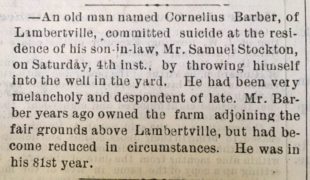

Cornelius H. Barber

Sometimes in my researches on Hunterdon people of the past, odd things turn up. Something very odd turned up when I came across Cornelius H. Barber, who lived from 1804 to 1884. I had been asked about the Prall tanyard, which was located a short distance south of Sergeantsville in the early 1800s, and discovered that Barber had briefly been an owner.

So let me tell you a little about Cornelius Hoppock Barber before describing the odd thing I found.