This year residents of Delaware Township in Hunterdon County celebrate the 175 years since the township was created. The story of how this came about is a surprising one, and a little disheartening.

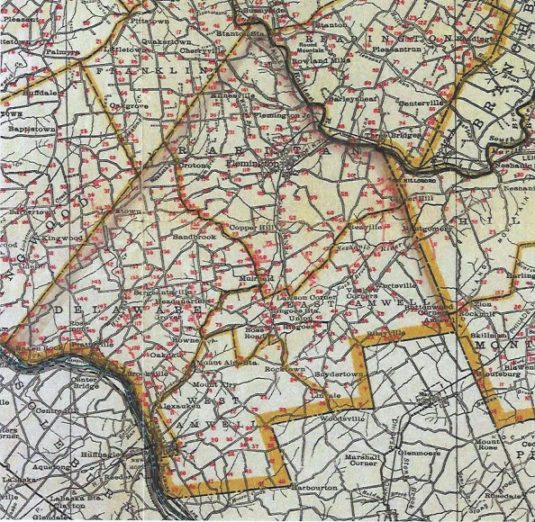

On February 27, 1838, the people who lived in Delaware Township, Hunterdon County called themselves residents of Amwell Township. That’s what they had been ever since 1708 when Amwell Township was created at the behest of John Reading, one of its earliest residents. Amwell was a huge township, compared to the other towns in Hunterdon County—128 square miles, a good three times larger than the other towns, with three times the population. It consisted of present-day Raritan, Delaware, East and West Amwell, Lambertville, Stockton and Flemington.1

On February 28, 1838, Amwell residents were astonished to read in the Hunterdon Gazette that the state legislature had divided Amwell into three new townships, without bothering to get the opinion of its citizens.

The act followed by one day the creation of a new county called Mercer, which consisted of towns in old Hunterdon like Lawrence, Trenton, Ewing and Hopewell, and parts of Somerset, Burlington and Middlesex. It was named for Revolutionary War General Hugh Mercer, who died during the Battle of Princeton.

Much wheeling and dealing was required to establish this new county. Part of the deal was division of Hopewell Township between Mercer and Hunterdon Counties, and another part was division of Amwell into three new townships. The legislators even took it upon themselves to name the new towns: Raritan, Delaware and Amwell. The new Amwell Township was to include today’s East and West Amwell, along with Ringoes and Lambertville. Stockton was still a part of Delaware Township, and Flemington was still part of Raritan.

Because the news came so suddenly, it was not well received. People had been expecting the creation of the new county of Mercer for a few months. Meetings had been held for and against it, but by January 1838, it seemed clear that the new county bill would pass. In the elections of the previous fall, Whigs had gained control of the legislature, and they wanted more representation. Trenton and the towns surrounding it all had Whig tendencies, so it made sense to put them together into a new county.

Upper Hunterdon, that is, Hunterdon as it is today, was none too happy about that, being more agricultural and decidedly more Democratic. In that election in the fall of 1837, Hunterdon had split its vote between the two parties according to geography. Five townships had voted for the Van Buren or “Caucus” ticket: Kingwood, Alexandria, Tewksbury, Reading and Amwell. By far the most Van Buren votes were cast in Amwell. The opposition Whig ticket won in Trenton, Ewing, Lawrence, and Hopewell, but also in Lebanon and Bethlehem.

So although it seems obvious and simple that most of the Whig towns could be formed into a new county, the problem was representation in the state legislature. The constitution of 1776 was still in effect in 1838. It provided that there would be one member of Council from each county. So the new county would mean a new member of Council, who would almost certainly be a Whig. The Council of the state legislature was somewhat equivalent to today’s State Senate.

The Constitution allowed the Assembly to decide how many delegates each county could send, as long as there were no less than 39 members. Old Hunterdon had 5 members of Assembly. But when the new county was first proposed, Hunterdon was to keep 5 members and Mercer would have 4. This did not sit well with some of the other counties.

The new Hunterdon would have a population of about 24,000 people, which was supposed to entitle it to 4 members, and Mercer would be entitled to 3. But after negotiations, Hunterdon was reduced to 3 members and Mercer only got 2, thereby maintaining the same number of members overall (the original 5), and giving a slight advantage to Hunterdon. However, the Whigs were now certain that 2 out of the 5 members from the old Hunterdon district would belong to their party.

On February 7th, the Hunterdon Gazette reported that the bill for a new county passed the Assembly. It included a controversial provision that divided Hopewell Township between Hunterdon and Mercer. On February 22, the bill passed the Council, but the Council member from old Hunterdon declined to attend the session.

This was a little surprising because the Hunterdon Council member was a Democrat, and, according to the New Jersey Gazette, the division of Hopewell was made at the request of “Van Buren men” in northern Hunterdon. Perhaps the problem was that this member of Council, Joseph Moore, happened to live in Hopewell. Joseph Moore must have felt just as divided as his township actually was. He was a Democrat, from a Whig township. Hopewell voted against him in 1837, giving him only 148 votes, while his opponent, Henry S. Hunt got 374. In Amwell, on the other hand, Moore got 730 votes while Hunt got only 486. It was Amwell that got Joseph Moore elected.

Meanwhile, on February 28, 1838, the Hunterdon Gazette announced the following item:

“MORE DIVIDING– The legislature, in their wisdom, have deemed it proper to divide the township of Amwell into three—A line from the mouth of the Ellisocken to the York Road near Mount Airy, thence along said road to Greenville [Reaville] leaves Amwell to the south.–Then the road from Ringoes to Quakertown makes the line between the township of Delaware on the west and Raritan on the east of said road. So we are informed. And all done, not only without giving the people the trouble to petition for the measure, but without even letting them know that such a measure was necessary to their convenience. We like such promptness—it shows a going-ahead spirit.“

The law did not take effect until April 2, 1838. During the month of March, the people of Amwell had a chance to react, which they did. We can’t know what everyone thought, of course, but the letter-writers made themselves abundantly clear. Two letters appeared in the Hunterdon County Gazette for March 14th, 1838 that expressed the outrage felt by the “Citizens of Amwell.” One of those letters stands out for its clarity, but also for its hints of skullduggery:

“Mr. Editor: – ‘There is a time when forbearance ceases to be a virtue;’ – when the voice of public liberty cries for redress at the hands of an enlightened and generous community. That time has been ushered in at a moment when the rights of the people seemed secure and unassailable. The recent transactions of our state legislature, to whom we are accustomed to look for the preservation of those sacred bonds that hold us together, cannot evade the scrutinizing eye of public justice.

“It is well known that the divisions of the township of Amwell, marked out by a few designing and interested individuals, and ratified by our legislative body, is [sic] a vital thrust at the rights of the people, and as such must incur the indignant sentence of public disapprobation. If the hallowed principles upon which our government is founded are to be thus violated with impunity, and our necks to be fettered by the iron chains of a few would-be patriots, then good night to liberty.”

And further on, “We feel conscious that the sanctity of our authority has been treated with contempt, in the division of our town-ship; that our right of representation, which we claim as ‘inalienable,’ has been clandestinely embezzled by dishonest ‘men and measures,’ and our constituents gulled into enactments as pernicious as they were rash and precipitate.

“We therefore feel that we have been aggrieved – that laws have been created with reference to us which are altogether unwarrantable, and palmed upon us with as little ceremony as if we were a race of slaves. Is it not a just cause of provocation when our rights are trampled under foot without our consent, and even without our knowledge? And must individuals ‘clothed in a little brief authority,’ and to subserve themselves, secretly adopt measures to split up our township by practicing deception upon a too-confiding legislature?

“It is an injury to which we cannot tamely submit – we cannot submit to see our property and that of our neighbors depreciated, without an appeal to such means as will reinstate it to its original valuation. And how is this to be done? Is it to proceed demurely to organize ourselves in the respective townships in which we have been most strangely juggled together, and bow in servile submission to the legerdemain of tyrants in miniature? Or must not such pernicious enactments rather meet with their doom in the virtuous indignation of a free people, who are as incapable of servile sub-ordination as they are of political intrigue. [signed] CITIZENS OF AMWELL. Ringoes, March 6, 1838.”

Methinks the writer was a Democrat, but who it was I cannot say. It was the usual practice in those days for people writing to the editor of a newspaper to use a pseudonym. Perhaps it was because politics was so ‘up close and personal’ then that people needed a little space to express their opinions. This letter shows how much more literate the Citizens of Amwell were than we are today. The passion of this writer rings like a bell.

Things would have been even more interesting if the Hunterdon County Democrat had been in business, but that paper did not start publishing until September 1838, too late for this story. The Democrat was a very partisan paper, as its name suggests. The Gazette, under editor Charles George, purported to be neutral, but George was in fact a Whig, and his sympathies showed in his editorial column. Had the Democrat been covering this issue, there would have been fireworks in Hunterdon County.

For the conclusion of this story, see Division, part two.

Footnote:

- Five years ago, in celebration of its 170th anniversary, I published a series of articles on the website “The Delaware Township Post.” It seems appropriate to republish those articles this year on my own website, slightly edited. ↩

Roger Harris

January 22, 2013 @ 8:37 am

I just went through this updated version and enjoyed it as much as before. I had always envisioned the creation of our Delaware Township as a joyous event, complete with bands, bunting and parades – dancing in the streets (the Skunktown Shuffle of course). But instead it was pure political gerrymandering.

But, despite the unhappiness of some in 1838, 175 years later I think that Delaware has become a very natural township. (We lucked out in that respect). Sergeantsville, the center of town, is – in fact – in the center of town. Unlike, for example, Ringoes in relation to East Amwell or West Amwell [where’s the “center” of West Amwell?] or center-less Raritan. Sergeantsville is at a crossroads, our school is in the center of town, churches are in the center of town, government, post office, general store, Inn etc. The outlying hamlets only add to the cohesion, I think. And on top of all that, we have one of the most beautiful town halls in the State.

I’m glad that you explained the political leanings of Gazette editor Charles George. When I read his announcement of Feb 28, I thought it was pure sarcasm (“The legislature, in their wisdom…” and “We like such promptness…”).

Interesting too that it was common practice for authors of letters-to-the-editor to use a pseudonym. Today we don’t really approve of that kind of thing – insisting on more honesty and transparency.

Looking forward to the next installation.

Marfy Goodspeed

January 22, 2013 @ 9:21 am

Roger, thanks for pointing out that despite its awkward beginnings, Delaware Township is a wonderful place to live, and despite its arbitrary boundaries, is a very cohesive, well-defined place. It’s nice to know we can rise above politics and really have something to celebrate.

Pete Kinsella

February 10, 2013 @ 1:49 pm

Marfy,

Enjoyed your story immensely, I’ll pass it on to our current representatives in Raritan, if you don’t mind’

Two further items. We have our first Twp. minutes from April 9th, 1838. Beautiful penmanship( of course!) and extremely succinct. There is mention of Delaware in the remarks. We will read them at the Delaware Twp. Commemoration in early April. Also, we have posted two historic markers at the eastern border (the 1688 Province Line) of Raritan Township. One is at the extremely busy intersection of Clover Hill Road and Amwell Road, the other on Hillsborough Rd. ( seldom traversed) running along the South Branch at gthe County Linr. You might enjoy them.

Thanks,

Pete

Secondly, As you travel

Donna in Las Vegas

April 7, 2013 @ 4:54 am

Seeking information on an endangered property whose future looks bleak. My Brother passed away recently,I will soon be visiting Hopewell to settle his estate. I was shocked to discover that the property UNDER his home has been purchased by Merrill Lynch,and they plan to destroy all of the structures as soon as I remove his personal items from the house. This just can’t be right! This is not about money(for me-)It’s about putting the brakes on this so I can buy some time to investigate. My Brother’s name is Bruce Smith and he lived in the old farm house on Scotch road, directly across from the massive M.L.”CAMPUS”. He told me 25 years ago they were trying to take it from him and he would fight them forever,because the house was to be preserved. I’m reaching out to you because I must do this quietly. If you could connect me with anyone local who might know something about the history of this property I would be very grateful. Afraid to call Lawyers or town officials, not until I see what’s in the safe deposit box,etc. Assume any direct inquirys would be a mistake.Would like to speak with Historian Richard L.Porter if you know how to reach him. My Brother mentioned his name long ago and I believe he was a resident of Hopewell. Thanks