On November 16, I gave a speech about John Reading and the Creation of Hunterdon County. There was quite a lot of information in that speech, covering the years 1664 to 1718. In fact, it was probably a bit too much.

For example, the beginning of the speech covered the conquest of New Netherland by the English in 1664, the Third Anglo-Dutch War of 1672-74, the Quintipartite Deed of 1676, and John Reading’s settlement in Gloucester County in 1684; also Edward Byllinge and the early settlement of West New Jersey. Rather than rehash material that I have already written about, you can see a list of pertinent articles at the end of this one. They cover the settlement of West New Jersey, its political history, its infamous governor Daniel Coxe, and the early career of John Reading.

For the history of Hunterdon County, it is best to start with 1694. What follows is the first part of a somewhat amended version of the speech.

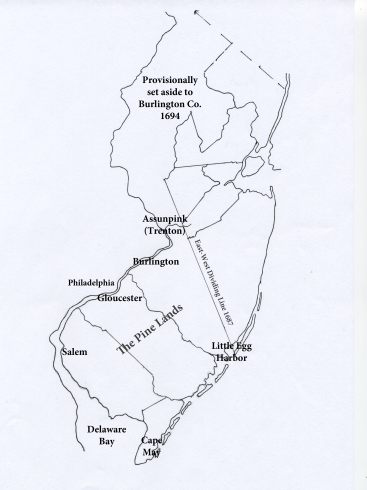

Burlington County in 1694

Hunterdon began as part of Burlington County. At first, Burlington’s original boundaries were only approximated. In 1694, they were officially established, a full 17 years after the county was first settled. The “northern boundary” was to be the Assunpink Creek at Trenton, but everything north of that was also claimed by the Burlington Court.

The law of 1694 stated that “all Persons inhabiting in this province above the river Derwent (being the Northern Boundary of the County of Burlington) shall belong and be Subject to the Jurisdiction of the Court of Burlington, until further Order of the General Assembly.” Derwent was a temporary name for Assunpink Creek (apparently a common name for a river in England).

Was Burlington just being greedy? No—the lands from Trenton north were already being settled without the benefit of government. This can lead to all sorts of problems, especially when people want the services of a constable or to have their roads maintained or to sue for redress of grievances. This law gave them access to the minimal government services available in 1694.1

The Unification of the Jerseys

In 1702, the proprietors of East and West New Jersey surrendered their rights of self-government. As far as England was concerned, the two Jerseys never had the right of government in the first place, but the two colonies insisted they did, and would have tried to keep it, but things had gotten out of their control. John E. Pomfret covers this period well in his book Colonial New Jersey, A History.2

Pressure from England for consolidation began as soon as James came to the throne in 1685. And in New Jersey, plans had been in the works as early as the late 1690s. In January 1702 a final draft of the terms of surrender was sent by the Board of Trade to the king, who was at this time William III. But William died on March 8, 1702, at which time his wife’s sister, Anne, became Queen (she was not crowned until April 23, 1702).

The surrender was accepted by the Queen on April 17, 1702, but it took time for news to get back to New Jersey. As clerk of the Gloucester Court, John Reading wrote in the minute book on June 1, 1703: “Here ends the Proprietary Government of the Province of West New Jersey.” 3

Since both East and West New Jersey agreed to the surrender, the Queen’s officers took the opportunity to unite the two into one royal province. From then on, the governor of the colony would be named by the Crown. Previously the governor of West New Jersey was the person who owned the most proprietary shares, first, Edward Byllinge, followed by Daniel Coxe, Sr. Then came Jeremiah Basse and Andrew Hamilton.

Coxe wanted the position of Governor so that he could more easily acquire property in the colony, and make sure no legislation would be passed by the West Jersey Assembly that might hinder his goals. He had an enormous appetite for land in the British colonies, and did a good job of satisfying that appetite. He also had a son named Daniel Coxe Jr. who was just as voracious, and who will play an important role in this story.

The Fundamental Laws & the Governor’s Instructions

Prior to the unification, a sort of constitution was relied on by the Quakers, generally known as the Fundamental Laws of West New Jersey, passed by the Assembly in 1681. It is a remarkable document with a list of rights and restrictions that could serve as a model for modern democracies. It was notable for how much power it gave to the Assembly and denied to the Governor. It is rarely given its due, probably because it was only in effect for about 20 years.

When West New Jersey became part of a royal colony, the Fundamental Laws were replaced by The Governor’s Instructions, issued by the Crown whenever a royal governor was appointed.4

Among other things, the Instructions of 1702 stated that from now on the Assembly would meet alternately at Perth Amboy, the once capital of East New Jersey, and at Burlington, capital of West New Jersey. It was as if the proprietors of New Jersey were willing to give up their right of government, but not willing to give up their identity as two separate places, even though now there was only one Assembly to represent them both. Travel challenges also had a role to play in this.

Getting from Gloucester to Hunterdon

Following unification of the two Jerseys, proprietors began casting their eyes toward the fertile lands north of the falls of the Delaware at Trenton. I have often pondered how John Reading and other early explorers and surveyors made their way into Hunterdon County. There were no roads back then—just an impenetrable forest.

This is not something that can be easily seen today, thanks to browsing deer and invasive plants that discourage the growth of understory bushes and sapling trees. There is such a place in Delaware Township—a 16-acre plot owned by William T. Wyman, fenced off from the deer, and carefully tended to encourage natural forest growth. A visitor quickly discovers how impenetrable those early forests were, and how difficult it must have been for travelers, even those on horseback, to make their way.

To travel north from Gloucester, there was the river, and a very few Indian paths. But the river was impractical in many ways, so surveyors of those days always traveled by horseback. That being the case, how did Reading get north to Hunterdon? Here are some possible routes:

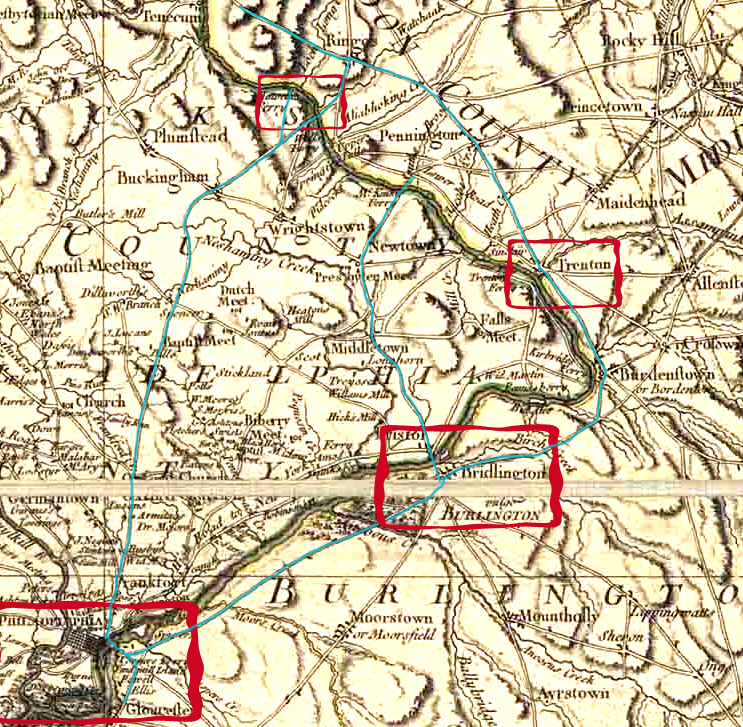

1) He could have taken the path that connected Gloucester City with Burlington City, and then continued on to Stacey’s Mill on the Assunpink (at Trenton). From there he could take an established Indian path called the Malayaleck Path that is today’s Route 579, which ran all the way north to Easton, PA. North of Trenton, the path ran inland. As the map shows, this was the longest route, and probably not the preferred one.

2) Or, he could have gone to Burlington, and then crossed the river at Bristol and taken a path that ran north through Pennsylvania to Newtown and then northeast to the river where he might have crossed at Washington’s Crossing, and then made his way north from there, again along the Malayaleck Path.

3) Finally, he could have crossed the river at Gloucester (there was a ferry there), traveled to Philadelphia where he could pick up another old Indian path that eventually became known as the Old York Road. This path ran northeast to today’s Stockton. It was laid out as a public road in 1711.

Reading may have used all three routes at one time or another. But usually he had to take a route that got him to Burlington, because that is where surveys had to be recorded.

The Indian Purchases

It was established policy among the Quakers to purchase land from the Indians on behalf of all the settlers before surveying lots for individuals. This was a strategy to help protect the Quakers from challenges to their legitimacy. The Quakers didn’t want to create any excuse for the government in England to deprive them of their hard-earned rights in West New Jersey.

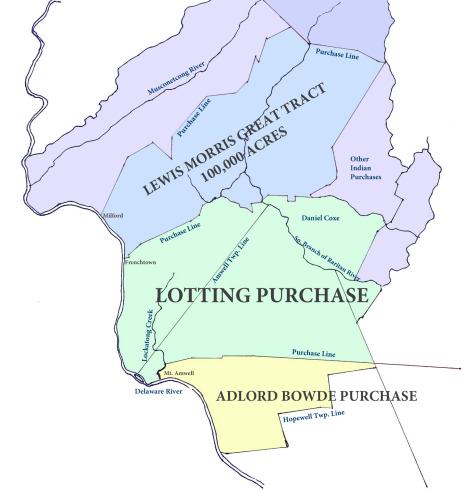

The first of the major land purchases in what became the original Hunterdon County was 15,000 acres bought by Thomas Budd in 1687. This area ran from Millstone to Lawrenceville to the area north of Trenton.5

Next came the purchase of a huge tract of land made in 1688 by Adlord Bowde, agent for Daniel Coxe (who, prior to 1692, owned rights to more of West New Jersey than anyone else). The tract was about 30,000 acres, and bordered ‘the road to New York, Shabbicunk Creek, land of Thomas Budd, and “Laocolon Creek.” Laocolon was one of the many variant spellings of the Lockatong Creek. This purchase included all of today’s Hopewell Township, most of the Amwells and the southern part of Delaware Township.6

Bowde bought the land from the Indian sachems Hoham, Teptaopamun and other “Sackimackers” or Sachems. Hoham may very well have been Himhammoe, whose name will come up again shortly. These were actually members of the Indian group known as Sanhikans, who generally lived in and around Trenton.

The Lotting Purchase

The third and largest Indian purchase took place in 1703, after unification of East & West New Jersey, and was known as the Lotting Purchase (‘lot’ meaning a share rather than a measured piece of land). It amounted to 150,000 acres, and, based on Hammond’s map, it ran from the northern line of the Bowde purchase, up to a line that ran from Frenchtown to Pittstown, then following the Capoolong Creek to the South Branch of the Raritan, then down that to its meeting with the North Branch, not far from Neshanic.

John Reading was one of the three men named to negotiate with Indian leaders for the Lotting Purchase. There were only two sachems named, Caponockonikon and Himhammoe, an indication that the Indian population in this part of New Jersey had shrunk by that time. Normally you would get several Indians signing a deed like this. Most likely causes of the decline were epidemics of malaria and smallpox that had been spreading through the Indian populations in New Jersey and New York.

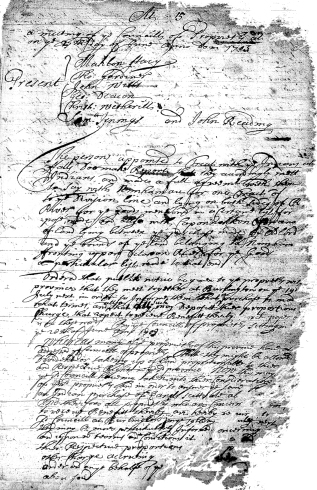

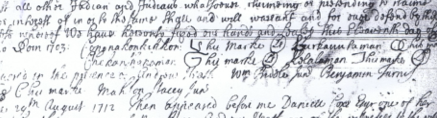

Detail of the deed signed with Caponokonickon and three other sachems, each of them by mark. The other two were Lurkanlaman?, Chekanhanaman? and Holalaman. The deed was signed in 1703 but not recorded until 1712.7

Back in 1687 when Thomas Budd made his purchase, there were 10 sachems signing the deed, suggesting a population of about 150-200 people. Three years later, in the sale to Adlord Bowde, there were 6 sachems. But by 1703, when 150,000 acres in Hunterdon County were sold, only two sachems acted as grantors: Caponokonickon and Himhamoe.8

The negotiating committee reported to the Council of Proprietors on June 27, 1703 “that they had made a full agreement with Himhammoe for one tract of land adjoining to the division line” (i.e., the line between East and West New Jersey) “and lying on both sides of the Raritan River. And also with Coponnockous for another tract of land, lying between the purchase made by Adlord Bowde and the boundaries of the land belonging to Himhammoe fronting on the Delaware.”9

At another meeting of the Council, held on November 2, 1703, the same committee was sent to those Indians, particularly to “Coponnockous,” to have the tract of land lately purchased “marked forth, and get them to sign a deed for the same, . . . and that they go to Himhammoe’s wigwam in order to treat with them, and to see the bounds of the land lately purchased of him.”

After the Lotting Purchase was made in 1703, the proprietors discovered they could not go ahead and issue dividends as they had intended, because they did not have enough acreage to allow them to issue 5,000 acres for each proprietary share. They needed more land, which they got in 1709. This was another tract of 100,000 acres bought from the Indians by Lewis Morris, running north from the Lotting Purchase Line—from Frenchtown up the river to the vicinity of Milford, then northeast to the northern boundary of Lebanon Township, covering almost all of northern Hunterdon as we know it today. This became somewhat controversial when Morris claimed this new land was meant for the West Jersey Society, a consortium of proprietors who had purchased the shares of Daniel Coxe. The West Jersey Proprietors did not agree, which helped to delay matters. Later purchases covered the Musconetcong Creek on both sides.

Also in 1709, there were some Indian purchases made on the northeast end of today’s Hunterdon. They were not authorized by the West Jersey Proprietors. One of them was the Willocks tract of 18,000 acres, another the Kirkbride tract. They had been given licenses to purchase Indian lands by the corrupt Governor Ingoldsby. The West Jersey Proprietors had to force these two men back into the proprietary system. Willocks, at least, managed to buy a proprietary share in West New Jersey, that gave him rights to his purchase, but he still had to get clearance from the Council of Proprietors.

There were political reasons why it took six more years to get the second Indian purchase made, and even then, the proprietors had to wait before recording their surveys. The earliest surveys in the Lotting Purchase did not get recorded until 1712.

Surveys in the Bowde Purchase

However, this was not the case for land in the Adlord Bowde Purchase. Settlement was happening there in the 1690s, and townships followed. Maidenhead (now Lawrence) Township was created in 1697, and Hopewell Township in January 1699/1700. But that area that can be seen north of the Hopewell Township boundary and south of the Lotting Purchase line (the yellow shaded area) was in a sort of limbo. It was unincorporated as a municipality, yet it was available for surveys.

The earliest survey in that area was made in 1695 for John Calow’s land along the Delaware River just north of Lambertville. More surveys were made in the late 1690s and early 1700s, including some for John Reading. Some of the surveys extended beyond the purchase line into what was then unpurchased lands. I do not know how they got away with that. But one of them was made for Arant Sonman’s, who was a crony of Gov. Cornbury and notoriously corrupt. Perhaps that explains it.

Whatever route that Reading took north from Gloucester, he was well-acquainted with the terrain that was outlined in the Lotting Purchase. He probably took a close look at the area on the western boundary with the Adlord Bowde Purchase, which was the Lockatong Creek, because in 1704 he had a tract of 1440 acres surveyed next to that boundary. 10

Next article: John Reading’s plantation; creation of Amwell Township; Gov. Cornbury and his cronies. See Creation of Hunterdon County, part two.

Articles on the History of West New Jersey

For continuation of this story, see John Reading, part two.

I have not published articles about West New Jersey since March 2011, but hope to continue the story next year. The years 1692 through 1702 were very eventful for the Province.

- How New Jersey Began

- West New Jersey, 1674-1680

- Postscript to WNJ

- West New Jersey – 1680

- West New Jersey in 1681

- West New Jersey, 1682

- West New Jersey, 1683

- West New Jersey, 1684

- West New Jersey, 1685

- West New Jersey, 1686

- West New Jersey in 1687, Part One

- West New Jersey in 1687, Part Two

- East New Jersey, West New Jersey

- Proprietary Land Titles

- West New Jersey, 1688

Daniel Coxe figures in the story, and even more so, his son Daniel Coxe Jr. I wrote several articles about Daniel Coxe Sr., finding him to be a most intriguing fellow:

- Daniel Coxe, Part 1

- More on the Curious Dr. Daniel Coxe

- Daniel Coxe, Physician

- The “Inquisitive” Dr. Coxe

- The “Learned and Intelligent Dr. Daniel Coxe”

- The Radical Daniel Coxe

- Coxe and the Colonies, Part One

- The Carolina Constitutions

- Daniel Coxe, Merchant Investor

Then I continued with the saga of the Province of West New Jersey:

- West NJ 1688 and Daniel Coxe part one

- 1688, Daniel Coxe’s Schemes

- Coxe’s Landholdings, 1688

- The Missing Records

- The Great Seal of West Jersey

- West New Jersey 1689, part one

- West New Jersey, 1689 part two

- West New Jersey 1690, part one

- West New Jersey 1690, part two

- West New Jersey 1691

This article focused on John Reading: John Reading and the Town of Gloucester, 1686 (12/31/2009)

Footnotes:

- For more background on the early history of the Trenton area, see A History of Trenton, 1679-1929, 250 Years of a Notable Town with Links in Four Centuries, by Edwin Robert Walker; Chapter One, The Colonial Period. Also see Dr. Hall’s History of the Presbyterian Church at Trenton, and Raum’s History of Trenton. ↩

- Scribners, 1973. ↩

- Frank H. Stewart, comp., Gloucester County Under the Proprietors, reprinted from “The Constitution,” April 9, 1941 to November 26, 1941, Gloucester County Historical Society, 2000, p. 18. ↩

- The Laws can be seen in The Grants and Concessions of NJ, by Aaron Leaming and Jacob Spicer, first published in 1752, as well as the Governor’s Instructions for Lord Cornbury. ↩

- I discussed this sale in my article, West NJ in 1687, part two. ↩

- I discussed the Bowde purchase here. ↩

- NJ State Archives, Deed Book AAA fol. 435. ↩

- I regret to say I did not footnote the source for this information in my notes of a few years ago, but it most likely came from Richard S. Grumet. ↩

- From Smith’s History pp. 95-97, and Snell 1881, p. 182. ↩

- N. J. State Archives, West Jersey Proprietors, Basse Survey Book, p. 86, and Survey Book A p. 143. West Jersey Proprietors (hereafter WJP). State Archives are hereafter NJSA. ↩

Stephen Shafer

November 22, 2014 @ 8:17 am

Terrific work! Thank you so much.

Sandra Miranda

December 11, 2020 @ 12:15 pm

Just wanted to add something about the “New Jersey Society” and the Survey of Paulinskill Meadows that everyone seems to think Samuel Green surveyed.

“New Jersey Society” was formed in 1692 by forty eight Londoners that became shareholders in a join stock company founded to purchase the American holding of Dr. Daniel Coxe. From Coxe, the new organization acquired some twenty proprietary shares in the province of West Jersey, two and a half shares in East Jersey and 10,000 acres in Pennsylvania. Also Coxe conveyed his claim to the sole right of government in West Jersey. Supervision of the Society business was entrusted to a thirteen man committee, elected by al shareholders at a annual meeting..Dr. Coxe who controlled the company was an adherent of the English Church and not over friendly to Quakers.

On April 17 1702, New Jersey was transformed into the crown colony and the proprietors were allowed to retain their land rights

In 1713 the West Jersey Council of Proprietors purchased all of the land above the the fall of the Delaware (Trenton) from Native Americans

In 1715, Thomas Stevenson and John Reading Jr. surveyed the land that is now Warren county. From 1713 to 1738 Warren county was part of Hunterdon County. From 1738 to 1753 it was part of Morris County and then until its formation in 1824 it was part of Sussex County.

John Reading Jr. served as governor of the British Province of New Jersey in 1747 and again from September 1757 to June 1758.

Reading managed the landed interests for the family of William Penn. It was John Reading Jr who surveyed the land and then sold it to William Penn.

William Penn acquired the land in 1715, which came into the ownership of Penn’s sons in 1760. Reading’s report and subsequent books by various writers on Indian habitations and caves in Sussex County suggests that the Paulinskill Meadows was used and resided on by the Native Americans.