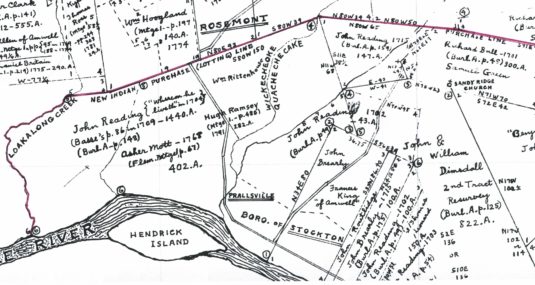

Not long ago, Dennis Bertland inquired about an old house that might have been located on the William Rittenhouse tract that I recently wrote about (“The Rittenhouse Tavern.” Dennis’ inquiry can be found in the comments section.) It is located in a blank space on the Hammond Map between the Wickecheoke Creek and Shoppons Run. Who did that space belong to?

As you can see, Mr. Hammond placed Rittenhouse to the north of the Wickecheoke and John Reading to the south of Shoppons Run, and left a blank space in between. I had no idea who owned that space. But while working on this series of articles about Rosemont I was digging around in my old files and came upon a survey map that had the answer.

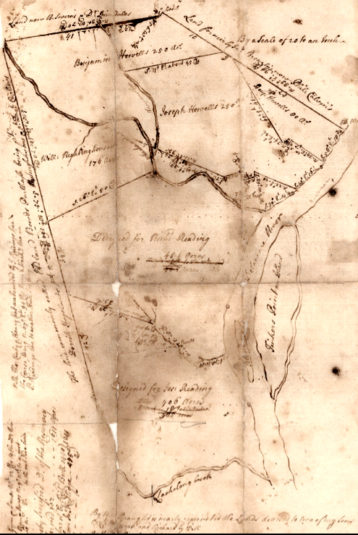

The 1744 Survey Map

The map was drawn in 1744, and pretty thoroughly settles the question. That house on the north side of Shoppons Run was part of Benjamin Howell’s property. (Click to enlarge.)

The map was drawn in 1744, and pretty thoroughly settles the question. That house on the north side of Shoppons Run was part of Benjamin Howell’s property. (Click to enlarge.)

First, I must give credit where it is due. The map is held by the Bucks County Historical Society.1 It was found by Dave Reading when he was doing research for his study on the Howell-Rittenhouse Cemetery. I consider it a marvel and a treasure.

Next, please note that the map is oriented toward the east-northeast, rather than the north. The tract begins on the Delaware River and runs north along land of Philip Calvin, then north along land of B. Severns and Dr. Dimsdale to the Lotting Purchase line, then southwest along that line to the Lockatong Creek, then down the creek to the river, and along the river to the beginning. It does not seem to include Bull’s Island (which has a different name).

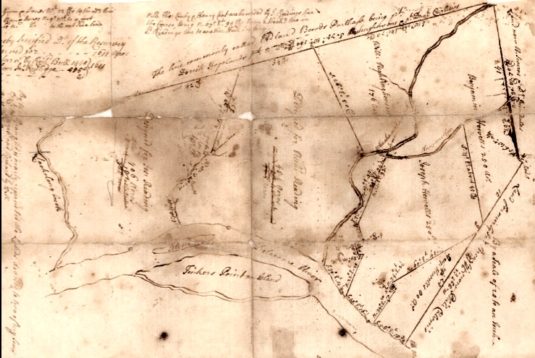

Here is the map rotated to the right to show the writing at the top. The notes are hard to read, but one of them states that this is a resurvey of a survey made by Richard Bull for 1611 acres, meaning I suppose that it includes other properties that John Reading acquired after his purchase of 1440 acres.

The west half of the tract was given to Joseph and Richard Reading, the sons of Gov. John Reading. Joseph Reading got the far west portion bordering the Lockatong Creek. Richard got the other half. The straight line dividing Richard Reading’s land from that of William Rittenhouse is the course of Route 519 on its way up to Rosemont. The Rittenhouse tract is bordered on the south and east by the Wickecheoke Creek.

The west half of the tract was given to Joseph and Richard Reading, the sons of Gov. John Reading. Joseph Reading got the far west portion bordering the Lockatong Creek. Richard got the other half. The straight line dividing Richard Reading’s land from that of William Rittenhouse is the course of Route 519 on its way up to Rosemont. The Rittenhouse tract is bordered on the south and east by the Wickecheoke Creek.

The eastern half of the Reading tract became the Howell Tract, which includes Prallsville and Stockton. It is curious the way property assigned to Benjamin Howell has to surround the tract for Joseph Howell. Part of the reason for that was an attempt to fairly share the river frontage. The third Howell property, much smaller than the others, is on the east side of the Wickecheoke and will be discussed below.

My only quibble with this wonderful map (besides being so hard to read) is that the map does not show the location of Route 523 in relation to the Howell properties. That becomes important later on. However, if you zoom in on the map to follow the line between Benjamin and Joseph Howell, starting at the river, you will see a sort of dog-leg around a square. I’m pretty certain that represents the old Howell Tavern, now the location of the lovely white church on Route 523 on the north end of Stockton. The diagonal that proceeds northeast from there along land of John Brearly and Philip Calvin is probably the route of 523 from that point.

My suspicions were confirmed when I read this from a conveyance dated December 23, 1749, from John Reading to Joseph Howell. It concerned

“a certain Messuage, Tenement, Plantation or tract of land in Amwell beginning at the middle of the ferry road by the Delleware River side being the boundaries of his brother Benjamin Howell’s land from thence along the boundary thereof being part along the middle of the Road as it now is used”2

That “ferry road” that begins at the river is Ferry Street today, in Stockton. It ends at the intersection of Route 523 and Route 29. Originally, Route 523 began at the river and went inland to the tavern house before climbing the hill above Stockton.

Purpose of the Map

In order to understand why the map was made, we must study the early history of the Reading family of Amwell. As I have written before,3 John Reading had 1440 acres surveyed for him shortly after the negotiations for the Lotting Purchase were concluded in 1703. Reading himself was one of the negotiators and surveyors for the 150,000-acre “Lotting Purchase” from the Indians. I have little doubt that Reading realized while surveying the area that land bordering the Delaware River, at the point where the river takes a turn to the west, was an ideal location, given the view it provided of traffic moving up and down the river.

Shortly after the survey was made and the land transferred, Reading and his family settled on this property, and shortly after that, in 1708, the Township of Amwell was created, no doubt at Reading’s suggestion. The township was named after Reading’s property, which was called Mount Amwell.

Reading built his house on the section of the survey labeled Richard Reading, John Reading’s grandson. John, Sr. died in 1717 leaving only one son and one daughter. The daughter, Mary Else, married Daniel Howell around 1710 and had at least six children. The son, John Reading, Jr., later to be known as Gov. John Reading, married Martje Ryerson and had 11 children.

John Reading, Sr. died intestate in 1717. With only two children to survive him, his property was divided in half. The traditional story is that John Reading, Sr. gave a square mile of land to his daughter Mary and son-in-law Daniel Howell when they married. But we do not know exactly when they married. There is no recorded deed to verify this gift; all we have is the recital mentioned above. So I am not entirely certain if Reading, Sr. gave this land during his lifetime, or if the division of his tract took place after this death.

In my article on the Rittenhouse Tavern, I speculated that William Rittenhouse got his property from Daniel Howell, his brother-in-law. That may have happened as early as 1719, following the death of John Reading, Sr., when his son and administrator of his estate, John Reading, Jr., made a confirmation deed dated February 20, 1719, conveying the original gift of land to Daniel Howell.4

But why 1744?

The answer comes from this deed, dated 1794, in which Charles & Ann Wolverton sold the mill property at Prallsville to John Prall, Jr. One of the most important features of recorded deeds is the Recital which explains how title to the property came into the hands of the grantor. Every once in a while, you’ll come across a Recital that goes back a very long way. The Recital in this deed includes this:

. . . certain lots or tracts of land that was originally conveyed by John Reading to Daniel Howell by a deed bearing date the 20th of February 1719 which deed at the request of the said Daniel Howell was made null & void by the said John Reading and a new deed bearing date the 15th day of February 1744 given by John Reading to Daniel Howel & John Howel son to the aforesaid Daniel Howell

In order to file a new deed on February 15, 1744, a survey was necessary, to delineate property belonging to the Readings and the Howells. The survey was made by John Reading, Jr., who had learned the profession from his father. By 1744, both John Reading, Sr. and Daniel Howell, Sr. had died, and their grandchildren had reached adulthood. It was time to clarify who got what.

Daniel Howell, Jr., the eldest son, was born around 1718, so by 1744 he was 36 years old. The youngest son, Benjamin, was born in 1725, so he had just reached adulthood by 1744. That was probably the most important reason for creating a new deed and a new survey.

The Howell Family

Daniel Howell, Sr., yeoman of Amwell, wrote his will on September 9, 1733, when he was only 46 years old. Living in the wilderness was dangerous. Daniel had been running a ferry, a tavern, and a grist mill. He also ran a copper furnace. Any one of those activities could have been the death of him. At least it was not sudden, as he had time to write a lengthy will. He did not include his wife, Else Reading, because she had predeceased him, dying on February 27, 1732.5

Daniel Howell named his brothers-in-law, John Reading and William Rittenhouse [spelled Rightinghousen] to be his executors. But the will was witnessed by people who were 1) not related to him and 2) did not even live in his neighborhood, which I find curious. They were Samuel Fleming, Frances Mason and Walter Cane. (Frances was actually Francis.)

After bequeathing several items of personal property, Howell ordered that income from his mill and his plantation should be used for the “maintenance and bringing up of my Children in their minority.” After which he made these bequests:

– to sons Daniel and John the Cornor Grist Mill and the Land and Geers and Utensols thereunto belonging, Together with 60 acres of Land to be taken from the upper side of the farm or plantacon whereon I now dwell fronting upon ye river so far down the same til a line from thence will include half of ye young orchard by the Barn and to run the sd Course to the next Hollow from thence (if it can be a straight line) to the rear of the Tract saving always the Improvements to the old farm; and also the liberty to lead the water in a Dich or otherwise form the present water course to suit their own conveniency, as tenants in Common and not as Joynt Tenants6

– to sons Joseph and Benjamin the remaining part of the plantacon whereon I now dwell with the buildings, improvements, to be divided between them share and share alike as Tenants in common and not as Joynt Tennants;

– to daughters Elizabeth and Mary all the Tract of Land at Aliaschokkin in Amwell with the Improvements to be divided between them share and share alike as Tenants in common and not as Joynt Tennants;

The land left to daughters Elizabeth and Mary on the Aliaschokkin [Alexauken?] Creek in Amwell township was not part of the Reading tract.

As one can see from the survey map, Daniel Howell divided most of his Amwell property between sons Benjamin and Joseph. It is hard to see on the Survey, but, according to the will he also gave a much smaller tract to sons Daniel Jr. and John. This may seem unfair, but the smaller tract was more valuable as it contained a grist mill, which was apparently even more profitable than the tavern and ferry, which were part of Benjamin Howell’s share.

Since the subject of this article is the house on present-day Worman Road, let’s stay with Benjamin Howell, the property owner in 1744.

The House

Dennis Bertland mentioned in a follow up email that the property had been included in the County Historic Sites inventory, and identified as “Howell Dwelling.” They certainly were right about that, since the house is located on the land between Shoppons Run and the Wickecheoke—in other words, it belonged to Benjamin Howell.

What else do we know about the house? Since it has not yet been examined by an architectural historian, we must rely on the description in Hunterdon County’s “Sites of Historic Interest,” prepared in November 1979 as part of the County Master Plan. Here is what it has to say about the house on Block 33 Lot 8.01:

Howell Dwelling. This is a stone, deep form, five bay (three bay and two bay unit) dwelling with a two bay, slightly higher, frame extension.

This tells us little. But Dennis Bertland, who has only viewed the house from the road, believes that the fenestration, the dimensions and other clues suggest that the house could have been built as early as the mid-18th century, and as late as the early 19th century. And he is inclined to think it was earlier rather than later. Obviously a much closer inspection will be needed to properly date the house, but this assessment suggests that it could have been built by Benjamin Howell himself, since he married in 1755.

Benjamin & Agnes Woolever Howell

Benjamin Howell was born in 1725 and married Agnes Woolever about 1755. She was the daughter of Jacob Woolever (1701-1774) and Maria Elsabetha Schwitzeler. The couple had only two children—sons Jacob and Joseph.7

It is odd and rather curious that Daniel Howell mentioned and specifically bequeathed his grist mill (to Daniel & John) and his copper furnace (to Joseph and Benjamin), without any mention of the ferry or the tavern. Once again, the mill and the furnace must have been the income-producing properties, while the ferry and tavern were less important. But both ferry and tavern continued in business.

In 1746, Gov. John Hamilton granted Benjamin Howell a patent for running a ferry over the Delaware River from Amwell Township “at the mouth of a Spring of water about a quarter of a mile a little more or less below a grist mill on a stream of water commonly called in the Indian Language Wickecheoke.8 In 1761 he leased the tavern house to John Horn. He probably leased both ferry and tavern to other people unknown up until 1785 when he leased them to his son Joseph Howell [Jr].

In 1774, Benjamin Howell and John Ely, miller, had to come to an understanding about the borders of their properties. John Ely had acquired the mill lot. According to a deed of May 19, 1774, for £50 Ely conveyed to Benjamin Howell whatever rights he might have in an area of about three-quarters of an acre that infringed on Howell’s ferry lot, with the dividing line running through “the new part of Howell’s mansion house.”9 There was a long and interesting description in the deed, including a stipulation that Ely would not establish a ferry on his own property.10

Another interesting document, undated, was found in the Austin Davison Papers at the HCHS. It was a lease from Benjamin Howell of 83 acres out of his 250-acre farm to his son Joseph Howell. The rent was in the form of three-quarters of the harvest off that 83 acres, while Benjamin Howell undertook to pay for seed and teams. Joseph Howell was also to pay the “land tax” whenever it was demanded. The penal sum for nonperformance was £50, to begin March 9, 1782.

Is it possible that Joseph Howell built himself a house at this time? Yes, but Joseph was just 20 years old. He married about 1785, so he certainly could have been the builder. We need more information.

Unlike his father, Benjamin Howell died at an advanced age. He was 70 when he died in 1795.11 Also unlike his father, he was not prepared for his death—that is, he failed to write a will. [Added 10/2/18] Actually, there is a reason for that. Benjamin Rittenhouse is said to have died from a rattlesnake bite.[#. This comes from a “Brief History of Stockton” by Austin Davison in 1964. I do not know what Davison’s source was for this story.] His widow Agnes renounced administration of his estate on October 24, 1795 in favor of her two sons, Jacob and Joseph, “being the only children left by Benjamin Howell dec’d.”12

If only he had written a will. It probably would have given us some idea of where Benjamin and his two sons were living in 1795. Since he died intestate, his property was divided between his sons Jacob and Joseph. And here is where I run into trouble. I have no survey map for 1795 to show me exactly who got what. So I must review the histories of both sons to find what they owned.

* * * * *

Dear Readers,

This is not where the original article ended. In the previous version, I had gone on to write about Benjamin and Agnes’s son Jacob. But in the process of researching the two sons Jacob and Joseph Howell, I discovered that I had come to the wrong conclusion about who inherited the Howell house. I thought that Jacob’s property did not include the house, but it turns out I was wrong. I ignored some of the advice I offer when giving talks on how to do a house history. Rule One: examine everything. Rule Two: plot every deed. Rule Three: if you feel uneasy about something, keep researching until who feel sure you are right.

It was Rule Three that made me go back and look at my research more carefully, and to do more of it. Now I have a very different story to tell, and will save it for the next article, The Howell House, part two.

Footnotes:

- Hunterdon County Land Drafts, MSC 163 F1, Spruance Library. Also, the copy is a little fuzzy. It was my hope to obtain a better copy before publishing this article, but alas that was not to be. If I do get a better copy, I will certainly replace this one. ↩

- Recital, Deed Book 2 p 39, George Ely to Joseph Ely. ↩

- See John Reading and the Creation of Hunterdon County, parts one and two. ↩

- Recital, H. C. Deed Book 2 p. 35. ↩

- Birth and death dates for Mary Else Reading were found in the family bible of John Reading, Jr., photocopies of which can be found at the Hunterdon Co. Historical Society, the NJ Historical Society, the Genealogical Society of NJ, and the Pennsylvania Genealogical Society. The original bible was owned at one time by Hiram Deats in 1929, and he was the one who made the photocopies. He later donated the book to the NJHS, but it has not been found. This information was provided to me by Dave Reading. See also The Howell Family Tree. ↩

- Just a reminder for those not familiar with terms used in real estate law—Tenants in Common were not tenants as we know them today, they were landowners who shared ownership of the property, but each could independently sell their share, whether half, a quarter, or whatever. Joint Tenants could not do that. They shared one undivided interest, so if a sale was made it had to be by all of them together. ↩

- Josiah Granville Leach, Genealogical and Biographical Memorials of the Reading, Howell, Yerkes, Watts, Latham and Elkins Families, Philadelphia, 1898. ↩

- NJ State Archives, “New Jersey Commissions,” Book AAA p. 265. ↩

- Why the old line ran through the house is a question I attempted to answer in “A House Divided.” ↩

- NJ State Archives, Deed Book AK p. 607. ↩

- Agnes Howell died, on September 29, 1820, age 86 years and 2 days. She was buried in the Howell-Rittenhouse Cemetery. The date and age come from her gravestone. Benjamin Howell was also buried in the Howell-Rittenhouse Cemetery. ↩

- Abstracts of Wills, NJ Archives #1717J ↩

Dennis Bertland

September 23, 2018 @ 11:13 am

Another wonderful article Marfy peeling back the layers of local history. The 1744 survey certainly is the Rosetta Stone for understanding the early historical development of the Stockton/Prallsville neighborhood. If I am not mistaken the words “mill house” appear on the map, partially obscured by fold wear, near the mouth of Wickecheoke Creek, just west of the jog in the property line between the mill lot and Joseph Howell’s lot to accommodate the Howell-Rittenhouse graveyard. I also was intrigued the directives in Daniel Howell’s 1733 will that the mill lot was to include 60 acres taken from the upstream end of the farm on which he then lived and that the line delineating it was to be drawn to include half the young orchard by the barn and “saving always the improvements to the old farm.” This language strongly suggests that in 1733 Daniel Howell’s homestead was located on the property surveyed for his son Joseph in 1744, apparently near what is now the Prallsville Mill complex, a likely candidate for the site being the farmstead on the crest of the hill, now The Wolverton Inn. Were the “improvements of the old farm” distinct from his 1733 residence, perhaps located on what became the 60-acre mill lot?

Looking forward to the next episode.

PS. Loved the name for Hendrick’s Island, the large island in the river opposite the mouth the creek: “Tinkers Point”

Dennis Bertland

September 23, 2018 @ 2:42 pm

One additional thought. In the division of Daniel Howell’s property in 1774, son Benjamin received considerably more land (80 additional acres) than son Joseph in the division of the property that was to be shared by the two brothers, which might be explained by Joseph’s share including their father Daniel’s homestead, while Benjamin’s share encompassed the presumably less valuable Ferry house, located within the jog in the line between the brother’s river-front lots

Marfy Goodspeed

September 23, 2018 @ 3:22 pm

That makes sense.

Doreen Grieve

September 24, 2018 @ 2:49 pm

Happy Birthday and thank you for another so interesting and well researched article!

RD Scally

November 24, 2019 @ 8:14 pm

Extremely interesting series. I’ve seen this home and the briefly mentioned ruined barn close up. On the northwest corner stone of the barn the date 1714 is inscribed, which may helped date construction of the original portion of this house. The ruined barn is a banked style two-level stone barn that was most likely built by skilled masons given the quality and style of construction. An old quarry is located along the south side of Worman Road a few hundred feet to the west of the house & barn. I have a photo of the barn corner stone with the date, BTW.

Marfy Goodspeed

November 25, 2019 @ 8:08 am

Thanks! That bit of news about the datestone is most interesting. It confirms my opinion about it being a Howell house. In 1714, there was hardly anyone in the neighborhood except Readings and Howells.

RD Scally

November 26, 2019 @ 7:20 pm

Oops. My bad. It’s apparently 1712. So a couple of years earlier still.