I have recently finished reading a book titled Elizabeth Haddon Estaugh, 1680-1762, Building the Quaker Community of Haddonfield, New Jersey, 1701-1762, by Jeffery M. Dorwart and Elizabeth A. Lyons.

It is an excellent book, and I highly recommend it for anyone interested in the life of one of West New Jersey’s early settlers—a young woman who came to the Province on her own in 1701.

I am not the only one intrigued by her history. The people of Haddonfield in Camden County, where Elizabeth lived, have extolled her virtues for many years, sometimes to excess, wandering into the realm of legend. Thankfully, the authors of Elizabeth Haddon Estaugh have relied on careful documentary research to give us a true history of Elizabeth’s life, along with that of her father John Haddon and her husband John Estaugh.

It is not easy to gather information on the lives of New Jersey’s proprietors, especially the ones who remained in England, as John Haddon did. Sources are not easy to come by. The authors have succeeded in giving us the history of a real family, not a mythical one

My focus here will not be on the history of Haddonfield, but rather on a large proprietary tract that was surveyed for Elizabeth’s father, John Haddon, in 1712. It was located in Amwell Township, Hunterdon County. Although the survey was made in John Haddon’s name, it was Elizabeth who applied for the survey on her father’s behalf, and Elizabeth and her husband who managed the property.1

The Haddons of England

John Haddon, born in Northamptonshire in 1653, became a member of the Quaker religion at a fairly young age, probably about the time his parents converted. At one point his father was imprisoned for attending a Quaker meeting. Being a Quaker in the late 17th century was not easy, as the Stuart monarchs saw these rabble rousers as a threat, and did all they could to make their lives difficult.

Sometime after 1670, John Haddon moved to London where he became a blacksmith. In a fairly short time, he established an iron foundry in the neighborhood of Bermondsey where he specialized in making ships’ anchors. That is where his daughter Elizabeth was born in 1680.

During this time, Quakers continued to be persecuted by the Stuart government. Vandalism and repressive fines were a big problem. Despite these troubles, Haddon’s business did well, and he benefitted from many business contacts who were not Quakers. He even got a contract from the Royal Treasury to mint coins to pay for military endeavors, which shows that he was not so doctrinaire that he would miss a good business opportunity.

Meanwhile, William Penn and other Quakers had set up a system for investing in the Province of West New Jersey. It required purchasing one of 100 proprietary shares, or a fraction of one. John Haddon’s Quaker friends encouraged him to invest, and he began to do so in the 1690s. Between 1698 and 1700, when dividends of land were made available to proprietors, Haddon was able to have properties surveyed in Gloucester County. Haddon was especially interested in locations that might prove advantageous for mining operations, since that was his line of work.

Because of the complexity of the land system, some properties were accidentally surveyed to more than one owner. Sometimes surveys were made so carelessly that boundary lines overlapped. This was the case with some of Haddon’s properties. He realized that he needed someone on the scene in West New Jersey to negotiate satisfactory solutions to these problems. But because of his many business commitments in England, as well as his age and concern for his health, he could not do this himself without a great deal of disruption and risk.

Instead, he sent his 20-year-old daughter Elizabeth to act as his agent. This was remarkable, not only because of her youth but because Elizabeth was a single woman.

Elizabeth Haddon

Elizabeth Haddon’s mother (also named Elizabeth) was very involved in her Quaker community. She was active in Quaker meetings and served on committees to help the poor and the persecuted. This no doubt set an important example for her daughters, who were educated to read and to write, and raised in an environment that promoted the ideal of equality for women.

Elizabeth was not only well-educated, she was devoted to her father and became interested in his business matters. She must have been both precocious and reliable. If not, her father would never have chosen her to represent his interests in West New Jersey. She made the trip to America on her own in 1701, and brought with her a power of attorney to act as father’s general agent.

While Elizabeth Haddon was still living in London she had become a devoted follower of a Quaker minister named John Estaugh. Estaugh come to America soon after Elizabeth did, and in 1702, they were married. The ceremony was attended by many prominent Quakers, including Samuel Jennings.2

John and Elizabeth Estaugh were quite busy setting up their home in Gloucester County as well as sorting out John Haddon’s real estate investments. They did not limit themselves to resolving disputes; they also applied for surveys in John Haddon’s name whenever the opportunity arose.

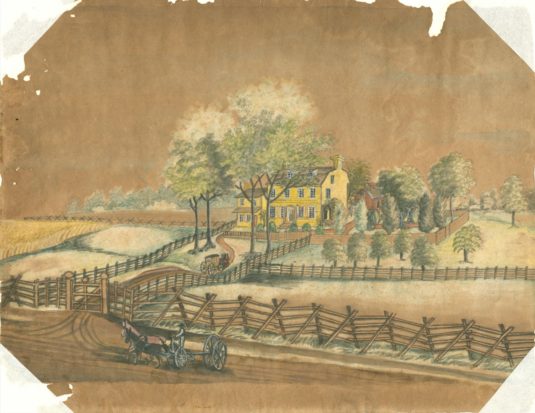

Addendum: Recently (August 2018) I found a beautiful picture of the Haddon-Estaugh house in Haddonfield, known as Haddon Hall, posted on Facebook by Margaret Westfield. Here it is:

The Haddon Tract in Amwell Township

I mentioned above that John Haddon had purchased several proprietary shares in West New Jersey. The proprietary system was rather complicated.3 The first step in converting shares into actual real estate was for the Board of Proprietors to purchase rights from the resident Indians to hundreds of thousands of acres. One such tract was the Lotting Purchase which was negotiated in 1703, consisting of 150,000 acres.4 The southernmost part of the Purchase covered the northern section of Amwell Township, which was established in 1708.

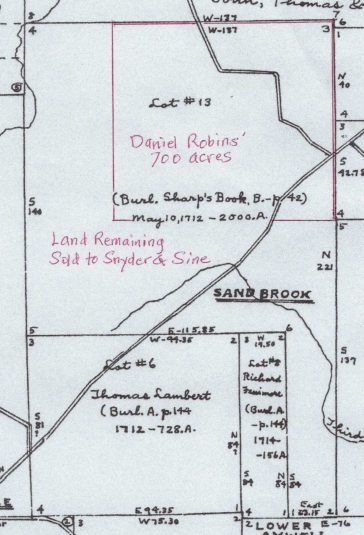

But it was not until 1712 that land in the Lotting Purchase was made available for surveys. Because of John Haddon’s proprietary rights, he was entitled to a 2,000-acre tract, and Elizabeth was able to get a survey made that very year. The survey for the Amwell Haddon tract was recorded on May 10, 1712 in Burlington, Sharp’s Book B p. 42.

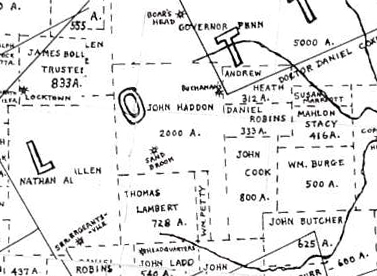

It bordered a 5000-acre property surveyed for the Penn family to the north, the large tract of land owned by Nathan Allen on the west, and smaller tracts on the south and east belonging to Thomas Lambert, Richard Fenimore, John Cook, Daniel Robins and Andrew Heath. Its eastern border passed through the intersection of today’s Routes 523 and 579.5

Just one year later, John Haddon wrote to Elizabeth that she should sell some of his properties in order to make herself and her family more comfortable, and also to help him with his growing debts. This was not always easy, since some of the boundaries of their properties were still in dispute. The Estaughs did manage to sell some real estate, but despite the urgency that John Haddon was feeling about his need for cash, the Amwell Township tract was retained for another ten years. The first sale did not take place until around 1725, two years after John Haddon’s death.

This sale was made to Daniel Robins for 700 acres. The rest of the tract remained in the hands of the Haddon estate until twenty years later, and six years after the death of Elizabeth’s husband John Estaugh in 1742. In 1748, Elizabeth Haddon Estaugh sold the balance of 1300 acres to two German immigrants, Jacob Peter Sniter and Nicholas Syne for £780.6

Elizabeth Haddon Estaugh died in 1762, at the age of 77, having done much to support her Quaker community and the neighborhood of Haddonfield, in addition to assuming the burden of administering her father’s properties. She was much lamented by her community.

The Haddon Tract Divided

As mentioned above, the first purchaser from Elizabeth Haddon, as agent for her father John Haddon, was Daniel Robins. I have written about him, his families and his property at some length.

Snyder & Sine

At the time of the purchase in 1748, Johann Peter ‘Sniter’ and Nicholas ‘Sayn’ were both residents of Amwell Township and in “actual possession” of the property. After the sale, they held it as “Tenants in Common.” There is no way to know for certain when the two men and their families took up residence on the Haddon tract, but it was almost certainly well before they made their purchase.

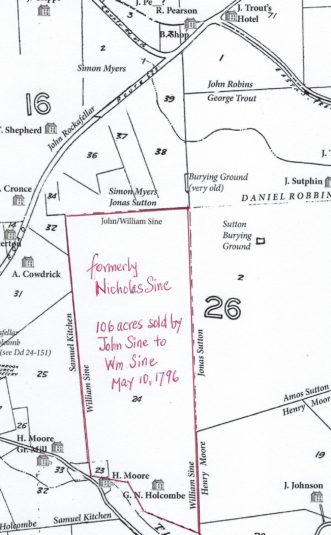

One year after the purchase, Nicholas Sine and Jacob Snyder divided their share of the Haddon tract between them. We know this from a later deed on file at the Hunterdon County Historical Society, made on May 10, 1796.7

According to this deed Snyder and Sine had lost no time in disposing of a large portion of their 1300 acres. The recital given in the 1796 deed explained that after selling off “Several Parcells of land,” the two men were left with 532 acres, meaning they had sold off about 768 acres. Once Snyder and Sine had divided the land remaining between them, each was left with 266 acres.

I wish I could draw the dividing line between Snyder and Sine, but I do not yet have enough information about the later owners. In this article, I will focus on the property that went to Nicholas Sine.

Nicholas Sine

Nicholas Sayn/Sine (also known as Nickolas Signe) was present in New York by 1724 when he married Urseltje Maul at the Dutch Reformed Church there. Sine was naturalized on July 8, 1730, along with many other German immigrants who later settled in Amwell Township in Hunterdon County: Godfrey Peters, Hendrick Bost, Johann Willem Snoek, Jacob Moore, Rudolph Herley, Anthony Habback, John Moore, Jacob Houselt, Hendrick Dirdorf, Johan Peter Rockefelter and his sons Peter and Johannes, Peter Bodine, Anthony Dirdorf and his four sons.8 One wonders if they all traveled as a group from New York to Amwell. Jacob Moore, Rudolph Herley [Harley] and Anthony Dirdorf were members of the Amwell Church of the Brethren which was established in Amwell in 1733. Sine might also have been, although records of church membership in its earliest years have not survived.

Nicholas Sine wrote his will on November 7, 1778. He did not name his wife, so she probably predeceased him. To his son William he left £5 as a birthright. To his daughters Elizabeth Bartholomew and Ann Sine, he left £5 each. He must have previously provided for all three of them in some significant way because he left the residue of his estate to his “cousin” John Sine. Another departure from the norm was to name as his executors not his son William but his “friends” John Lambert and Peter Rockafellow Jr., both of them also early settlers in Amwell Township. The will was witnessed by John Lake, William Taylor, and Barnet VanZandt.

Who was this “cousin” John Sine? Nicholas was the son of Conrad Sine and brother of Conrad Jr. According to H. Z. Jones,9 Conrad Jr. and wife Elizabetha Christina Sine had eight children, one of them being Honis (John) Sine, who was christened at Tarrytown, NY in 1727. Thus, John was actually Nicholas Sine’s nephew, in our modern terminology. In the 18th century, people used the word “cousin” far more loosely than we do.

Nicholas Sine survived another three years after writing his will, which was not recorded until September 19, 1781. After his death, property once owned by him was still identified as his. For instance, in 1787 Nicholas Sine bordered Isaac Rounsavel (the Cook tract). In 1795 he bordered land of Philip Calvin dec’d. The explanation for this is that these property descriptions were taken literally from older descriptions. It was pretty common to lift the description exactly from an earlier deed without bothering to update the names of bordering owners.

As for Philip Calvin I was at first surprised that he owned land bordering Nicholas Sine. I knew that he owned land at Prallsville as well as along Route 523 closer to Stockton. There is no deed recorded for his land in or near the Haddon tract, but in 1795, Philip Calvin’s executors gave a mortgage to Simeon & Elizabeth Myers, purchasers of 134.75 acres from Calvin’s estate, and the mortgage named the bordering owners as Andrew Bearder, John Rockafellow, John Sine, John Buchannon, John Robins, road from Buchanan’s to Howell’s Ferry.10 Note that one of the borders was John Sine.

The Deed of 1796

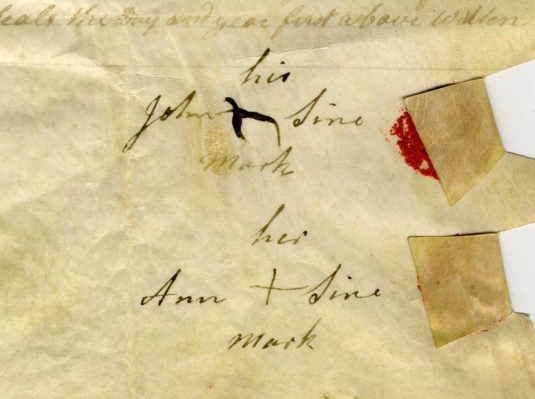

As mentioned earlier, on May 10, 1796, John Sine and wife Anna (or Ann) conveyed to their son William Sine a tract of 106 acres in exchange for £260.11 This is a lovely manuscript deed, written on parchment, so it is likely to survive intact for decades (if not centuries) to come.

Since the division between Nicholas Sine and Jacob Snyder gave each man a tract of about 266 acres, and Nicholas Sine had bequeathed his real estate to nephew John Sine, it appears that John Sine must have disposed of about 160 acres, unless that is, Nicholas Sine had disposed of some lots before writing his will in 1778. Quite possibly some of the property went to sons William and Peter.

By plotting the 1796 deed, we get a clue as to where Nicholas Sine’s half of the remaining property was located.

John Sine, Sr. of Amwell wrote his will on January 23, 1797. He provided for his wife Anna by leaving her a horse, a cow and a room in his house with its furniture. Sons William and Peter had already received their shares, and to son John (Jr.) he left his home plantation, with the proviso that he pay the estate £230 and provide for his mother during her life. He left monetary bequests to daughters Eve Fox, Elizabeth Sine and Susanna Sine. He also left bequests to grandchildren Anna Whilton and John Lake.

For more about this property, see The Sine Farm.

Correction:

I incorrectly identified the children of John Sine as those of his son William. And the William Sine who was John Sine’s son did not marry Catharine Hoagland or Sarah Kyple. The William Sine who married Caty Hoagland on December 9, 1804 was the son of Nicholas Sine and Mary Smith, and lived from about 1781 to 1860. The William Sine who married Sarah Kyple on April 15, 1807 was probably William Sine, Jr., the son of William and Mary Sine, and lived from about 1797 to 1858.

John and Anna Sine had three sons and three daughters. The sons were William, whose wife was Mary, surname not known; Peter probably died unmarried; and John, whose wife was Elizabeth, surname not known. The daughters were Christine, married a Mr. Whilton; Catharine, married Garret Rittenhouse; and Eve, married Jacob Fox.

In 1805, John Sine, Jr., son of John (Honis) and Anna Sine, sold his father’s plantation, it being “all the lands where said John Sine now lives.” The purchaser was Maj. George N. Holcombe (1747-1811), who, at the same time, sold to John Sine a lot of 16.7 acres where the Boarshead Tavern stood.12

Sine did commence operation of the tavern because in 1806, the year he died, the tavern was identified as “John Sine’s Tavern.”13 If I have the right John Sine, he was 72 years old when he died, a little ancient to be running a tavern. He died without writing a will, despite a sizable inventory of $1,016.27. Administrators of the estate were James Gregg and John Robbins. We will leave him here because he was no longer a resident of the old Haddon tract.

George Holcombe sold the Sine lot in the Haddon tract to his nephew Solomon Holcombe (1789-1871) the next year (1806).14

For the next post I will track one of the properties that had belonged to Nicholas Sine’s partner, Jacob Peter Snyder.

Addendum: I only realized this after publication, but I had previously written about Nicholas Sine in this article. I’ve been publishing since 2009, and it’s getting hard to remember what I’ve done in the past.

Footnotes:

- I had debated categorizing this article as “In My Library,” but realized it really belongs with other articles I have written about proprietary owners and early settlers of Hunterdon County. ↩

- I wrote a little about Samuel Jennings in my previous post, “Who Was the Artist?” ↩

- I wrote about how it works in “How New Jersey Began.” ↩

- For more on the Lotting Purchase, see John Reading and the Creation of Hunterdon County, part two. ↩

- I have written about Daniel Robins and his property in several articles, which are listed under “Buchanan’s Tavern” under Topics in the right-hand column. ↩

- West Jersey Proprietors’ Deeds, Book HH fol. 37. ↩

- Recital in Hunterdon County Historical Society, Ms. Deeds, Coll. 18, part I, folder 171. The deed was never recorded. ↩

- “Colonial Naturalization List, 1713-1772,” by Henry Race, M.D., The Jerseyman, vol. 2, no.1, March 1893, pp. 1-3. ↩

- Henry Z. Jones, More Palatine Families; Some Immigrants to the Middle Colonies 1717-1776 and their European Origins, Universal City, CA, 1991, pp. 271-72. ↩

- H.C. Mortgage Book 2 p. 117. ↩

- HCHS Coll. 18, part 1, folder 171. Many thanks to Robert Leith for scanning the deed and sending me a copy. ↩

- H. C. Deeds, Book 11 pp. 43, 45. See also “Boarshead Tavern” and “Boarshead Tavern in the 18th Century.” ↩

- H. C. Deed Book 15 p.91. ↩

- H. C. Deed Book 25 p. 87. ↩

Marshall Lake

November 11, 2017 @ 2:47 pm

Marfy,

The article names John LAKE as a grandson of John SINE (LWT 1797). Do you know which one of John SINE’s daughters married a LAKE and which LAKE she married? If not, do you know who this John LAKE (the grandson) might be?

Marshall

Marfy Goodspeed

November 11, 2017 @ 7:58 pm

Marshall, I’m afraid I do not know who this John Lake was. I’ve got eight John Lakes in my database who would be the right age to be John Sine’s grandson, but only two who’s mother is not identified. She would have to be a Sine. John Sine had five daughters. There are two of them who have not yet had husbands identified, Elizabeth and Susanna, who were not yet married when John Sine wrote his will in 1797. Perhaps this will give you a clue for some research.

Marfy Goodspeed

November 12, 2017 @ 6:24 am

Marshall, Apologies for the previous reply. John Sine’s two unmarried daughters obviously could not be the mothers of John lake, since Sine’s will had identified Lake as his grandson. Sine’s other three daughters, named in his will, were Catharine, wife of Garret Rittenhouse; Eve Fox (wife of Jacob Fox, and later of Thomas Godown; and Christine Whilton (who was dec’d, and had a daughter Anna). The only explanation I can think of is that there was a sixth daughter who had married a Lake and died before 1795 when Sine wrote his will. A possibility might be John Lake, born 25 Feb 1776, died 3 May 1849, and buried in the Lower Amwell Old Yard, parents not identified. Another might be John C. Lake, born 14 April 1776 in Kingwood, died 1854 in Bethlehem Twp., but because he was so strongly identified with Bethlehem Twp., I rather doubt he was Sine’s grandson. The first mentioned John Lake looks like a good candidate.

Marshall Lake

November 12, 2017 @ 11:37 am

Thanks for following up, Marfy.

John C LAKE (1776-1854) has been identified as a son of Abraham LAKE (d 1796) and Elizabeth —— (d 1839).

John LAKE (1776-1849) has, as far as I can tell, been identified as the

last-born child of John LAKE (1728-1809) and [presumably] Sarah Ann ROBINS (1736-1823).

I wonder if grandson John LAKE named in John SINE’s will is an illegitimate child? The mother of John LAKE is not named in the will (even though the mother of grandaughter Anna is named). Additionally, there were several cases of various LAKEs having illegitimate children in Amwell & Bethlehem Twps in this time frame. It may have been an epidemic. :)

Marfy Goodspeed

November 12, 2017 @ 5:19 pm

That seems like the most likely explanation. Makes life tough for genealogists.