonathan M. Hoppock back in 1905 about a mysterious character named Ticnor Lewis who lived not far from Pine Hill. It is one of Mr. Hoppock’s most colorful yarns, and one of his many stories of the early settlers in Amwell Township. This one is based entirely on folklore or family tradition. A bowl-full of salt is highly recommended.

The Old Oak–A Scrap

of Local History

by Jonathan M. Hoppock

published in the Democrat-Advertiser, August 3, 1905

Standing on the handsome homestead of Mr. Kensyl Reading, near his dwelling, a short distance north of the village of Sergeantsville, is this noble old oak. Under its spreading branches is a spring of the purest water, from which issues a rivulet clear as crystal, forming—with the waters of other springs a short distance away—a stream of sufficient volume that in times past, set in motion the wheels of three different mills used for grinding and sawing purposes. From its source to where it mingles its waters with the romantic and rapidly flowing Wickecheoche [sic], its length is less than one mile.

This small creek is known as Cold Brook or Cold Run. It runs parallel with Reading Road in Delaware Township and meets the Wickecheoke just above the Covered Bridge. In the 19th century it powered the mills belonging to Charles Sergeant and his son Green Sergeant. Kensyl Reading’s home was on Reading Road. On the tax map it would be Block 22, lot 1.

In old colonial times, before the keen axe of the settler laid low the primeval forests, it was said that no part of Hunterdon was covered with a thicker growth of gigantic oak, hickory and other hardy forest trees than were found standing along the banks of this beautiful little stream. These dense forests afforded a place of hiding for the panther and other wild animals, natives of this region long after the first settlements were made.

From a few extant deeds and unwritten facts, kept alive by memory connected with the early settlement of this part of the State, it is evident that the first settlements were commenced nearly two hundred years ago. Among the early settlers, consisting of the Gordons, Williamsons, Wolvertons, Sergeants and others, who cleared the land and made this region their permanent home, was a man named Ticnor Lewis, who, for a time, by purchase or otherwise, held possession of the premises now owned by Mr. Reading, and erected his log cabin near the spot where the old oak now stands. 1

Editorial: The term “unwritten facts” brings a smile to my face. Mr. Hoppock was known to be somewhat credulous. He was happy to believe that a story told to him was a fact, as long as it was a good story. He was (and is) not alone. Since I have many comments to make on this article, I will let Mr. Hoppock have his say first.

The writer, in his youth, on many a winter evening, was an eager listener to the tales told by then aged citizens, while seated in front of a glowing fire on the kitchen hearth, about this old settler (Lewis), they in their youth having heard them repeated by their grand sires, who were among the early pioneers of this part of the country.

Notably among the number of the generation gone hence who loved to talk of facts relating to local history, was an aged maiden lady named Charlotte Gordon, daughter of Othniel Gordon, who owned the farm (a part of the original purchase made by his father) adjoining that now owned by Mr. Reading.

Her description of the old settler, as well as that of others of her generation, was far from flattering. He was spoken of by them as a blood-thirsty looking fellow, of a vicious and morose disposition, grotesquely dressed,2 and holding but little intercourse with his neighbors. No one was allowed to enter his cabin. His career previous to settling here was a mere matter of conjecture, and his eccentric habits excited the curiosity of the settlement. Mysteriously disappearing for days at a time, his return would be made in the same manner in which he took his departure, from a place no one knew whither or whence. It was stated that these weird journeys to and from parts unknown were always made in the night time. Finally, the old settler disappeared for good, and his last departure was as much of an unsolved riddle as those that he had before taken.

After his final exit, a rumor reached the settlement that Lewis had been a member of the ship’s crew of the notorious Captain Kidd, but at the time of his (Kidd’s) arrest in Boston, along with other members of the crew (and subsequently executed at London in 1701), Lewis, being then a mere youth, was given his freedom, with the understanding that more neck-stretching would follow should he continue the nefarious business of piracy. Not wishing to put the authorities to the trouble and expense of an additional execution he re-crossed the ocean and took refuge in the forests of New Jersey. It was also rumored that the stealthy journeys he had made from the settlement were for the purpose of bringing back and secreting treasures (the whereabouts of which he knew) that had been buried by Kidd and his rollicking cut-throat crew, along the Jersey coast.

The old settlers, according to traditional accounts, were firm believers in the reports that Kidd had disposed of much of his booty in this manner; and, as one writer has it, “Along every mile of the Atlantic coast in the United States his money has been dreamed about, and searched for, and the story of his—

Forty bars of gold,

And his dollars manifold,

As he sailed.and how he—

Murdered William Moore

And left him in his gore.

As he sailed.is a part of our nursery education.”3 Prompted by a desire to secure these buried treasures, a search of the Lewis [property] and other places in the vicinity was instituted. The log cabin of the old pirate was torn down, and every conceivable spot considered available for secreting his ill-gotten wealth was examined. The search was kept up for a long time but without success, and for the time being was abandoned. Perhaps it never again would have been resumed had it not been for the following circumstance:

It so happened that Othniel Gordon, above referred to, some years after the events described [probably in the early 1800s], while cutting a large tree near where the Lewis cabin had stood, discovered driven into its trunk, twenty or more feet from the ground, a huge iron spike that protruded one foot or more from the body of the tree.— Reasoning that this spike, found in such an out-of-the-way place, had been driven there as a marker by which to locate the hidden treasures, the search was renewed but with the same results as before. Not a florin could be found.

As is well known, most of the people living a century or more ago [late 18th/early 19th century] were firm believers in the supernatural, and as all earthly means had failed to discover the coveted treasures it was resolved to secure the services of a wizard or conjurer, then living in the Schooley Mountain region, who had the reputation through his magical art of being able to locate any place where was hidden stolen property, be its value of a farthing’s worth or the gold and silver bars and other valuables looted from richly laden Spanish galleons. An old writer described this august personage in the following manner:

“His perpetual brooding over dark and mysterious subjects aided in giving a countenance naturally far from prepossessing, a still more wild and unnatural expression. An artist desiring to personify superstition could not have chosen a better model. His long, lank form, bent and misshapen, his swarthy, lantern-jawed, unshaven visage, dark shaggy brows, a deep set, wild and wandering eye, which seemed ever and anon looking out for spectres, and then his costume—constructed with utter disregard to fashion, set off with a cap of colossal proportions rudely fashioned from the skin of some hairy animal, ornamented with its long, bushy tail, dangling over his shoulders, the whole forming as grotesque and singular and outline as the wildest imagination could conceive. And his manners are quite as eccentric as his external appearance.”4

The day of the arrival of this old worthy having been announced, he found as interested and excited a crowd awaiting him as can be seen at the present day in any country village awaiting the arrival of the circus and menagerie. In addition to his regular costume he carried in his hand a magic wand, or rod of iron or steel. Holding this mysterious implement in a horizontal position a short distance from the ground, he visited the different places pointed out to him where previous search had been made for the booty, meanwhile mumbling in a half audible tone some sort of jargon known only to himself and others of the fraternity who practiced his alleged magical art. Finally, at a certain place, the rod suddenly assumed a circular shape, each end resting on the ground. The old wizard then and there made this solemn announcement:

“That moneys and other valuables had been buried near this place, but a password had been used at its burial known only to those who were present at the midnight hour at which it was concealed, and if the person or persons who knew this mystic word could not be found, the treasures could never be recovered!”

That settled the whole business. From such a weighty decision as that there was no appeal. Disappointment was depicted on every countenance. Faith in the mystic rod was blasted, and hope for a season was crushed to the earth. In language not eloquent but emphatic (such as our grand-daddies could use when occasion required) the old wizard was told to take a vacation—go to the field where, in days of old, Nebuchadnezzar was turned out to pasture, there eat grass and grow wiser.

The old story of the pirate Lewis and his buried treasures is still often repeated, and some persons now living have an abiding faith in its truthfulness.

This is a wonderful story—perhaps something like this actually happened. However, I could not find any evidence for it . This is what I did find:

Hoppock wrote that the “premises now owned by Kensyl Reading” was at one time owned by a man named Ticnor Lewis, but there is no deed recorded for such a person. In fact (documentary fact, as opposed to “unwritten fact”), the land was owned by Dr. John Lewis, who acquired about 200 acres or more in 1727 from the original proprietary owner, Nathan Allen (who died in 1732).5 All of Sergeantsville north of Route 604 (Ringoes-Rosemont Road) was part of this 200 acres.

If this Ticnor Lewis turned up in Amwell not long after Kidd’s execution in 1701, then he was squatting on “unappropriated” land, and he would have had hardly any neighbors at all to observe his comings and goings, since settlement did not begin until around the time that Amwell Township was created in 1708. Nathan Allen did not purchase his proprietary tract until 1711.

Could he have been Doctor John Lewis of 1727? I wonder if “Ticnor” was a corruption of Doctor. Dr. Lewis did not live on this property all the time, so perhaps the comings and goings that Hoppock mentioned applied to him. He was living in Bucks County in 1716, and in Hunterdon Co., (probably Trenton) from 1722 to 1727. From 1733 to 1752 he lived in Amwell Township, then moved to Trenton in 1753, to New York in 1754 (where he was an engraver—if that John Lewis was the same person), and finally back to Amwell township by 1758 when he wrote his will.

Although I have called him “Dr.” John Lewis, in surviving documents he has a very different occupation. In 1716 he was a “Tinker.” In 1727, he was a “Tinker” in one deed and a “Brazier in another.” In 1752 he was of Trenton, “late of Amwell,” a “Brass founder” (although it’s possible this was his son, John Lewis, Jr., “a person of avaricious and wicked principle and Disposition”).

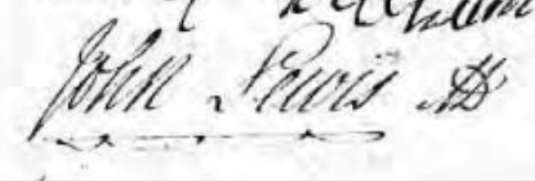

The first mention of John Lewis as a physician seems to be in 1745 when he witnessed the will of Andrew Heath of Amwell, and signed his name John Lewis MD—at least I think that’s what it says; decide for yourself:

He witnessed a few other wills during this time period, always with the same suffix. Then on Nov. 19, 1752, his name appeared in the account of John Thatcher of Kingwood, deceased as “John Lewis, Doctor.” In his own will of 1758, he gave no occupation; perhaps by then he was retired.

He witnessed a few other wills during this time period, always with the same suffix. Then on Nov. 19, 1752, his name appeared in the account of John Thatcher of Kingwood, deceased as “John Lewis, Doctor.” In his own will of 1758, he gave no occupation; perhaps by then he was retired.

Lewis died quite wealthy, more than a physician was likely to be. His inventory showed he owned £515 worth of personal property, and he owned land not only in Amwell, but also in Kingwood Township and in Trenton.

At some point, Dr. Lewis sold a part of his Amwell plantation on the eastern end to Garret Lake.6 Part of this property eventually came to be owned by Kensyl C. Reading.

In 1835, Dr. Lewis’ grandson, Benjamin Lewis, quit-claimed the rights of the Lewis family in the remainder of the old Lewis plantation to several purchasers: Jonathan Rake, John Gordon, Robert Rittenhouse, Henry H. Fisher, George Holcombe, Jacob Lake, John Fauss, Daniel Larew, Neal Hart, Isaac Scarborough, and John C. Bellerjean.

Since Jonathan M. Hoppock was born in 1838, these ‘aged citizens’ he was listening to were probably born in the late 18th century. And their “grandsires” would have been born about 40 or 50 years previously, taking us back to the 1730s or so. This gets us back to the time of Dr. John Lewis.

Charlotte Gordon was born in 1802, the second child of Othniel Gordon (1774-1862) and Mary Heath (1777-1851). Since Charlotte Gordon died in 1882, age 80, Hoppock must have been listening to her stories in the 1870s and the last two years of her life. Her parents lived on part of a 200+-acre tract purchased by Othniel Gordon’s grandfather, Thomas Gordon, in 1722, just north of the tract purchased by Dr. John Lewis. Dr. Lewis died in 1758, long before Charlotte Gordon was born, so the story she told had to have come from her parents, but even they were not born in Dr. Lewis’ time. We have to go back to Charlotte’s great-grandparents, the above-mentioned Thomas Gordon (c. 1697-1784) and wife Margaret Oliphant (1709-1784).

Hoppock wrote that in 1701, “Lewis [was] a mere youth.” That would mean he was born about 1680-1685. Once again that conforms to the age of Dr. John Lewis, who did not marry until around 1720.

Keep in mind that Othniel Gordon owned property adjacent to the Lewis/Lake farm, so he was trespassing when he was cutting wood. As for that spike in the tree, at twenty feet it was way too high off the ground to be used for hanging meat like venison, beef or pork. Very suspicious indeed.

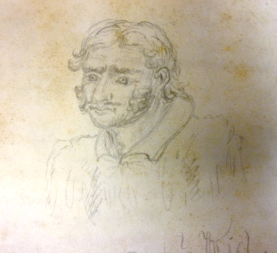

Captain Kidd was a figure of renown not only in Hoppock’s time but also in the 1690s. I know this because while doing some research into the West Jersey Proprietors a few years ago, I came across a portrait of him, sketched probably by the clerk taking minutes, probably about 1696, at the time Kidd was visiting New York. It is rather remarkable, and suggests strongly that the artist had actually seen Kidd in person. The picture makes Kidd look a little desperate.7

In England, Kidd looked like this:

In England, Kidd looked like this:

There is much more to the story of Dr. John Lewis and his son John Lewis, Jr. They will get a post of their own soon. But here is some more information about Charlotte Gordon and Kensyl C. Reading.

Charlotte Gordon

I have hunted for Charlotte Gordon in the census records, but only managed to find her twice. The first was in 1840 when she was living in Delaware Township and counted in the census as a head of household, in her 30s. Living with her were two other females, both in their 20s. They were probably her unmarried sisters: Nancy, who was born in 1810, and her youngest sister Eliza (born about 1815, married John German about 1840).

The only other census record I have found for Charlotte Gordon is in 1880, also Delaware Township. Then she was 78 years old (born c.1802) and single, living as a boarder in the Sergeantsville Hotel run by Isaiah Moore.

What is curious to me is that there was a “Charlotte Hoppock” in the 1860 census living with the family of Jonathan M. Hoppock’s parents, in Sand Brook, and she was the same age as Charlotte Gordon. She was not the sister of J. M. Hoppock’s father because Hoppock’s grandfather John R. Hoppock did not name her in his will of 1853. He did name his daughters Margaret and Mahala.

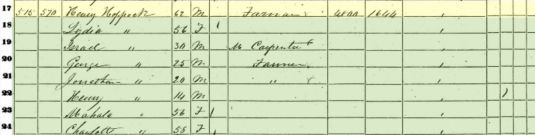

The 1860 census record for this family listed Henry Hoppock age 62, farmer; wife Lydia 56; sons Israel, George, Jonathan (age 20—our J. M. Hoppock), and Henry; also Mahala Hoppock age 56 and Charlotte Hoppock age 58 (born about 1802). Sadly, the 1860 census does not identify relationships. Keep in mind that enumerators would write the full name of head of household, and then use ditto marks for the surnames of the rest of the family. It is possible that the enumerator simply forgot to put in Charlotte’s surname, which would be Gordon, not Hoppock. I have found no evidence of a Charlotte Hoppock born c.1802.

When Charlotte Gordon died unmarried on August 14, 1882, Jonathan M. Hoppock was about 44 years old. She was buried in the Sand Brook Cemetery. Her sister Mary Gordon, wife of Jacob F. Buchanan, died one month earlier and is also buried there. But Charlotte was never counted in the Buchanan household. Their deaths preceded establishment of the Sand Brook (or Upper Amwell Baptist Church).8

When Charlotte Gordon died unmarried on August 14, 1882, Jonathan M. Hoppock was about 44 years old. She was buried in the Sand Brook Cemetery. Her sister Mary Gordon, wife of Jacob F. Buchanan, died one month earlier and is also buried there. But Charlotte was never counted in the Buchanan household. Their deaths preceded establishment of the Sand Brook (or Upper Amwell Baptist Church).8

On February 2, 1885, Charlotte’s executor, Jonathan H. Hoppock (1831-1915) submitted his account for her estate to the Orphan’s Court.9 Jonathan M. Hoppock and Jonathan H. Hoppock were only distantly related. And I can see no relationship between Charlotte Gordon and Jonathan H. Hoppock. Could this have been a typographical error, similar to the mistake made in the 1860 census?

Addendum 11/28/15: Charlotte Gordon wrote her will on April 17, 1870, when she was 69 years old. She left her wearing apparel and bedding to her sister Amy Gordon; also a bond & mortgage she held against Amy for her property, which was to be cancelled after Charlotte’s death. If Amy happened to die before Charlotte did, the wearing apparel and bedding was to be equally divided between the three daughters of Charlotte’s brother Thomas and Hannah Gordon, daughter of Franklin Gordon. She left $50 to her nephew John Gordon’s daughter Charlotte, “for a namesake.” The residue of her estate was to be equally divided between her sisters Amy Gordon and Parmelia Heath and her brother Franklin Gordon, and the heirs of Thomas Gordon deceased. The executor was named as Jonathan Hoppock, but when the will was recorded it was signed by Jonathan M. Hoppock, not Jonathan H. Hoppock, so I think we can take it that the newspaper notice of Dec. 3, 1884 in the abstract of the Gazette was in error. Witnesses of the will were A. J. “Ransaville” and Francis Heath.

Charlotte Gordon died on August 14, 1882. Her inventory was appraised by A. J. Ransaville and J. M. Dilts. It included the aforementioned apparel (worth $1) and bedding (worth $14.25). Also some silver spectacles worth $6. There was no furniture listed other than a chest and some crockery. She must have been living in someone else’s household. She did have significant wealth in the form of $53 cash in the hands of J. L. Jones as well as $6 in her own hands. Also notes against several people (Isaac Hoppock, J. W. Brewer, Mary Moon or Moore, D. W. Hoppock, and J. M. Hoppock). The total for all of this was $757.75. Then the doubtful notes were listed, against Samuel S. Bellis, Edward Housel, George D. Rittenhouse, and H. B. Nightingale, amounting to $817.16.10

Kensyl Reading

Kensyl C. Reading was named after his uncle, Kensyl Reading (1815-1900), son of Asher Reading (1784-1861) and Margaret Wolverton. This Kensyl married Hannah Risler in 1840 and had one or two children in New Jersey before moving to Iowa, about 1842. Reading Road was most likely named after his nephew, Kensyl C. Reading.

The name Kensyl is quite unusual, especially as a given name. I discovered that Margaret Wolverton Reading’s aunt was Abigail Wolverton, who married a John Kensell of Philadelphia in 1788. He must have made quite an impression for their niece Margaret to name her son after him. But why the change in spelling? There is a mystery.11

The Kensyl Reading that J. M. Hoppock was referring to was Kensyl C. Reading (C. standing for Cline), born November 18, 1863 to the brother of Kensyl Reading (Sr.), Samuel Wolverton Reading (1822-1873) and second wife LaReine Cline (1833-1903). Samuel W. Reading died a dramatic death in 1873 at the age of 50, as related in the Hunterdon County Democrat:

“Fatal Runaway Accident. On Wednesday morning last, Mr. Samuel R. [sic] Reading, of Delaware Township, was seated with Mr. Samuel Hartpence, the Rosemont undertaker, on a hearse, and were on their way to attend a funeral at Locktown. While going along, the young and spirited team they were driving took fright from the breaking of a spring of the vehicle and ran away, and coming in contact with a snow bank, both men were thrown from the hearse . . . Mr. Hartpence escaped with a few bruises, but Mr. Reading, besides other injuries sustained a fracture of the skull, from the effects of which he died on Thursday morning.”12

After Samuel W. Reading died, his widow married second Asa Cronce, in 1874. Cronce’s first wife was Margaret Reading (1828-1871), daughter of Asher & Margaret Reading, and therefore, sister of Kensyl Sr. and Samuel W. Reading. In the census for 1880, Asa Cronce was a 60-year-old farmer, wife Larenie was 44, keeping house, and daughter Ella was 23 single and at home. Also in the household were Jane Ent 18, servant, married during census year [I do not know who she married], John Hartpence 40, widower, working on the farm; and “mother-in-law” Margarette Reading age 93 (1787) widowed. Margarette Reading was mother-in-law to both Asa Cronce and LaReine Cline.

In 1880, Kensyl C. Reading (Jr.) was 16 years old, living with his widowed uncle, David Cline (also spelled Kline) in Kingwood Township, and attending school. In 1887, this little item appeared in the Hunterdon Republican:

Kensyl C. Reading, who has been absent for some time on a visit to relatives in Virginia, has returned home. He was accompanied on the trip by Mrs. Mary S. Fulper of Flemington and Mrs. Martha Lair of Mt. Airy.13

Both of these ladies were step-sisters to Kensyl C. Reading, being daughters of Samuel W. Reading’s first wife, Catherine H. Bodine, who died in 1856.14

I cannot say what he was doing in 1890, as there are no census records for that year. But on December 28, 1892, Kensyl Reading married Catharine Green, the daughter of Jacob L. Green (1827-bef 1910) and Elizabeth Hoff (c.1833-bef 1900). Jacob L. Green was the Sergeantsville blacksmith who later moved to Rosemont.

In 1900, Kensyl C. Reading was 36 years old (born Nov 1863) farmer, renting farm #79; wife Kate H. was 31 (born Jan 1869). They had been married 8 years, and had 2 children, Mildred F. 6 (Sep 1893) and Samuel A. 2 (Dec 1898). By 1910, he owned his farm in Delaware Township. The Farmers’-Businessmen’s Directory of 1914 states that his farm was 69 acres. The 1920 census listed him and his family living on the “Covered Bridge to Locktown Road.” One would expect that to be Pine Hill Road, but it could equally be Reading Road.15

Kensyl Reading was apparently an ingenious man. He stood out from his neighbors by installing a hydraulic ram, which provided running water to his house. According to Charles Jurgensen, the neighbors had to carry their water from their wells. Jurgensen wrote:

The Reading farmhouse was located on the southeast side of what is now Reading Road and not far from Green Sergeants, a one-room school where my sister Ebba taught for a number of years. The Readings had the luxury of having “running water” in their house when most people carried pails of water from springs or wells for domestic and animal use. This in itself was exceptional but not as exceptional as the hydraulic ram that was used to pump the water without the need for auxiliary power or the flow of gravity.

When my sister and I visited our Kendall School classmate, Lillian Porte Bernheisel, who lived near the Readings, we would stop to observe the ram operating and listen to the closing of the valves. Its operation was always a mystery and remained so for all the years we lived in Sergeantsville. When people were asked to explain how the ram functioned, the reply was either “I don’t know” or “it must be perpetual motion.”

Addendum, 9/15/2015: I just discovered an interesting article in the Trenton Evening Times, dated July 3, 1922, that tells us more about the springs on Kensyl Reading’s farm:

Sergeantsville, N. J., Dec. 2 [?] – Many farmers in this vicinity are completely out of water, due to the prolonged drought, and are compelled to haul the supply, for both household and farm uses.

Kensyl C. Reading of Oak Springs Farm, is supplying nine farmers from his famous spring, his neighbors hauling it away in barrels, both morning and evening, without any apparent diminution of supply.

No drought has ever reduced the quantity of water flowing from this spring to any material extent, although on a few occasions, when there has been a long dry spell in the early summer, the overflow at the upper spring, near his residence, has fallen some, but never enough to prevent him from giving water to all who needed it.

Several others are supplying water to neighbors, but so far as known, no one else in this vicinity is supplying anywhere near the same number of applicants.

This is particularly interesting in light of recent events, when the current owner, Charles Fisher, applied for permission to sell water from the springs. Concerns over traffic and pollution resulted in a denial of his application.

Kensyl C. Reading appears in the 1910 and 1920 census records for Delaware Township, but after that I lose track of him. I believe he died on December 29, 1946, age 83, but I do not have a source for that date. Ancestry.com family trees do not have his death date, or any census record after 1920. I have even less information on his wife Catherine.

Oh to be a time-traveler and go back to the days of Ticnor Lewis, whoever he was. I am grateful to Mr. Hoppock for telling us this story of a man who stayed out of the record books and might have been a pirate.

Addendum, 9/14/2015:

Kay Larson managed to find information on the family of Kensyl C. Reading that I had missed, quite a lot from the Trenton Evening Times. Putting it all together we have four children for Kensyl C. and Kate H. Green Reading:

- Mildred Fulper Reading, born Sept. 25, 1893, married Nedville Parkes of Lambertville. Marriage announcement in the Trenton Evening Times, Nov. 15, 1920. Nedville was the son of Horace and Marilla Parkes, whose farm was on land where the Delaware Twp. school now stands.

- Samuel Alden Reading, born Dec. 30 1898. An eighteenth birthday party was held at Oak Springs farm for Samuel Alden Reading, son of Mr. and Mrs. Kensyl Reading. (Oak Springs was their farm on Reading Road.) This appeared in the January 7, 1916 edition of the Trenton Evening Times, page five. A long list of guests is also given in the article. S. Alden Reading died in 1929 and is buried at Rosemont Cemetery, and can be found on Find-A-Grave.

- William Green Reading, born June 3, 1900 (mentioned in the 1910 census as age 10). He died in February 1987 in Bayville, NJ.

- Stanley K. Reading, celebrated his 18th birthday in 1916 at “Oak Springs Farm,” and who was mentioned as “on the sick list” in the Times of May 30, 1918. Kay thinks he might not have survived his father, but the obituary for Kensyl C. Reading states that he was survived by his widow, his daughter and his two sons, William and Stanley.

Kensyl C. Reading was 83 when he died, having been ill for five and a half years. The obituary noted that Mr. Reading was a long-time farmer, and had been a trustee of the Sergeantsville Methodist Church. It stated that Rev. Donald H. Gerrish of that church would preside at the funeral, held at the Reading home. Reading, was buried in the Rosemont cemetery, although he is not listed on Find-a-Grave.

Addendum, 9/25/15: A neighbor of the old Lewis property wrote to me recently, describing what he found when he walked down Reading Road: “Took a walk down to the elbow of Reading Road.” He found that “the stone springhouse [that is] visible from the road and more or less intact is not the structure shown in the photo” above. “The roof line, gables, and window placements are different. However, behind the springhouse and nearer the residence is a stone ruin, completely engulfed in vines and scrub, that lines up exactly with the residence house consistent with the photo. However, that ruin is on flat, dry ground whereas the springhouse sits atop a spring. The ruin might have been a smokehouse or a creamery. The oaks are gone, replaced by walnuts of varying sizes and shapes although there are massive, decaying stumps which could be remnants of the oak trees.”

Footnotes:

- I have written a little about the Williamson family in my article Pine Hill Revisited, and about the Sergeants in my articles on the Pauch Farm. You can find a little information on the Gordons in the Going, Going Gone article “Another House Lost.” ↩

- I do wonder if the description of Ticnor Lewis as “a blood-thirsty looking fellow, of a vicious and morose disposition, grotesquely dressed” might apply to John Lewis, Jr., who died in 1794 and seems to have been a much more unpleasant character than his father. The upcoming article on John Lewis will make that clear. ↩

- The poem was titled “The Dying Words of Capt. Robert Kidd, A noted pirate who was Hanged at Execution Dock, in England.” It was, first printed in London in 1701, and first printed in America in 1730. You can see the entire poem online: Capt. Kidd’s Lyrics. Interestingly, the American version of the poem dwells far more on the state of Kidd’s soul than does the British version. ↩

- What a shame Hoppock did not identify who this “old writer” was. ↩

- West Jersey Proprietors, Deed Book D, pp. 258, 259. ↩

- Recital, H. C. Deed Book 5, p. 67. The deed dated 1801 made reference to the will of Garret Lake Sr., dated July 30, 1787. It did not mention who Lake bought his farm from, but I know it was part of John Lewis’ plantation because of the metes and bounds described. The property was conveyed by Garret Lake’s son Garret Jr. to John Heath Sr. and amounted to 120 acres. ↩

- To my dismay, I find I did not record the book in which this picture was drawn. When I track it down, I will amend this post. ↩

- The earliest surviving gravestone in the Sand Brook cemetery is dated 1831 (for Delilah Rockafellow, wife of George Fauss). But the lot for the graveyard was not conveyed to the Sand Brook Church until 1849, by Hiram and Amanda Moore. Charlotte’s father, Othniel Gordon, died too early to be buried in the Sand Brook Church cemetery, so he was buried in the Rake cemetery nearby. His wife Mary could have been buried in the church cemetery, as she died in 1851, but it makes more sense that she would be buried next to her husband in the Rake cemetery. ↩

- Hunterdon Republican, 12/3/1884. There was no other notice of Charlotte Gordon in either this paper, or in the Hunterdon Gazette or the Hunterdon Co. Democrat. ↩

- Wills, Book 13, p. 782; Inventories, Book 19 p. 96, Hunterdon Co. Surrogate’s Court. ↩

- Abigail Wolverton was the daughter of Maurice Wolverton (1730-1770) and Margery Baker. She and husband John Kensell lived in Philadelphia and in the town of Plymouth in Montgomery County, where Abigail Wolverton died in 1821 and John Kensall died in 1828. Their graves can be found on Find-a-Grave. ↩

- Hunterdon Co. Democrat, April 1, 1873. ↩

- Hunterdon Republican, Nov. 23, 1887. ↩

- Exactly why these three would spend time in Virginia is a question. I presume there was a relative living there, but I have not identified who that was. ↩

- I could not find him in the census records of 1930 or 1940. ↩

Kay Larsen

September 12, 2015 @ 7:51 am

Your death date for Kensyl C. Reading is correct. His obit appeared in the Tuesday, Dec. 31, 1946 edition of the Trenton Evening Times. He was 83 according to the obit. (genealogybank.com)

Bob Fusi

December 4, 2015 @ 7:34 pm

Do you have any more information on Isaiah Moore running the Sergeantsville Hotel in 1880? All I could find in my research on the Moore family was that he owned it from 1840 to 1842. (from an article in Living Places on the Sergeantsville Historic District)

Marfy Goodspeed

December 6, 2015 @ 7:49 am

Isaiah A. Moore (or Isaiah H. Moore) is a quandary. He married Mary, the daughter of Cornelius Lake, in 1837, and died either in 1885 (N.J. Death Records) or 1886 (obit in the Democrat). He appears to have spent his entire life in the neighborhood of Sergeantsville. I’ve got a long list of Moore’s who might have been his parents, but haven’t been able to identify which couple it was.

Bob Fusi

December 6, 2015 @ 5:36 pm

There was an Isaiah , brother of Hiram and Rhoda Moore (who married Albertus Wagner) .His father was David who in his will (d 1843), absolved Isaiah of a debt of $2300 that he had borrowed to purchase the Sergeantsville Inn.

Marfy Goodspeed

December 6, 2015 @ 6:45 pm

Ah-hah! I did not have David’s will. That’s a pretty good clue. I see that my problem is that sometimes he was called Isaiah A. Moore, and sometimes Isaiah H. Moore. It was the latter in his father’s will. Thanks to Ancestry, the will can be read online: “to my son Isaiah H. Moore a certain bond that I hold against Levi Chamberlin for the sum of $1150, secured on land in the twp of Amwell, or the sd bond may be assigned to him by my Executrix at the option of sd son; and I exonerate him from payment of all money that I have advanced to him for the payment of the Sergeantsville Tavern amounting to $2300.”